Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 March 2026, 8:04 AM

Unit 3: Anatomy of a CC licence

Introduction

Creative Commons licences give everyone from individual creators to large companies and institutions a clear, standardised way to grant permission to others to use their creative work. From the reuser’s perspective, the presence of a Creative Commons licence answers the question, ‘What can I do with this?’ and provides freedom to reuse, subject to clearly defined conditions.

All Creative Commons licences ensure that creators retain their copyright and get credit for their work, while permitting others to copy and distribute it. Although the tools are designed to be as easy to use as possible, there are still some things to learn in order to fully understand their mechanics.

This unit has four sections:

- 3.1 Licence design and terminology

- 3.2 Licence scope

- 3.3 Licence types

- 3.4 Licence enforceability

There are also additional resources if you are interested in learning more about any of the topics covered in this unit.

3.1 Licence design and terminology

This section covers the acronyms, terms and symbols used in connection with Creative Commons’ tools. We will also review important features of how the licences were designed.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- distinguish different CC licences

- identify the three layers of CC licences.

Reflection

Thinking back to the material covered in Units 1 and 2, why might resources with a CC licence be useful? How could CC-licensed resources benefit your university or college?

Introduction

Given that most of us are not lawyers, what do we need to know about the legalities in order to use Creative Commons licences properly?

Creative Commons’ legal tools were designed to be as accessible to everyone as possible while still being legally robust. CC’s founders made several design decisions that make these legal tools relatively easy to use and understand.

As we saw in Unit 1, copyright operates by default under an ‘all rights reserved’ approach. Creative Commons licences function within copyright law, but they utilise a ‘some rights reserved’ approach. While there are several different CC licence options, all of them grant the public permission to use the works under certain standardised conditions. The licences grant those permissions for as long as the underlying copyright lasts or until you violate the licence terms. This is what we mean when we say CC licences work on top of copyright, not instead of copyright.

The licences were designed to be a free, voluntary solution for creators who want to grant the public up-front permissions to use their works. Although they are legally enforceable tools, they were designed in a way that was intended to make them accessible to non-lawyers.

Licence structure

The licences are built using a three-layer design.

Let’s look at the separate layers of a licence, as shown on the diagram above:

- The legal code is the base layer. This contains the ‘lawyer-readable’ terms and conditions that are legally enforceable in court.

- The human-readable commons deeds are the most well-known layer of the licences. These are the web pages that lay out the key licence terms in a way that is clear and easily understandable. The deeds are not legally enforceable but instead summarise the legal code.

- The final layer of the licence design recognises that software plays a critical role in creating, copying, discovering and distributing works. In order to make it easy for websites and web services to know when a work is available under a Creative Commons licence, Creative Commons provide a ‘machine readable’ version of the licence – a summary of the key freedoms granted and obligations imposed written into a format that applications, search engines, and other kinds of technology can understand. Creative Commons developed a standardised way to describe licences that software can understand called CC Rights Expression Language (CC REL) to accomplish this. When this metadata is attached to CC-licensed works, someone searching for a CC-licensed work using a search engine (such as Google’s advanced search) can more easily discover CC-licensed works.

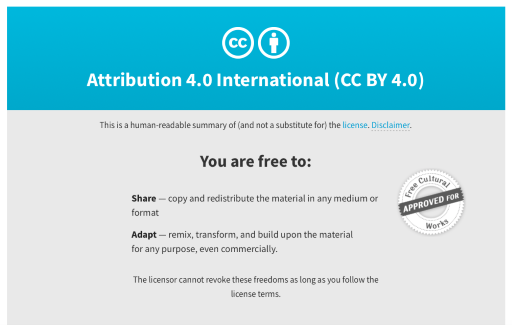

Let’s take a quick look at the CC BY 4.0 International licence to see where we can find different layers of the licence. This is the human-readable version of the licence:

As you can see before the list of permissions that the licence grants, it clearly states: ‘This is a human-readable summary of (and not a substitute for) the licence.’ If you were to click on this link, you would find the legal code that underpins this licence type.

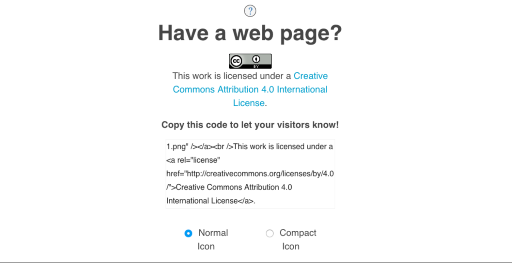

When you apply a CC licence to your own work, some platforms that host CC-licensed material (such as Flickr) will add machine-readable code to your work so it can be identified as openly licensed on their platform. If you have your own webpage, you can add a ‘machine-readable’ version of the licence that enables your work to be identified as using a CC licence by using the Creative Commons licence chooser. (We will discuss how to license your work in Units 4 and 5.)

CC licence basics

All Creative Commons licences have many important features in common:

- Every CC licence ensures licensors get credit for their work.

- CC licences work around the world.

- A CC licence lasts as long as applicable copyright lasts (because they are built on copyright) and as long as the user complies with the licence. Under the new Myanmar Copyright Act, most works are protected by copyright for 50 years after the creator’s death.

- At a minimum, every licence helps creators (called ‘licensors’ when they use CC tools) retain copyright while allowing others to copy and distribute their work in unadapted form for non-commercial purposes. The common features of each licence serve as the baseline, on top of which licensors can choose to grant additional permissions when deciding how they want their work to be used.

As you may have noticed in the earlier example, CC licences include a version number. At August 2020, the current version of the CC licences is 4.0. Throughout this course, please assume all descriptions of licences refer to this version of the CC licence suite, unless otherwise noted. (You will learn more about the different versions in Section 3.4.)

Choices for the licensor

All Creative Commons licences are structured to give the user permission to make a wide range of uses as long as the user complies with the conditions in the licence. The basic condition in all the licences is that the user provides credit to the licensor and certain other information, such as where the original work may be found.

A CC licensor makes a few simple decisions on the path to choosing a licence: ‘First, do I want to allow commercial use, and second, do I want to allow derivative works (also known as adaptations)?’ We’ll address how to do that in a later section.

If a licensor decides to allow derivative works, they may also choose to require that anyone who uses the work (called licensees)make their new work available under the same licence terms. This is what is meant by ‘ShareAlike’ and it is one of the mechanisms that helps the digital commons of CC-licensed content grow over time. ShareAlike is inspired by the GNU General Public Licence, used by many free and open source software projects.

These different licence elements are symbolised by visual icons:

| This symbol means Attribution,or ‘BY’. All of the licences include this condition. This is because you must attribute when you use any CC-licensed resource. Best practice for attribution means providing the title, author, source and licence. We will see some examples of how to attribute resources you use throughout the rest of the course. |

| This symbol means NonCommercial,or ‘NC’, which means the work is only available to be used for noncommercial purposes. This means you cannot profit or make money from the resource. Three of the CC licences include this restriction. |

| This symbol means ShareAlike,or ‘SA’, which means that adaptations based on this work must be licensed under the same licence. Two of the CC licences include this condition. |

| This symbol means NoDerivatives,or ‘ND’, which means reusers cannot make changes to the resource and share adaptations of the work. Two of the CC licences include this restriction. |

When combined, these icons represent the six CC licence options. The icons are also embedded in the ‘licence icons’, which each represent a particular CC licence type. Section 3.3 explores the combinations in detail.

Public domain tools

In addition to the CC licence suite, CC also has two public domain tools represented by the icons below. We met these tools briefly in Section 2.1. These public domain tools are not licences.

| CC0 enables creators to dedicate their works to the worldwide public domain to the greatest extent possible. Note that some jurisdictions do not allow creators to dedicate their works to the public domain, so CC0 has other legal mechanisms included to help deal with this situation where it applies. (More on this in Section 3.3.) |

| The public domain mark is a label used to mark works known to be free of all copyright restrictions. Unlike CC0, the public domain mark is not a legal tool and has no legal effect when applied to a work. It serves only as a label to inform the public about the public domain status of a work and is often used by museums and archives working with very old works. |

Final remarks

There is a learning curve to some of the terminology and basics about how CC legal tools work. But as you now know, it is far less intimidating than it looks! We will return to look at the CC licences in more depth in Section 3.3.

3.2 Licence scope

Creative Commons licences are built on copyright law. That simple fact tells you most of what you need to know about when they do and do not apply, and how long they last.

Learning outcomes

- describe how CC works with copyright and why this is important

- explain the time length of a licence.

Reflection

Think about why it is important for CC licences to work with copyright. What would it mean if a CC licence conflicted with what was permitted under copyright? (For example, if you were prevented from doing something that you could otherwise do with a copyrighted work, such as printing a copy of a poem to insert into a friend’s birthday card.)

Introduction

What is the legal foundation upon which Creative Commons licences operate? Why is it so important?

Creative Commons licences are copyright licences. They apply where and when copyright applies. This reflects a fundamental design decision by the founders of Creative Commons. Given that the goal was to make more creative and educational works available under common-sense terms, CC wanted to ensure that its licences were not used to restrict works or uses of works that copyright does not restrict. This is a core CC value, and making sure that the language of the licences tracks copyright law accomplished this goal.

Copyright and Creative Commons

The statement that ‘Creative Commons licences are copyright licences’ tells you the following about them:

- Creative Commons licences ‘operate’, or apply, only when the work is within the scope of copyright law (or other related law) and the restrictions of copyright law apply to the intended use of the work. (This is discussed in more detail below.)

- Certain other rights (such as patents, trademarks, privacy and publicity rights) are not covered by the licences, and so must be managed separately.

The first statement explains a basic limitation of the licences in controlling what people do with the work. The second statement provides a warning that there may be other rights at play with the work that restrict how it is used.

Let’s start by unpacking what it means for the licence to apply where copyright applies.

Creative Commons licences are appropriate for creators who have created something protectable by copyright, such as an image, article or book, and want to provide people with one or more of the permissions governed by copyright law. For example, if you want to give others permissions to freely copy and redistribute your work, you can use a CC licence to grant them those permissions. Likewise, if you want to give others permissions to freely transform or alter your work, or otherwise create derivative works based upon it, you can use a CC licence to grant them those permissions.

However, you don’t need to use a Creative Commons licence to give someone permission to read your article or watch your video, because reading and watching aren’t activities that copyright generally regulates.

Two more important scenarios in which a user does not need a copyright licence are:

- when fair use, fair dealing or some other limitation and exception to copyright applies

- when the work is in the public domain – remember from Unit 2 that this depends on the law that applies to your use (where you are using the work) and the copyright law in that country.

Because users don’t need copyright licences in these scenarios, CC licences aren’t needed.

Can you think of reasons why someone might try to apply a CC licence to a work not covered by copyright in their own country? Or reasons why a CC licensor might expect attribution every time their work is used, even for a use that is not prohibited by copyright law?

A CC licensor might be trying to exert control they do not actually have by law. But more likely than not, they simply do not know that copyright does not apply or that a work is in the public domain. Or, for the savvy licensor, they may realise their work is in the public domain in some countries but not public domain everywhere, and they want to be sure everyone everywhere is able to reuse it.

One other subtle but important difference about the scope of CC licences is that they also cover other rights closely related to copyright, called ‘similar rights’. We introduced ‘similar rights’ in Section 1.2 when we looked at the new Myanmar Copyright Act. Just as with copyright, the CC licence conditions only come into play when similar rights otherwise apply to the work and to the particular reuse made by someone using the CC-licensed work.

The other critical part of the statement ‘CC licences are copyright licences’ is that there may be other rights in the works upon which the licence has no effect – for example, privacy rights. Again, CC licences do not have any effect on rights beyond copyright and similar rights as defined in the licences, so other rights have to be managed separately.

While not required, Creative Commons urges creators to make sure there are no other rights that may prevent reuse of the work as intended. CC licensors do not make any warranties about reuse of the work. That means that unless the licensor is offering a separate warranty, it is incumbent on the reuser to determine whether other rights may impact their intended reuse of the work. Learning more can sometimes be as easy as contacting the licensor to inquire about these possible other rights. Read through this complete list of considerations for reusers of CC-licensed works.

What types of content can be CC-licensed?

You can apply a CC licence to anything protected by copyright that you own, with one important exception.

CC urges creators not to apply CC licences to software. This is because there are many free and open source software licences that do that job better because they were built specifically as software licences. For example, most open source software licences include provisions about distributing the software’s source code, and CC licences do not address that important aspect of sharing software. The software sharing ecosystem is well-established, and there are many good open source software licences to choose from. This FAQ from CC’s website has more information about why we discourage our licences for software.

Whose rights are covered by the CC licence?

A CC licence on a given work only covers the copyright held by the person who applied the licence: the licensor. That might sound obvious, but it is an important point to understand. For example, many employers own the copyright to works created by employees, so if an employee applies a CC licence to a work owned by her employer, she is not able to give any permission whatsoever to reuse the work. The person who applies the licence needs to be the creator, or someone who has acquired the rights.

Additionally, a work may incorporate the copyrighted work of another, such as a scholarly article that uses a copyrighted photograph to illustrate an idea (after having received the permission of the owner of the photograph to include it). The CC licence applied by the author of the scholarly article does not apply to the photograph; only the remainder of the work. Separate permission may need to be obtained in order to reproduce the photograph, but not the remainder of the article. (See Section 4.1 for more details on how to handle these situations.)

Also, works often have more than one copyright attached to them. For example, a filmmaker may own the copyright to a film adaptation of a book, but the book author also holds a copyright to the book that the film is based on. In this example, if the film is CC-licensed, the CC licence only applies to the film and not the book. The user may need to separately obtain a licence to use the copyrightable content from the book that is part of the film.

Final remarks

A key to understanding how Creative Commons works is understanding that the licences depend on copyright to function. Copyright explains a lot about when the tools apply and how much of a work they cover.

3.3 Licence types

There are six different CC licences, designed to help accommodate the diverse needs of creators while still using simple, standardised terms.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- explain the CC licence suite

- describe the different CC licence elements.

Reflection

Think about a piece of creative or academic work you made that you are particularly proud of. If you shared that work with others, would you accept them adapting it or using it for commercial purposes? Why, or why not?

Introduction

Why are there so many different Creative Commons licences?

There is no single Creative Commons licence. The CC licence suite (which includes the six CC licences) and the CC0 public domain dedication offer creators a range of options. Creative Commons licences are standardised tools, but part of the vision is to provide a range of options for creators who are interested in sharing their works with the public rather than reserving all rights under copyright.

As we saw earlier in this unit, the four licence elements – BY, SA, NC and ND – can be combined to create six different licence options.

All of the licences include the BY condition. In other words, all licences require that the creator be attributed in connection with their work. Beyond that commonality, the licences vary depending on whether commercial use of the work is permitted, and the work can be adapted (and if so, on what terms).

Introducing the six licence types

The six licences, from least to most restrictive in terms of the freedoms granted reusers, are as follows.

| The Attribution licence or ‘CC BY’ allows people to use the work for any purpose (even commercially and even in modified form) as long as they give attribution to the creator. | |

| The Attribution-ShareAlike licence or ‘CC BY-SA’ allows people to use the work for any purpose (even commercially and even in modified form) as long as they give attribution to the creator and make any adaptations they share with others available under the same or a compatible licence. This is CC’s version of a copyleft licence, and is the licence required for content uploaded to Wikipedia, for example. | |

| The Attribution-NonCommercial licence or ‘CC BY-NC’ allows people to use the work for non-commercial purposes only, and only if they give attribution to the creator. | |

| The Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence or ‘CC BY-NC-SA’ allows people to use the work for non-commercial purposes only, and only if they give attribution to the creator and make any adaptations they share with others available under the same or a compatible licence | |

| The Attribution-NoDerivatives licence or ‘CC BY-ND’ allows people to use the unadapted work for any purpose (even commercially) as long as they give attribution to the creator. | |

| The Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence or ‘CC BY-NC-ND’ is the most restrictive licence offered by CC. It allows people to use the unadapted work for non-commercial purposes only, and only as long as they give attribution to the licensor. |

Distinguishing the licences

To really understand how the different options work, let’s dig into the different licence elements. Attribution is a part of all CC licences, and we will dissect exactly what type of attribution is required in a later unit. For now, let’s focus on what makes the licences different.

Commercial vs non-commercial use

As we know, three of the licences (CC BY-NC, CC BY-NC-SA and CC BY-NC-ND) limit reuse of the work to non-commercial purposes only. In the legal code, a non-commercial purpose is defined as one that is ‘not primarily intended for or directed towards commercial advantage or monetary compensation’. This is intended to provide flexibility depending on the facts surrounding the reuse, without over-specifying exact situations that could exclude some prohibited and some permitted reuses.

It’s important to note that CC’s definition of NC depends on the use, not the user. If you are a non-profit or charitable organisation, your use of an NC-licensed work could still run afoul of the NC restriction; if you are a for-profit entity, your use of an NC-licensed work does not necessarily mean you have violated the term. For example, a non-profit entity cannot sell another’s NC-licensed work for a profit, and a for-profit may use an NC-licensed work for non-commercial purposes. Whether a use is commercial depends on the specifics of the situation. Creative Commons’ NonCommercial Interpretation page has more information and examples.

Adaptations

The other differences between the licences hinge on whether, and on what terms, reusers can adapt and then share the licensed work. As we saw in Unit 1, the question of what constitutes an adaptation of a licensed work depends on applicable copyright law. One of the exclusive rights granted to creators under copyright is the right to create adaptations of their works – or, as they are called in some places, derivative works. (For example, creating a movie based on a book, or translating a book from one language to another.)

As a legal matter, at times it is tricky to determine exactly what is and is not an adaptation. Here are some handy rules about the licences to keep in mind:

- Technical format-shifting (for example, converting a licensed work from a digital format to a physical copy) is not an adaptation, regardless of what applicable copyright law may otherwise provide.

- Fixing minor problems with spelling or punctuation is not an adaptation.

- Syncing a musical work with a moving image is an adaptation, regardless of what applicable copyright law may otherwise provide.

- In Units 4 and 5 we will look at different ways in which you might want to use CC-licensed materials. Reproducing and putting works together into a collection is not an adaptation of the individual works. For example, combining standalone essays by several authors into an essay collection for use as an open textbook is a collection and not an adaptation. Most open courseware is a collection of others’ open educational resources (OER).

- Including an image in connection with text – such as in a blog post, a PowerPoint presentation or an article – does not create an adaptation unless the photo itself is adapted.

Two of the NoDerivatives licences (BY-ND and BY-NC-ND) prohibit reusers from sharing (i.e. distributing or making available) adaptations of the licensed work. To be clear, this means anyone may create adaptations of works under an ND licence as long as they do not share the work with others in adapted form. Among other things, this allows organisations to engage in text and data mining without violating the ND term.

Two of the ShareAlike licences (BY-SA and BY-NC-SA) require that if adaptations of the licensed work are shared, they must be made available under the same or a compatible licence. For ShareAlike purposes, the list of compatible licences is short. It includes later versions of the same licence (so for example, BY-SA 4.0 is compatible with BY-SA 3.0) and a few non-CC licences designated as compatible by Creative Commons (such as the Free Art Licence). You can read more about this here, but the most important thing to remember is that ShareAlike requires that if you share your adaptation, you must do so using the same or a compatible licence.

Public domain

In addition to the CC licence suite, Creative Commons also has an option for creators who want to take a ‘no rights reserved’ approach and disclaim copyright entirely. This is CC0, the public domain dedication tool.

Like the CC licences, CC0 (read ‘CC Zero’) uses the three-layer design: legal code, deed and metadata.

The CC0 legal code also uses a three-pronged legal approach. Some countries do not allow creators to dedicate their work to the public domain through a waiver or abandonment of those rights, so CC0 includes a ‘fallback’ licence that allows anyone in the world to do anything with the work unconditionally. The fallback licence comes into play when the waiver fails for any reason. And finally, in the rare instance that both the waiver and the fallback licence are not enforceable, CC includes a promise by the person applying CC0 to their work that they will not assert copyright against reusers in a manner that interferes with their stated intention of surrendering all rights in the work.

Like the licences, CC0 is a copyright tool, but it also covers a few additional rights beyond those covered by the CC licences, such as non-competition laws. From a reuse perspective, there may still be other rights that require clearance separately, such as trademark and patent rights, and third party rights in the work, such as publicity or privacy rights.

Final remarks

Creative Commons legal tools were designed to provide a solution to complicated laws in a standardised way, making them as easy as possible for non-lawyers to use and apply. Understanding the basic legal principles in this unit will help you use the CC licences and public domain tools more effectively.

3.4 Licence enforceability

Creative Commons licences were carefully crafted to make them legally enforceable in countries around the world.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- describe the state of Creative Commons case law

- understand the different licence versions and why changes were made.

Reflection

Whether you or your organisation is using CC licences or you are advising others in their use, you want to be confident that the terms of the CC licences are enforceable. If someone misuses your work, what recourse do you have? What would you do if you found out someone was using your CC-licensed photograph in a magazine without giving you credit, for example?

Introduction

Creative Commons licences are legal tools that build on copyright law. As legal instruments, CC licences need to stand up in court. What happens when there is a court case that involves Creative Commons licences? What happens if someone is violating the CC licence you applied to a work, but you do not want to file a lawsuit? What happens if a licensor complains about how you have attributed them when reusing their work?

To date and to our knowledge, no court around the world that has heard a case involving a CC licence (of which there have been very few) has questioned the validity or enforceability of a CC licence. Thanks to the CC community, most disputes connected to CC licences are resolved outside of court and often without involving lawyers.

Most people who reuse CC-licensed works try to comply with the licence conditions. But whether well-meaning or not, sometimes people get it wrong.

The legal enforceability of CC licences

If someone is using a CC-licensed work without giving attribution or otherwise following the licence, their right to use the work ends automatically as soon as they violate the terms. Unless the person using the work received separate permission or is relying upon fair use or some other exception to copyright, they are potentially liable for copyright infringement. Read this FAQ about what happens when someone does not comply with a CC licence. Read this FAQ for a look at what happens from the perspective of a reuser.

As we saw earlier, CC licences work with copyright, so legal enforceability is one of the key features of CC licensing. While the licences are widely seen as symbols of free and open sharing, they also carry legal weight. The legal code was written by lawyers with the help of a global network of international copyright experts. The result is a set of terms and conditions that are intended to operate and be enforceable everywhere in the world.

Licence versions

As we saw earlier, there are different versions of CC licences. Not to be confused with the different types of licences described in Section 3.3, the licence version number simply represents when that particular version of the legal code was written.

CC improves its licences through the process of versioning, which is the process by which we update the legal code to better account for changes in copyright law and technology, and the needs of reusers. While there are some differences between licence versions, the different versions are largely the same in practical effect. The latest version of the CC licence suite is version 4.0, which was published in 2013. Details on what updates were made to the licences in version 4.0 can be found on the CC wiki. For the most definitive and comprehensive view of how the licences have changed from Version 1.0 to the present, including all changes to the attribution and marking requirements, visit the Creative Commons website.

One important difference between the newest version of CC licences (version 4.0) and prior versions relates to violations of CC licence terms. Version 4.0 CC licences enable a licensee who has broken the terms of a licence (for example, if they forgot to attribute) to have their right to use that resource reinstated if they correct the violation within 30 days. You can find out more about this in the section ‘30-day window to correct licence violations’ on the What’s New in 4.0 page on the CC website.

Another major difference is that prior to version 4.0, Creative Commons gave permission to the CC Global Network to ‘port’ the Creative Commons licences. Porting involved linguistic translation and adjustments so that the licences reflected local terminology and drafting protocols, and accounted for other local differences, such as the existence of moral rights and collecting societies.

One of the primary reasons for versioning the licences from 3.0 to 4.0 was to eliminate the need for porting, an unnecessarily complex process that could be eliminated if CC took proper care to ensure the new licences were internationalised. Starting with version 4.0 (the most recent version of the CC licence suite), CC no longer ‘ports’ the licences. The ported licences of previous versions may still be used and remain legally valid and enforceable; however, Creative Commons discourages their use and recommends version 4.0 as the latest and most up-to-date thinking of CC and its global network.

Ported versions of the licences are different to the official translations of CC licences. The latest versions of all CC legal tools may be translated into official versions in other languages. You can find out more about translation of CC licences in the additional resources section.

In all cases, it is recommended by CC that creators use the latest version of the licences, as it reflects the latest thinking of Creative Commons and its global network of legal experts. Remember that some platforms where you can share your resources require you to apply particular licences: for example, the image-sharing platform Flickr uses the 2.0 version of CC licences).

Final remarks

The legal robustness of the CC licences is critically important. With the help of its international network of legal and policy experts, the CC licences are accepted and enforceable worldwide. To date, no court has declared the licences unenforceable, and very few lawsuits have ensued. In the vast majority of cases, the community resolves disputes outside of the courtroom.