Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 22 November 2025, 2:55 AM

Unit 4: OER and using CC-licensed work

Introduction

Now that you know how the licences work and how they are designed, let’s look at why you might want to use openly licensed material. Where can you find CC-licensed material? How can you evaluate and reference it properly?

This unit has four sections:

- 4.1 Open educational resources (OER)

- 4.2 Why use OER?

- 4.3 Finding and evaluating OER

- 4.4 Attributing OER

There are also additional resources if you are interested in learning more about any of the topics covered in this unit.

4.1 Open educational resources

You may have heard the expression ‘open educational resources’ (OER) before. What does it mean for educational resources to be ‘open’? What is the relation between CC licences and OER?

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- define ‘open’ in the context of OER

- understand the relationship between OER and CC licences

- differentiate between OER, open textbooks, open courses and MOOCs.

Reflection

What does ‘openness’ mean to you? Do you think that all CC licences could be described as ‘open’?

Introduction

This section of the course introduces you to the concept of ‘open’ educational resources and contextualises OER in relation to CC licensing. What kinds of resources could be ‘open’? In the next section of this unit we will then look at some of the reasons we might want to use OER.

We will also consider why the ‘open’ element is particularly important when we are thinking about choosing and applying a CC licence to our work.

Open educational resources (OER)

What makes open educational resources ‘open’? Let’s take a look at this definition from UNESCO:

‘Open educational resources (OER) are any type of educational materials that are in the public domain or introduced with an open licence. The nature of these open materials means that anyone can legally and freely copy, use, adapt and re-share them. OERs range from textbooks to curricula, syllabi, lecture notes, assignments, tests, projects, audio, video and animation.’ (UNESCO, n.d.)

As you can see, OER can take many different forms, from lecture notes to textbooks. They can be described as ‘open’ because the resources are available on an open licence or are in the public domain. However you can also see that resources are ‘open’ because ‘anyone can legally and freely copy, use, adapt and re-share them’.

Do all Creative Commons licences enable us to do all these things?

Another way of expressing the ‘openness’ of OER is David Wiley’s 5Rs. David Wiley is a key figure in the open education movement. The 5Rs is a series of rights that the creator of an OER gives to a user, including the right to:

- ‘retain’ a work (in other words, to keep a copy of it)

- ‘reuse’ material (without seeking permission, as you have already been granted this according the terms of the open licence that’s been applied to the resource)

- ‘revise’ the material (to make changes to a resource)

- ‘remix’ a resource (to combine the resource with other OER to make something new)

- ‘redistribute’ the openly licensed material (in other words, to share it with others).

(Here is Wiley’s original definition of the 5Rs.)

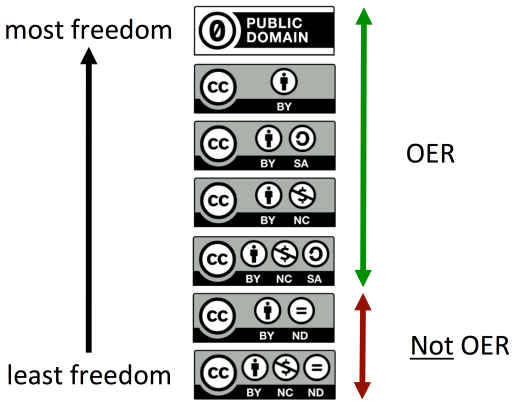

Not all education materials available under a CC licence are OER. The following figure details which CC licences work well for education resources and which do not. What CC licence types are described as ‘not OER’ and ‘least free’? Why do you think they have been described this way?

As you might have recognised, the two licence types that are described as ‘not OER’ and the ‘least free’ include the ‘ND’ or no-derivatives licence element. This is because the ND licence element prohibits you from making changes to a resource and then sharing it with others.

ND licences do not fulfil the UNESCO definition of OER because you cannot ‘adapt’ ND-licensed material that you want to share with others. ND-licensed resources do not meet the criteria of David Wiley’s 5Rs either because they do not grant the user permission to ‘remix’ and ‘revise’ a resource.

Choosing the right licence for your OER requires you to think about which permissions you want to give to other users, and which permissions you want to retain for yourself. Many open education advocates support the use of the CC BY licence for educational purposes because it grants the user the most permissions for reuse and reversioning. You can find out more about why CC BY in the additional resources section. We’ll also take a closer look in Sections 4.2 and 5.2 at what you need to consider when applying a CC licence to your own work and why it might be important to choose a licence that enables adaptation.

Open textbooks

OER come in all shapes and sizes: as small as a single video or simulation, or as large as an entire degree programme. It can be quite difficult, or at least time-consuming, for teachers to assemble OER into a collection comprehensive enough to replace a copyrighted textbook. For this reason, OER are often collected and presented in ways that resemble a traditional textbook in order to make them easier for instructors to understand and adopt.

The term ‘open textbook’ simply means a collection of OER that have been organised to look like a traditional textbook in order to ease the adoption process. To see examples of open textbooks in a number of disciplines, visit OpenStax, the Open Textbook Library or theBC Open Textbook Project. OER can also be aggregated and presented as digital courseware, such as MIT OpenCourseWare.

Open courses and MOOCs

In 2007, David Wiley and Alec Couros began experimenting with ‘open courses’. The idea of an open course was to make the syllabus, readings, videos and other resources used to teach a class formally offered at a university available to the public and to invite the public to participate in the course by reading, watching videos, participating in discussions on social media, and completing assignments in collaboration with the course’s official students. The informal participants did not receive credit from the universities, but they also did not have to apply for admission or pay tuition. Running an open course required instructors to use OER so that they could be accessed and used by all course participants, both formal and public.

In 2008, George Siemens and Stephen Downes jointly offered an open course on Connectivism and Connected Knowledge (CCK08). This course attracted many more public participants than either of the 2007 courses led by Wiley and Couros – more than 2000 learners participated. This large number led Dave Cormier to refer to CCK08 as a ‘massive open online course’ or MOOC, a reference to the massively multiplayer online role-playing games that became popular in the late 1990s.

Today, several for-profit and non-profit MOOC providers exist, including edX, Coursera and FutureLearn. While they all provide free access/open admission to their courses to the public, none of these organisations are committed to creating or using OER like the authors of the original MOOCs were. The pedagogy of these later MOOCs also differs significantly from the diverse, connected practices of the early MOOCs.

Recent MOOCs have generally become much more uniform and sterile, and generally consist of watching short videos and answering questions. Tony Bates describes MOOCs based on the earlier open and exploratory model as cMOOCs, and the more homogenised and corporate style as xMOOCs.

Final remarks

OER, whether organised as open textbooks or open courseware, provide teachers, learners, and others with a broad range of permissions that make education more affordable and more flexible. These permissions also enable rapid, low-cost experimentation and innovation, as seen by the early MOOCs.

4.2 Why use OER?

Now that we’ve introduced OER, why might this type of resource be useful?

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will have considered some of the reasons why CC-licensed resources and OER could be useful for your university.

Reflection

Think about the kind of resources that you use at your university. Why and how might CC-licensed resources be useful?

Introduction

With the introduction of Myanmar’s new Copyright Act, it is essential to ensure that you seek appropriate permission to use copyrighted resources, as required. As we saw earlier, resources that are openly licensed do not require permission to share or copy them. This section of the course looks at more reasons why you might want to use CC-licensed materials or look for CC resources on more ‘open’ licences, such as those that enable changes to be made to the resource.

Whatever resources you are using, whether CC-licensed or copyrighted, it is essential to reference what you use. We will take a closer look at referencing in Section 4.4.

Reasons to use OER and CC-licensed resources

As we saw in the last section, not all CC-licensed materials give permission for you to make changes to them. However, resources with the ND or no-derivatives element do enable sharing and copying of the resource – sometimes even for commercial purposes. Even though you cannot make changes to ND-licensed material, they may be useful for reference or as a supporting resource at your university. In the next section we’ll look in more detail about what you should consider when you’re looking for openly licensed resources, and where to find them.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the other reasons why we might want to use CC-licensed material and OER:

- Resources with open licences have clear instructions on what you can and can’t do with them.

- It is easier to use CC-licensed materials as you don’t have to seek permission and/or pay a fee to the copyright holder. This can save time and money.

- Some resources with more permissive CC licences – those that enable changes to be made to the resource, for example – can be adapted to better suit the context they will be used in. This is often referred to as ‘localisation’. Localising existing resources can save time as you don’t need to start afresh to create new material.

- Many openly licensed resources are in English. Although more OER in different languages and reflecting different contexts is needed, within the Myanmar university context this means that there are many existing resources that could be considered for use. Many of these resources could also be translated, if permitted by the licence type.

- Incorporating different OER into teaching and learning materials can provide different perspectives or ways of explaining concepts to students.

- Openly licensed resources increase access to educational material by providing resources to everyone, not only those who can afford to buy particular books. You could curate collections of OER to build stock in the library or to support existing courses.

- Finally, the idea of OER is strongly advocated around the world by a broad range of individuals, organisations, and governments, as evidenced by documents like the Cape Town Open Education Declaration (2007), the UNESCO Paris OER Declaration (2012), and the UNESCO Ljubljana OER Action Plan (2017) and the UNESCO OER Recommendation (2019).

Reflection

Do these reasons for using openly licensed material resonate with you? Can you think of other reasons to add to the list? What reasons might resonate best with colleagues or students?

Final remarks

This section looked at some of the reasons why you might want to consider using openly licensed resources at your institution. In Unit 6 we will consider next steps and different ideas for how to raise awareness and support colleagues in their use of OER and understanding of the new Myanmar Copyright Act.

4.3 Finding and evaluating OER

There are more than a billion CC-licensed works on the web. How do you find what might be useful to you, your students or colleagues? And once you have found a useful resource, what do you need to do when you reuse it?

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- search and give proper attribution to openly licensed resources you find.

- find OER in open repositories, Google, CC Search and other platforms

- evaluate openly licensed resources.

Reflection

Where do you currently find resources for teaching and learning? What criteria do you use to select material? What additional criteria might be needed to evaluate the suitability of OER?

Introduction

What skills and knowledge are needed to find the OER that your teachers and students need?

This section of the course looks at some of the places where you can find OER and criteria you might want to consider when reviewing resources. In Unit 5 we’ll look at how to create different types of OER. Many of the places you look for OER are also places where you can share your work and showcase the work of your university.

Where to look for OER

There are lots of places to find openly licensed resources. Some websites curate OER into discipline, education level and/or resource type. Other websites include search functionality that enable us to refine our searches to only include openly licensed resources or other criteria.

Let’s take a closer look at other places to find CC-licensed material. Section 4.1 on OER includes many useful places to find specific types of openly licensed resources such as courses and textbooks. If you are looking for these types of resources, you may want to search these. Remember that different countries use different terminology for some disciplines. For example, ‘life sciences’ refers to disciplines including zoology, botany and biology, whilst ‘social science’ include subjects such as geography and economics. Different countries also have different education systems and you may need to think about what level the resources are labelled as being appropriate for, and whether this corresponds to your students’ needs.

You may already be familiar with eTekkatho, which enables offline access to digital OER in universities, colleges and schools across Myanmar. ACU-OER promotes collaboration, open education and shares OER across the ASEAN region. The Myanmar Information Management Unit (MIMU) provides country data and information that can be used with attribution. Open Development Myanmar provides CC BY-SA licensed tools and data.

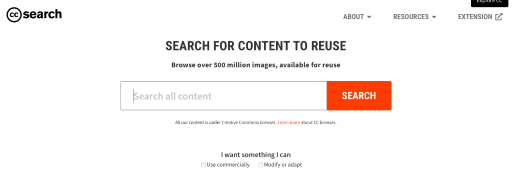

Other useful tools include CC Search, which is a tool that lets you search 500 million openly licensed images.

Many platforms that enable CC licensing of works shared on their sites also have their own search filters to find CC content, like OER Commons. You can also filter searches on Google, Flickr and YouTube to look for openly licensed content or material with a CC licence.

If there is a particular type of content you are looking for, you may be able to narrow down particular sources to explore. Wikipedia offers a comprehensive listing of many major sources of CC material across various domains.

You can also search for works under a particular CC licence. Take a look at the Creative Commons overview of each licence that includes examples of projects and people using those licences:

When you find a work you would like to reuse, it is important to provide proper attribution for that resource. Do you remember the Title, Author, Source and Licence (TASL) from Section 3.1? We’ll take a closer look at how to use TASL to attribute a resource in Section 4.4.

Finally, you can also search for regionally specific OER using the OER World Map. For example, here is an overview of OER in Thailand.

Evaluating resources

As with any educational resources you use, OER need to be evaluated before use. The process of using and evaluating OER is not that different from evaluating traditional ‘all rights reserved’ copyright resources. Whether education materials are openly licensed or closed, you and your colleagues are the best judge of quality, as you know what students need and how a resource will be used.

Let’s take a closer look at what you might want to consider when assessing educational materials. JISC provides a list of criteria for assessment of quality:

- accuracy

- reputation of author/institution

- standard of technical production

- accessibility

- fitness for purpose.

One important consideration when evaluating OER is whether you intend to adapt or make changes to the material by combining it with other openly licensed resources. As we’ll see in the next unit, some CC licence types cannot be combined to create new resources because their licences are incompatible. This means that if you are looking for openly licensed material to adapt, you need to be particularly mindful of the licence type of the resources you select. This means that you need to think ahead! The role of librarians, ICT and support staff is particularly important in this respect, because you can support teachers in selecting material and ensure that it is fit for purpose, depending on what it is needed for.

When you evaluate resources, you may also want to consider the format of the resource. Myanmar is often described as a ‘mobile-first country’, but unfortunately not all OER are currently optimised for use on mobile devices. If you are a technical member of staff, you may be able to support colleagues in choosing the most appropriate OER and advising further on this aspect.

Reflection

When you are considering different resources you might also want to consider how different students will access material. Data can be expensive and although day students may be able to use campus Wi-Fi or offline services such as eTekkatho to access resources, how could you support distance education students access to resources? Could you download and supply resources to students and educators offline? Could curated OER be supplied to distance education students when they register at your university or when they come for examinations?

Your own practice

As we’ve seen, librarians and other ICT and support staff have an important role in supporting colleagues in finding OER and using it correctly. Here’s a few good practice suggestions to help you get started:

- When you’re searching for openly licensed resources, it’s important to keep a record of where you found material, who created it and what CC licence it uses, so you can attribute properly. We’ll find out more about attribution in the next section. You may want to create a separate document (sometimes called an ‘asset log’) to help you keep this information in one central place. You should also save the downloaded resource in a central location. Keeping a record of how you use different OER is particularly important when you are working on complex projects such as developing an open course that incorporates existing material. We will look at some examples of this in Unit 5.

- If you’re working with colleagues to find OER, or finding openly licensed content yourself, it is important to review and check each resource you’d like to use. Remember to proceed with caution when you find a resource with no creator or licensing information. Could you find an alternative resource to use? Sometimes you may need to go back to the original website where the creator uploaded the resource to find the information you need. Remember that one of the benefits of openly licensed material is that it should provide clear information about the creator and how they want you to reuse the resource.

- Finally, you might already have resources you’d like to use, but have forgotten where you originally found them. Can you use them without breaching copyright? Are they openly licensed? If the resource is an image, you can perform a Google reverse image search to find the picture and information about its creator and copyright information. Otherwise you may be able to use a search engine to find the original resource by using key terms.

Final remarks

We live in an amazing world of information abundance, and an increasing percentage of our digital knowledge is openly licensed. Finding the right open resources that fit the needs of your learning spaces and your students can be a challenge. One of the major motivations for using OER is the ability to revise, remix and share these works to best suit the needs of teachers and students.

4.4 Attributing OER

Now you’re able to find suitable openly licensed resources, let’s take a closer look at how to attribute them.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- attribute a CC-licensed resource

- reflect on current referencing practices.

Reflection

How do you usually acknowledge others’ work? Why might it be important to reference the resources we use?

Introduction

Whether openly licensed or not, all resources need to be referenced properly. As we saw earlier, Section 27 of the new Myanmar Copyright Act also requires you to reference any material that you are permitted to use for educational purposes.

This section looks at what information we need to reference CC-licensed resources. In Unit 5 we look at how to reference different uses of openly licensed materials, for example, where we are permitted to make changes to a resource or in instances where we combine different openly licensed materials (perhaps with our own work) to create a new resource. We will also see that the information we use to attribute others is also the information we need to include when we apply an open license to our own work.

Attribution basics

When you are looking for OER, you need to check you have all the information you need to attribute a resource properly. This is where your asset log may be useful!

You might remember from earlier in the course that we are legally required to attribute all CC-licensed resources. This is because all CC licences include the ‘BY’ element. You may also recall from Unit 2 that public domain and material marked with the CC0 tool do not require attribution. However, it is often considered good practice to provide a reference for this type of resource, because it helps other users to find the original resource.

The best practice for attribution is to include the following pieces of information in an attribution.

- T = Title

- A = Author

- S = Source

- L = Licence

This is described as the ‘TASL’ approach. If an author has provided extensive information in their attribution notice, retain it where possible.

Look back through the course and in the Acknowledgements section to see how images and other materials used in this course have been attributed.

The attribution requirements in the CC licences are purposefully designed to be fairly flexible to account for the many ways that content is used. A filmmaker will have different options for giving credit than a scientist publishing an academic paper. Explore this page about best practices for attribution on the CC wiki. Among the options listed, think about how you would prefer to be attributed for your own work.

Creative Commons is also exploring ways to automate attribution. Take a look at this page of results from the CC search tool. Click on a couple of different photos to see how attribution is given, and experiment with the ‘copy credit as text’ and ‘copy credit as HTML’ functions. Open Attribute also provide a tool to enable easy CC attribution. There is a Creative Commons Microsoft Office Add-in for adding attributions to Word, Excel and Powerpoint.

The other main consideration when copying works (as opposed to remixing, which will be covered in Unit 5) is the NC or non-commercial restriction. If the work you are using is published with one of the three CC licences that includes the NC element, then you need to ensure that you are not using it for a commercial purpose.

Remember, you can contact the creator if you want to request extra permission beyond what the licence allows.

Final remarks

Attribution is arguably the single most important aspect of Creative Commons licensing. Think about why you want credit for your own work, even when it may not be legally required. What value does attribution provide to authors, and to the public who comes across the work online?