Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 7 May 2024, 7:40 AM

Unit 5: Creating CC-licensed work

Introduction

Now that we can attribute a CC-licensed resource created by others, let’s take a closer look at applying a CC licence to our own work and to work that we create by adapting OER.

In Unit 4 we looked at where to find openly licensed resources and how to evaluate them. We also looked at what information we need to provide when we reference or attribute a CC-licensed resource. This unit takes a deeper look at choosing and applying CC licences to your own work, and reviews what you should consider to make your resource easy to find and reuse. Finally, we also look at adapting openly licensed resources and how to attribute resources we create that blend a range of OER together in different ways.

This unit has three sections:

- 5.1 Choosing and applying a CC licence

- 5.2 Things to consider after CC licensing

- 5.3 Adapting and Remixing CC-licensed work

There are also additional resources if you are interested in learning more about any of the topics covered in this unit.

5.1 Choosing and applying a CC licence

The act of applying a CC licence is easy, but there are several important considerations to think through before you do.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- name the most important considerations before applying a CC licence or CC0

- apply a licence using CC’s licence chooser and CC0 using CC’s public domain dedication

- evaluate which licence to apply based on relevant factors.

Reflection

How would you go about choosing a particular CC licence for your work? Do you know how to attach a licence to your work? Can you change your mind about the licence? This unit will help you answer these questions.

Introduction

What should creators consider before applying a CC licence or CC0 to their work? There are several options for creators who choose to share using CC licences. There are also many things to think about before applying any CC licence or CC0, including whether you have all the rights you need and if not, how you must indicate that to the public.

Before you decide that you want to apply a Creative Commons licence or CC0 to your creative work, there are some important things to consider:

The licences and CC0 are irrevocable

‘Irrevocable’ means a legal agreement that cannot be cancelled. That means once you apply a CC licence to a work, the licence applies until the copyright on the work expires. This aspect of CC licensing is highly desirable from the perspective of reusers, because they have confidence knowing that the creator can’t arbitrarily pull back the rights granted them under the CC licence.

Because the licences are irrevocable, it is very important to carefully consider the options before deciding to use a CC licence on a work.

You must own or control copyright in the work

You should control the copyright of any work that you apply a licence to. For example, you don’t own or control any copyright in a work that is in the public domain, and you don’t own or control the copyright to, for example, a May Sweet song.

Further, if you created the material in the scope of your employment, you may not be the holder of the rights and may need to get permission from your employer before applying a CC licence. Before licensing, be mindful about whether you have copyright to the work to which you’re applying a CC licence.

Which Creative Commons licence should I use?

The six Creative Commons licences provide a range of options for creators who want to share their work with the public while still retaining copyright. The best way to decide which licence is appropriate for you is to think about why you want to share and how you hope others will use your work.

For example, here are a few questions to consider:

- Do you think people might make interesting new works out of your creation? Do you want to give people the ability to translate your writing into different languages, or otherwise customise it for their own needs? If so, you should choose a licence that allows your work to be adapted.

- Is it important to you that your images can be added to Wikipedia? If so, you should choose CC BY, BY-SA or CC0, because Wikipedia does not allow images licensed under any of the NonCommercial or NoDerivatives licences except in limited circumstances.

- Do you want to give away all your rights in your work so that it can be used by anyone in the world for any purpose? If so, you might want to think about using the public domain dedication tool, CC0.

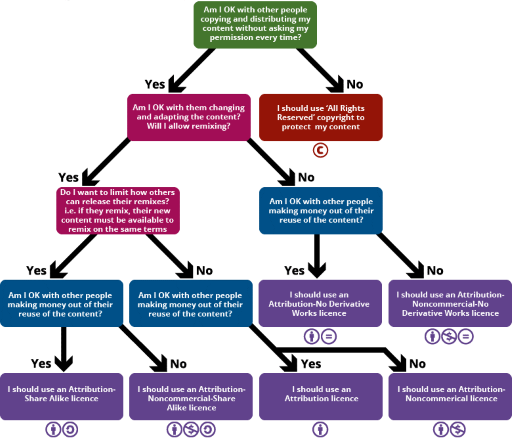

If you need some help deciding which licence might be best for you, this adapted flowchart from CC Australia might be useful – but please note that the information it contains is not legal advice. Starting at the top of the chart, the chart asks a series of questions to help you determine which CC licence would work best for your needs.

How do I apply a CC licence to my work?

Once you’ve decided you want to use a CC licence and know which licence you want to use, applying it is simple. Technically, all you have to do is indicate which CC licence you are applying to your work. However, we strongly recommend including a link – or writing out the CC licence URL, if you are working offline – to the relevant CC licence deed. For example, if you wanted to use the Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)licence, the link to include would be https://creativecommons.org/ licences/ by/ 4.0.

You can do this in the copyright notice for your work, on the footer of your website or at any other place that is suitable in light of the particular format and medium of your work. The important thing is to make it clear what the CC licence covers and locate the notice in a place that makes that clear to the public. See ‘Marking your work with a CC licence’ for more information.

Indicating which CC licence you choose can be as simple as this notice from the footer of BC Open Textbooks:

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

If you are on a platform such as YouTube or Flickr, you should use the built-in tools to mark your work with the CC licence you choose. Remember that some platforms, like Flickr, will mark your work with a particular licence version (e.g. 2.0).

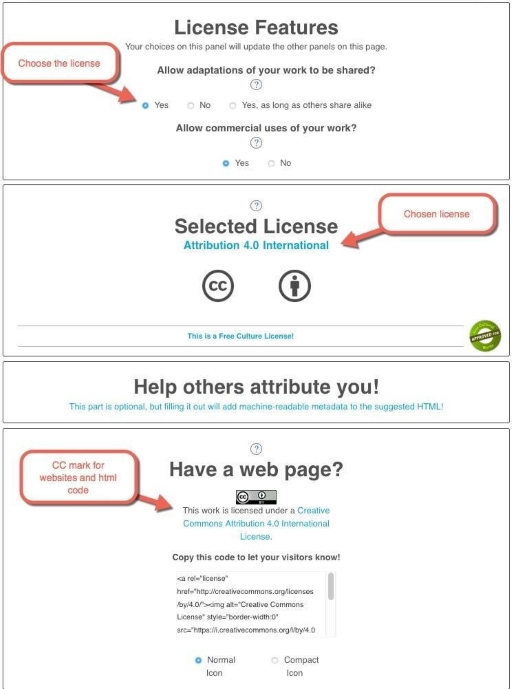

Look at the CC licence chooser, which has been designed to help you select the most appropriate licence for your work. After you select the boxes that indicate your preferences, the chooser generates the appropriate licence based on your selections. Remember, the licence chooser is not a registration page; it simply provides you with standardised HTML code, icons and licence statements.

For examples of CC licences applied to different creations, from videos to offline documents, you should visit a CC wiki on marking your work with a CC licence and explore Creative Commons’ licensing examples page.

Do you see the text and icon just above the code? That can also be copied and pasted onto your work to mark the work with a CC licence.

Like the licences, CC0 has its own chooser. If you want to dedicate your work to the public domain, you can go to https://creativecommons.org/ choose/ zero/ waiver. Complete the required fields, agree to the terms and then get the metadata to mark your work with CC0.

If you want to mark the work in a different way or need to use a different format (such as closing titles in a video), you can visit https://creativecommons.org/ about/ downloads/ and access downloadable versions of all of the CC icons.

Whatever method you use to mark your content, there are several important steps for proper CC licence marking. There are three cases in which you will mark CC-licensed works, which will be discussed in detail in the following sections:

- marking your own work

- indicating if your work is based on someone else’s work

- marking work created by others.

Marking your own work

The first case is marking your own work so that others can easily discover, reuse it and give you credit/attribution. The best practice for marking your work is to follow the TASL approach for your own portions of the content, and for the portions of the content created by others:

- T = Title

- A = Author (tell reusers who to give credit to)

- S = Source (give reusers a link to the resource)

- L = Licence (link to the CC licence deed)

When providing attribution, the goal is to mark the work with full TASL information. When you don’t have some of the TASL information about a work, do the best you can and include as much detail as possible in the marking statement.

Starting with version 4.0, the licences no longer require a reuser to include the title as part of the attribution statement. However, if the title is provided, then CC encourages you to include it when attributing the author.

For more examples of how to mark your own work in different contexts, spend some time looking through CC’s extensive marking page.

See below for an example of marking an image with TASL information. The following image is a good example of CC marking because TASL with all appropriate links is provided in the attribution statement.

Indicating if your work is based on someone else’s work

The second case is indicating if your work is based on someone else’s work. If your work is a modification or derivative of another work, indicate this and provide attribution to the creator of the original work. You should also include a link to the work you modified and indicate what licence applies to that work.

For example, you might want to make a minor change to the picture above. In the instance below, the photo has been desaturated:

A good attribution for this modified version would be:

Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco by tvol used under CC BY 2.0/desaturated from original.

The attribution includes the title, author, source and licence for the original photo, and also indicates how the original photo has been modified.

For other instances where you have made minor changes to a resource, you could also use a statement such as the following:

Adapted from Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco by tvol used under CC BY 2.0.

Sometimes you may want to make more substantial changes to a resource. In these instances, you may have created a derivative work. Let’s look at this example, where a new work (called ‘90fied’) has been created, using the image above:

The attribution statement for this new work should include both TASL details for the new work, ‘90fied’ and details of the original photo ‘Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco’. A good attribution could be:

This work ‘90fied’ is a derivative of Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco by tvol used under CC BY 2.0. ‘90fied’ is licensed under [licence type] by [your name].

‘Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco’ is licensed CC BY 2.0. Once you begin to create derivative works, you need to pay attention to how you license your new creations. We will take a closer look at derivatives and what licences could be applied to the work ‘90fied’ in Section 5.3.

Marking work created by others

The third and final case is marking work created by others that you are incorporating into your own work. It is important to appropriately reference every resource that you incorporate into your own work. We’ll take a closer look at how to do this in Section 5.3.

You should always make it easy for others to know who created what parts of the work and under what terms they can use it. To do this, you should:

- identify the terms under which any given work, or part of a work, can be used

- provide information about works you used to create your new work or incorporated into your work.

Final remarks

When applying a CC licence to a work, you should:

- use the CC licence chooser to determine which CC licence best meets your needs (apply the licence code if possible, or copy/paste the text and links provided)

- (if you are using an online platform) use the built-in CC licence tools to mark your work with a CC licence

- mark your work and give proper attribution to others’ works using the TASL approach.

There is no single answer for which CC licence is the best. Before making your CC licence choice it is important to remember why you are sharing and what you hope others might do with your work.

5.2 Things to consider after CC licensing

Applying a CC licence alone is not enough to ensure your work is freely available for easy reuse and remix.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course you will be able to:

- explain why CC discourages changing the licence terms

- describe why the technical format of content is significant

- describe what happens when someone changes their mind about CC licensing

- understand the importance of making your OER accessible and visible.

Reflection

Have you ever found a CC-licensed work that you weren’t easily able to copy and share? What made it hard to reuse? Were there technical format issues, access restrictions on the work, or something else?

Introduction

What do we need to consider when we create a CC-licensed resource? This section of the course considers some questions we might have about using CC licences. We also consider the importance of making your OER accessible to others and visible.

Questions about open licences

Here’s some common questions about CC licences, and their answers. You can find more questions and answers about CC licences in the frequently asked questions section of the Creative Commons website.

Can I customise a CC licence?

One of the most important aspects of Creative Commons licences is that they are standardised, meaning that the terms and conditions are the same for all works subject to the same type of CC licence. This makes it much easier for the public to understand how the licences work and what reusers have to do to meet their obligations.

But CC licences do not apply to works in a vacuum. CC-licensed works usually live on websites that have their own terms of service. Sometimes, they are not in formats that make it easy to reuse or adapt them. And the works are often available in hard copy form for a price.

But people and institutions who use the licences have diverse needs and wants. Sometimes creators want slightly different terms rather than the standard terms that CC licences offer.

We strongly discourage people from customising open copyright licences, because it:

- creates confusion

- requires users to take the time to learn about how the custom licence differs

- eliminates the benefits of standardisation.

If you change any of the terms and conditions of a CC licence, you cannot call it a Creative Commons licence or otherwise use the CC trademarks. This rule also applies if you try to add restrictions on what people can do with CC-licensed work through your separate agreements, such as a website’s terms of service. For example, your website’s terms of service can’t tell people that they can’t copy a CC-licensed work (if they are complying with the licence terms). You can, however, make your CC-licensed work available on more permissive terms and still call it a CC licence – for example, you may waive your right to receive attribution.

Creative Commons has a detailed legal policy outlining these rules, but the best way to apply them is to ask yourself whether what you want to do will make it easier or harder for people to use your CC-licensed work. If the latter, generally it’s a restriction and you can’t do it – unless you remove the Creative Commons name from the work.

Note that all of the above applies to creators of CC-licensed work. You can never change the legal terms that apply to someone else’s CC-licensed work.

Can I sell a CC-licensed work?

If you are the creator, then selling your work is always okay. In fact, selling physical copies (such as a textbook) and providing digital copies for free is a very common method for making money while using CC licences. For, example OpenStax textbooks are available at no cost on their website, but the hard copies are sold for around US$40.

Charging for access to digital copies of a CC-licensed work is more difficult. It is permissible, but once someone pays for a copy of your work, they can legally distribute it to others for free under the terms of the applicable CC licence.

If you are charging for access to someone else’s CC-licensed work – whether a physical copy or digital version – you have to pay attention to the particular CC licence applied to the work. If the CC licence includes the NonCommercial (NC) restriction, then you cannot charge the public to access the work.

What if you change your mind about the CC licence?

Inevitably, there are creators who apply a CC licence to a work and then later decide they want to offer it on different terms. Even though the original licence cannot be revoked, the creator is free to:

- also offer the work under a different licence

- remove the copy of the work that they placed online.

In those cases, anyone who finds the work under the original licence is legally permitted to use it under those terms until the copyright expires. As a practical matter, reusers may want to comply with the creator’s new wishes as a matter of respect.

What if someone does something with my CC-licensed work that I don’t like?

As long as users abide by licence terms and conditions, authors/licensors cannot control how their material is used. That said, all CC licences provide several mechanisms that allow licensors to choose not to be associated with their material, or to use of their material that they disagree with:

- All CC licences prohibit using the attribution requirement to suggest that the licensor endorses or supports a particular use.

- Licensors may waive the attribution requirement, choosing not to be identified as the licensor, if they wish.

- If the licensor does not like how the material has been modified or used, CC licences require the licensee to remove the attribution information upon request. (In version 3.0 and earlier, this is only a requirement for adaptations and collections; in version 4.0, this also applies to the unmodified work.)

- Finally, anyone modifying licensed material must indicate that the original has been modified. This ensures that changes made to the original material – regardless of whether the licensor approves of them – are not attributed back to the licensor.

Further, it is important to remember that:

- there is not much ‘abuse’ of openly licensed works – most users of CC-licensed work are responsible and abide by the relevant licensing terms

- copyright and/or open copyright licences doesn’t keep ‘bad’ people from doing ‘bad’ things with your work if they don’t care about copyright.

Ensuring OER is accessible and visible

Let’s take a closer look at what you should consider to both make your work visible and accessible.

Accessibility and access

At its core, OER is about making sure everyone has access. Not just rich people, or people who can see and hear, or only people who can read English or Myanmar language – everyone.

As authors and institutions build and share OER, best practices in accessibility need to be part of the instructional and technical design from the start. Universities have a responsibility to ensure learning resources are fully accessible to all learners, including those with disabilities. Watch the English-language ‘Simply said: understanding accessibility in digital learning materials’ by the National Center on Accessible Educational Materials. You can also read more about best practice in openness and pedagogy in this course extract from Maricopa Community College. If you are interested in finding out more about learning design you can also review a range of resources from The Open University (UK). Could these materials be useful to colleagues?

Even if you do not develop courses or material yourself, how can you support students at your university to access resources? Myanmar National Association of the Blind has information and resources on making resources accessible, including the Burmese to Text Speech Software. Read this Frontier Myanmar article on disability rights and education (English language), which reflects on current support and access to education for disabled students in Myanmar.

Formats

Simply applying a CC licence to a creative work does not necessarily make it easy for others to reuse and remix it. Think about the following points:

- What technical format you are using for your content? (For example, PDF, MP3, or something else?)

- Can they easily edit or remix it if the licence allows?

- Can you provide the resource in multiple formats to enable editing and remix? For example, text could be shared in open doc, Word and RTF formats.

- Can people download your work?

In addition to the final ‘polished’ version, many creators distribute editable source files of their content to make it easier for those who want to use the work for their own purposes. For example, in addition to the physical book or ebook, you might want to distribute files of a CC-licensed book that enable people to easily cut and paste the content into their own works.

DRM

Using a distribution platform that applies digital rights management (DRM) such as copy protection technology to your work is another way you can inadvertently make it very hard for reusers to make use of the permissions in the CC licence. If you have to upload your CC-licensed works to a platform that uses DRM, consider also distributing the same content on sites that do not use DRM.

Note that the CC licences prohibit you from applying DRM to someone else’s CC-licensed work without their permission.

Visibility

Earlier in the course we explored a range of places where you could find CC-licensed resources. You can also share your work on these platforms. Once you have selected the best places to share your work online, ensure you provide relevant information so that others can attribute your work correctly. If you have the opportunity to add metadata (often described as ‘data about data’) or tags when you are uploading a resource, this can also make it easier to find your work.

Final remarks

Sharing your content using Creative Commons licences is generous, but that alone isn’t enough to make it easy for others to reuse and adapt your work. Spend some time thinking from the perspective of someone who finds your shared content. How easy is it for them to download, reuse and/or revise it? Are there legal or technical obstacles that make it difficult for them to do the things that the CC licence is designed to allow?

Openness in education means more than just access or legal certainty over what you are can use, modify and share with your students. Open education means designing content and practices that ensure everyone can actively participate and contribute to the sum of all human knowledge. As educators and students revise others’ OER and create and share new OER, accessibility should always be on your design checklist.

5.3 Adapting and remixing CC-licensed works

Combining and adapting CC-licensed works is where things can get a little tricky. This lesson will give you the tools you need.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- describe the basics of what it means to create an adaptation or remix

- explain the scope of the ShareAlike and NoDerivatives clauses

- identify what licence compatibility means and how to determine whether licences are compatible.

Reflection

Have you ever wondered how to use CC-licensed work created by someone else in something you are creating? Have you ever come across CC-licensed work you wanted to reuse but were unsure about whether doing so would require you to apply a ShareAlike licence to what you created?

Introduction

The great promise of Creative Commons licensing is that it increases the pool of content from which we can draw to create new works. To take advantage of this potential, you have to understand when and how you can incorporate and adapt CC-licensed works. This requires careful attention to the particular CC licences that apply, as well as a working understanding of the legal concept of adaptations as a matter of copyright.

Being open enables educators to use the resource more effectively, which can lead to better learning and student outcomes. OER can be remixed and adapted, meaning that they can be updated, tailored and improved locally to fit the needs of students – for example, by:

- translating the OER into a local language

- adapting a biology open textbook to align it with local science standards

- modifying an OER simulation to make it accessible for a student who cannot hear.

The ideas of remix and adaptation are fundamental to education. Creative reuse of materials created by other educators and authors is about more than just seeking inspiration; we copy, adapt and combine different materials to craft education resources for our students.

Adapting OER

Copying a CC-licensed work and sharing it is straightforward. You must:

- make sure to provide attribution (TASL)

- refrain from using it for commercial purposes if it is licensed with one of the non-commercial (NC) licences.

If a CC licence permits – for example, if it does not contain the no-derivatives (ND) element – then you can also make changes to a resource and share it with others. In Section 5.1 we looked at doing this and how to acknowledge the changes, as well as introducing derivative works.

But incorporating materials created by others and combining materials from different sources can be tricky in terms of both pedagogy and copyright. What do we need to consider if we are changing a CC-licensed work or incorporating it into a new work?

First, remember that if your use of someone else’s CC-licensed work falls under an exception or limitation to copyright (such as fair use or fair dealing), then you have no obligations under the CC licence. If that is not the case, you need to rely on the CC licence for permission to adapt the work.

The threshold question then becomes: is what you are doing creating an adaptation?

Adaptation (or derivative work, as it is called in some parts of the world) is a term of art in copyright law. In Unit 1 we noted that the new Myanmar Copyright Act has not yet defined what is referred to as ‘adaptation’, although this type of work is covered by the new Act. In general, adaptation means creating something new from a copyrighted work that is sufficiently original to itself be protected by copyright. This is not always easy to determine, although some clear lines do exist. Under the new Myanmar Copyright Act, works that change format are considered adaptations and therefore require permission from the copyright holder. You can read more about what constitutes an adaptation in different countries in this explanation from Creative Commons. Some examples of adaptations include a film based on a novel or a translation of a book from one language into another.

Keep in mind that not all changes to a work result in the creation of an adaptation, such as spelling corrections. Also remember that to constitute an adaptation, the resulting work itself must be considered based on or derived from the original. This means that if you use a few lines from a poem to illustrate a poetry technique in an article you’re writing, your article is not an adaptation, because your article is not derived from or based on the poem from which you took a few lines. However, if you rearranged the stanzas in the poem and added new lines, then the resulting work would almost always be considered an adaptation.

As of version 4.0, all CC licences, even the ND or no-derivatives licences, allow anyone to make an adaptation of a CC-licensed work. The difference between the ND licences and the other licences is that if an adaptation of an ND-licensed work has been created, it cannot be shared with others. This allows, for example, an individual user to create adaptations of an ND-licensed work. But ND does not allow the individual to share adaptations with others, including to students at an educational institution.

If your reuse of a CC-licensed work does not create an adaptation, you should note the following points:

- You are not required to apply a licence with a ShareAlike (SA) element in it to your overall work if you are using an SA-licensed work within it. For example, you might be designing a presentation and want to use a CC BY-SA 4.0 photo to illustrate a slide. You are not going to adapt the photo; therefore, the ‘SA’ element of the licence does not impact on the licence type you should choose for your presentation, because the photo remains a discrete entity. We will return to look at this in more detail in our discussion of collections below.

- The ND restriction does not prevent you from using an ND-licensed work. This is because you are not adapting or creating derivatives from the work with an ND licence on it.

- You can combine CC-licensed material that you have not adapted with other work as long as you attribute and comply with the non-commercial (NC) restriction if it applies.

If your reuse of a CC-licensed work does create an adaptation, then there are limits on whether and how you may share the adapted work. We will look at those next. But first, a note about collections of materials.

Adaptations/remixes vs collections

The distinction between adaptations and collections is one of the trickiest concepts in copyright law. While there are many situations in which the differences are clear, there are also several ambiguous scenarios. The distinction between adaptations and remixes varies by jurisdiction and, even within a given jurisdiction, a judge’s determination between the two can be subjective, since there are few definitive rules on which to rely.

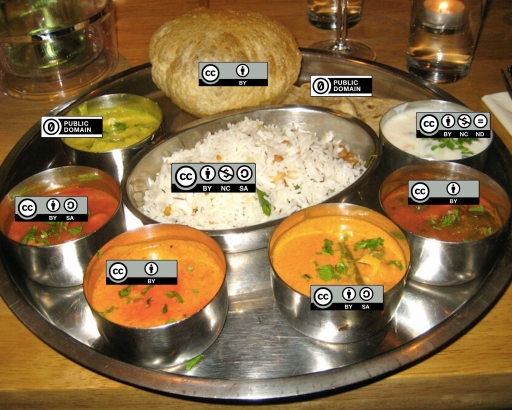

In contrast to an adaptation or remix, a collection involves the assembly of separate and independent creative works into a collective whole. A collection is not an adaptation. Let’s use the analogue of food and drink to take a closer look at the difference between adaptations/remixes and collections.

Adaptation or remix?

A remix is a type of adaptation that blends together a combination of resources from different sources to create a wholly new creation. As the resources have been combined together seamlessly, you often cannot tell where one openly licensed work ends and another begins. An example of a remix could be a new textbook that you create by combining several OER with your own material to create a new textbook. While this flexibility is useful for the new creator, it is still important to provide attribution to the individual parts that went into making the adaptation.

A good way to illustrate how remix works is the analogy of a ‘smoothie’ drink. In the picture above, you can see that the smoothie drink (CC BY-NC-SA) has been created by blending together bananas (CC BY NC), strawberries (public domain), oranges (CC BY NC-SA) and pineapple (CC BY).

There are some important things to consider before we make the smoothie. First, in order to combine these fruits to make the smoothie, they need to have compatible licence types. This is why it is important to plan ahead when you want to combine different openly licensed resources together.

Second, it’s important to be aware of what licences work well together. The table below reviews what open licences are compatible with each other for remix purposes. The table includes CC0 and public domain. You can choose one licence type on the vertical and another licence type on the horizontal.

- The tick symbol (✔) means that that one licence type is compatible with another licence type. This is good news if you would like to create a remix using OER with these licences.

- A cross symbol (✘) means that the licences selected are incompatible for remixing. This means you cannot remix OER with these licence types.

| Public domain ‘no known copyright’ | Public domain ‘no rights reserved’ | CC BY | CC BY-SA | CC BY-NC | CC BY-ND | CC BY-NC-SA | CC BY-NC-ND | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HighlightedPublic domain ‘no known copyright’ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ |

| Public domain ‘no rights reserved’ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | ✘ |

| HighlightedCC BY | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ |

| CC BY-SA | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ |

| HighlightedCC BY-NC | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ |

| CC BY-ND | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ |

| HighlightedCC BY-NC-SA | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ | Highlighted✔ | Highlighted✘ |

| CC BY-NC-ND | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ |

Footnotes

This Remix chart was reformatted as part of the OEPS course Becoming an open educator (Section 4.2, ‘Remixing OER’). The original table is from Frequently Asked Questions by Creative Commons and licensed CC BY 4.0Let’s look at an example. Say I would like to remix textbook content licensed CC BY-NC with online course content that is licensed CC BY-SA. Are these licence types compatible?

That’s correct! Unfortunately I would not be able to remix these OER. This is because if I use CC BY-SA licensed material in a remix, I cannot combine it with OER that additionally requires me to prohibit commercial use. To do so would be a violation of the requirements of the CC BY-SA licence.

However, you would not be able to combine CC BY-SA and CC BY-NC-SA resources together. This is because you would be unable to abide by the requirement to license the resource both CC BY-SA and CC BY-NC-SA.

Let’s return to the example of our smoothie drink, which is licensed CC BY-NC-SA. Let’s look at the types of licences used in this combination. The smoothie drink has been created from banana (CC BY NC), strawberries (public domain), oranges (CC BY NC-SA) and pineapple (CC BY). The most restrictive licence used in this remix is the oranges (CC BY NC-SA). Use the chart above to review what licences CC BY NC-SA is compatible with.

Yes, that’s correct! You cannot combine CC BY NC-SA licensed resources with CC BY-SA, CC BY-ND or CC BY-NC-ND licensed resources. This is because two of these licence types contain the no-derivatives (ND) element (CC BY-ND and CC BY-NC-ND) and so cannot be adapted and shared with others. The remaining licence type CC BY-SA requires us to license any adapted versions of the material on the same licence type. Because the oranges already have a ‘SA’ requirement that is different to that of the CC BY-SA licence, we cannot combine these works. This means that if we wanted to use the oranges in our smoothie drink, only fruits in the Public Domain or licensed CC BY, CC BY-NC or CC BY-NC-SA could be combined.

As you can see, it’s very important to consider different licence types and to ensure that they are compatible before you start to combine them to make something new. As we’ve seen above, remix is easier if you are combining open resources which use more liberal licences, such as CC BY. Although you cannot include copyrighted material in your OER without permission, you can provide URLs to copyrighted material: for example, videos on YouTube that are not openly licensed.

What should I do if the OER I have found cannot be remixed?

If you have OER that cannot be remixed together, you could:

- look for alternative OER

- contact the rights holder/creator of the resource to see if they would be happy for you to use the resource in a different way – this would need to be acknowledged appropriately.

How should I attribute adapted works?

In Unit 5.1 we saw the example of ‘90fied’, which had been created by adapting a photo that was originally licensed CC BY 2.0:

This work ‘90fied’ is a derivative of Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco by tvol used under CC BY 2.0. ‘90fied’ is licensed under [licence type] by [your name].

This section will take a closer look at what licences could be applied to both adaptations of individual OER (such as the ‘90fied’ image) and adaptations that blend together or remix a range of OER (such as the smoothie drink we saw earlier). What options do you have for licensing the copyright in your adaptations? The original licence(s) continue to govern reuse of the elements from the original work(s) that you used when creating your adaptation. Remember that your rights in your adaptation only apply to your own contributions.

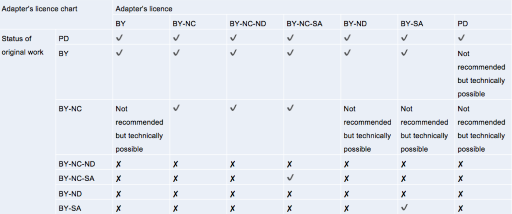

Let’s look at the Adapters Licence Chart below. The left-hand column of the chart shows the status of the original work. When using the chart, you will select the licence applied to the resource you have adapted. In instances where you have combined more than one resource (as in the case of the smoothie, above) you will have already used the Remix Chart above to ensure that you are not trying to combine resources that are incompatible. This means you should review the most restrictive licence in the remix to check how you can license the new resource you have created.

The top row of the table shows the different options for licensing your adaptation. In the main body of the table there are three possible responses to whether the ‘status of the original work’ or licence on the OER you would like to remix is compatible with the licence you would like to apply to your new remix:

- A tick symbol (✔) means that the status of the original work is compatible with your chosen licence type – this is good news if you would like to apply this licence to your adaptation!

- A cross symbol (✘) means that you cannot license your adaptation using that licence type. This is because your chosen licence type is not compatible with the licence that was originally applied to the OER.

- There is a small number of examples where you could apply a particular licence to your adaptation, but it is not advisable. These options are described as ‘Not recommended but technically possible’.

Let’s look at the chart in more detail:

You cannot change resources that include a NoDerivatives (ND) component in their licence. This means that if a resource is licensed CC BY-ND or CC BY-NC-ND, you cannot make changes to the resource and share it. This is why there are no licence options for these resources and a cross is shown for all possible adapter licence options.

For resources that include a ShareAlike (SA) component in the original licence, you must apply the same licence to your adapted resource. If the original resource was CC BY-SA, your new resource must also be licensed CC BY-SA. If the original resource was CC BY-NC-SA, you must also license your version of the resource CC BY-NC-SA. All SA licences after version 1.0 allow you to use a later version of the same licence on your adaptation.

The smoothie drink has been created from banana (CC BY NC), strawberries (public domain), oranges (CC BY NC-SA) and pineapple (CC BY). The most restrictive licence used in the remix is the oranges (CC BY NC-SA). As we saw in the last section, including oranges in our smoothie drink limits the different license types we can combine. In this instance, as we are including a resource with a ShareAlike (SA) license, this also determines the license that we can apply to the smoothie drink itself. The smoothie drink is therefore licensed CC BY NC-SA – the same license as the orange. This is because if you use material with a ShareAlike (SA) licence, you are required to apply that licence type to your remix.

There are also a small number of non-CC licences that have been designated as CC Compatible Licences for ShareAlike purposes. You can read more about that here.

There is a number of options for OER that you would like to adapt that are in the public domain or licensed CC BY or CC BY-NC.

What is in the public domain depends on the copyright law where you are. Public domain resources are no longer copyrighted. There are also resources marked with a CC0 licence, where creators have formally relinquished or given up their copyright before it expires. This means that the resource is now in the public domain.

With public domain or CC0 resources you also do not have to provide any information on the original creator (if available) when you reuse the resource. However, it is often useful to include this information (if available) with the URL so that other people can find the original. You can apply any CC licence to your new version of the CC0 or public domain resources.

There are a number of options for resources that are originally CC BY-NC and CC BY that are described as ‘not recommended but technically possible’. Why is this the case?

Applying a ‘not recommended but technically possible’ license to your remix or adaptation means you are not violating license requirements but you are potentially making it difficult for other users who want to use your resource. For example, if you changed a CC BY-NC licensed resource, applying a CC BY-NC, CC BY-NC-SA or CC BY-NC-ND licence to your new creation would clearly retain the original ‘NC’ aspect of the licence in each instance, even though the ‘SA’ and ‘ND’ versions would be more restrictive than the original license. This is why all these options are marked with a tick on the table. However, if you were to license a CC BY-NC resource as CC BY, CC BY-ND or CC BY-SA, it would not be clear to other users that the original resource should not be used in commercial contexts as per the Non-Commercial (NC) element requirement. Hence these options are all described as ‘not recommended but technically possible’.

You therefore need to ensure you include information about the original licence so that other users are aware of the original licence conditions. As Creative Commons notes:

CC does not recommend using a licence if the corresponding box is … [‘not recommended but technically possible’], although doing so is technically permitted by the terms of the licence. If you do, you should take additional care to mark the adaptation as involving multiple copyrights under different terms so that downstream users are aware of their obligations to comply with the licences from all rights holders. (Creative Commons, n.d.)

In the example of ‘90field’, the original image that this derivative is based on (Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco) is licensed CC BY. According to the Adapter’s License Chart, this means you could licence your new creation on any CC licence or dedicate it to the Public Domain by using the CC0 tool. However, it is not recommended to dedicate the work to the public domain, since there is no requirement to attribute this type of resource. This would mean that, as there is not requirement to attribute material in the Public Domain, it is likely that as the new creation was used and shared, information about the original resource (‘90fied’) would be lost.

As with any OER, you will need to acknowledge all resources appropriately and you should always provide attribution for all sources that were remixed. This can be done at the end of a chapter (if you are creating a textbook) or in a separate acknowledgements or sources list. We will look at some examples of these lists in the section on referencing below.

In the additional resources section you will find a range of resources on remixing, including more on attribution. You can also find the original Adapter’s Licence chart here.

Collections

Like a thali, a collection compiles different works together while keeping them organised as distinct separate objects. This means you are not blending OER together, as seen in the example of the smoothie, but keeping resources separate. This means that you can include NoDerivatives (ND) licensed resources and adapted material in a collection, because you are keeping each openly licensed resource separate. As we noted earlier, a collection is not an adaptation.

An example of a collection would be a book that compiles openly licensed essays from different sources together.

When you combine material into a collection, you may have a separate copyright of your own that you may license. However, your copyright only extends to the new contributions that you made to the work. In a collection, that is the selection and arrangement of the various works in the collection, and not the individual works themselves.

For example, you can select and arrange pre-existing poems published by others into an anthology, write an introduction, and design a cover for the collection, but your copyright and the only copyright you can license extends to your arrangement of the poems (not the poems themselves), as well as your original introduction and cover. The poems are not yours to license. You must also provide attribution and licensing information about the individual works in your collection. This gives the public the information they need to understand who created what and which license terms apply to specific content.

In the example of the thali above, there is a mix of differently licensed resources included in the collection: Public Domain, CC BY, CC BY-SA, CC BY-ND, CC BY-NC-SA and CC BY-NC-ND. What licence could we apply to this collection? Although we have included ND-licensed resources, it is important to note that these do not affect the overall licence of a collection. This is because in a collection, all resources remain discrete from each other. We might make changes to an individual resource that we include, but because it remains discrete, we will only acknowledge any changes we have made in relation to a specific piece of OER.

We also have both SA- and NC-licensed resources in the ‘thali’ collection. Because this is a collection rather than a remix, the SA restriction does not apply to how we license our collection – only to any adaptation we make of an individual, discrete resource.

However, if you incorporate non-commercial (NC) licensed material into a collection (as in the instance of the thali above), you cannot use the collection commercially and should make it clear to others that the collection should not be used commercially. This could be done in a number of different ways. For example, you could apply a Non-Commercial (NC) license to the collection. This would then clearly indicate to potential users that the collection should not be used commercially.

Alternatively, you might apply another license (e.g. CC BY) to your collection but clearly indicate that the collection contains Non-Commercial (NC) licensed resources. This could take the form of an addition to the attribution statement and disclaimer. Including this information upfront would make it very clear to users that your collection included material that could only be used in non-commercial contexts.

Let’s now take a closer look at how you should reference these types of resources.

Referencing

When you create a collection or remix OER, you must provide attribution for the individual works that you have used. This gives users of your OER the information they need to understand who created what and which licence terms apply to specific content. Your attributions should include the Title, Author, Source and Licence (TASL) for each of the OER you use.

As mentioned earlier, you can use an acknowledgements or sources section to organise this information. Using a disclaimer on the overall work also helps a user to understand what licence type has been applied to the overall work, but that there are exceptions. Let’s take a look at the different ways we can acknowledge OER use and when each is most appropriate.

Attributing a collection

Here are some examples of how you could attribute a collection. For example, you could have created a presentation or website that comprises your original content and openly licensed images. You could attribute each image on the relevant slide or where they are used online. Alternatively, depending on the resource, you could have the individual attributions listed on a separate slide of a presentation or on a separate page of a course.

In an appropriate place on the resource – such as the cover of a presentation or on the footer of a website – you could use one of the following statements, which would include a URL to the licence you are applying to your collection:

- [Name of resource] by [creator] is licensed [licence type], unless otherwise stated.

- Unless otherwise noted, [name of resource] by [creator] is licensed [licence type].

- This work was created by [creator] and is licensed under [licence type], unless otherwise stated.

In these three instances, you have either included all the TASL information required or you are providing an attribution within a context where it is clear what ‘this work’ is referring to. In addition, you have a disclaimer ‘unless otherwise stated’ or ‘unless otherwise noted’, which makes it clear to the user that there are exceptions and that resources with different license terms have been included.

If you don’t acknowledge individual pieces of OER as you use them (such as including an attribution next to a picture you use), you can list these in an acknowledgements or sources list. For example:

The example above shows the image and asset credits page for a course called Open Research 2014. The overall course is openly licensed (CC BY-SA 4.0). The course has a disclaimer similar to those listed above, acknowledging that it contains other OER.

The overall course licence applies to the original content created by the course authors (OER Hub). Openly licensed images used for the course are attributed separately.

Attributing a remix

When attributing a remix, you need to still ensure that you acknowledge every piece of OER that you have used, even though those OER may have been blended together to become indistinguishable from each other. For example, this course contains both remixed material and resources (such as images) that remain discrete. If you look at this course’s copyright and acknowledgements pages, you will see information on all the OER included in the course and a statement that acknowledges the course is a remix. When attributing a remix you have created you could use a similar statement. As you can see in the example below, this statement includes the disclaimer ‘unless otherwise stated’ to cover the inclusion of individual OER that are also used within the course.

‘[Name of new work]’ is an adaptation of [Name of work(s) you have remixed including URL to original resource(s)] published as of [date] (the ‘Original Work’), licensed by [name of creator(s) whose work you have adapted] under a [CC licence used on work(s) you have adapted and URL to these]. This adaptation is made and published by [your name] (the ‘Adapter’) under a [CC licence you have applied to your adapted work], unless otherwise stated.

The Adapter modified the Original Work in the following respects: [list of adaptations] (‘the Adapter Work’)

Your own practice

When creating OER or adapting material, you should always consider whether it is appropriate to apply a more restrictive licence to your work. Think about the photo ‘90fied’ from earlier in this unit. This adaptation was based on the photo ‘Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco’ which is licensed CC BY 2.0. When licensing the adaptation ‘90fied’ it is permitted to apply a more restrictive licence. However, is applying a restrictive licence in the spirit of openness or the original license? If we want to enable reuse in all contexts, where possible we should license our version of the resource CC BY too.

You also need to consider how easy it will be for someone to reuse your new version of a resource. To help others, avoid applying licences described as ‘not recommended but technically possible’ to OER you have adapted.

As we saw in Section 5.2, you should also consider making your resource available in different formats and on different platforms. This will enable people to reuse it more easily.

Final remarks

It can be intimidating to approach remix in a way that is consistent with copyright. In this unit we covered different ways of using OER and how to ensure that we attribute the OER we use appropriately.

Having the knowledge and skills to support the creation of adaptations and collections of OER at your university is critically important for librarians, ICT and support staff. In the next unit we will take a closer look at the role that OER and CC-licensed material could have at your university.