Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 2 May 2024, 12:42 PM

An overview of national AMR surveillance

Introduction

You should be familiar with the concept of

The emergence of resistance in bacteria is a natural evolutionary process. It becomes a problem when there is acceleration of this natural process as a consequence of the widespread, often inappropriate, use of

- assessment of the scale of the AMR problem, across human and animal sectors

- measurement of patterns of AMR over time in a particular place(s) and species

- development of appropriate public health policies and strategies to mitigate AMR across sectors

- planning and implementation of strategies, and assessment of their ongoing effectiveness in tackling AMR across and within sectors.

We touched on examples of national AMR surveillance systems and the components of such systems, as per the WHO GLASS framework, in the module Introducing AMR surveillance systems.

In this module, the focus will be on national AMR surveillance relevant to human health. The module AMR surveillance in animals will focus on AMR surveillance in the animal sector.

After completing this module, you will be able to:

- describe the structure, functions and characteristics of AMR surveillance systems in the context of the WHO GLASS approach

- know the components of national surveillance systems and how they contribute to AMR surveillance

- understand the governance structures needed for a functioning surveillance system, such as antimicrobial resistance coordinating committees, technical working groups and equivalent bodies

- understand the key stakeholders needed to establish, support and maintain such a system

- know how your role fits within local and national AMR surveillance systems.

Activity 1: Assessing your skills and knowledge

Please take a moment to think about the learning outcomes accompanying this module and how confident you feel about your knowledge and skills in these areas. Do not worry if you do not feel very confident in some skills; they may be areas that you are hoping to develop by studying this module. Now use the interactive tool to rate your confidence in the following areas using a 1–5 scale:

- 5 Very confident

- 4 Confident

- 3 Somewhat confident

- 2 Slightly confident

- 1 Not at all confident

Try to use the full range of ratings shown above to rate yourself.

1 WHO GLASS

In 2015, the

In the Early Implementation phase, the programme focused on clinical AMR data in humans only (GLASS-AMR), however, as the programme expands, additional modules, such as surveillance for emerging AMR (GLASS-EAR), One Health and AMC surveillance, are being piloted and added. GLASS is regularly reviewed and revised, and you can refer to the website for the most up-to-date information.

1.1 WHO GLASS objectives

‘The goal of GLASS is to enable standardised, comparable and validated data on AMR to be collected, analysed and shared with countries, in order to inform decision-making, drive local, national and regional action, and provide the evidence base for action and advocacy.’

As noted, GLASS promotes and supports a standardised approach to data collection, analysis and sharing by nations. It also provides a portal for submission of AMR data and produces an annual report on the results. As part of the standardised approach, GLASS provides guidance on the key components (i.e. the structure, processes and functions) of a national AMR surveillance system, so that data reported to GLASS are readily comparable between countries. It addresses issues around the use of common standards for methods, data sharing and coordination at local and national levels.

The objectives of GLASS are as follows:

- Fostering the development and maintenance of national AMR surveillance systems.

- Developing and maintaining global standards in AMR data collection, analysis and reporting.

- Helping countries develop frameworks linking local and national surveillance systems.

- Annually reporting AMR data, derived from nation-specific data.

- Estimating the burden of AMR.

- Detecting and alerting nations of the emergence of new mechanisms of resistance and their spread.

- Supporting the development of a quality assurance framework.

- Informing and evaluating public health strategies embedded in country

national action plans (NAPs) . - Assessing the impact of public health interventions to tackle AMR regularly.

2 The function of national AMR surveillance systems

The function of a national AMR surveillance system should incorporate the nine GLASS objectives as detailed above. As mentioned earlier, for the purposes of this module we will focus on human health and related issues. Not all countries will follow the GLASS format, but the principles are applicable to any similar surveillance system.

The GLASS initiative is designed to encourage the development of national AMR surveillance systems, with the WHO compiling data submitted at a national level into an annual report which allows international comparisons. Surveillance should primarily be a locally led activity. Recording and reporting AMR at the national level is an important part of a coherent and joined-up national strategy to tackle AMR.

We will now discuss the key features of national AMR surveillance systems, as recommended by WHO GLASS.

2.1 Focus on priority bacterial pathogens related to human health

GLASS recommends that national AMR surveillance activities should concentrate on antimicrobial-resistance in bacteria that cause common infections in humans. AMR surveillance cannot include all forms of resistance in all bacteria – so rare forms of resistance or infections are not typically included in routine surveillance activities. Pathogens currently included in GLASS-AMR are Acinetobacter spp., E. coli, K. pneumoniae, N. gonorrhoeae, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., S. aureus and S. pneumoniae. These pathogens have been identified as priorities for surveillance because they are common causes of severe disease and may frequently be multidrug resistant.

Breaking this down by sample type, GLASS collates results from blood culture samples on:

- Acinetobacter spp.

- E. coli

- K. pneumoniae

- Salmonella spp

- S. aureus

- S. pneumoniae

from urine samples on:

- E. coli

- K. pneumoniae

from stool samples on:

- Salmonella spp.

- Shigella spp.

and from cervical and urethral specimens on:

- N. gonorrhoeae

Section 4.4 expands on aspects of sampling.

National AMR surveillance systems are expected to collect, collate and share data according to sample type and corresponding bacterial species, aggregate the data at national level, and then report to WHO GLASS. Note that these data are normally obtained from patient samples sent to laboratories for routine clinical purposes, and also used for public health information purposes.

From your knowledge of previous modules, is this an example of active or passive surveillance?

This is a form of passive surveillance, as described in previous modules, with sampling performed as part of routine clinical investigations for patients presenting with infection. GLASS collates this national data under the remit of GLASS-AMR routine data surveillance.

2.2 Antimicrobial consumption data related to human health

In the module Introducing AMR surveillance systems, you were introduced to the concept of

Can you recall the definition of AMC?

AMC is defined in terms of the ‘sale’ of antimicrobial medicines.

The ‘sale’ of antimicrobials is captured by way of national-level estimates of the quantities of antimicrobials imported and manufactured. These estimates are mainly derived from import, sales or reimbursement databases. Such data can serve as proxy for actual use of antibiotics, for which data collection is often more difficult. AMC data is typically expressed in terms of a

GLASS, via its GLASS-AMC routine data surveillance activity, launched in 2019, asks national AMR surveillance systems to submit AMC data aggregated at national level. AMC data requirements centre around lists of registered antimicrobial medicines, the quantity of antimicrobials used and related contextual information. When countries submit AMC data to GLASS, the WHO then gives feedback of comparison of the levels of consumption of antimicrobials against other countries.

AMC data analyses at national level should aid the understanding of the trends and amount of antimicrobials used nationally. Overall use of particular antimicrobials within a country is a major driver of the local level of resistance to that agent, though some drugs may be used predominantly within one or other sectors. AMC data therefore gives useful information on what amount of evolutionary pressure is being exerted by the use of these antimicrobials within the country. Such analyses help drive national policies, strategies and interventions to optimise the use of antimicrobials.

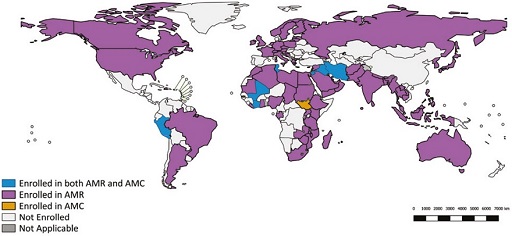

National AMR surveillance systems are able to benefit from this unified approach to mitigating AMR by way of participating (sharing data) with GLASS-AMR and GLASS-AMC, respectively. Figure 1 shows a map of countries (as of 2020) enrolled in GLASS-AMR and/or GLASS-AMC.

Now that you’ve reacquainted yourself with the concept of AMC and why monitoring trends in antimicrobial consumption is important, please take a moment to answer the following question.

Does improper and widespread use of antibiotics diminish, increase, undermine or prevent the rate of antibiotic resistance?

Improper and widespread use of antibiotics increases the rate of antibiotic resistance.

3 The structure of national AMR surveillance systems

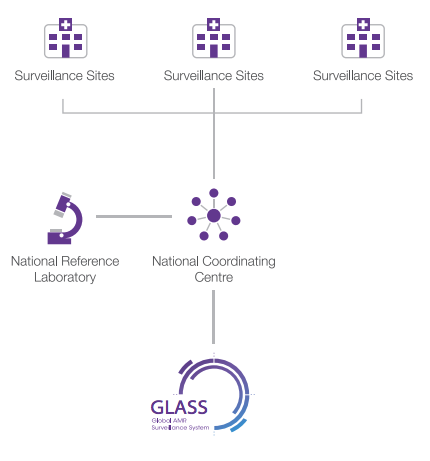

WHO GLASS-AMR recommends that national AMR surveillance systems have three core components, as illustrated in Figure 2, namely:

national coordinating centre (NCC) national reference laboratory (NRL) - selected AMR surveillance sites.

Let’s discuss these three components in detail.

3.1 National coordinating centre

A key component that ensures the functioning of a national AMR surveillance system is the setting up of a national coordinating centre or NCC. The NCC oversees the functioning of the national AMR surveillance system. The NCC is required to carry out the following actions:

- Coordinate the collection and aggregation of AMR data from surveillance sites and national reference laboratories.

- Analyse and share this AMR data with WHO GLASS.

- Define AMR objectives at a national level, linked to the national AMR strategy.

- Monitor the national surveillance system and ensure its correct functioning.

- Offer epidemiological, laboratory and management expertise to facilitate the implementation of the WHO GLASS standards.

- Be the central point of communication with national policy makers and the WHO.

As noted in Section 2, the WHO GLASS-led initiative is designed to encourage nations to develop national AMR surveillance systems. Surveillance is primarily a locally led activity. As discussed in the module Introducing AMR surveillance systems, many countries have existing surveillance systems. Where possible, an existing national public health institute is nominated as an NCC. The NCC should support a One Health approach, by communicating regularly with counterparts from other sectors (in many countries each sector has their own NCC), and continue to review the scope of AMR surveillance, as the capacity and capability of the national AMR surveillance system evolves.

The NCC is usually a subcommittee or technical working group (TWG) of the AMRCC (AMR coordinating committee) or similar body (see Section 5.6).

Activity 2: National coordinating centres

3.2 National reference laboratory

The second component of a national AMR surveillance system is a national reference laboratory or NRL. The function of the NRL is to promote good microbiology laboratory practice by compiling and disseminating standard methods (maintaining quality standards) to participating surveillance sites. It may also perform confirmatory testing, for example, to confirm new or unusual resistance patterns, and support surveillance sites by providing training.

Different sectors may have their own national reference laboratories; for example, in the UK, the national reference laboratory for healthcare-associated bacteria is the AMR and Healthcare Associated Infections (AMRHAI) laboratory, while the National Reference Laboratory for Food Microbiology monitors AMR in food, and the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) is responsible for AMR surveillance activities in animals. The NRL(s) and NCC should work together to maintain a standardised approach to reporting and verifying laboratory results.

3.3 Surveillance sites

Surveillance site designation is managed by the NCC. There is no specified number of surveillance sites that need to be recruited prior to commencing AMR data submission to WHO GLASS. However, countries are expected to have at least one surveillance site (which might be an appropriate total in a small nation or if very limited resources are available), with epidemiological and laboratory expertise, and infrastructure for the collection of clinical, microbiological and demographic data from patients. A larger country or a country with more resources will have a larger number of surveillance sites, within the scope of the funding available.

Surveillance sites are usually hospitals or outpatient health facilities with access to relevant laboratory support. Surveillance sites should be selected for having a balanced geographical, demographic and socio-economic distribution in terms of their patient population. This allows for data gathered at these sites to be representative of the nation’s whole population. Ideally, surveillance sites should be chosen to give the best possible representation of geography, demographics and level of healthcare. In practice, surveillance sites may be chosen for more pragmatic reasons, such as already having a well-functioning microbiology laboratory or good transport links with the NRL.

3.4 National systems in action

Let us look at two examples of a national AMR surveillance system incorporating these components, in alignment with the WHO GLASS framework. We will consider two examples of German national AMR surveillance systems: one gathering data on bacterial antimicrobial

- The Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance monitoring system (or ARS, in German) was established in 2007 by the Robert Koch Institute, the national public health institute of Germany. It gathers data centrally and evaluates resistance trends in the outpatient and inpatient settings. The surveillance system covers all clinically indicated samples submitted, the bacterial pathogens isolated and the antimicrobial susceptibility test results. The ARS invites submissions from medical laboratories that process samples from patients in medical facilities. Resistance statistics based on this data are then made accessible via an interactive dashboard. The platform is supported by multiple agencies including the National Antibiotics Committee and National Reference Centres. The National Reference Centres have an advisory function and deal with:

- developing and improving diagnostic methods for pathogens

- examining trends in resistance development

- publishing frequent reports on the epidemiology of AMR.

European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) and WHO GLASS. - Alongside Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Monitoring System (ARS), the Robert Koch Institute set up the Antimicrobial Consumption Surveillance (AVS, in German) to support hospitals carrying out AMC surveillance. It gathers AMC data from 397 hospitals and rehabilitation facilities.

Germany is currently trialling a system called ARVIA, an integrated antimicrobial resistance and consumption monitoring project, which aims to combine AMR and AMC surveillance data at national level from ARS and AVS, respectively.

Activity 3: National systems in action

4 Factors affecting local and national surveillance operations

Local surveillance sites collect, collate and submit AMR data to the NCC, who analyse these data at the national level and may also submit data to WHO GLASS. Hospitals make for ideal AMR surveillance sites, owing to the volume of patient samples routinely processed, the availability of epidemiological and laboratory expertise on site, and the existence of a framework for laboratory processing and documentation of samples that aid clinical decision making. For all these reasons, AMR surveillance sites are almost always set up to operate within existing hospitals.

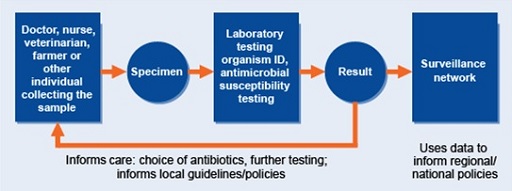

Surveillance sites rely on their own local AMR data collection systems. Figure 3 is a good representation of how local AMR data collection systems should look and how they link to national AMR surveillance systems.

Let us now discuss the key considerations for the effective functioning of a national AMR surveillance system. The responsibility for ensuring that these considerations are applied lies both with the local surveillance sites and with the NCC at the national level.

4.1 Representativeness

GLASS recognises that most patient-level data are derived from hospital-based surveillance sites. As hospitals process many or most of their samples from hospital inpatients, samples from inpatients are often over-represented in the AMR surveillance data – this can lead to the assumption that AMR levels are higher than they actually are in the whole population. As national AMR surveillance systems mature (which happens over many years), there is an expectation that the choice of surveillance sites should expand to include outpatient healthcare facilities, for example, general practices, renal dialysis units (which often see the same cohort of patients regularly) and nursing homes. This allows for community AMR trend monitoring. Diversity or representativeness of AMR data is key, as it ensures that policy decisions, strategies and interventions developed at national level are based on data from the widest possible population. Surveillance sites should ensure consistency in procedures for sample collection and reporting to the national AMR surveillance system.

4.2 Population estimation

In order to estimate the prevalence of resistance in pathogens carried by a given population, ideally national AMR surveillance systems should collect data to describe the populations from whom the data are obtained. An estimation of surveillance coverage is then made, allowing GLASS to accurately report on trends in AMR prevalence over time at national level. WHO GLASS asks for the following population data to be submitted by national AMR surveillance systems, which in turn requires the following relevant data collection at the surveillance sites:

- The total national population (typically from census data).

- Number of patients seeking care over a 12-month period at the healthcare facilities operating as surveillance sites in the country (typically from hospital administrative records).

- Number of patients with positive and negative cultures categorised by specimen type (from laboratory records).

- Number of susceptible and non-susceptible pathogens for each priority pathogen–antimicrobial, categorised by specimen type, stratified according to core demographic data e.g. by age (from laboratory and hospital records).

- Length of admission at the healthcare facility. The length of admission to hospital is useful for AMR surveillance purposes as it gives an indication as to whether an infection was

community-acquired orhospital-acquired . Community-acquired and hospital-acquired antimicrobial resistant infections require different types of public health intervention, so it is useful to be able to distinguish them in surveillance data (from laboratory and hospital records).

4.3 Epidemiology and laboratory expertise

Epidemiological and laboratory expertise of surveillance site personnel is key to ensuring that good quality data is submitted to the national AMR surveillance system and then onwards to WHO GLASS. WHO advocates that surveillance sites have adequate access to epidemiological expertise, by way of trained personnel competent in collecting, analysing and reporting AMR data, and laboratory expertise, which can utilise on-site laboratory infrastructure to test specimens and report them in accordance with GLASS guidelines (WHO, 2016).

4.4 Standardisation of antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) data reporting

WHO GLASS recommends that pathogen data should include sampling type and bacterial species details, in line with guidance laid out in the GLASS manual (WHO, 2015b). Susceptibility data are derived from

Activity 4: Designing a surveillance system

In Section 3, we examined examples of national AMR surveillance systems in Germany, namely the ARS and AVS. We also discussed ARVIA, the system being trialled with the aim of combining AMR and AMC data from ARS and AVS, respectively.

Taking into account what you have learnt in Section 4, what considerations would you apply when designing a system such as ARVIA?

Hint – if you were designing such a system, would ‘representativeness’ be a valid consideration? How about ensuring ‘standardisation of AST reporting’? If so, why? Write down which considerations would apply and a few points explaining why you think so.

Answer

Representativeness – should be addressed by ensuring that AMR and AMC data are gathered from a variety of surveillance sites, and that both are collected in most sites to enable further interpretation (e.g. explore the association between consumption and resistance data).

Standardisation of AST – reporting should be addressed by ensuring surveillance sites report susceptibility data in a consistent manner, according to EUCAST or CLSI methodology, and following similar SOPs.

Other considerations:

Population estimation – Information on population makeup, for example, demographics and geographic spread, needs to be considered to ensure accurate measurement of AMR and AMC.

Epidemiology and laboratory expertise – ARVIA would rely on the expertise of bodies designated as NRLs (in this example, Robert Koch Institute).

We have discussed areas that require work on the part of local surveillance sites. We will now discuss what samples are included in the national surveillance system using this framework. Note that this is also covered in the Sampling modules.

4.5 Sample collection

GLASS advocates a tiered approach to AMR surveillance. Countries start with the highest priority clinically relevant pathogens in available sample types to establish their AMR surveillance systems. Over time, further bacterial species that are of clinical importance for surveillance are identified, either from the same or additional sample types. In time, results from laboratory testing of these additional pathogens can be included in the established routine AMR surveillance.

Local clinical practice at surveillance sites determines the type of clinical samples (blood, urine, faeces, etc.) sent to the laboratory. Ideally speaking, clinical practice should be standardised according to guidelines and recognised standards, such as those from international infectious disease organisations. For example, best practice guidelines recommend that all patients presenting to hospital with symptoms of a urinary tract infection should have a urine sample taken. This may not be routine clinical practice in countries where resources for microbiology testing are limited and/or patients might have to pay for individual laboratory tests.

When reporting data to the NCC, the following information should be included for each sample: sample type, AST results and patient information, including demographics and epidemiological features.

Table 1 provides details of specimen (sample) types and the corresponding pathogens prioritised for AMR surveillance by WHO GLASS. The specimen types represent infections in the bloodstream, gastrointestinal tract and genitourinary/reproductive tract. These infections are common all around the world, so resistance in pathogens which cause them is of high concern.

Reporting for AMR surveillance focuses on eight WHO priority pathogens, namely Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp. and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Countries can also include any other pathogens of local or national importance.

| Specimen | Laboratory case definition | Surveillance type and sampling setting | Priority pathogens for surveillance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Isolation of pathogen from blood Footnotes a | Selected sites or national coverage Continuous Patients in hospital and in the community | E. coli K. pneumoniae A. baumannii S. aureus S. pneumoniae Salmonella spp. |

Urine | Significant growth in urine specimen Footnotes b | Selected sites or national coverage Continuous Patients in hospital and in the community | E. coli K. pneumoniae |

Faeces | Isolation of Salmonella spp. Footnotes c or Shigella spp. from stools | Selected sites or national coverage Continuous Patients in hospital and in the community | Salmonella spp. Shigella spp. |

Urethral and cervical swabs | Isolation of N. gonorrhoeae | Selected sites or national coverage Continuous Patients in hospital and in the community | N. gonorrhoeae |

Footnotes

Footnotes aAny pathogen isolated from a blood culture may be significant for surveillance locally and nationally; only the prioritised pathogens for global surveillance are listed here. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes bPure culture according to local laboratory practice. Catheter samples should be excluded if possible. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes cDiarrhoeal surveillance is for non-typhoid salmonella species; for local clinical purposes, typhoid and paratyphoid should be included. Back to main textBlood samples are the single highest-priority specimen type for AMR surveillance. A positive blood culture sample points to a pathogen having a severe and life-threatening impact on the patient concerned. However, the collecting of blood samples is not an easy process from clinical and laboratory perspectives.

As discussed in Section 4.4, AST results provide information on the degree to which pathogens are susceptible to antimicrobials routinely used to treat them. WHO recommend that countries collect the AST data for specific pathogen-antimicrobial combinations; these are based on the most concerning resistance profiles emerging worldwide. Countries report each pathogen as susceptible (S), intermediate (I) or resistant (R) to the antimicrobials of interest. AST results corresponding to each antimicrobial can be classified as susceptible (S), intermediate (I), resistant (R), not tested or not applicable. The module Antimicrobial susceptibility testing discusses this in detail. Table 2 provides details on pathogen-antimicrobial combinations as per WHO GLASS.

| Pathogen | Antibacterial class | Antibacterial agents that may be used for ASTa,b |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Sulfonamides and trimethoprim | Co-trimoxazole |

Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin | |

Third-generation cephalosporins | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime and ceftazidime | |

Fourth-generation cephalosporins | Cefepime | |

Carbapenems Footnotes c | Imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem or doripenem | |

Polymyxins | Colistin | |

Penicillins | Ampicillin | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Sulfonamides and trimethoprim | Co-trimoxazole |

Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin | |

Third-generation cephalosporins | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime and ceftazidime | |

Fourth-generation cephalosporins | Cefepime | |

Carbapenems Footnotes c | Imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem or doripenem | |

Polymyxins | Colistin | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Tetracyclines | Tigecycline or minocycline |

Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin and amikacin | |

Carbapenems Footnotes c | Imipenem, meropenem or doripenem | |

Polymyxins | Colistin | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Penicillinase-stable beta-lactams | Cefoxitin Footnotes d |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Penicillins | Oxacillin Footnotes e Penicillin G |

Sufonamides and trimethoprim | Co-trimoxazole | |

Third-generation cephalosporins | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime | |

| Salmonella spp. | Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin |

Third-generation cephalosporins | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime and ceftazidime | |

Carbapenems Footnotes c | Imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem or doripenem | |

| Shigella spp. | Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin |

Third-generation cephalosporins | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime and ceftazidime | |

Macrolides | Azithromycin | |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Third-generation cephalosporins | Cefixime Ceftriaxone |

Macrolides | Azithromycin | |

Aminocyclitols | Spectinomycin | |

Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin | |

Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin |

Footnotes

Footnotes aThe listed substances are priorities for surveillance of resistance in each pathogen, although they may not be first-line options for treatment. One or more of the drugs listed may be tested.Footnotes

Footnotes bOne or more of the drugs listed may be tested in countries. S, I, R and nominator and denominator data for each shall be reported separately.Footnotes

Footnotes cImipenem or meropenem is preferred to represent the group when available.Footnotes

Footnotes dCefoxitin is a surrogate for testing susceptibility to oxacillin (methicillin, nafcillin); the AST report to clinicians should state susceptibility or resistance to oxacillin.Footnotes

Footnotes eOxacillin is a surrogate for testing reduced susceptibility or resistance to penicillin; the AST report to clinicians should state reduced susceptibility or resistance to penicillin.Activity 5: Sample collection

5 Frameworks underpinning the development of national action plans on AMR

WHO’s

Country NAPs must outline the national strategic vision, aligned to that set out in the GAP-AMR, preferably with a national AMR surveillance system, collecting and analysing local surveillance site data. The development framework for these is laid out in the GAP-AMR (WHO, 2015a) and in the manual for developing NAPs, a resolution drafted as part of the 68th World Health Assembly in May 2015.

AMR NAPs should be linked to key public health strategic objectives, one of which is ‘Objective 2: Strengthen the knowledge and evidence base through surveillance and research’ (WHO, 2015a). AMR NAPs usually contain multiple objectives, not just conducting AMR surveillance. For example, other typical objectives include reducing transmission of resistant infections through improved infection prevention and control, and conducting research on novel antimicrobials.

The development framework specific to ‘Objective 2’ underlines the importance of the establishment of a national AMR surveillance system by country. It outlines the ‘measures of effectiveness’ of strategies carried out by individual countries. One measure of effectiveness relevant to this discussion is defined as follows: ‘Extent of reduction in the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance, based on data collected through integrated programmes for surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in all countries.’ (WHO, 2015a).

WHO recommends an incremental approach to the development of NAPs. When embarking on developing or refining their NAPs, countries should consider:

- stakeholder engagement

- available resources

- the state of current practice and policies specific to AMR and AMC.

Other considerations include the development and evaluation of plans to ensure the establishment of:

- frameworks for collaboration at local, national and international levels

- national laboratory and epidemiology capacity

- current national data on AMR and AMC

- governance structures

- frameworks incorporating legal and ethical concerns

- frameworks for internal and external quality assessment

- case definitions.

We will cover each of these in detail in the following sections.

First, let us discuss the relevant stakeholders, vital to the ongoing development and assessment of NAPs, with specific emphasis on objective 2, the effective functioning of national AMR surveillance systems.

5.1 Stakeholders

A successful AMR surveillance programme requires political support and strong engagement from the governmental body responsible for Public Health. The positioning of a national AMR programme alongside a governmental Public Health body reflects the national importance of AMR and policies designed to mitigate it.

Other important organisations include:

- national governmental bodies e.g. national doctors’ union, national pharmacy body

- national research agencies

- political parties, to make sure AMR remains high on the national agenda, and benefits from cross party agreement

- global health donors

- international development institutions

- international research-funding organisations

- aid and technical agencies.

These institutions should support countries in building capacity for collecting and analysing data on prevalence of AMR and facilitate the sharing and reporting of such data.

5.2 Governance structures

Well-designed governance structures, which include expert authorities, ensure the robustness of NAPs and national interventions, such as the development of surveillance systems. They also allow for transparency and oversight at all stages of NAP development and implementation.

According to the One Health agenda, outlined in the GAP-AMR, the following stakeholder involvement should be considered to ensure appropriate oversight: i) representation from human, animal, food safety, agricultural, and environmental sectors; ii) local focal points, such as those in the academic health and hospital sectors, and competent nominated laboratories, acting as surveillance sites; and iii) technical groups, comprising experts in governance, surveillance, quality assessment, and legal and ethical implications. The roles and responsibilities of the above should be well-defined. Assessment and recruitment of the membership of these bodies should be conducted on an ongoing basis, with consideration of NAP creation, development and evaluation.

5.3 Assessment of existing infrastructure

Countries are likely to be at different stages of development and implementation of their AMR NAPs. An assessment of existing policies, activities, surveillance systems, and local and national cross-sector collaborative frameworks is an essential step in understanding the local context of AMR surveillance. An assessment of this kind is also likely to be the first step needed when initiating plans for an AMR surveillance system, so that technical working groups and stakeholders can get an overview of the current status of AMR and AMC in a given country. A checklist of activities can then follow, based on the GAP-AMR framework, prioritising any discrepancies identified in the country’s assessment. These can then be incorporated into a NAP.

This assessment will also assist in the selection of NCC, NRL and surveillance sites (see Section 3), together making up a functional national AMR surveillance system. Utilising and/or building on, wherever possible, existing expertise allows national AMR surveillance systems to rapidly develop the ability to systematically collect the relevant information.

5.4 Quality assurance

In an AMR surveillance system, the NCC is tasked with the responsibility of monitoring quality assurance. The work itself is headed by the responsible technical team or technical working group (TWG). The technical team, in liaison with external stakeholders, should ensure standardisation of all processes relating to AMR surveillance across local surveillance sites and at national level. Promotion of standardisation is achieved by providing training by the NCC’s technical teams to laboratory staff and by facilitating the development of internal quality assurance standards at surveillance site laboratories.

Maintaining quality standards includes ensuring that data on isolates (including patient characteristics), AST and population statistics (as detailed in Sections 4.2–4.5) are captured in a standard format by surveillance sites. This extends to core laboratory processes, including isolate identification, susceptibility testing and storage. Quality standard frameworks should be applied at every stage of data handling and manipulation, and, ideally, should involve automated data validity checks, ensuring consistency, completeness and accuracy of data gathered. Quality assurance will be covered further in the module Quality assurance and AMR surveillance.

Quality assurance is a vital part of running an AMR surveillance system. If the AMR information being collected at the local level is not of a high standard and consistency, the eventual output of the whole surveillance system will be unreliable.

5.5 Legal and ethical considerations in line with established practices for global disease surveillance and reporting

The legal justification for using individual level data without consent by public health surveillance programmes relies on the concept that poorer health outcomes will occur in the population if such surveillance structures do not exist. Thus, public health programmes including national AMR surveillance systems are legally mandated by national governments based on the notion of a public good, and are in line with the government’s responsibility to ensure public health and safety.

National AMR surveillance systems require data, often from multiple local surveillance sites, to be shared with national level surveillance structures. This requirement to collate data from multiple sources (often at patient level from local hospital sites) necessitates a sound legal and ethical governance framework. Such frameworks outlining best practice for data collection, sharing, storage and reporting should be built on individual countries’ existing data confidentiality laws, after discussion with appropriate stakeholders.

Different countries have developed their own NAPs to support integrated surveillance and reporting of antimicrobial resistance and consumption.

You can learn more about legal and ethical issues in the Legal and ethical considerations in AMR data module.

5.6 The role of the AMR coordination committee (AMRCC)

Part of the remit of the governance structures is the setting up of the

The WHO definition of the role of AMRCC is to ‘oversee and, when necessary, to coordinate AMR-related activities in all sectors to ensure a systematic, comprehensive approach’. Figure 4 outlines the responsibilities of AMRCCs.

The implementation of NAPs and, by extension, national AMR surveillance systems, is dependent on the availability of resources, extent of cross sectoral collaboration and political will. This makes implementing NAPs difficult in resource-limited settings of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). AMRCCs carry out their responsibility by understanding which AMR activities need to be focused on. The following allow AMRCCs to carry out their function:

- AMRCCs are established with clarity of the roles and responsibilities of those who comprise them.

- The ability exists to adapt and scale up the present AMR surveillance infrastructure, rather than build a new one, which is a resource-heavy process.

- Governance structures are set up, that include stakeholders from government, academia and professional bodies, making cross-sector support for implementing strategies more likely.

The national coordinating centre for AMR surveillance is often a technical working group under the AMRCC. Depending on the country, there may be no separate surveillance NCC, in which case its functions should be fulfilled by the AMRCC.

5.7 Point prevalence surveys for AMU

One of the factors that drives AMR is the overprescribing and injudicious use of antimicrobials. Even though antimicrobial resistance is a natural phenomenon, the rate of spread of AMR and the associated burden of morbidity and mortality can be minimised by controlling the inappropriate use of antimicrobials. Thus, one of the key objectives of the WHO GAP-AMR is to curtail the inappropriate use of antimicrobials. The first step is to understand the national and global picture of antibiotic consumption. As discussed in previous sections, national AMR surveillance systems are tasked with collecting data on both AMR and AMC. Additional data on how antimicrobials are used (antimicrobial use, AMU) completes the picture, by determining whether drugs are being used appropriately. This is important because high levels of consumption may simply reflect a higher burden of infectious diseases and simply trying to reduce consumption without understanding the actual use of antimicrobials may result in adverse effects on health.

One method for collecting information on AMU in the healthcare setting is to use a

The WHO have developed a methodology for PPS, which collects basic information from hospitalised patients’ medical records, with the aim of collecting baseline information on the use of antimicrobials. This process can then be repeated at set time intervals to provide a trend of antimicrobial use.

When PPSs are carried out to gain an understanding of AMU at national level, they must adopt a multicentre survey methodology. This sees a national coordinator leading the survey in multiple selected hospitals countrywide. Numbers surveyed and patient demographic composition are important as they reflect the representativeness of antimicrobial consumption data. The WHO protocol considers the following when conducting PPSs:

- selecting the type of hospital(s) for inclusion

- distinguishing between hospital wards that should and should not be included

- identifying a category of patients to include

- selecting the type of antimicrobials to include

- sampling methodology.

The WHO PPS methodology is an adaptation of several other protocols, including the Global PPS project from University of Antwerp and the Medicines Utilisation Research in Africa (MURIA) project. In some countries it may be preferable to use these protocols if they have been used for previous surveys or if the expertise needed for the WHO methodology is lacking.

A typical recommendation is that a PPS should be repeated every one to two years, however, the methodology can also be adapted for more regular, focused, stewardship audits, such as for follow-up surveys to assess the effects of specific interventions.

5.8 Reflecting on your role

Activity 6: Does your country submit data to GLASS?

If your country is enrolled with GLASS and has a national AMR surveillance system for human health, you should be able see your GLASS country profile (WHO, 2017) by selecting it from the ‘Select Country’ drop-down menu on the right-hand side of the page. Don’t worry if your country doesn’t appear; try to find a country that is nearest to yours in size and income level.

Jot down key details from your country’s profile, such as:

- What information does your country submit to GLASS?

- Which sample types?

- Which pathogens?

If your country isn’t enrolled with GLASS, jot down key steps you think the government, national agencies, local agencies and public policy departments can take to enable this transition.

- What other considerations do you think can be highlighted?

- Is there a framework outlining any of these e.g. legal, ethical, governance?

Activity 7: Reflecting on your country’s national action plan

The WHO website details country AMR-NAPs. (Open the quiz in a new tab or window by holding down ‘Ctrl’ (or ‘Cmd’ on a Mac) when you click on the link.)

Find your country’s NAP (if one has been published) and answer the following questions:

- What does your country NAP say about the data the national AMR surveillance system reports on? Are both AMR and AMC data reported, or only one of the two?

- Can you identify the NCC, NRL and surveillance sites in your country?

- How many surveillance sites have enrolled? Are they hospitals, outpatient centres, or both?

Record your findings in the note box.

Note, try using the search function on your computer or look at the contents page of the report to find the information you need.

Hint - see the German or Indian examples given in the activity in Section 3.4.

6 End-of-module quiz

Well done – you have reached the end of this module and can now do the quiz to test your learning.

This quiz is an opportunity for you to reflect on what you have learned rather than a test, and you can revisit it as many times as you like.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window by holding down ‘Ctrl’ (or ‘Cmd’ on a Mac) when you click on the quiz.

7 Summary

In this module, you have learnt about national AMR surveillance systems and reflected on the frameworks and considerations that make up these systems.

You should now be able to outline and describe:

- national AMR surveillance systems in the context of the WHO GLASS approach

- core components of an ideal national surveillance system: national coordinating centres (NCCs), national reference laboratories (NRLs) and surveillance sites

- GAP AMR, national actions plans (NAPs) and development of national surveillance strategies

- structures of a national surveillance system, such as antimicrobial resistance coordinating committees (AMRCCs), technical working groups, and similar bodies

- key stakeholders needed to establish, support and maintain a national surveillance system

- factors affecting local and national surveillance networks

- your role within your local AMR surveillance system.

Now that you have completed this module, consider the following questions:

- What is the single most important lesson that you have taken away from this module?

- How relevant is it to your work?

- Can you suggest ways in which this new knowledge can benefit your practice?

When you have reflected on these, go to your reflective blog and note down your thoughts.

Activity 8: Reflecting on your progress

Do you remember at the beginning of this module you were asked to take a moment to think about these learning outcomes and how confident you felt about your knowledge and skills in these areas?

Now that you have completed this module, take some time to reflect on your progress and use the interactive tool to rate your confidence in these areas using the following scale:

- 5 Very confident

- 4 Confident

- 3 Neither confident nor not confident

- 2 Not very confident

- 1 Not at all confident

Try to use the full range of ratings shown above to rate yourself:

When you have reflected on your answers and your progress on this module, go to your reflective blog and note down your thoughts.

8 Your experience of this module

Now that you have completed this module, take a few moments to reflect on your experience of working through it. Please complete a survey to tell us about your reflections. Your responses will allow us to gauge how useful you have found this module and how effectively you have engaged with the content. We will also use your feedback on this pathway to better inform the design of future online experiences for our learners.

Many thanks for your help.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was collaboratively written by Siddharth Mookerjee and Patrick Murphy, and reviewed by Alexander Aiken, Claire Gordon, Natalie Moyen and Hilary MacQueen.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

Module image: madpixblue/123RF.

Figure 1: Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) Report, Early Implementation, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. Available online at https://apps.who.int/ iris/ bitstream/ handle/ 10665/ 332081/ 9789240005587-eng.pdf?ua=1.

Figure 2: reproduced from National Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Systems and Participation in the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS), copyright 2016 World Health Organization. Available online at https://apps.who.int/ iris/ bitstream/ handle/ 10665/ 251554/ WHO-DGO-AMR-2016.4-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Figure 3: The Open University.

Figure 4: adapted (colour change) from Figure 2 of Typical Responsibilities of an AMR Coordinating Committee in Turning Plans into Action for Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) ¬ Working Paper 2.0: Implementation and Coordination, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019 (WHO/WSI/AMR/2019.2). This file is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO), https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-nc-sa/ 3.0/ igo.

Tables

Tables 1 and 2: reproduced from Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System: Manual for Early Implementation, p. 5, copyright 2015 World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/ antimicrobial-resistance/ publications/ surveillance-system-manual/ en/.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.