1.1 Origins of samples

Clinical samples come from a range of different settings, such as:

- secondary and tertiary care patients in hospital

- community patients seen in clinics

- specialist community clinics and outpatient departments, for example tuberculosis (

TB ) or sexual health services.

Activity 2: Types of sample

Make notes on the types of samples that are sent to your microbiology laboratory. Compare your response with the sample answer.

Discussion

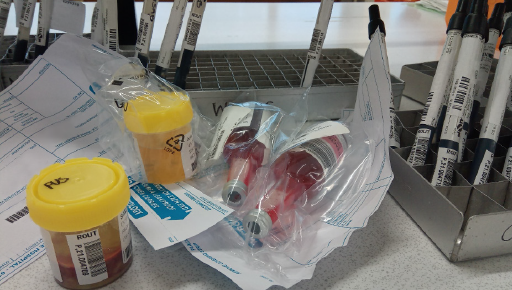

Microbiology samples include the following:

- Swabs, for example from wounds, throats, eyes and ears

- Genital (cervical and urethral) samples

- Urine

- Blood

- Other normally sterile fluids, such as cerebrospinal fluid (

CSF ), synovial fluid - Stools

- Sputum – for TB and sometimes other respiratory pathogens

- Pus and tissue from sterile and non-sterile sites.

Clinical samples are generally sent to microbiology laboratories to guide antimicrobial therapy (Figure 1). This is done by identifying which pathogens are present in the sample by culturing them. These pathogens can then additionally be tested for antimicrobial resistance (

-

What factors can prompt the sending of samples?

-

Factors that trigger a request for microbiological tests on a sample include the following:

- The physician wants to determine if infection is present.

- Standard antibiotics are not working (treatment failure).

- A very severe or unusual infection.

- Local policies or guidelines on sampling.

- Financial or other external incentives. For example, if a contract means the physician or healthcare organisation gets paid more if extra samples are sent, more are likely to be analysed, some perhaps unnecessarily, leading to a waste of resources. Ideally, the decision to send a sample is made without financial considerations in mind.

- Local culture or peer pressure, since people are likely to send, or not send, samples for testing according to what their colleagues are doing.

-

What factors can deter the sending of samples, even if clinically necessary?

-

Factors that can deter physicians from sending clinical samples for testing include:

- difficulty in accessing a laboratory, perhaps due to logistical or transport problems

- a lack of equipment to obtain samples, for example sterile swabs or blood culture bottles

- a lack of trust in laboratory test results

- turnaround times which are too long to be useful

- cost pressures, for example the patient cannot afford the test or there is only a small or no budget available for testing

- no local culture of doing tests

- not understanding the benefits of testing.

Clinical specimens are also routinely used as a source of data for AMR surveillance. However, a significant proportion of patients who could have a microbiology test performed never get sampled and so no results are available for them. This introduces an element of bias into the data. As a consequence, more severe cases and treatment failures could be over-represented. Tertiary care cases could also have more samples sent than those in more remote settings which could affect the overall results if resistance patterns differ between the settings. For long term, sustainable AMR surveillance, however, it is much cheaper and simpler to use clinical samples and the associated data than establishing a study to sample more randomly. The data are also always available whereas a surveillance study might be a one-off event.

Whilst it is not possible to avoid all potential bias when using clinical samples for surveillance purposes, it helps to be aware that reported rates of AMR may not be representative of the country or region as a whole.

1 Principles of sampling and specimen collection