Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 14 February 2026, 11:40 PM

3 Understanding autism

3 Understanding autism

In this section, you will explore the following areas:

3.1 What is autism?

The word 'spectrum'

The word ‘spectrum’ emphasises the variation amongst autistic people, with individuals having a unique pattern of strengths and difficulties. People on the autism spectrum have a range of intellectual abilities and will present differently depending on their developmental stage and sex. People on the autism spectrum will have a range of strengths and challenges and some will require a high level of need for support, while others will have more subtle difficulties that may still require support. People on the autism spectrum will also have individual differences in the range of their strengths and talents.

The definition of autism

Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental difference. This means it is a condition that affects the development of the brain. Autism affects the way a person communicates and interacts with others, how information is processed and how the person makes sense of the world.

The human population is highly diverse. Within the autistic population, there is also a great deal of diversity, and autism manifests differently from person to person.

For children and young people, there is a reciprocal relationship between the autistic learner and the environment – this includes the physical environment and the people around them. With appropriate understanding and adjustments, autistic people can flourish.

Autism is not a linear scale running from 'high functioning' to 'low functioning', which are unhelpful terms. Instead, autism varies in several different ways – sensory differences, levels of anxiety, social skills and executive functions all vary both from person to person and from time to time. Look at this short comic strip that provides one explanation of autism. A printable PDF version of the comic strip is available through the link.

Prevalence of autism

Autism affects around 1.03% of the Scottish population (McKay et al., 2018).

There are some groups where autism is under-recognised, for example:

- females

- black and minority ethnic children and young people

- children and young people living in poverty

- children and young people who are referred for autism assessments, because they have similar presentations, and do not receive a diagnosis of autism. However, they are still entitled to and require their needs to be met.

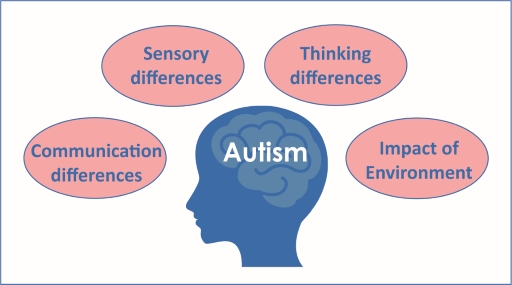

What is core to autism?

There are four characteristics core to autism:

- communication differences

- sensory differences

- thinking difference

- impact of environment.

When the above four aspects illustrated in Figure 9 are not supported appropriately, it will lead to increased anxiety for the autistic person, which is further discussed in Section 3.7.

What causes autism?

For most individuals, the cause of autism is not identified. Autism is generally thought to have a genetic basis and research is ongoing.

The Professional Development section on the Toolbox has a range of films you can watch which focus on the causes of autism.

Autism: males and females

Autism is thought to be more common in boys than girls. However, there is a growing consensus that girls are under-diagnosed or misdiagnosed. A range of reasons are given for this, including different societal expectations; diagnostic tools being designed around boys; and special interests are often gender determined due to social expectations, so interests of girls might be perceived as less unusual (e.g. strong interest in lip balms compared with interest in trains).

The quiet, anxious presentation of autism occurs across genders but might be more prevalent in girls, and these individuals are more likely to be missed.

The Professional Development section on the Toolbox has a range of films you can watch that focus on girls and autism.

3.2 Cognitive theories – overview

There are a number of theories that can help us to understand the ways autistic learners might experience the world and respond in the way that they do. These theories overlap and are not mutually exclusive. They can give us clues as to how to adapt what we do to support an autistic learner. It is important to remember, however, that autistic learners are individuals and like the population as a whole will have different degrees of strengths and difficulties with the behaviours outlined in the theories below.

Activity 6

Click and reveal the headings to find out more about each theory.

Theory of mind

Answer

- develops from joint attention

- involves understanding other people's thoughts, feelings, beliefs and experiences

- being able to take this understanding into account in your own actions.

Weak executive function

The ability to:

Answer

- plan, organise and sequence thoughts and actions

- control our impulses.

Weak central coherence

Answer

- the tendency to focus on details, rather than the 'big picture'

- this focus affects the person's ability to consider context.

Context blindness

Answer

- challenge in processing or using all of the information from visual, auditory, historical and social contexts to make sense of experiences in the moment

- missing the 'obvious'.

Double empathy problem

Answer

A mutual challenge of misunderstanding intentions, motivations or communication between autistic and non-autistic people.

Monotropism

Answer

A tendency to focus attention on one thing at a time, with difficulty shifting attention and processing multiple stimuli which might support understanding.

3.3 Communication and autism

‘Communication happens when one person sends a message to another person. This can be verbally or non-verbally. Interaction happens when two people respond to one another – two-way communication.’

Autism rarely occurs in isolation and commonly co-occurs with a range of speech, language and communication support needs. This can affect:

- non-verbal communication

- comprehension or understanding of other people’s communication

- expressive language

- social communication.

In order to support autistic learners and those with related needs in early learning centres and schools, it is essential that those around them understand their communication stage across these four areas of communication. One of the biggest causes of ‘distressed behaviour’ in this group is a mismatch between the individual’s capacity for communication and the way others around them do or do not adapt.

Speech and Language Therapists can provide expert assessment, training, coaching and advice around communication. However, all those involved with the child on a day-to-day basis at school and at home support success with two-way communication.

Communication can be pre-intentional and intentional

Pre-intentional

Where the learner says or acts without intending to affect those around them. This type of communication can be a reaction to something or can be used to self-sooth.

Intentional

Where the learner says or acts with the purpose of sending a message to another person. This type of communication can be used to ask for something or to object.

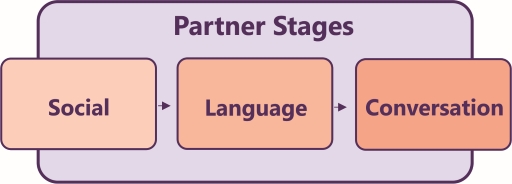

Communication stages

There are many ways we can think about stages of speech, language and communication development, and sources of detailed information about this. In the Toolbox, the following three stages (as described in the SCERTS model, Prizant et al, 2006) might be useful ways to think about the strategies we use and how they fit the child’s stage.

Pre-verbal or social partner stage

Individuals have less than ten words. Communication may be through behaviour and actions rather than words. Joint attention with others may be difficult, with attention focused on objects of interest. The individual may be communicating intentionally but may not. They may have some words, but these are not used consistently or effectively.

Language partner stage

At this stage individuals may have developed over 100 words, which they use with meaning. They may put words together in short phrases or sentences. Often at this stage they are able to talk best about the ‘here and now’ and find it harder to talk about the past or future. They may be able to say what they like and don’t like and, although they can learn emotion vocabulary, their theory of mind is at an early stage. They understand symbols and benefit from visual supports to support verbal communication.

Conversation partner stage

Conversation partners can engage in conversations with others. First, at a simple level, and then over time they can become sophisticated communicators. At this stage they can have an excellent vocabulary and mastery of language. They are likely to still need visual supports appropriate to their stage, and they may be able to use language or ‘meta-cognitive’ skills to overtly learn strategies to manage the social world. They may become able to mask some of their social communication difficulties and what we might notice are signs of anxiety or difficulties with social aspects of communication. The way we understand and use social communication develops over our lives and we should not underestimate the significant impact of social communication challenges for individuals at this stage.

Variability

When anxious or stressed, individuals do not understand and communicate in the way they do when calm and well regulated. We need to make bigger adaptations in reducing language and reducing expectations. It is recognised that communication skills observed can be ‘deceptive’ and people around them may judge that the person’s communication is at a higher stage than it is. For example, they may have good vocabulary around topics that interest them but have gaps in common vocabulary, or they may use echolalia, where they repeat words or phrases heard elsewhere.

Social communication

Social communication occurs between people and involves understanding of social signals and using social signals in more or less expected ways. It can require coordination of verbal and non-verbal messages.

Social communication differences are present in autistic individuals. These are lifelong but present in different ways at different stages.

For autistic learners, this can lead to feeling misunderstood or as if they are getting things ‘wrong’. Adults might notice unexpected behaviours in social situations. Peer relationships are often most successful with small groups or individuals with shared interests.

Eye contact

Reduced use or understanding of eye gaze for social purposes is core to autism. Some children will be overtly avoidant and seem to almost find direct gaze painful, whilst others will not have obvious outward difficulty with eye gaze. You do not have to have poor eye contact to be diagnosed with autism.

Joint attention

Typical children develop joint attention in the first year of life and by 9–18 months start to use pointing, with coordinated eye gaze, to both request and share attention as if saying ‘look at that’. They can have sophisticated communication turns with others with or without words because they know where other people are looking and that others have seen where they look.

A common early sign of autism is delay or absence of pointing to share attention by 18 months.

Joint attention is a precursor to social play and theory of mind. Older autistic learners may have developed simple joint attention but still have difficulty working out what others are focused on, interested in, what they feel or believe through joint attention, and interpreting other people’s non-verbal behaviour.

Prosody and American accents

We convey a range of meaning with our intonation, pitch and stress. For example, the phrase ‘cup of tea’ could be a question, a refusal, could indicate pleasure, an acceptance, a comment etc.

Autistic learners can have difficulties understanding prosody and therefore the intention behind the way teachers or peers say things, which in turn leads to social difficulties.

It is more common in autism than in other conditions for UK speakers to speak with an American accent. It is thought that they may give equal weight to language and intonation heard on TV as they do to that of their social world and family. Other children are likely to unconsciously give preference to the accent of their family over those with whom they have no social connection.

Body language

Autistic people may have difficulty processing or interpreting facial expressions, gestures and body language of others and therefore they miss social cues communicated in this way. They may not know they are being spoken to unless the other person uses their name first.

They may not notice body language at all because their attention is not focused on that. They may understand it in some contexts, in pictures or in discussion, but have difficulty interpreting it ‘in the moment’ or in context.

They may not notice body language at all because their attention is not focused on that. They may understand it in some contexts, in pictures or in discussion, but have difficulty interpreting it ‘in the moment’ or in context.

Prosopagnosia

Although not present in all autistic people, some may have a co-occurring difficulty with recognising people’s faces, judging ages or gender – including family members and close friends or even their own face. They may use alternative strategies, such as remembering clothes or places people are commonly seen. They may appear to be ignoring people and find it hard to use names correctly.

Autistic people may have difficulty processing or interpreting facial expressions, gestures and body language of others and therefore they miss social cues communicated in this way. They may not know they are being spoken to unless the other person uses their name first.

They may not notice body language at all, because their attention is not focused on that. They may understand it in some contexts, in pictures or in discussion, but have difficulty interpreting it ‘in the moment’ or in context.

While signing can be helpful as part of a ‘Total Communication’ approach, use of signing can be difficult for individuals who have difficulty with joint attention or noticing other people’s actions. For these individuals, objects, symbols or picture exchange systems can be more effective as communication supports.

Some autistic people may also use facial expressions and body language in an unexpected or idiosyncratic way, for example, smiling when anxious.

Comprehension or understanding of other people’s communication

It is common for understanding of autistic people to be overestimated. Although, we do see a range of stages, from not understanding words to having excellent language skills. Below are some examples of how the understanding of autistic individuals can be affected.

- Understanding varies with context and demands at any one time.

- Expressive language may be in advance of comprehension.

- Echolalia (repeating words or phrases immediately or after a delay) is often a sign of poor comprehension. Even when individuals are conversation partners, they can be ‘overliteral’ in their understanding and not pick up when people say one thing but mean another.

- The combined challenge with understanding non-verbal information, social information, unspoken and spoken messages means that the risk of misunderstanding is common.

3.4 Supporting communication

Key strategies

- reduce your language

- use the person’s name to cue them in

- focus on teaching the names of key people

- provide opportunities for initiation

- use visual supports

- allow time … wait

Individualised, stage-specific strategies and supports can be discussed with the team around the child.

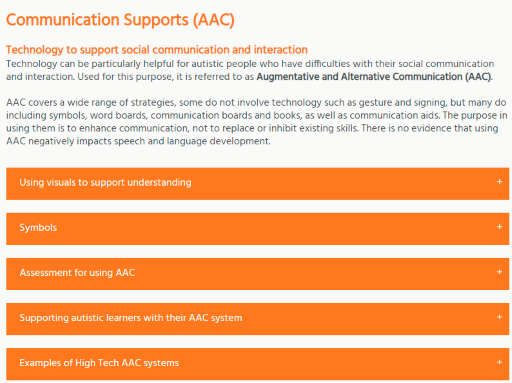

Technology to support social communication and interaction

Technology can be particularly helpful for autistic people who have difficulties with their social communication and interaction. Used for this purpose, it is referred to as Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC).

AAC covers a wide range of strategies: some do not involve technology such as gesture and signing, but many do, including symbols, word boards, communication boards and books, as well as communication aids. The purpose in using them is to enhance communication, not to replace or inhibit existing skills. There is no evidence that using AAC negatively impacts speech and language development.

Many AAC strategies are visual and relatively static. Spoken language, on the other hand, is auditory and always transitory by nature. Some people process information better when they are looking at pictures or written words to help them visualise spoken information.

Visual supports for communication often take the form of picture symbol sets used through pointing by those in the environment to supplement their speech. As well as supporting understanding, this also provides a model to the individual on how they can use symbols to get a message across. This teaching technique is often referred to as Aided Language Stimulation.

Autistic learners can benefit from the use of symbols in their environment and within their AAC system, whether printed (low tech) or electronic (high tech).

There is a range of picture symbol sets and software for printing visuals, including:

- Boardmaker using Picture Communication Symbols (PCS)

- Matrix Maker Plus which uses Widgit symbols, SymbolStix and Inclusive Technology symbols.

Low-tech AAC systems

It is important to consider the use of low-tech AAC systems, which include:

- pen and paper to write messages or draw

- alphabet and word boards

- communication charts or books with pictures, photos and symbols.

Some low-tech systems have been designed primarily for use by autistic learners. These include:

Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) – designed to teach autistic learners the basic concept of communication. At its core is the shaping and developing of communication activity, encouraging the individual to give a symbol to another person. That person giving the desired object in return

Pragmatic Organisation Dynamic Display (PODD) – an approach that involves giving individuals access to a large vocabulary of words in a symbol communication book, based on the way that we use language socially and taught through modelling. It is also available in some communication devices and apps.

The Toolbox has additional information and downloadable resources to support communication as highlighted in Figure 10.

Activity 7

- Go to the Communication Supports page on the Toolbox for further information on:

- using visual supports to support understanding

- symbols

- assessment for using AAC

- supporting autistic learners with the AAC system

- examples of high-tech AAC systems.

- Watch the short introduction film.

Autistic people and their families told us that the big five things that they wanted the public to understand were that autistic people can:

- need extra time to process information

- experience anxiety in social situations

- experience anxiety with unexpected changes

- find noise, smells and bright lights painful and distressing

- become overwhelmed and experience a 'meltdown' or 'shutdown'.

All of these areas will have an impact on being able to effectively communicate.

Expressive language

At least 50% of autistic people have a co-occurring developmental language disorder which can affect their speech, language and communication.

- Language can be measured in the words we use (vocabulary) and the way we put these together (grammar) and length of utterance.

- Expressive language may include echolalia (repeating words and phrases from people, TV or computers) or spontaneous and creative speech.

- Verbal dyspraxia affects the fluent articulation of speech, due to difficulties with planning motor movements for speech.

- Language can be expressed through words, pictures or signs.

Social communication

Difficulty understanding and using social communication according to the conventions of the local context affects individuals across the lifespan. This is not something that can be ‘fixed’. Social communication skills do develop and can be scaffolded, however, as individuals transition to new roles and activities in life, additional support might be required at each stage.

Some difficulties may be more apparent, such as those who talk repetitively or endlessly about a favourite topic. Others may be more subtle, such as those who ‘copy’ social behaviours or very rarely initiate and wait for other to take the lead in social interactions.

Metacognition

At the conversation partner stage, children begin to develop the ability to reflect upon their knowledge, learning and actions. Prior to this stage social skills, groups are not recommended (see NAIT Guidance on Social Communication Groups).

Peers

Peer interaction is often harder than interaction with those older and younger. Adults are likely to make adaptations and younger children’s communication is likely to be less sophisticated and demanding.

Groups can be more difficult than 1:1 interaction and therefore collaborative learning can present challenges. Reasonable adjustments may include:

- allocation of clear roles

- scripts

- sticking to familiar rather than new activities in groups

- having a familiar and supportive peer

- having predictability

- a range of visual supports

- at the secondary stage, individuals with good language skills and motivation to make friends might benefit from taking part in focused work on this (e.g. the PEERS programme).

Masking and camouflaging

Some autistic people use masking and camouflage as coping strategies. These may be intentional or unconscious habits (‘Putting on My Best Normal’: Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions, Hull et al., 2017).

Activity 8

In your Reflective Log, consider and note down how social communication differences may impact on an autistic learner’s educational activities and interactions.

Here are some examples.

Differences in social communication might affect the ability to:

Answer

- respond to group instructions

- take turns appropriately in group discussion

- understand ‘implied’ meanings, affecting aspects of literacy

- process information and respond within expected time

- organise several instructions given together

- remember or follow information or instructions given verbally.

Some autistic learners may have delayed language, but the degree of impairment varies greatly. Some may remain non-verbal throughout their life; others may have limited skills, only using speech to communicate their needs.

Supporting communication – key strategies

- reduce your language

- use the person’s name, to cue them in

- focus on teaching the names of key people

- provide opportunities for initiation

- use visual supports

- allow time … wait

- individualised, stage-specific strategies and supports can be discussed with the team around the child.

3.5 Environment

The environment can make a lot of demands on autistic learners. Using the CIRCLE collaboration approach, the Toolbox and this module focuses on three main focus areas when exploring the environment:

- physical

- social

- routines.

Physical environment

The physical environment consists of the sounds, smells, lighting, layout and visual aesthetic of a space and can all have an impact. It is important that reasonable adjustments are made to the classroom environment to reduce as many barriers to learning as possible. As with any child or young person, barriers will differ depending on the individual. Any adaptations can often benefit all learners in the classroom, not just the autistic learner.

The structure and ethos of the classroom are important tools for helping autistic learners understand expectations and access the curriculum. All learning environments should provide a positive influence and clear structure for autistic learners. This encourages independence and helps reduce anxiety. A well-organised, calm, supportive classroom with clear structure and routines can help make the environment a more predictable and accessible place, reducing distraction and confusion. This can include regular breaks throughout the day with access to different activities, some of which are multisensory. Where possible, practitioners should create physical structure, either using furniture or even tape or a mark on the floor. They should make the function and any accompanying rules of each area as clear as possible. They should carefully consider the seating arrangements in the classroom. Autistic learners may benefit from access to a quieter, distraction-free area in the class. The movement of other pupils as well as staff within the layout of the class is another aspect to consider, particularly where several staff members may work within the room.

Consideration of visuals within the classroom space is important. Busy displays and posters can be very distracting to an autistic learner. As a general rule, practitioners should aim for a clutter-free, low-stimulus environment. A well-organised classroom with stored items, equipment and books in clearly labelled cupboards/areas will promote independence as well as reducing distraction. The use of visual supports, at an appropriate developmental level, is expected for autistic learners. As with all supports, these should be regularly reviewed.

Social environment

The social environment is concerned with the attitudes, expectations and actions of those within the class and how these can affect autistic learners, either positively or negatively.

Practitioners should aim to develop a classroom culture where autistic learners feel valued and secure, individual differences are respected, and diversity is highlighted and celebrated. These children and young people learn best when they can focus on a task and are not anxious or worried. Practitioners should reduce stress by considering each learner’s competence. When children and young people have difficulty with retaining information, understanding instructions or the complexities of language used, practitioners should differentiate their own language and instructions, as a routine part of their practice e.g. say less, slow down your rate of speech, stress key words and use visuals to support understanding. Using a variety of teaching styles and allowing additional thinking/processing time can be valuable.

Routines

Routines are events that happen in the same way with regularity. The start, middle and end of the routine becomes predictable through repetition. Daily routines help autistic learners to know and anticipate what comes next, and social routines help them enjoy and interact with others. Autistic learners benefit from a degree of order and consistency in their lives. It may be useful to consider routines in terms of how the day/week is structured and how lessons are delivered.

Autistic learners may need developmentally appropriate visual support to help them recognise predictable routines and additional visual supports to help them understand changes to these routines. Having a consistent format for the start, middle and end of each lesson can be beneficial. Preparing learners for change, for example, giving clear notification (preferably communicated visually) if another member of staff will be covering the class, can be very beneficial. Simple approaches such as having consistent seating plans can help reduce the risk of anxiety or distraction and setting regular days for giving out and collecting homework can help learners develop good habits for completing it.

Practitioners should consider using a consistent format to lesson delivery, which can help autistic learners know what to expect, so that they can be prepared. Stating the learning intentions at the start of the lesson, ensuring that these are understood and referring to them regularly may help learners at conversation partner stage to focus. Reviewing and summarising learning outcomes may help these autistic learners understand if their personal learning targets have been achieved. Practitioners should encourage autistic learners to see themselves as respected and useful members of the class. This can be promoted by regularly assigning positive roles e.g. group leader or peer supporter. This can help reduce negative views that some autistic learners may have of themselves.

3.6 Sensory differences

Sensations are the foundations for learning and actions. Differences in sensory processing can profoundly affect skills and abilities in daily life, play and learning. Autistic learners and children with neurodevelopmental differences may process and experience sensation differently in unique and sometimes complex ways. For example, they may be:

- Very sensitive and may avoid, be unable to ignore or become overwhelmed by sensations, sometimes to extremes where they ‘shut down’, show extreme anger, fear and/or attempt to escape (sometimes referred to as ‘fight, fright or flight, adrenaline-fuelled reactions’).

- Very sensitive to some things, but do not show this, or strongly seek other sensations to block out ‘unpleasant’ sensations, reduce anxiety and feel calmer.

- Under-sensitive and may not register or react to even very powerful sensations. Can seem quite passive and slow to respond to sensations.

- Under-sensitive and may seek intense input from one or many senses.

(Based on the work of Winnie Dunn)

Every person with intact sensory organs constantly receives registers and processes information from their senses. The five most recognised senses are:

- sight

- hearing

- taste

- smell

- touch.

However, it is helpful to think about at least three more senses:

- Body position or proprioception – a sense of where the parts of our body are in relation to each other and the surroundings. Our brains work this out using information from our muscles, joints, along with the sensation of touching things e.g. the ground.

- Movement or vestibular sense – lets us know if we are moving, and, if so, in what direction and how fast. Information for this mostly comes from balance organs deep inside our ears.

- Internal body sense or interoception – a wide range of information is sent to our brain about hunger and thirst, when we have eaten and drunk enough, any pain or illness, body temperature, if we need to sleep, use the toilet, etc. Our internal body sense also includes the changes in heart rate, breathing, alertness and feelings like ‘butterflies’ or a sinking feeling (often in our gut), which come with and signal strong emotions.

Examples of what we might see:

Children may cover their ears or eyes, retreat, or become intensely upset. This can happen when the classroom, lunch hall or playground gets busy, or ‘simply’ because they expect or think they detect a disliked sound, smell, taste, sight, or when an internal sensation becomes unbearable. They may feel the need to rock, flap, chew, jump, run, hide, be squeezed or hugged, make their own sounds, or focus on one thing to help themselves feel better. If they can, they may learn to supress these feelings, but suppression has costs and there will still be signs they are struggling such as avoiding being near others, difficulty seeing objects or text, staying on task, etc. It is worth noting that they will react differently and cope more or less well depending on prior events.

Children might seem 'tuned out' or 'dazed', slumping in their seat, or lying down. They may not notice obstacles, how much force they are using, if they are in a mess, hurt or hurting others. They may seek prolonged intense movement, including banging, chewing or hitting hard, spinning or swinging. They may have an irresistible fascination and urge to touch, smell, taste, chew, hear or see something. Some children may learn and try to do this more subtly – reading, watching videos or persisting in talking about the sensations they seek.

It is extremely important to understand that these 'behaviours' are not intended to upset, challenge or provoke others. Fundamentally, they are signals that a child is trying to keep calm and cope with internal and external sensations that may be extremely and overwhelmingly unpleasant.

Activity 9

- Watch this film where an occupational therapist talks about the impact of sensory differences on everyday life and school experience.

3.7 Supporting autistic learners in an educational setting

Inclusive learning environments

Learning environments and adapting learning environments to specific needs. Creating an inclusive learning environment through positive relationships and behaviour is the responsibility of everyone in each community of learning. This approach will improve the support for autistic learners and their families as awareness of autism inclusion, wellbeing and equality is embedded across the school community. Information and professional learning on inclusive practice can be shared at:

- parental/carer information sessions

- staff information sessions

- blogs

- setting up and leading a collegiate/network group

- linking with the schools in your management group/cluster/family group/local area

- engaging with the development of school policies

- school websites

- providing professional development sessions at in-service events.

Inclusive classrooms

'The Inclusive classroom is fundamental to inclusion and the core of best teaching practice'.

Inclusive classrooms support all learners and reduce the extent to which further additional support is required and allows the implementation of individual support to be minimally intrusive. Developing an inclusive classroom therefore is a child-centred approach which meets professional and legislative duties. It is also an effective use of time management. For example:

- Ensuring appropriate labelling and visual supports are in the classroom supports learners who experience language and communication difficulties, and also English as an additional language.

- Effective planning and organisation will save time and support learners.

- Liaising with support colleagues and, if appropriate, ensuring effective management of any resources and their support staff time.

What makes a classroom feel inclusive to autistic learners?

Answer

- When each autistic learner is an individual and is included in developing their inclusive classroom.

- When the classroom routines are accessible e.g. use of visual supports.

- When we provide anticipatory supports.

- When we simplify communication.

- When the ethos of the school and classroom is one that values difference and expects diversity.

- When we incorporate the special interests of autistic learners into the lesson.

- When we provide planned movement breaks.

- When we take account of sensory preferences.

- When we implement the use of an individual safe space.

- When we agree a method to support a ‘Time in our safe space’. Discuss how this is worded.

- When we use emotional regulation approaches.

- When we ensure the whole class has an opportunity to explore diversity and equality.

- When we incorporate the special interests of autistic learners into the lesson.

- When we reduce sensory overload.

- When we create a quiet area in the room.

- When we prepare learners for unexpected change.

- Making reasonable adjustments to all aspects of school life e.g. curriculum materials, class routines and assessment arrangements.

Collaborative support

In partnership with families, colleagues and, where possible, the learner, find out what’s desirable and regulating, then build it into a day that is as routine or predictable as possible for your autistic learners.

Activity 10

In your Reflective Log, note down how you can find out this information as soon as possible, ideally before the learner joins your class/setting.

Here are some examples.

Answer

- Speak to parents, carers, whoever seems to really know and understand the child. Perhaps ask them to fill out a sensory checklist.

- Find out what supportive strategies and accommodations have been working recently.

- Get to know the child – If they are not yet using words (social partner), you will have to rely on others' reports, then watch their reactions very carefully as you 'test' what might work. If they have a few words (language partner), or more than 100 words (conversation partner), they may still need photos, symbols, objects or at very least, written choices, to communicate.

- Consider your whole school environment. How can you reasonably adjust the classrooms, corridors, gym hall, lunch areas, playground, toilets, etc.? For example, can you switch off noisy air-con or hand dryers or muffle bells? If not, can the child have headphones? Can we make their working space any better with partitions, less clutter, etc.? Which toilet feels easier to use? Where are they comfortable eating lunch?

- Think through a typical day at school. Would it be helpful for them to arrive before or after others? Or to come in through a quieter door or corridor? Should they have a calming activity before joining the group? Would it be helpful for them to leave classes early to avoid rush and crush?

- Communicate their timetable in a way they can understand. Do they need symbols, photos?

- Teach them to use their individual safe space where they can choose to go to without asking and can stay as long as they feel they need to.

How to use a safe space

Simply creating the space is not enough. Learners need to be taught how and when to go to the safe space in a calm moment, and they need to learn to trust that adults will use it in a consistent way.

You will need to download this file.

Download the NAIT Safe Space Guidance.

Other adjustments that can help

- Own choice of clothing, which still looks 'uniform'.

- A locker or safe place for things that help them calm down; pocket sized items that help concentration or are calming, sometimes called 'fidget objects'.

- Regular timetabled physical activity or 'movement breaks' (even when they seem calm – it’s 'fuel for their tank!').

- Regulation 'menu' (photos, symbols or a written list of chosen regulating activities).

- Visual supports for regulation such as zones of regulation materials.

- Discuss helping the child’s peers understand that some people have sensory differences. It may help to teach how to support or react to unconventional behaviours like a child’s need to ‘stim’ or the likelihood of upset outbursts.

In conclusion

Support is a marathon, not a sprint. Once you have got strategies in place, keep going. Review regularly, but ideally make changes in tandem with those who know the child or young person best, and make sure you pass what you have learned on to those who support the child. It is extremely important to share this to support any transition – macro or micro.

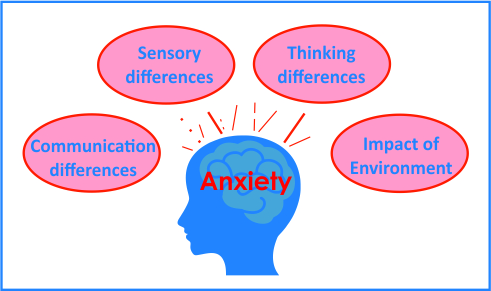

3.8 Autism and anxiety

Everyone experiences anxiety at points in their life, usually in response to difficult or stressful situations. When such situations pass, anxiety usually reduces over time. Anxiety becomes problematic when it impacts on everyday life and gets in the way of the person’s everyday functioning, seems disproportionate to the situation or continues for a long time.

When the above four aspects illustrated in Figure 11 are not supported appropriately, this will lead to increased anxiety for the autistic person.

Prior to the unprecedented Covid-19 pandemic, we knew that people with autism experience anxiety more than the general population. In 2017, a review of a number of studies found that children with autism spectrum disorder had higher anxiety levels than typically developing peers: this difference increased with cognitive ability.

The Covid-19 pandemic will have increased anxiety levels across the population and will, for some autistic learners, be a confusing and negative experience.

It becomes clear why autistic learners might experience anxiety when we take account of what autism is. Autistic individuals have:

- communication and social interaction difficulties

- sensory processing differences

- difficulties with social imagination and flexible thinking.

There are many reasons why autistic learners might experience higher levels of anxiety than their peers.

- Ours is a confusing and unpredictable world.

- Autistic learners’ daily experience may be confusing and unpredictable. Dealing with a series of unpredictable events or disrupted expectations can result in increased stress and anxiety.

- Understanding people and social situations (social awareness).

- Some learners may experience daily events and reactions of people as arbitrary and unexpected, meaning that life is likely to be experienced as random and scary.

- Some learners who may be more socially aware might have the knowledge that they do not understand people the way that other children do, and they may realistically predict that they will make mistakes in interpreting emotions, situations or social rules and expectations. They might also be aware that they do not have effective strategies to manage when they experience the feeling of always ‘getting it wrong’.

- Patterns of thinking – autistic learners can have thinking styles which focus on details rather than the bigger picture (weak central coherence). This thinking style may be linked to heightened experiences of anxiety. It is possible that those with a narrow focus in thinking may focus only on the detail of the ‘threat’ or ‘worry’ and fail to see the elements of the ‘big picture’ that might be reassuring.

Anxiety can manifest itself in a variety of observable behaviours, as well as internal experiences that will vary by developmental stage.

Some learners with more advanced language and social awareness may be able to express how they are feeling with words. Other children and young people with limited language, or even with advanced language, express their anxiety through behaviours. These behaviours should be interpreted as a sign of distress rather than thought of as ‘challenging’.

Common signs of anxiety

Some common signs of anxiety and distress might include noticeable:

- physiological signs (e.g. pale, sweating, trembling, restlessness)

- communication changes (e.g. increased or decreased chatting)

- reports of physical symptoms (e.g. stomach ache, headache, nausea or muscle pain).

Autistic learners experiencing anxiety may have difficulty sleeping and concentrating and may have a sense of losing control or have repetitive thoughts about perceived threat. They may feel worry, irritability or distress.

Those around the learner may not pick up the signs that they are anxious until they see the more obvious signs listed in the stages below. The behaviours have been grouped broadly by the three developmental stages within Figure 12.

Activity 11

Click and reveal on titles and descriptors

Social partner stage – Children and young people who do not yet use meaningful words who may communicate through actions and behaviour may show anxiety in the following ways:

Answer

- crying or screaming

- hitting out or kicking

- self-harming such as hitting head off objects

- withdrawing or refusal to take part

- an increase in repetitive movements, play sequences or phrases

- tantrums

- flight (running away)

- increased rigidity of routines/topic.

Language partner stage – Children and young people using simple language and short sentences to communicate may show anxiety in the following ways:

Answer

- hitting out or kicking

- flight

- withdrawal

- tantrums

- directing/trying to control the behaviour of or interactions with peers to make play predictable

- refusing

- arguing

- attempt to control the order of what is happening

- repetitive questions

- increased rigidity of routines/topic.

Conversation partner stage – Children and young people using complex language in a conversational way may show anxiety in the following ways:

Answer

- school refusal

- avoidance of unpredictable situations or those requiring social interaction

- flight

- hitting out or kicking

- hurting themselves

- seeking reassurance (possibly in an idiosyncratic way)

- concern about how they appear to others

- refusal

- arguing

- regression to previous habits e.g. repetitive questions or phrases that they no longer normally use

- increased rigidity of routines/topic.

The behaviours listed above may look different in a younger or older child (e.g. a 4-year-old hitting out is very different to a 15-year-old hitting out), but the behaviour may serve the same communicative purpose. It is important to note that there is no such thing as an autistic behaviour and these are ways anyone can express anxiety.

Anxiety build-up

As anxiety increases, a learner is less able to connect to their coping strategies or to their problem-solving skills and is therefore likely to become more inflexible than their normal presentation. An anxious autistic learner might well be avoidant and may appear oppositional when invited to try new experiences; refusing these experiences might be perceived as keeping themselves safe and less vulnerable than venturing into the unknown.

Supporting autistic learners with social anxiety

You will need to download this file.

Download an overview of ‘Supporting learners with Social Anxiety’.

Activity 12 Reflective Log

In your Reflective Log, consider the following questions.

- What is your setting doing to support autistic learners who experience anxiety and help reduce it?

- What further improvements could be made?