Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 8 March 2026, 10:28 AM

Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation Module: 19. Community Mobilisation

Study Session 19 Community Mobilisation

Introduction

This study session will help you understand community mobilisation in relation to the Health Extension Programme. You will be the leader of health activities at a community level, and you should be able to mobilise the community for a particular health action. This session emphasises the skills needed and an understanding of concepts required to enable you to mobilise a community and promote community participation.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 19

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

19.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 19.1)

19.2 Describe some of the criteria that bind a community together, and describe how to work with the community. (SAQ 19.1)

19.3 Describe the techniques that are required to involve a community in health activities. (SAQs 19.2 and 19.3)

19.1 Community and its advantages

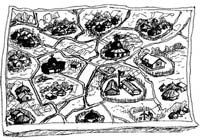

A community is a group of people, based on common values and norms, who live within a geographically defined area and who share a common language, culture or values (Figure 19.1). In short, a community refers to an area or a village with families who are dependent on one another in their day-to-day transactions, thereby creating mutual advantages.

19.1.1 Concepts of community mobilisation

To mobilise is to get something or someone on the move. It follows then that community mobilisation is about organising the community and all the resources available in the community to move them towards achieving a certain health programme goal. Having this concept in mind, community mobilisation is defined as a capacity building process, through which individuals, groups and families (such as model families), as well as organisations, plan, carry out and evaluate activities on a participatory and sustained basis to achieve an agreed goal (Figure 19.2). This might be from their own initiative — or a goal stimulated by others.

Community-based participatory approaches to community mobilisation will help to achieve reliable and sustainable healthy lifestyles and behavioural changes. Through community involvement, lay and professional people study health problems, pool their knowledge and experience, and develop ways and means of solving their health problems. Your role is to help the community organise itself so that learning will take place and action follows. The health activity cannot achieve the intended goals without involving the community. This can only be achieved by building on the community’s knowledge and beliefs through a continuous dialogue, and not by dictating to them what they should do.

A community should be mobilised and technically supported to take action to identify their own health issues or problems if essential health care is to be made available to every household in Ethiopia.

19.2 Mobilising your community

There are important things that you need to bear in mind while mobilising your community. You need to encourage participation by as many community members as possible. This means working actively with the community to solve their own health-related problems. You really need to know your community.

Think about the community that you live or work in. Imagine a co-worker from another area is coming to join you. What do you want to say right at the beginning about your community? If you have not yet started to work as a Health Extension Practitioner think about the community in which you live.

Write the following information about your community below:

Name of your village/kebele__________________________

Languages they speak_______________________________

Festivals they celebrate ______________________________

Beliefs and values they have__________________________

Religion__________________________________________

Resources_________________________________________

Are there any particular health problems in the community?

Your answers will be individual to you and your community. The point of this question is that the more you know about the community (Figure 19.3), the more likely you will be to design health-related projects that fit the individual needs of that community.

However, knowing your community is only the beginning. Community mobilisation is an active process. Community participation is necessary at every step of the process, from identifying problems to solving the problems.

At the stage of identifying problems it is not good to say: ‘I know what your problems are.’ It is essential to encourage the community to identify their own problems first; then they will be more ready to deal with them. Secondly, get them participating in finding solutions. Communities have different amounts of resources, and they also have different values and beliefs. Things that work best for one person or one community may not work for another. So do not assume you know what the best solution is.

Be clear about what you can and should do, and also about what the community can and can’t do. Always allow them to do some things for themselves. Together with the community, you should ask: ‘What problems can we identify?’, ‘What are the best solutions we can select?’, or ‘What action can we take?’ Following any community health activities, you should always get community members to participate in the evaluation. Discuss the results with the community, and in that way you can help them to learn. If they know why progress was achieved, or an action succeeded or failed, they will be able to make better efforts next time.

Now look back at the initial information you have set down about your community. You may have identified a health problem or problems. But is the community aware of these? If you asked them, would they also identify the same problem?

As a health worker, you may have noticed problems that are not seen by the community (for example, you may have data about infant mortality that confirm a higher than usual incidence). But is the community aware of this? Remember, as we have said, always begin by asking your community about problems — not telling them.

19.3 Equipping your community

The greatest improvement in people’s health will be as a result of what they do to and for themselves. It is not the result of external interventions. Millions of daily decisions about health and disease are made by individuals and families at their own homes, not by health workers. So in order to make these millions of decisions become healthy decisions, you should equip your community with appropriate skills and knowledge, and empower them through community participation. The greatest resources you have in your community are good relationships with individuals (Figure 19.4) and groups; therefore, you should mobilise them to pool the resources available in the community, including labour power.

19.4 The advantages of community mobilisation

There are several advantages of community mobilisation that will help local ownership and the sustainability of the health programmes. Community mobilisation helps to motivate the people in your community and encourages participation and involvement of everyone, as well as building community capacity to identify and address community needs (Figure 19.5). Community mobilisation also promotes sustainability and long-term commitment to a community change movement. In addition, it motivates communities to advocate for policy changes to respond better to their health needs.

Look back at the previous paragraph and make a list of what you think are the benefits of community mobilisation.

If the community owns its health activity, then this is more likely to be sustainable. By being involved they will also be empowered, partly by advocating for health policy changes.

Community mobilisation has several key steps (Box 19.1) and can come from the community itself, or may be initiated by outsiders. For instance, the community may request the local health workers to provide a health education session on malaria. This is an example that has been initiated by the community members. On the other hand, you may consider that female genital mutilation is a serious local problem and decide to mobilise the community to fight it. This is an example of community mobilisation initiated by others.

Box 19.1 Key steps in community mobilisation

- Create awareness of the health issue

- Motivate the community through community preparation, organisational development, capacity developments and bringing allies together

- Share information and communication

- Support them, provide incentives and generate resources.

There are many tools and techniques for collecting information that will help you to know more about your community. Here are some examples:

- Direct observation

- Group interviews

- Sketching maps

- Role-plays

- Stories

- Proverbs

- Workshops.

For example, to find out about the history of the community, you can create a ‘historic profile’. This allows you to become familiar with the history of the village chosen for community mobilisation. A village history will include the significance of its name, the people who founded it, and the major events that have marked it through time.

19.5 Techniques to involve a community

For you to work best with the community, you need to identify the right people in the community who can explain to you their habits, customs, values, taboos and the rules of that community. These are sometimes called the community norms. You must also identify the people who can introduce you to the most influential members of the community, such as the kebele leaders, and ask them to introduce you to other co-workers, and to the community as a whole. It is also good to know and develop relationships with other influential people within your localities, such as the religious leaders, in order to be accepted by the community. These influential people are often called opinion leaders and are important people to keep informed about the sorts of health issues you feel should be addressed. Indeed, as you move forward, everyone in the community needs to be informed about these matters.

To be involved in the community, you need to develop the required or acceptable behaviour. So you need to be polite, persuasive and be good at being a role model. This will involve you being patient, a good listener, tolerant and self-restrained, honest, open, non-judgmental and respectful.

What three things do you think you need to work on at the beginning of your community mobilisation activities?

You should:

- Get the support of influential people in the community, including those who are called opinion leaders.

- Be sure that all the people of the community are informed about the health problems you want to address.

- Behave in an open and honest way, and try to act as a role model in the community.

19.5.1 Community relations

Community relations are those methods and activities that you undertake to establish and promote a setting that is conducive to good relationships, and which create a strong bond with the community. Your methods of communication with communities typically involve a series of local meetings, but can also include special events and wider community meetings (Figure 19.6). The community members are central to all parts of the Health Extension Programme. If you are not involving the community the Health Extension Programme will fail (Box 19.2).

Box 19.2 Working with the community

- Go to the community

- Love with them

- Live with them

- Learn from them

- Link your knowledge with them

- Start with what they have

- When you finish your job, the people will say we did it all by ourselves. (Adapted from the words of the Ancient Chinese philosopher and teacher, Lao Tsu.)

19.5.2 Effective networking

To work effectively with the community, you need to understand who holds the power in the community and how they influence community decisions. The community has an important role to help identify health problems and use the available resources in the village to plan activities and then act to improve the community’s health. For the successful implementation of development activities, you need to involve everyone in a community network, especially those with power (the decision makers in the community), as early and as often as possible.

You can engage the community using one or more of the participatory methods, such as small groups (Figure 19.7), large meetings, community conversation, local celebrations or exhibitions. You should also identify health objectives for your community, and use the right approaches to engage the whole community. Invite the whole community and representatives to meetings, and secure their approval for your advocacy objectives. Then ensure clarification of the roles of all the people involved.

If you had to express one overwhelming message about how to go about community mobilisation, which of the ones below would you choose?

- Invite only key opinion leaders to ensure that messages do not get confused.

- Prepare a health objective thoroughly yourself and then present it to community leaders.

- Invite the whole community to get involved as much as they can.

- Prepare a health objective which is ‘right’ for the community, and drive it through regardless of what they say.

We think the key message is to involve the community as much as you can (Number 3). If you conceive and carry out a plan only talking to opinion leaders, or only based on your own views, you will not have the community with you.

Community mobilisation at its best does not merely raise community awareness about an issue, or persuade people to participate in activities that have been prioritised and planned by others. Rather, it is a comprehensive strategy that includes exploring the health issues in the community, developing a plan of work, working with the community to establish credibility and trust, working together with the community to implement your plan, and raising community awareness about important health issues. It also involves working with community leaders, model families and others to make sure that those most affected by the health issues are involved in the necessary action.

19.6 The action cycle of community mobilisation

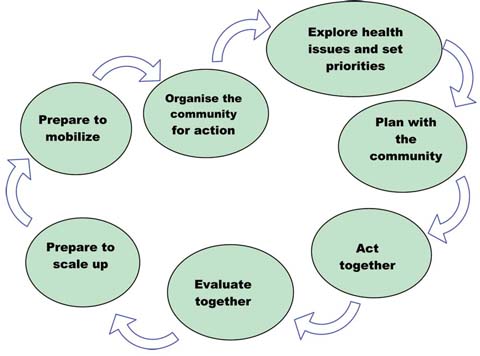

You should start the mobilisation process by organising your plan of work with the community. After that you can explore all the most important health issues in order to understand what is currently happening in the community. In addition, you can identify why any specific problems are occurring. You should look for helpful or harmful health practices, beliefs, attitudes and knowledge within that community that are related to the health problem under consideration. Once the health issues are fully explored, you can set priorities, develop a more detailed plan of work, and carry out the plan. During implementation of the programme, you should monitor and finally evaluate your activities. If the programme seems successful, you should think about how you could scale up that method to a larger number of households. In this way, the action continues. These activities are known as the community action cycle (Figure 19.8). An example of how it works is described below the diagram.

19.6.1 An example of community mobilisation:

Step 1 Identify a significant health problem, for example female circumcision.

Step 2 Plan and select a strategy to solve the problem (for example, conduct a workshop for influential people in the community for sensitisation on the issue).

Step 3 Identify key actors and stakeholders (village chief, Imam, heads of families, etc.)

Step 4 Mobilise these key actors and stakeholders for action (discussions and agreement on what to do).

Step 5 Implement activities to work towards a solution (capitalise on the sensitisation of the people created by the workshop and intensify this through various follow-up activities).

Step 6 Assess the results of the activities carried out to solve the problem.

Step 7 Improve activities, based on the findings of the assessment.

The Health Extension Practitioner, Halima Gebre works in Gorbessa kebele. The village is located in a very remote area where there is no access to any kind of transportation. Most pregnant women from the village have no access to transport even if difficult situations arise during their delivery. There is no track or road for cars to travel between the village and the nearby district where the hospital is situated. This year four pregnant women with obstructed labour have died. Most of the community members would not be able to carry a stretcher as far as the hospital.

If you were a Level IV Health Extension Practitioner in this community, what action would you take to help these kinds of mothers? How would you mobilise the community to solve these problems? Obviously this is a big problem and would take a lot of detailed working out. However look again at the steps in the cycle (Figure 19.8), to see if you can begin to map out some of the principles you might use.

Halima has already identified a significant health problem (Step 1). Remember that to mobilise the community for a health action, such as getting better transport facilities in case of medical emergencies, Halima will have to do other things as well:

- She needs to work out a solution and get the support of influential people in the community (opinion leaders) (Steps 2 and 3).

- After these initial stages, she needs to use these key people. Perhaps the kebele administrator could be asked to talk to local government officials.

Of course we don’t know the later stages of Halima’s work, but you can see the way the initial stages are performed.

Halima will also need to be sure that all the people of the community are informed about the problem, and then get the maximum number of people involved. This will not only mean that people ‘own’ this problem, but hopefully the community will also strengthen its capacity to do things for any health issues that arise in the future. Box 19.3 summarises the key messages about community participation.

Box 19.3 Active community participation

- Know your community well, and understand their problems and their needs.

- Be aware of existing health beliefs and practices that exist in the community.

- Always listen to community members carefully.

- Do not rapidly introduce new interventions that are different from existing practices and beliefs. Take gradual steps to introduce such practices.

- Try to analyse community dynamics and adjust to each situation.

- Involve the entire community in the programme right from the beginning.

- Give respect and importance to negative experiences of the community, if any, and try to minimise the negative feelings verbally and in your actions.

19.7 The advantages of community participation

Local people have a great amount of experience and insight into what works for them, what does not work for them, and why. So they contribute to the success of any health intervention. Involving local people in planning can increase their commitment to the programme and it can help them to develop appropriate skills and knowledge to identify and solve their problems on their own. Involving local people helps to increase the resources available for the programme, promotes self-help and self-reliance, and improves trust and partnership between the community and health workers. It is also a way to bring about ‘social learning’ for both health workers and local people. Therefore, if you involve the local community in a programme which is developed for them, you will find they will gain from these benefits.

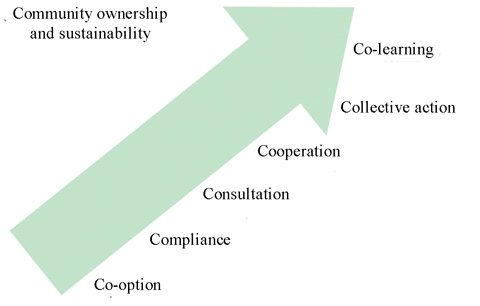

19.7.1 Levels of community participation

All participation is not equal. The extent of participation in programmes can vary from minimal to complete ownership. Figure 19.9 shows increasing degrees of participation from the low end of co-option to the upper end of collective action. This shows that as community participation increases, community ownership and capacity increases. Box 19.4 defines different degrees of community participation.

Box 19.4 Degrees of community participation

- Co-option: Local representatives are chosen, but have no real input or power.

- Compliance: Tasks are assigned with incentives, but outsiders decide the agenda and direct the process.

- Consultation: Local opinions are asked for, and outsiders analyse and decide on a course of action.

- Cooperation: Local people work together with outsiders to determine realities; responsibility remains with outsiders for directing the process.

- Collective action: Local people set their own agenda and mobilise to carry it out, in the absence of outside initiators and facilitators (Figure 19.10).

- Co-learning: Local people and outsiders share their knowledge to create a new understanding, and work together to form action plans, with outsiders facilitating.

There are different tools to help the community to participate effectively. Two of the commonly used participatory tools are community mapping and community conversation.

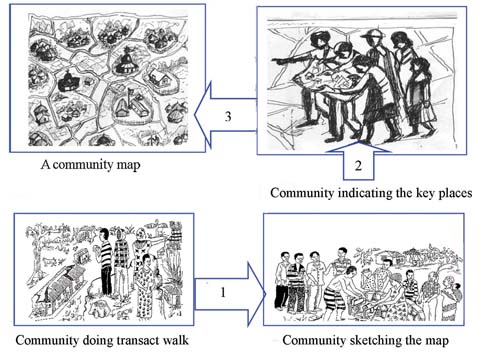

19.7.2 Community mapping

During community mapping a map is drawn of selected physical features on a flat surface (Figure 19.11). The selected features for a village could be:

- The natural resources.

- The poverty pattern(s).

- The territory of the village.

- The housing pattern(s).

- The cropping pattern(s).

- The space and the area the village occupies.

Community maps can help you to identify households, community water points, health services, etc. The mapping exercise is done with the participation of the community members, and helps the community to explore and visualise the community and their local environment.

Prior to the mapping, do the following:

- Choose a place where most of the community members can participate.

- Involve the community to collect materials like ash or sand to sketch the map.

- Go round the localities on foot, or do a walk to see the key areas like the site of the health centre, the kebele office, the church, the main road, the river, etc. Ask the community members to sketch the map, and put signs for those key areas using ash or sand.

Clearly, community mapping is a collective exercise. But if you have not done it before, begin by just trying out a map for yourself on a piece of paper. Do a walkabout and draw in a rough plan of the village — where the crops are, where the various public places are (Figure 19.12). After you have done this, you may want to try thinking about where there are particular pockets of poverty in the village, or locations where you know there are more health problems than others.

Doing an exercise like this does not compromise you doing it with members of the community. If you aren’t used to mapping then a rehearsal is probably a good idea. When you do it for real a number of you will go on a walkabout, and in these circumstances you will find that many eyes find different things from one pair of eyes. You will get a genuinely communal map. You will also have a much richer map (Figure 19.13).

Summary of Study Session 19

In Study Session 19, you have learned that:

- Community mobilisation is a capacity building process through which you will be able to work with the community to identify and plan health activities.

- Always think of undertaking community mobilisation when the problem affects the whole community and when local resources, as well as larger-scale changes, are required to address the problem.

- The greatest benefits of community mobilisation are to build community capacity and to help the community identify and address its own needs.

- In community mobilisation, the first step is to investigate the health problems, then develop an action plan.

- Community participation as part of community mobilisation is critical for success.

- Participation enables local people to develop commitment, skills and knowledge, and it enhances the partnership with health workers.

- You will need to identify the right people in the community who can explain to you the norms, taboos and rules of the community before you start work in the community.

- Community mapping is a good community participatory tool.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 19

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering theses questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 19.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 19.1 and 19.2)

What do you understand by the word community? Describe some of the features that bind your community together.

Answer

A community is a group of people who share some common interests and live within a geographically defined area; community members tend to have a common language, culture, or values and norms.

SAQ 19.2 (tests Learning Outcome 19.3)

Why is community mobilisation important when tackling health issues?

Answer

Community mobilisation is important when tackling health issues because it has advantages such as:

- local ownership and the sustainability of the programmes

- motivating the people and encouraging participation

- building community capacity to identify and address community needs, and empowering the community

- helping to mobilise local resources.

SAQ 19.3 (tests Learning Outcome 19.3)

List the steps in the community mobilisation action cycle.

Answer

Here are the steps of the community mobilisation action cycle:

Step 1 Identify a significant health problem.

Step 2 Plan and select a strategy to solve the problem (conduct influential people’s workshop for sensitisation on the issue).

Step 3 Identify key actors and stakeholders (village chief, Imam, heads of families, etc.)

Step 4 Mobilise these key actors and stakeholders for action (discussions and agreement on what to do and how).

Step 5 Implement activities to work towards a solution (capitalise on the sensitisation of the people in the workshop, and intensify this through various follow-up activities).

Step 6 Assess the results of the activities carried out to solve the problem.

Step 7 Improve activities, based on the findings of the assessment.