Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 21 February 2026, 9:51 AM

Session 2 Online learning

Introduction

This second session of the course introduces some key terms in online education. These include the distinction between synchronous and asynchronous learning. In a face-to-face environment, almost all teaching is synchronous – the teacher is present at the same time as the students. This approach can work online, but there are times when there is no need for everyone to engage at the same time, so an asynchronous approach is better.

The session also covers blended learning, which combines the advantages of both online and face-to-face teaching. One way of doing this is by using a ‘flipped classroom’ approach.

There is also an opportunity to develop the plans for online education that you began to think about in your reflection at the end of Session 1.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this session, you should be able to:

- use digital communications to support learning;

- consider the communication and access needs of different learners;

- participate actively in social media relevant to your professional role and interests;

- facilitate learning in digital settings.

1 Synchronous and asynchronous

One of the most common ways to think about online education is to consider whether it might be synchronous, asynchronous or a mixture of both.

Synchronous learning

Synchronous learning takes place when the educator is present at the same time as the learner(s). This is almost always the case in a face-to-face environment. Synchronous learning can also take place in an online setting, using video conferencing and live chat or instant messaging. As in a face-to-face environment, learners in synchronous online sessions can ask questions and receive immediate responses.

Delivering courses synchronously, whether face to face or online, limits flexibility for learners. Because everyone has to be present at the same time, all learners must work through the course at a similar pace, with few opportunities to vary the pace to fit individual needs. If learners are not able to engage when the lesson is running, for example because they are ill or have other commitments, they miss it (although some institutions will record lessons for learners to view later).

Educators’ roles in online synchronous education are similar to their roles in face-to-face settings. Synchronous learning may feature webinars (live online lessons), group chats, or drop-in sessions where educators are available to help at a particular time. However, teaching synchronously online also requires some new skills, including ways of managing the faster pace of this form of teaching.

Asynchronous online learning

Asynchronous online learning does not require learners and educators to engage at the same time. Learning materials are posted online, and learners work through them in their own time and at their own pace, communicating with each other and the educator via discussion boards or forums, or perhaps by email or social media such as WhatsApp. Good asynchronous teaching makes use of a variety of media, including (but not limited to) audio and video clips.

When courses are asynchronous, learners can work at their own pace and at times of day that are convenient for them. The pattern of their input will be very different to that in synchronous lessons. Learners are likely to make many short visits to the discussion boards or forums. Although timing is flexible, there may still be deadlines for work to be submitted for feedback, and there is likely to be a recommended schedule for learners to follow so that they have some idea of what they should be doing and when.

As you will discover later in this session, a ‘blended’ approach can be used to bring together the advantages of synchronous and asynchronous learning, and of online and face-to-face learning into a single experience.

1.1 Collaboration

Collaboration between learners, and between learners and educators, is an important factor in both synchronous and asynchronous online education. It helps to create a sense of connection between all participants and to build a sense of community and shared purpose.

Collaboration in a synchronous environment can be achieved in much the same way as in a classroom, with discussions and group tasks. In an asynchronous environment collaboration can be trickier, but is still very important in reducing the sense of isolation some learners feel when working online. Discussions and group tasks can work just as well asynchronously as synchronously. In fact, asynchronous discussion and collaboration can sometimes work better: because of the lack of time constraints, learners can spend time composing a higher-quality response or contribution.

1.2 Reflections

Every session of this course presents video clips made at home by educators who have moved their teaching online. These provide authentic examples related to each session’s material. At the same time these clips highlight how simple videos can be produced and used for online education purposes.

The following video was made by an educator called Sarah, who works in the UK. Her experiences reflect some of the concepts that are introduced in this session and will be discussed again later in the course.

Activity 2.1 Different approaches

As you watch the video, or read the transcript, consider which of the approaches Sarah mentions are synchronous and which are asynchronous.

- Make a list of the main tools available at your university that can be used to teach synchronously.

- Make a list of the main tools available at your university that can be used to teach asynchronously.

You may find it helpful to ask your colleagues about tools they use, to see if you can extend these lists.

Transcript

Comment

This activity prompts you to consider the variety of teaching tools that are available at your university. Some of these will be supplied by the university, but others are freely available online. Some of these tools will be introduced during the course, so you may want to return to these lists whenever you find out about a tool that you would like to add to your repertoire.

1.3 Asynchronous and synchronous teaching opportunities

Throughout this course, you will be introduced to relevant research papers. If you want to explore the ideas presented in them in more detail, full references are included at the end of each session. The first such paper, by Murphy et al. (2011), reports on interviews with 42 Canadian high school distance education teachers regarding their views on synchronous and asynchronous online teaching activities. The authors reported the following findings:

- Teachers combined synchronous and asynchronous online teaching in different ways. Some taught entirely asynchronously. Others combined asynchronous teaching with synchronous forms, such as scheduled classes or times where they would be available for tutoring and responding to students.

- All those interviewed made some use of asynchronous online teaching, such as providing learning materials for students to work through in their own time, using online quizzes, or supporting students to ask a question via email or forum and receive a response at a later time.

- Teachers suggested that many students preferred asynchronous and text communication. One observed that it was rare for students to request voice chat rather than text communications. Another noted that students could email to ask multiple questions and the teacher could then take some time to construct a response.

- Some teachers felt that the best way of addressing a particular student query was through synchronous communication such as video conferencing or use of a shared online whiteboard.

- Teachers felt that synchronous sessions, including time for socialising and informal discussion, could help reduce feelings of isolation.

Activity 2.2 Synchronous and asynchronous online education

Consider how synchronous and asynchronous modes of online education could be applied in your work.

Make a note of short examples – either real or imagined – that fit the following criteria:

- A situation where synchronous approaches would be appropriate and beneficial in supporting learning.

- A situation where asynchronous approaches would be appropriate and beneficial in supporting learning.

- A situation that combines synchronous and asynchronous approaches to support learning.

Comment

This activity is designed to help you think about online education in your own context. One of the very first considerations in taking education online is to decide which elements lend themselves to synchronous learning, asynchronous learning, or both.

The study by Murphy et al. (2011) was conducted in the context of high school distance education. Some of the findings may hold true for you, but they may not be universally applicable.

Consider the practical issues, the preferences, and the benefits in your own case. There could be very good practical reasons for using an asynchronous approach – for example, students might not all be available at the same time. Or a synchronous approach might benefit students by providing immediate responses to queries. Some students may like the way a synchronous discussion can create a sense of community and engagement; others may prefer the slower pace of an asynchronous activity where they can craft a question or response and reflect on it before sharing with others.

It is often sensible to make use of both forms of teaching to provide a range of experiences and opportunities for learning.

1.4 Interacting with learners

One of the most noticeable differences between synchronous and asynchronous learning is the nature of the interactions between learners and educators. These include providing feedback, answering questions, or guiding learners through a particular activity.

In a synchronous learning environment, educators can deliver feedback immediately, whenever it is required. However, while the face-to-face environment allows for visual cues when delivering feedback, these are not always possible – or may take different forms – in the online environment. With online education, it is important to build in opportunities for feedback, both from educator to learner and from learner to educator, to make up for the loss of the face-to-face cues.

In an asynchronous setting, feedback will be given some time after a learner has asked a question, unless it is provided automatically. Sometimes several iterations of a conversation are needed to help learners with an issue, which takes time. This is a reason why peer feedback is often used in these settings, as it gives learners opportunities to reinforce their learning by helping each other without having to wait for input from an educator (Gikandi & Morrow, 2016).

1.5 Motivation and support

Keeping learners motivated and attentive online can be more challenging than in a face-to-face environment where an educator’s personal enthusiasm can have an immediate influence on learners. Online environments will include some learners who are very self-motivated, some learners who are comfortable with online learning, and some learners who are less certain of how to interact. There can be particular challenges for the learners who are least capable of structuring their studies independently.

Starting each course with a highly structured set of tasks enables educators to see quickly which learners are not completing the tasks on schedule or in the expected way. These learners can then be followed up individually and offered advice on how they should approach the tasks and their online learning experience.

Maintaining order in an online class can be more straightforward than doing so face to face. In a classroom, individual learners can disrupt the lesson or distract other learners, but the online environment is different. During synchronous events, educators can combine their existing classroom skills with the features of the environment (such as controlling whose microphone is enabled at any given time) to avoid any one learner dominating discussions. In asynchronous discussions, inappropriate or tangential comments can be moderated or, if appropriate, challenged publicly.

Some interactions will take place in channels to which educators do not have access, such as WhatsApp groups or private text chats. Disputes, relationship breakdowns and bullying can happen out of sight of the educator, just as they can outside the physical classroom. If learners are unusually reticent in an online session, or suddenly stop engaging with a discussion thread, it can be worth contacting them individually to find out what has prompted the change in their interaction/behaviour.

1.6 Developing skills and confidence

Supporting learners online requires a different skillset to supporting learners in a face-to-face learning environment. A study by Price et al. (2007) into the differences between learner perceptions of teaching in these environments found that online educators should have a greater pastoral focus than face-to-face educators and that both educators and learners needed guidance and training in communicating online.

Without a physical classroom environment, learners can feel isolated and unsupported. An increased pastoral presence by educators, initiated via online communications, can help reduce those feelings and develop a more comfortable experience. A large-scale follow-up study by one of Price’s co-authors (Richardson, 2009), which looked at the experiences of learners receiving tutorial support on humanities courses, concluded that, with adequate preparation, the online environment need not be a lesser experience for learners in terms of support:

‘Provided that tutors and students receive appropriate training and support, course designers in the humanities can be confident about introducing online forms of tutorial support in campus-based or distance education.’ (p. 69)

An online learning experience may lead to technical problems. While it is not usually necessary to become a technical expert, it is useful to find out how to deal with the common technical issues that learners are likely to face. For example, if learners are given advice about common techniques to resolve audio issues during synchronous online sessions, it can save time, reduce stress and build learner confidence.

Your students’ confidence to approach new technologies and deal with any associated issues will grow as they gain experience, and this will make learning online much more enjoyable for them. When introducing a new tool or technology, set aside time for students to become familiar with it. Introducing playful activities at the start will allow them to experiment in a low-risk way. There may also be training or development opportunities focused on specific learning technologies that can raise the confidence of both educators and students.

Activity 2.3 Motivating and engaging students online

Watch the video ‘Engaging and motivating students’, which summarises views from a range of experts on student engagement.

Transcript

As you watch, make notes on useful tips that you would like to incorporate into your practice.

If you have tips from your own practice, you could share these on the course community of practice Facebook group. Check the group to see if anyone has made suggestions that you could add to your notes.

Comment

This activity should help you to begin thinking, in broad terms, about what you might like to try in terms of motivating and engaging students online. You can also share your ideas and read others’ suggestions via the course community of practice Facebook page.

2 Blended learning

Sometimes learning and teaching do not take place entirely online or entirely face to face. ‘Blended learning’ refers to a course that includes both online and face-to-face elements.

A blended approach can bring together three core elements:

- classroom-based activities with the teacher present;

- online learning materials;

- independent study using materials provided by the teacher.

This blend of activities means that educators also have a blended role, adding a ‘facilitator’ element to their work as they organise and direct group activities, both online and offline.

Blended learning can make use of the main advantages of synchronous learning:

- teacher presence;

- immediate feedback;

- peer interaction.

It can combine these with the main advantages of asynchronous learning:

- independence;

- flexibility;

- self-pacing.

It can also help to avoid the possible issues of asynchronous learning, such as learner isolation and difficulty with motivation, as well as the possible issues of face-to-face learning, such as lack of flexibility and the need to work at the same pace as others.

2.1 Flipped classrooms

‘Flipped learning’ reverses the traditional classroom approach to teaching and learning. At home, learners watch videos, listen to audio recordings, read books or worksheets. These resources allow learners to work at their own pace, pausing to make notes where necessary. Some learners – though not all – will be able to access help and support from their peers or family members. This independent study means there is time in live sessions with the educator for activities that encourage learners to think critically about the information they have studied. Live sessions become a time to explore subjects with the support of the educator and fellow learners.

The flipped learning approach has two parts: direct instruction at home and an interactive element in the seminar room or lecture theatre. The direct instruction can focus on readings or audio recordings, but often consists of videos. These may be ones made by the educator, or they could be ones that have been shared online.

Activity 2.4 The flipped classroom

This video synthesises the benefit of a flipped classroom approach.

Watch the video, or read the transcript, and make a note of three benefits of the flipped classroom.

Transcript

Comment

This activity is intended to introduce you to the concept of the flipped classroom approach, and to help you to identify the benefits it may have for you in your own context.

The benefits suggested for the flipped classroom approach include the ability for students to work through materials at a pace that suits them, and a reduction in boredom for students who are finding the material easier. The educator can spend class time addressing individual needs.

There is a wider theme that can be found in this video and elsewhere in this course. This is the way that the role of an educator can change in response to a change in approach using technology. In the case of the flipped classroom, the educator is seen to become more of a ‘coach, mentor, and guide’, rather than acting primarily to deliver knowledge. You might see this as a benefit, depending on your point of view on what the role of an educator should be.

Now that you have been introduced to some of the unique aspects of online education, the differences between synchronous and asynchronous elements, the possibilities of blended learning and the notion of the flipped classroom, the next activity prompts you to reflect on your own practice and how it might fit with what you have learned so far.

Activity 2.5 Making plans

Now that you have read a little about the basics of online education, think about your goals in this area. These may be wide-ranging or they may focus on one task that you do regularly. Note answers to the following questions if you can:

- What do you want to achieve online? Do you aim to transfer online a small or substantial element of face-to-face teaching? Do you want to improve the online teaching that was developed quickly during the pandemic? Do you want classes to take place entirely online or would a blended approach be better? What is the best balance of synchronous or asynchronous activities likely to be? Is a flipped classroom approach appropriate?

- Who are your students? What are their online skills? What support might they need to study successfully online?

- What resources do you have that you might be able to repurpose to support online learning?

Record your responses below and, if you wish, share some ideas in the course community of practice Facebook group.

Comment

This is one of a series of activities that appear throughout this course, helping you to develop a plan for taking education online or for developing your current practices. You may find it helpful at this stage to keep a range of options available, perhaps listing several ideas for each point.

3 Learner anonymity, backchannels and social interactions

In some online learning environments, all interactions through university channels will be obviously attributable to individual students. Forum posts will usually only be possible from students’ institutional accounts, and therefore their name will be attached to everything they contribute. Similarly, login information for synchronous online events will usually be provided by the university and will identify each student clearly. However, there may be circumstances where this kind of information is not provided by default, and students can choose to create accounts that do not identify who they are.

Anonymity can have a great advantage for learners who are reluctant to contribute under their own name, for fear of giving an incorrect answer, for example, and can be very enabling for an entire cohort if discussing very sensitive topics. However, it can also embolden troublemakers or more dominant personalities, and because of this it can be challenging for the educator to moderate activities where interactions are anonymous.

Any online learning activity carries the possibility of interactions developing between learners in spaces away from the official locations for the online learning, for example, in a student-initiated WhatsApp group. These are known as backchannels, and while there can be concerns about the lack of control over these communications, more often they can be useful to learners (Fiester & Green, 2016). For example, if learners are in touch with each other via an instant messaging app during a synchronous online learning event, they can often help each other to understand the issues covered without having to declare more publicly that they need assistance. This can lead to a greater collective advance in learning than would happen if only the official channels were used.

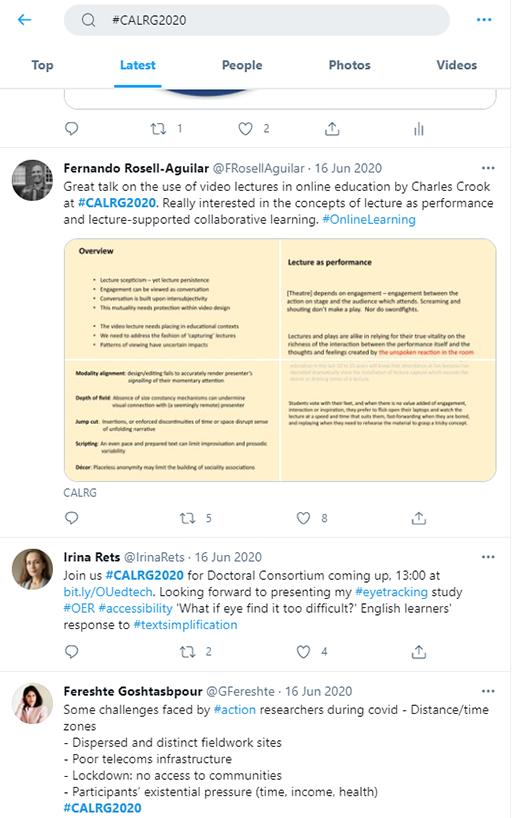

It is important to consider how to encourage and structure effective use of backchannels. One example of backchannels being used to great effect is the use of Twitter and a dedicated hashtag to synthesise and discuss presentations during conferences. For example, the following image shows some of the uses of the hashtag #CALRG2020 during the CALRG (Computers and Learning Research Group) 2020 annual conference:

4 This session’s quiz

Check what you have learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab, then return to this session when you’re done.

Summary

This session has introduced some of the core concepts in online education. Whether activities are synchronous or asynchronous is a key distinction in facilitating learning online, and deciding which activities or resources should be used synchronously and which asynchronously is an important skill. Blended learning and flipped classroom techniques could become a fundamental part of lesson planning for online education providers as they include both face-to-face and online elements.

The next session will look at what makes effective online learning and how education theories can inform online education. Before moving on, however, take some time to reflect on this session in the following activity.

Activity 2.6 Reflecting on progress

Watch the video, or read the transcript. In it, Rita reflects on Session 2 from her perspective as an educator. Take some time to make notes on the following questions:

- How does what you have learned in this session relate to your own role?

- What changes, if any, could you make to your practice or to the wider practice at your university as a result of what you have learned?

Transcript

You can now go to Session 3.