Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 21 February 2026, 9:51 AM

Session 3 Understanding online learning

Introduction

How do universities get started with online education? In this session, you will look at some of the principles that underpin effective online teaching, and how learning theories can inform approaches to online provision. Following this, you will be introduced to a categorisation of the technologies used in online teaching and learning. Pulling all of this together should enable you to plan for learning and teaching facilitated by technology.

Practitioner reflections

This session begins with a clip from Leanne, who talks about some of the tools and concepts she has found useful in her teaching. In it, she refers to ‘learning objects’, by which she means the different elements of her online teaching. As you watch the video, or read the transcript, make a note of the different types of work Leanne has to do in order to take her teaching online, and consider in each case how other professionals could help her to complete these tasks.

Transcript

Learning outcomes

By the end of this session, you should be able to:

- find, evaluate, manage, curate, organise and share digital content for learning, teaching and assessment;

- share learning and teaching materials and resources on appropriate digital sites and networks;

- understand some of the key principles of online teaching;

- relate theories of learning to strategies that can be used to enhance learning online.

1 Principles of effective online teaching

Session 2 introduced some of the ways in which online and blended learning can create new opportunities and benefits for educators and learners. In order to realise those benefits, certain principles need to be followed to optimise the experience for learners.

Activity 3.1 Challenging preconceptions about online teaching

In response to Professor Ferguson, make a note of any concerns you had not already considered for the teaching context at your university.

Professor Ferguson

I work with a lot of people who are taking their teaching online for the first time and they share certain worries. First of all, they usually enjoy classroom teaching and they don’t want to lose that relationship with and responsiveness to their students. They are worried that students might have an impoverished learning experience when they move online. They also worry that their own role will be reduced – that they’ll become a forum moderator rather than a teacher. Also – if they had to move their teaching online quickly and without support during the pandemic, they may have had a bad experience that reduced their confidence.

However, when they are well prepared and then make the move to online or blended teaching, they have the opportunity to explore the things that can be done online that are difficult or impossible in the classroom. It is possible for students to work through resources at their own pace, rather than at the pace of everyone in the class. They can have deep, reflective conversations, referring back to contributions that were made earlier. They can take time to think about their responses rather than being pressured to come up with an instant answer. And students who had previously struggled to fit regular study in around their family commitments are able to join in fully because there are more opportunities to develop personalised schedules.

Comment

Often educators have preconceptions about teaching online and what they or their learners may ‘lose’ if they take their teaching online. This session’s material and activities are designed to help you to separate perceived advantages and disadvantages of teaching online from the real ones, as applied to you in your own context.

Rather than being a simple binary choice, there are many options and ways of tailoring online learning to any context. It is important to be aware of key concepts and types of tools, consider what is known about these, and to have an approach that allows you to trial ways of facilitating online learning and to understand the results. The course will help you to develop in each of these areas.

Searching the web for ‘principles of effective online teaching’ brings up many different takes on the topic, each slightly different. The text includes a summary of some of the key principles that almost always feature in these lists. They have been gathered from a range of sources, but have been inspired in particular by Cooper (2016) and Hill (2015).

1.1 Create a schedule

In a face-to-face teaching environment, educators are not available to learners at all times of the day and night, every day of the week. When moving to an asynchronous online learning environment it is tempting for learners to expect that educators should always be available. Therefore, educators should be supported to establish a set schedule of when they are, and are not, available to learners.

If students need synchronous support, you can schedule drop-in tutorials. Otherwise, educators, managers and collaborators/support staff need to establish expectations across the department (or across the university) that messages and emails will be responded to within a specific time period. For example, if students contact an educator after a certain hour, they should be aware they will not receive a response until the following morning.

Similarly, educators should provide students with a schedule of expectations – giving them dates for each milestone in the course and following up when students miss core deadlines. Developing this schedule and issuing reminders is work that can be done together with collaborators/support staff, including those who are advising on learning design. Establishing expectations in this way will help to keep on track students who are less able to motivate themselves so they can progress through the course.

Information about core deadlines should be repeated often. Educators can do this, but the information can also be built into the learning environment. If there are to be synchronous learning events where participants are required to engage at the same time (such as webinars and group tutorials), students should be reminded of the event several times in the weeks and days leading up to each event. If there is to be a change to planned activities, for example if an educator will be away and unable to respond to messages for a few days, students should be informed well in advance, and an alternative person should be identified for them to contact if they need assistance urgently.

Educators will need to check at regular intervals how students are doing, evaluate their progression through the course materials, and ensure they are being supported. Collaborators/support staff can help with these checks, using data generated by the learning management system (LMS) or virtual learning environment (VLE) (see Section 3.1 later in this session). Students who respond negatively, and those who do not respond at all, will need an educator’s attention to help them develop study strategies to get them back on track.

1.2 Know the students

One of the first principles when developing any teaching or training course, whether for online or face-to-face delivery, is to understand the audience. Understanding who the learners are is always key to delivering a good online learning experience.

Through your experience, you probably know quite a lot about the students who enrol for your courses. For example, for each student, you may know:

- their age, gender, ethnicity, and any disabilities;

- their professional or working backgrounds;

- the life experiences they are likely to have had;

- their motivation for attending the course.

It is important to keep collecting this kind of information so that educators and collaborators/support staff can continue to use it to improve courses and managers can plan for the future.

When moving to online education, teachers, course designers and collaborators/support staff require a range of different information about students. For instance, it is helpful to know:

- how confident and familiar they are working online;

- which technologies and online tools they are already familiar with (for example, video conferences, webinars, social media);

- how easy it is for them to get internet access and whether access is difficult at certain times;

- which devices they use to get online (for example, phone, tablet or computer);

- whether they need any extra resources to make online material accessible to them, (for example, screen readers or writing tools).

In the following video, Charlotte talks about what happened when she moved her training online as a result of COVID-19. She thought carefully about students’ access to technologies and tools. However, when the time came to run the sessions, she realised that some participants were using older models of phones than she had expected, and also that the structure of sessions needed to be planned very differently to work online.

Activity 3.2 Learning from experience

Watch the video below, or read the transcript, and make a list of changes that could be made by staff at Charlotte’s institution to improve the online training experience for their learners. Note whether the changes would be initiated and made by (a) managers (b) educators and/or (c) collaborators/support staff.

Transcript

Comment

You may have come up with a number of possible changes. Here are some examples:

- Consider learners’ access to technology before planning the training. Depending on the structure of an organisation, this change could be initiated by an educator/trainer or collaborator/support staff (administrator, support tutor etc.).

- Choose an appropriate tool or application for running the training. This change can be initiated by the trainer/educator; however it will require IT and technical staff support to choose the most appropriate and secure tool/app and managers’ support to pay for the licence or other fees (if needed).

- Consider activity types and delivery arrangements. These can be initiated by the educator or trainer when planning a session.

Reflecting on this new knowledge about the students meant the course could be redesigned so that it worked much better.

One way of thinking about different types of learner and how to design an online course to meet their diverse needs is by creating profiles that identify a range of key characteristics. This kind of activity is often referred to as ‘generating personas’, meaning creating descriptions of the sorts of learners you expect to be teaching or supporting. To do this, you can use persona forms such as this one, used by The Open University.

Ensuring an online course is accessible to students with disabilities and those with additional needs is particularly important. In fact, online education has the potential to be much more accessible than face-to-face learning. This is partly because participants do not need to travel, and partly because – with asynchronous training – they can study at their own pace and at a time that suits them.

You will find out more about making online education accessible for students with disabilities in Session 7.

1.3 Foster a sense of community

Learning online is not an individual process – there are many ways of bringing learners together in order to support their studies. Wenger’s (1998) concept of ‘communities of practice’ has become popular in education over the past two decades. Wenger suggests that people who share a common goal or purpose can form a community of practice through which they share insights and experiences. Members of one of these communities are practitioners in a particular area. For example, they might be learning technologists who discuss their ideas and experiences in a shared online space. Participating in a community of practice is a social activity that provides opportunities for learning and strengthens the connections between members.

Building a sense of community is important for online learning, as learners can readily drift away or feel isolated due to the nature of online engagement. It is therefore important that you take steps to keep students together and engaged. This might involve reminding them of what they are supposed to be working on at any given time. Drawing on the concept of communities of practice, the university can emphasise that connecting and sharing with like-minded others can be very beneficial.

Educators may find that they spend less time engaging with students through lectures or traditional sessions because the material is presented in a form that students can access independently at any time. In an online environment, the role of the educator can become more supportive and collegiate, making students aware that their teacher’s primary role is to help them to succeed on the course. To this end, it can be useful for educators to construct an individual relationship with each student rather than always relying on mass or automated emails.

Activity 3.3 Benefitting from a community of practice

Now that you have reflected on your engagement (or lack of engagement) with the course community of practice, decide how you would like to engage with it from this session onwards.

Comment

Members of a community of practice often engage with the community for a variety of purposes. Sometimes their activities are purely social or purely academic, and sometimes they include a mixture of different activities. Research has shown that when the community is engaged with a balance of different activities, the members benefit the most. Therefore, try to engage with both social and academic/practice-related activities of your course community of practice.

If you have time, and this is a subject that interests you, follow this link to learn more about communities of practice.

2 Educational theories that can help take teaching online

When referring to online education and its advantages for learners, three theories are often discussed. These are behaviourism, cognitivism and constructivism. You do not need to delve deeply into any of these theories, but it is useful to bear in mind the general ideas behind them when considering a move to an online or blended teaching environment.

2.1 Behaviourism

Skinner (1968) and Thorndike (1928) were two of the main proponents of behaviourism. Their work examined how behaviour is linked to experience and reward. In the online education context, educators should be aware of the benefits of ‘rewarding’ their students for positive behaviour. One way of doing this is via the assessed elements of the course. Grades, digital badges, records of progress, certificates and qualifications can all be used to mark achievement. Another approach is to offer encouragement and positive feedback for activities such as engaging in discussion or reaching certain milestones.

2.2 Cognitivism

Cognitivism largely replaced behaviourism as a theory of education and concentrated on the organisation of knowledge, information processing and decision making. Bruner (1966) suggested that learners should be given opportunities to discover for themselves relationships that are inherent in the learning material, a teaching technique he named ‘scaffolding’. In an online learning environment, this could mean, for example, educators providing regular and focused support to students in the early stages of a course but making less frequent supporting interventions as the students begin to act successfully by themselves.

Ausubel’s work (1960) indicated that it is better to provide some materials in advance, enabling learners to organise their learning approach, so that once the course begins they have already developed much of the skillset they will need to undertake it successfully.

2.3 Constructivism

Constructivism is concerned with how knowledge is constructed. The main proponents of constructivism were Piaget (1957) and Vygotsky (1986). Piaget was interested in how knowledge is constructed by the individual, and in particular, how children move through several different stages of development in terms of constructing knowledge.

Vygotsky, who wrote in the 1920s and 1930s and was translated into English several decades later, was more concerned with the important role that the social construction of knowledge has to play in this process. With respect to online education, one of the important notions to take from Vygotsky’s work is the ‘zone of proximal development’, or ZPD. In short, this suggests that learners progress best if they are continually presented with tasks that are just beyond (i.e. proximal to) their current zone of ability or development. If tasks are too simple, boredom ensues, and, for example, a student may drop out of a course. If tasks are too advanced, enthusiasm can be lost, frustration builds and again, the student may lose interest.

Vygotsky suggested that the tasks in that zone of proximal development are ones that most learners can achieve with just a little help – which is where the role of the online educator is vital. Some of the ways in which an educator can offer support and challenge are different from those used in face-to-face settings, as this course will explain.

Activity 3.4 How do educational theories match with your practice?

Make brief notes on the differences between behaviourism, cognitivism and constructivism. Are there ideas that are present in your current practice? How do they appear? Do these theories fit with your experiences of learning in general and your learning on this course?

Comment

If you are an educator you are probably familiar with these theories already, but it can be helpful to take a step back and look at your practice with a critical eye. This activity should help you to identify where you draw on the theories. As you move through the course, this should also help you to decide where the theories will play a role in your online practice.

In this section you have explored some of the theories that inform the underpinning principles of effective online teaching. However, online education cannot take place without the application of technology, and this is what you will focus on next.

3 Digital technologies for online teaching

This section of Session 3 gives an overview of the possible technologies available in an online education setting and the ways in which they can support and influence teaching and learning.

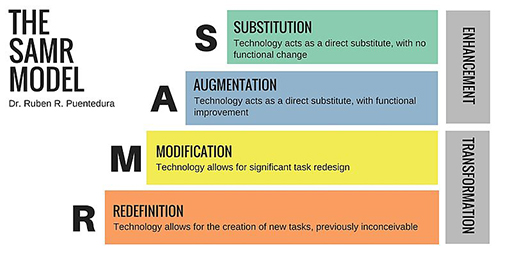

The SAMR model categorises four ways in which the introduction of technology changes teaching activity (Puentedura, 2017):

- Substitution: Technology is used as a direct substitute for what was done in the past, with no functional change.

- Augmentation: Technology is a direct substitute, but there is functional improvement over what was done without the technology.

- Modification: Technology makes it possible to redesign the task significantly.

- Redefinition: Technology makes it possible to do things that were previously not possible.

As Figure 3.4 shows, the first two ways of using technology for online education lead to an enhancement of the teaching practice and potentially the learning experience, while the other two ways (modification and redefinition) lead to the transformation of the teaching practice.

There has been substantial debate about the value of, and evidence for, the SAMR model (for example Love, 2015). However, the model has achieved some popularity among researchers and practitioners. Here, it is used as a way to categorise four ways in which technology can be introduced into online education. If you have time, you may wish to explore some of the discussions about the value of this model, starting by following the references in brackets above (full versions of references are provided at the end of each session).

The following sections describe different groups of tools that are commonly used in online education.

3.1 Learning management systems

Online courses and courses with any online component are usually delivered using a host platform, commonly referred to as a learning management system (LMS) or virtual learning environment (VLE). These systems (Moodle and Blackboard are popular examples) support the delivery of materials to students, keep track of registered students, and support other tasks such as assessment and communications.

Educators based in traditional universities and colleges will not normally have much input into the selection process when their institution is investing in one of these systems (even ‘free’ LMS systems such as Moodle require investment in terms of adapting and running the product). Usually the role of educators and collaborators/support staff is to find out what possibilities exist for teaching online using the product, and to use the elements that seem most productive in their individual context.

A variety of tools can typically be included, such as e-books, blogs and wikis, quizzes and automated assessment processes, spaces for synchronous and asynchronous learning activities, and repositories for learning objects. The ways in which LMS tools can be used in teaching are covered in more detail in the next session.

3.2 Content creation tools

With online learning comes the potential to use a variety of media and to use content creation tools to package them all together to form a coherent learning experience. As well as providing interesting ways to use audio and video in teaching, leading and/or supporting learning, there are online tools available that support the production of graphs and infographics, animations, storyboards and more.

Whatever your role, it is useful to browse and trial a range of software (with a variety of media and presentation formats) to discover which kinds would help bring online education at the university alive. Session 4 of the course provides some guidance on this process. When you have an idea of what you want to create, or want others to create, you will need to identify how the outputs that can be created with these tools can be integrated with the learning management system to create a dynamic and engaging online learning experience.

In addition, you may enable students to use these tools in their online work. Beetham (2007) points out that:

‘Applications can even be shared to enable collaborative representations to be built, as happens face to face with electronic whiteboards, and with wikis online. Learners’ representations can of course be used for assessment but they can also be re-integrated into the learning situation for reflection and peer review, or even as learning materials for future cohorts.’

3.3 Networking and collaboration tools

Google Docs and other elements of the Google Workspace (as well as similar tools such as Padlet) allow educators to share materials with their students and work on them together in real time, or asynchronously. This can strengthen the teacher-student online relationship, which is particularly valuable in the early stages of a course. In addition, a range of collaborative networking tools can be used to foster group working and a sense of community between students on an online course.

Instant messaging apps can be used to support backchannels (Session 2 of this course introduced backchannels). Activities using Twitter or Pinterest to search for information, or Diigo to gather together relevant internet bookmarks, can help bring an online group together with a shared objective, as well as exposing that group to a wider community in a relevant subject area.

3.4 Enhancing existing tools and materials

You may already be used to creating Word documents and PowerPoint presentations, or be familiar with similar word processing and presentation software. Materials in both formats can be repurposed for the online environment. They are a classic example of the ‘substitution category’ of the SAMR model (Puentedura, 2017) where methods used in a face-to-face environment are moved directly online.

With a little more work, static documents featuring text and images can be turned into online exploration tools, linking to websites, animations, videos, blogs and so on to enrich the learning experience. These improved files can then be integrated with other materials using content creation tools, or mounted within an LMS, for example. The next session will cover the practicalities of doing this.

4 This session’s quiz

Check what you have learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab, then return to this session when you’re done.

Summary

In this session you have looked at the core theories and principles that underpin effective online teaching and started to look at the digital technologies involved. In Session 4 you will look in more detail at the technologies that can be used to deliver online education.

Finally, this week, let’s see how Rita’s getting along.

Activity 3.5 Reflecting on progress

Watch the video or read the transcript. In it, Rita reflects on Session 3 from her perspective as an educator. Take some time to make notes on the following questions:

- How does what you have learned in this session relate to your own role?

- What changes, if any, could you make to your practice or to the wider practice at your university as a result of what you have learned?

Transcript

You can now go to Session 4.