Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 21 February 2026, 9:51 AM

Session 4 Selecting technologies

Introduction

This session provides an overview of the main tools available for creating digital content, what they offer, and how they can be used to support and facilitate online learning. It does not aim to be (and could never be) comprehensive, but it includes a selection of online resources that you may find useful for further exploration. It also includes some categorisations of these tools that you can use to understand the potential of some of the main types of tools for your own context. There are multiple blog posts, categorisations, discussions and sales pitches on the internet that relate to these tools. This session gives you a starting point from which to navigate these tools and use them to your advantage.

A note on privacy and personal information, which is particularly relevant if you are registering for and trying out different tools. If you are concerned by the privacy implications of using some of the tools covered in these materials, one approach is to use an alias when creating your account with them, and to create a separate email address (for example using Gmail) for the purpose of registering for the service instead of using your university email address. However, this approach will not make your actions truly anonymous or private – the service provider or your own internet service provider (ISP) will be able to identify that it is your computer accessing the service. It is possible to take further steps such as browsing in private or using an anonymous surfing mode. Most browsers offer this feature. For example, in Google Chrome, Incognito enables anonymous browsing; in Firefox, and Microsoft Edge, it is called private browsing. However, discussion of the pros and cons of such techniques is beyond the scope of this course.

Practitioner reflections

This session begins with a video from Sarah, who explains how she decides on the tools she uses to teach her nursing students. Before watching the video or reading the transcript, reflect on what you consider when you choose a tool, an application or a new technology to support students or other staff. As you watch the video or read the transcript, make a note of the decisions that Sarah mentions and whether these decisions would involve managers, educators, collaborators/support staff or a combination of these groups.

Transcript

[WRITTEN QUESTION] How did you learn to choose between tools?

Learning outcomes

By the end of this session, you should be able to:

- find, evaluate, manage, curate, organise and share digital content for learning, teaching and assessment

- produce digital materials in a variety of formats;

- design digital activities for different contexts;

- take into account issues such as accessibility, usability and openness;

- investigate and implement new digital approaches to learning, teaching and assessment;

- use digital tools to plan, design and review courses of study;

- use digital tools to plan and reflect on learning and support learners or other staff to do the same.

1 Technologies for content creation

With online or blended education comes the potential to use a variety of content creation or editing tools, applications and technologies. These enable production and presentation of learning content in a variety of formats, including videos, audios, graphs, animations and digital stories. These make it possible to turn static documents featuring text and images into online exploration tools, linking to websites, animations, videos and other resources to enrich and enliven the learning experience.

So many technologies could be used for content creation that it is impossible to cover them all. New tools are produced frequently, and older ones disappear, so specific examples can become outdated very quickly. What follows is an overview of the kinds of tools available and some brief guidance about things to be aware of when using or selecting them.

Before moving on to the next section, consider the ways in which text can be used to create digital content. In classrooms, text is used for printed handouts or longer pieces for preparatory reading. In online contexts, using a lot of continuous text is not advisable because reading from a screen is tiring and can rapidly become boring. Therefore:

- write in short sections, using subheadings;

- vary your writing style to make the learning experience more enjoyable;

- use visual elements such as photos, diagrams, images, bulleted lists, tables, boxes and quotations to break up the text;

- include short questions that will make learners pause and think before they move on;

- provide summaries or supporting material in text, especially if there are problems with intermittent or limited internet connection.

1.1 Repurposing and extending slide presentations

Presentation tools such as PowerPoint and Microsoft Sway contain features for enhancing content presentation, for example by adding narration to a slideshow or adding sound clips to individual slides. These features mean that synchronous online slideshows can be repurposed for an asynchronous online audience.

You can choose to make a continuous recording of your narration or you can add sound clips to individual slides. One advantage of individual sound clips is that learners can choose when to begin listening – for example, they may wish to read the content of the slide first. Similarly, a vision-impaired learner using a screen reading program can listen to the text being read aloud before selecting the audio clip.

By contrast, a single narration file across the entire slideshow forces learners to pause the narration if they cannot read and listen to everything in the time you allow before moving on. Users of screen readers will hear the text being read aloud by their assistive technology at the same time as your narration, which can be confusing.

If you would like to share presentations online, services such as Slideshare make this a straightforward process.

Tip

Use a good quality microphone to ensure clear sound. These are usually inexpensive, but the increase in output quality makes investing in this equipment worthwhile.

1.2 Screencasting

A screencast is a recording of what you are doing on a computer screen, with a voiceover, which is then published online or sent to your audience. It is ideal for demonstrations where viewers benefit from seeing something being done. Learners can replay screencasts as often as they wish and can pause and rewind them.

Free screencasting tools, and free trials of paid-for tools, are available, although these may be limited in terms of the length of recording that can be produced, and sometimes the finished recordings contain a watermark ‘advertising’ the tool used. Paid-for tools offer a much greater range of features and flexibility in output. Try these out first and see if it would be worthwhile to purchase a licence. Camtasia and Adobe Presenter are examples of paid-for tools, both of which offer a free trial at the time of writing. Wikipedia hosts a list of screencasting software that includes many free and paid-for tools.

Tip

Screencasts can quickly grow to very large file sizes because they capture both audio and visuals. A number of short clips will download or buffer more quickly than one long clip and are a better option when learners do not have reliable access to high-speed internet.

Activity 4.1 Demonstrations of screencasting

Watch these two short screencasts. The first provides tips for using photo editing software, and the second demonstrates how to screencast using Google Meet.

It is not the subject matter of these clips that you need to note here, but the possibilities for your context. Are there are any elements of your work that might be explained or demonstrated effectively through screencasts? Make a note of some ideas for suitable topics in your own department.

Screencast 1: Quick tips in Photoshop Lightroom

Transcript

Screencast 2: How to screencast with Google Meet

Transcript

Comment

Screencasts can be very effective for explaining or demonstrating certain concepts or topics. This activity should prompt some thoughts about elements of your own work that might make good subject matter for screencasts. Screencasts vary depending on the subject matter; if you think there is potential in your context, then we recommend trialling some of the software listed as this can be a very powerful tool.

A related approach of sharing the screen during a ‘live’ video call is possible using many modern video conferencing tools. However, if this is not recorded it would not be available for later use in the way that these screencasts are.

1.3 Low-tech, low-complexity video recording

You may be able to find existing videos available on the internet to incorporate in digital content or presentations, but you may also want or need to make your own. This does not need to be complicated, nor require sophisticated equipment. A simple set-up with a phone camera and a tripod can work well.

In the following activity, Pauline gives some practical tips about how to make short videos.

Activity 4.2 Low-complexity uses of video

This video highlights the benefits of a low-tech, low-complexity approach to producing video content in online teaching.

- Watch the video or read the transcript and make notes about how achievable and effective this method could be in delivering your digital content.

- Pauline has shared some tips about her practice. Consider whether you have tips about use of video in your context. If so, share them in the course community of practice Facebook group and take a look at any tips shared by others. If you have not joined the community of practice Facebook group, you could discuss these ideas with colleagues within your university.

Transcript

Comment

It is important to emphasise that video does not need to be an expensive, high-tech venture. This activity is designed to demonstrate how achievable video can be for many educators and those who support or lead online education, and to help you to think about how it might be useful in your own practice.

To demonstrate how effective low-tech videos can be, the ‘practitioner reflections’ videos used throughout this course were all made by the people speaking, at home, using regular webcams or phone cameras.

Tip

Even with low-tech approaches to video, certain techniques can make a big difference to the quality and effectiveness of your clips. Keep the camera stable by placing it on a firm surface or using a tripod. Be aware of distracting elements in the background. These could include screens, people or animals moving around, or personal items such as family photographs.

1.4 Image manipulation

Images can be used to great effect in an online or blended learning experience. They can illustrate a concept, provide emotional impact, reinforce learning, or simply add visual decoration.

Rather than including images only in their original form, try using free graphics software to manipulate and annotate images. For example, a teacher could digitally alter one image and post it side by side with the original, asking learners to ‘spot the differences’, or obscure elements of an image and ask learners to predict what is hidden (this method works especially well with mathematical or chemical equations).

Images can also be used to:

- support communications with students or other staff;

- provide additional non-textual information;

- save time when creating digital content;

- help students or staff remember the material better and sometimes inspire them to act.

Tip

Ensure that the resolution and file sizes of your images are appropriate. If the resolution is too low, details may not be sufficiently clear, especially for students using certain displays or magnification software. Conversely, images with a very high resolution can mean huge file sizes that take a long time to download for anyone with a slower internet connection.

File sizes can be checked by looking at the ‘properties’ of the file in your computer’s file manager. While software tools all differ, there are generally options when saving a file that allow resolution or quality to be changed. Also ensure that you have provided a description of the image so that students unable to view it can still understand what is being depicted (you will learn more about making online education more accessible and inclusive in Session 7).

1.5 Small interactive tools with big impact

Tools that make it possible to add interactive items to web pages, such as word clouds, quizzes and drag-and-drop exercises are all freely available on the internet. If you have an idea for an online activity that you would like to try, the chances are that there will be a tool somewhere to help you to achieve it.

Lists and comparisons of different tools are available if you search using terms such as ‘online interactive tools’. For example, this is a list from a research-based educational organisation.

Tip

Some of these tools use browser plug-ins that add the ability to use technologies such as Java to generate content for you. If this is the case, you and your students will need up-to-date Java installations for these websites to work properly.

It is worth checking whether the interactive components work well on different kinds of browsers or platforms. For example, do they work on Google Chrome, Safari and Opera, and on a tablet or smartphone?

1.6 E-learning development tools

Creating engaging teaching content using the tools outlined in this section should be within the capability of most people who are digitally literate. However, there are more complex tools available that can help you to generate comprehensive, multimedia, interactive online digital content. If you are interested in immersing yourself in new tools and techniques for content creation, you might try different authoring tools.

A web search for ‘e-learning authoring tools’ will bring up a range of current technologies you could try. At the time of writing, popular tools include Adobe Captivate, Articulate Storyline, Xerte Online Toolkits (free), Canvas, OpenLearn Create (free), EdApp, iSpring and more – new tools emerge every year.

1.7 Web conferencing platforms

Most higher education institutions have invested in at least one learning platform with web conferencing functionality to support online and blended learning. You may have heard of Adobe Connect, Microsoft Teams and Blackboard Collaborate, for example, but there are many similar products available, including tools designed for individual use such as Skype, Zoom or Google Meet (formerly Hangouts). These applications provide opportunities for online teaching scenarios, as well as screensharing, group work, peer review and more.

The greatest strengths of such applications tend to be in synchronous learning or collaboration, although they can also be readily combined with tools such as discussion forums to broaden their impact to asynchronous environments (Çakiroglu et al., 2016; Guo & Möllering, 2016; Kear et al., 2012). These tools can be used to replicate a seminar environment by wrapping synchronous discussion tools around a central presentation or video with voiceover.

1.8 Plagiarism detection

Plagiarism detection software is perhaps not a technology you would immediately think of as an online teaching or support aid. However, plagiarism prevention tools (which automatically compare assignments from students with each other, and with content found online) can be used to meet certain learning objectives in an online environment.

Many institutions now provide staff and students with access to a plagiarism detection service. This can be employed to illustrate to learners how to write or compile assessment material in an appropriate manner, how to build on (rather than repeat) previous work, and how to reference and quote appropriately. In this way, these tools can be used to offer formative feedback rather than just being used to identify problematic assessment submissions.

If you would like to know more, the first step is to find out whether there are tools already in use at your institution. If not, or if you are considering changing to use another tool, Wikipedia hosts a list of plagiarism detection software.

There are potential problems when introducing plagiarism software. One is that the software cannot tell the difference between accidental and deliberate plagiarism. This can lead to assumed guilt where the problem is simply poor academic practice. In many cases, the most appropriate response is to provide students with additional support in referencing.

There are also concerns about whether the storage of intellectual property, such as an essay, in a plagiarism company’s databases is ethical if the author has not agreed to it or is unaware of it. Students should be aware that the technology is being used and should have opportunities to explore how it can be used to support their learning.

2 Personalisation with tools for learning

Personalisation is the tailoring of digital materials and the environment in which they are delivered to suit the needs and preferences of a range of learners. It links closely to accessibility for learners with disabilities, and you will examine this aspect in more detail in Session 7. This session considers how technology can be used to support the whole range of learners, whatever their needs or preferences.

Online education usually has more opportunities for personalisation than face-to-face delivery, simply because it is easier for learners to use the available technology to modify their learning environment to suit their needs. Consider, for example, how easy it is to dim a computer screen, compared to the difficulties in dimming a classroom environment without inconveniencing other learners.

Asynchronous online learning usually has more opportunities for personalisation than synchronous learning because it gives learners flexibility in terms of when and where they access the learning materials.

Optimising personalisation in online education has two elements:

- designing digital materials that will meet a wide group of needs and preferences using a variety of media and teaching techniques;

- putting control in the hands of each learner, allowing them to adjust the materials to suit themselves.

2.1 Serving diverse audiences

It is worthwhile to design digital materials and use technologies for as broad a range of learners as possible. By doing this, materials are ready to be reused in later years or different contexts. This section provides some general guidelines, so that you can consider how these considerations would be applied to your own context. Session 7 covers this area in greater detail.

Instructions

Clarity is important when designing and delivering materials for a wide range of audience needs. Ensure instructions are clear, unambiguous and consistent in the use of terminology (Ernest et al., 2013). When producing audio or audio-visual materials, speak slowly and clearly, including pauses that allow learners to understand and note key sentences or phrases.

Cultural references

Be aware that those accessing the material may not all share the same cultural backgrounds and reference points. This means the use of idioms or cultural references in digital materials must be considered carefully (Arbour et al., 2015). Similarly, the choice of images or videos must reflect diversity fully.

Flexibility of schedule

It is vital to provide learners with a schedule of key dates and deadlines, and to ensure at regular intervals that they are aware of what is immediately ahead of them. At the same time, flexibility should be designed in where possible. If there is not a strict need for every learner to complete a certain task at the same time, then allow extra time for those who need it. Some learners may need individual attention in order to keep to the overall schedule – this is another element of personalisation (Ernest et al., 2013).

Communication and peer support

Online learners should be encouraged to comment and reflect on their learning. This may be achieved using their own spaces, such as blogs, or more public spaces, such as discussion forums. Asynchronous forums allow everyone the chance to input on their own terms and at their own pace, while discussing and commenting on each other’s posts.

These interactions, if supported and moderated appropriately, can help to foster a sense of community among the learners. This can, in turn, lead to the development of peer support. Peer support is a key aspect of personalisation, as it allows learners to explore and learn as a collective, with each member of the collective playing to their own strengths.

2.2 Giving control to learners

It may sound like a complicated process, but there are several ways of giving control to learners that involve little extra work to develop.

Allow choice of formats

It is standard accessibility practice to provide transcripts for audio or audio-visual materials, to provide captions for video materials, and to provide alternative text for images. These alternative formats are used by a wide range of people, not only those who have reported a disability, so these format options should be available as standard (Fidaldo & Thormann, 2017). Similarly, some learners may prefer to receive feedback as an audio mp3 rather than written text. This audio feedback can be quicker to produce than text-based feedback.

Allow a choice of display characteristics

Many digital materials – including web pages, documents and slideshow presentations – can be easily altered by users to suit their needs in terms of font, font size, colour and contrast. Make it clear to learners how they can personalise study materials. One way of doing this is to provide links to guidance pages on the internet that describe how to use built-in web browser features to achieve these changes.

3 Technologies for social communication

As you saw in the Session 2 section that discussed backchannels, social media can have an important role in online education. A variety of social media tools can be employed in online teaching and learning, each with its own advantages and drawbacks.

A phased approach to the use of social media tools in online education is often useful. Students may be very familiar with social media without knowing how to use it to support their learning. Twitter and YouTube can both be used to great effect in demonstrating how public commenting can easily move away from ‘constructive’ feedback and in an unhealthy direction.

Skills in providing constructive feedback can be developed in a relatively closed environment. For example, students might be supported in their use of a discussion forum, commenting first on an educator-provided item, and later on each other’s contributions. When they know how to make constructive contributions, discussion can be moved to a more public arena (Jones & Gallen, 2016).

If you would like to read more about the positive and negative effects of using social media in teaching, an online search using the phrase ‘effects of social media on student engagement’ will point to a variety of literature on the subject. This shows that using social media appears to have a significant effect on student engagement, but – in some circumstances – it may have negative effects on student attainment.

For educators and those leading or supporting learning, social media can be a useful tool for connecting with others working in the field locally, regionally, nationally and worldwide.

3.1 Social technologies for promoting community

Some social media tools can be used to enhance communication and cohesion among a group of online learners. Some examples are:

- Collection tools such as Pinterest can help learners discover a topic collectively and share their findings or ideas.

- Social bookmarking tools such as Diigo can broaden learners’ research skills, connecting them with resources they had not previously discovered.

- Content curation tools such as Scoop.it allow learners to create boards of curated content and to share their thoughts on that content, while connecting with others who have similar interests.

Simply using appropriate technologies will not force a sense of community and shared learning to develop in any given cohort, but it will give it a chance of happening. If Facebook is available to all members of a cohort, the creation of a class Facebook group can give learners an easy way to communicate with each other, as well as providing educators and collaborators/support staff with an opportunity to provide prompt scheduling reminders, and to share relevant resources. Coughlan and Perryman (2015) have written about the use of student-led Facebook groups and their role in facilitating learning and achieving educational inclusion.

3.2 Social technologies for enhancing online presence

Some social media tools can be used in online education to help staff develop a sense of place within the ‘wider world’ and to enhance their online profile (Veletsianos, 2016). Blogs and vlogs (video blogs) can help learners to reflect critically on a given topic and become familiar with expressing themselves in a public arena. They also mean explanatory text can be shared alongside class materials, providing greater context for learners who are catching up or revising. Twitter can be used to demonstrate the power of the collective, to share discovered resources, to seek feedback, and to contact experts in a given subject area. Uses of social media are explored in more detail in Session 5.

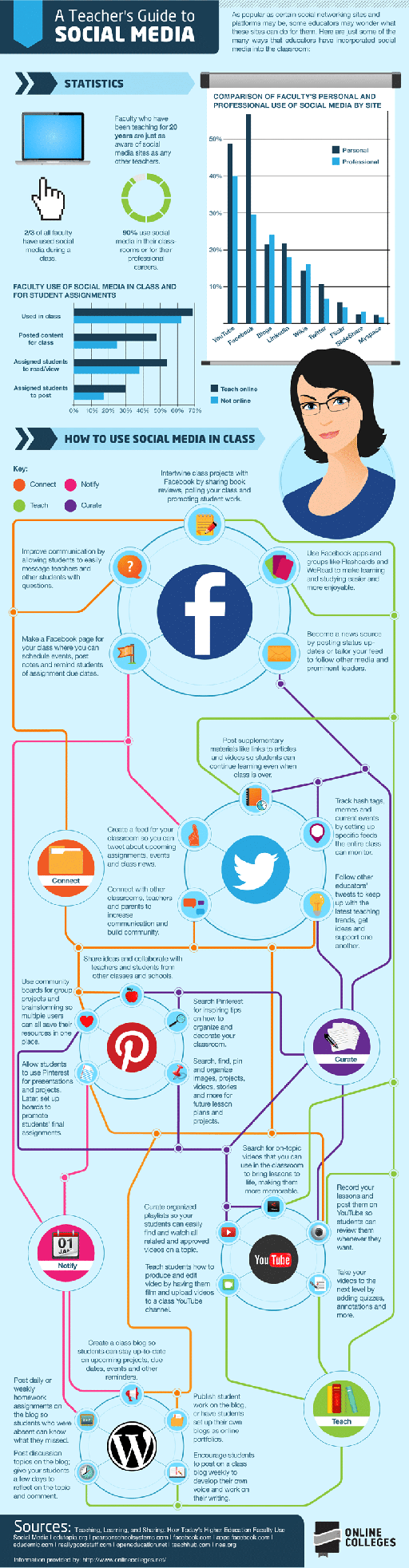

Activity 4.3 Social media in online education

Take a look at this infographic, which provides a wide range of suggestions for ways in which social media can be used in education. (You should be able to click on the image to zoom in.)

Drawing on the materials in Section 3, write down two to three ideas you might try in the future. What factors might you need to consider when implementing social media tools?

Comment

Social media tools can be useful in teaching, even though they may require careful implementation. This activity is designed to get you thinking about how social media could play a role in your online education, and what factors you need to consider when implementing social media tools.

4 Tools in a changing technology sector

Change is an ever-present topic of conversation in education, and particularly with respect to technology.

The rapid and constant evolution of technology means that some of the online education tools you read about today will have disappeared in a year, while new ones will become available. However, the principles for selecting these tools to achieve online learning objectives will remain the same.

Before making substantial use of a tool, or committing to purchasing it, consider whether it has a substantial user base, and the developer or supplier’s model for sustainability, support and improvement.

A number of factors will influence tool selection (Watson, 2011), including – but not limited to – the following:

- Intended learning outcomes for the course. Technology must serve the pedagogical outcomes, not determine them.

- Students’ situations. This reflects issues such as location and internet access.

- Activities and technical requirements of course content. These might include use of large graphic files, collaborative tools, live chat features, external guest lecturer access, file sharing and discussions.

- Breadth and depth of the teacher’s previous online experience. The best approach is to start slowly and build experience and confidence. Introduce one component, use it appropriately, evaluate its success, and then adjust teaching practice where necessary. Slowly introduce more components when everyone is comfortable with the technology.

- Requirements or policies of the institution regarding the use of different online technologies.

- Whether a centralised learning management system (LMS) is available or free, open web technology is preferred.

- Cost. This includes cost to individuals and the university, both directly in purchase costs and indirectly in the amount of time needed to become competent in usage of the tool.

If you would like to read more about technology and tools for online learning, JISC (2016) has created a resource that combines guidance with case studies and includes a useful checklist.

4.1 Linking learning outcomes, activities and tools

The University of New South Wales Sydney (2017) provides a very useful table that groups common themes of learning outcomes, the kinds of activities often used with learners to achieve those outcomes, and potentially useful online technologies for each. An edited version of this table forms the basis for Activity 4.4 below.

Activity 4.4 Identifying technologies that you might use

Read the activity tasks below and then complete them using the table that follows. The column on the far right of the table identifies different tools, while the other columns address desired learning outcomes, rationale for use and relevant activities.

- Which tools and associated practices shown in the table do you or your students currently use in a teaching/learning context? Spend a few minutes making a list.

- Outside the teaching environment, which tools are your students likely to use to express themselves, to reflect, to explore and to have fun? Again, make a list.

- Put an asterisk by each tool on your lists that you would describe as social.

Comment

This activity should help you to develop your ideas further – now you should be able to match possible tools to the tasks you wish your students to achieve online. You will build upon these ideas in later sessions.

| Desired learning outcomes (‘what?’) | Rationale (‘why?’) | Relevant activities (‘how?’) | Potential technological tools |

|---|---|---|---|

Information literacy. Global practice. Digital literacy. Ethical practice. Preparation for success. | Exposure to, awareness of, contribution to external:

Appropriate referencing. Appropriate equipment of the 21st-century graduate. Managing information load. | Multidimensional evaluation. Sharing and reviewing online resources. Connecting with outside experts/communities. Checking for plagiarism. Media making/mash-ups. Digital storytelling. Copyright/Creative Commons discussions. Activities relevant and authentic to discipline. Embedded activities for generic attributes. Contextual prompts to evaluate sources. | RSS feeds/aggregators. Blogs. Plagiarism prevention (e.g. Turnitin). Presentation sharing (e.g. SlideShare). Video sharing (e.g. YouTube, Vimeo). Podcasting. Online/distance learning platforms (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect). Screencasting. |

Self-directed learning. Reflective practice. Engaged learning. Co-learning. Quality learning environment and experience. | Negotiate understanding. Feedback on the course. Reflection on learning. Global practice. Consistency of experience. | Problem/case-based learning. Flexible access to material. Project planning and management. Student self-tests. Teacher (and technology) as facilitator of learning. Choice of modes and activities. Access to technology (e.g. mobile devices). Agreed code of conduct. | Wikis. Quiz/survey. Recorded lectures. Video sharing (e.g. YouTube, Vimeo). Podcasting. Mobile learning (e.g. smartphone, tablet). Online/distance learning platforms (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect). |

Giving and receiving feedback. | Multiple perspectives. Feedback on performance. | Collaborative writing. Group negotiation and planning. Assessment of teamwork. Reviewing (e.g. group work). Publishing. Reflection. | Wikis. Blogs. Discussion forum. Peer review (e.g. via forums). Online/distance learning platforms (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect). Screencasting. |

Working in teams. Collaborative practice. | Negotiating understanding. Multiple perspectives (for teacher). Management of group work. Digital literacy. Inclusivity. | Collaborative writing. Group negotiation and planning. Project planning and management. Problem/case-based learning. Assessing team contribution. Media-based projects. Variety of communication styles supported. | Wikis. Blogs. Peer review (e.g. via forums,). Collaborative word processing software (e.g. Google Docs). Online/distance learning platforms (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect). Moderated discussion. |

Critical reviewing. Critical thinking. Independent learning. | Negotiating understanding. Multiple perspectives. Feedback. Practice of critical reviewing. Practice of critical thinking. | Reflecting. Debating. Reviewing. Social knowledge building. Review of/ commentary on online material. Giving and receiving feedback. | Blogs. Discussion forum. Online/distance learning platforms (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect). Seminar replicators (e.g. VoiceThread). Video sharing (e.g. YouTube, Vimeo). Podcasting. RSS feeds/aggregators. Peer review (e.g. via forums). |

Synthesis of learning. Applying learning (at high level). | Able to solve new problems. Application of knowledge in integrated way. | Experiencing ‘authentic’ practice. Integrative (could be group) project. Problem/case-based learning activities. | Authentic voice via video/audio. Online/distance learning platforms (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect). Simulations e.g. virtual experiments. Animations. |

Written communication. | Negotiating understanding. Contributing to external activity, conversations, resources. Appropriate referencing. | Reflecting. Debating. Reviewing. Publishing. Checking for plagiarism. | Blogs. Discussion forum. Plagiarism prevention (e.g. Turnitin). Presentation sharing (e.g. SlideShare). Messaging (e.g. Twitter, Yammer). RSS feeds/aggregators. |

Oral communication. Presentation skills. Language proficiency. | Sharing audio/video material. Presenting. Digital storytelling. Audio/video discussion and feedback. | Seminar replicators (e.g. VoiceThread). Video sharing (e.g. YouTube, Vimeo). Podcasting. Presentation sharing (e.g. SlideShare). Online/distance learning platforms (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect). Screencasting. |

Activity 4.5 Selecting tools

Think back to the activities in the previous sessions and retrieve your notes about what you want to deliver online and what kinds of tools you would need to employ to achieve this. Consider:

- Which tools from your lists map across to some of your desired objectives in teaching online?

- Which objectives do not have an already-used tool mapped across to them?

- Have you discovered anything in this week’s materials that might help you meet these objectives?

Comment

Activity 4.5 should help you to develop further your responses from previous sessions – now you should be able to match possible tools to the tasks you wish your students to achieve online.

5 Badge quiz

In this badge quiz, you will check what you have learned in Part 1 (Sessions 1–4) of the course. You must obtain a score of at least 50% to qualify for the badge.

Remember, this quiz also counts towards your final badge and certificate of completion.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab, then return to this session when you’re done.

Summary

In this session you have learned about many different tools and technologies – including social media – that can be used in online education.

In the next session you will look at another side of social media’s role in online education – the role of facilitating the creation and development of your own networks.

While you contemplate all of the tools and technologies covered in this session, let’s see how Rita has been coping with all this useful information.

Activity 4.6 Reflecting on progress

Watch the video or read the transcript. In it, Rita reflects on Session 4 from her perspective as an educator. Take some time to make notes on the following questions:

- How does what you have learned in this session relate to your own role?

- What changes, if any, could you make to your practice or to the wider practice at your university as a result of what you have learned?

Transcript

You can now go to Session 5.