Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 8 February 2026, 9:26 PM

5 Working with the diversity of the trans community

5 Working with the diversity of the trans community

Trans people are a diverse group and there is no one story or experience that holds true for everyone. In the next section, we focus on three types of experiences that the ICTA data suggest are important for therapists to be aware of when considering this diversity.

It might not be (just) about being trans

All of us have multiple, overlapping identities. ICTA researched specific groups that might have additional marginalisations within trans healthcare or were otherwise overlooked. Overall, the study found that these other identities could further complicate the trans healthcare experience. This finding is in line with the concept of intersectionality.

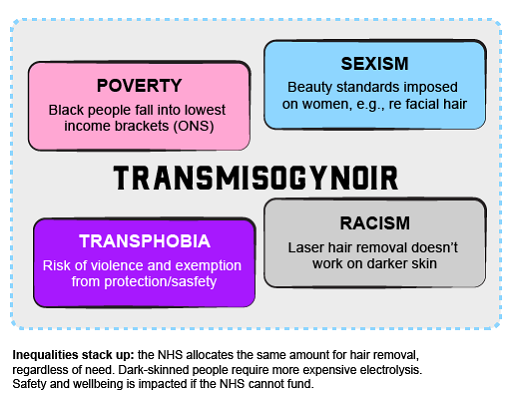

‘Intersectionality’ is a term coined and developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1993). It can be defined as an analytical framework that describes how a person can experience discrimination that is specifically produced by a combination of two or more social categorisations, such as class, race, sexuality, gender identity and disability. An example of this would be how black trans woman experience a combination of racism, sexism and transphobia; this is termed ‘transmisogynoir’ (Krell, 2017) to indicate the way in which these factors combine and cannot be treated separately.

Find out more about the ICTA study findings by doing the next activity.

Activity 5.1: Extra barriers faced by some trans people

Activity 5.1: Extra barriers faced by some trans people

Consider the ways in which more marginalised trans people may face extra difficulties by pairing the following statements. As you engage in the activity, consider what the impact of these additional difficulties might be for counselling with such clients. Drag and drop each of the statements into the relevant cell in the table. Alternatively, you can download the accessible PDF version below.

Discussion

The ICTA project specifically explored the experiences of trans people living in rural locations and trans people with low income and/or low educational attainment, Black trans people and trans People of Colour, disabled trans people and trans people with chronic illness, and older trans people. ICTA also found additional discrimination for neurodivergent (e.g., autistic) trans people and those with mental health problems. In particular, participants with mental health problems talked about their experiences of being seen as not mentally stable enough to transition even if a significant cause of their mental health difficulties was not being able to transition.

5.1 Co-occurring issues and how we view them

There is empirical evidence of co-occurrence between being trans and having certain other differences and diagnoses and being diverse in other ways. To explore this further, try the next activity.

Activity 5.2: Reflecting on co-occurrence and causality

Activity 5.2: Reflecting on co-occurrence and causality

Part 1

A client comes into your therapy room. Over the course of the next hour, you discover five facts about him – for each fact, tick which statements you believe apply. Alternatively, you can download the accessible PDF version below.

Discussion

This client profile is based on Alan Turing, arguably the greatest contributor to the modern computer age. You are invited to make note of the way you responded to each of Turing’s differences:

- Did you think about what ‘caused’ Turing’s genius, or his left-handedness?

- What assumptions are you making about what ‘caused’ his sexuality and his autism?

- Do the answers reflect how positively or negatively society thinks about these differences?

- When you saw all these differences together in one person, did you find yourself wondering about what linked them all?

- If Turing had been trans, would that have changed any of your answers?

Turing is a good example of a cluster phenomenon that is just beginning to be observed – divergent people may be divergent in multiple ways. This cluster phenomenon is explored in the following reading.

To find out more about this issue of co-occurring traits, listen to this excerpt from Person-Centred Counselling for Trans and Gender Diverse People, read by author Sam Hope:

Transcript

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection

Although the reading discussed a number of different population overlaps, the autism/trans overlap is perhaps the most commonly discussed and researched (Glidden at al., 2015). Our ICTA research showed that autistic trans people often faced extra barriers to acceptance and diagnosis.

What extra accommodations might people who are both trans and autistic need in order for us to hold space for them? What does it say about how society views trans people, and autistic people, that the identities of people who are both face extra barriers and layers of invalidation?

5.2 Trans identity and sexuality

It is a common mistake for people to confuse gender and sexuality. Although gender and sexuality do have a relationship with one another, they are not the same thing. The UK Government's National LGBT Survey (2018) tells us just 9.4% of trans respondents were straight, and 73.1% were gay/lesbian, bi, pan, or queer, while 5.4% specified asexual. And yet, trans people who are not straight after transition still face extra barriers to understanding and acceptance, and there is still confusion among some people that trans people are ‘really gay’ (as in gay and cis).

Activity 5.3: Patrick and Jake – session 12

Activity 5.3: Patrick and Jake – session 12

Here is therapist Ellis Johnson talking a little more about the difference between gender and sexuality:

Transcript

5.3 Trauma and abuse

Content note: this section talks about adult and childhood trauma and in particular sexual abuse, but not graphically.

Sadly, LGBTQA+ youth are more at risk of being targeted for abuse than other children, as are other vulnerable or marginalised young people, such as disabled or looked-after children (NSPCC 2021a; NSPCC 2021b), and this is equally true for trans people (Thoma et al., 2021). Sadly, there is an enduring narrative that abuse can cause LGBTQA+ identities (Hope, 2019; Robinson, 2016). Some ICTA participants reported a variety of health professionals perpetuating this myth, including gender clinicians. For example, one participant said:

‘The psychiatrist just bluntly asked something like, “do you think you’re trans because you were abused as a child?”. I was just looking at him like completely baffled. You’re supposed to be a doctor and you’re saying those words?’

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection

Have you ever questioned if a clients’ normative behaviour – their conformity, their heterosexuality, their cis identity, their conforming sexual behaviour, was caused or influenced by abuse? Have you seen others do this? What about the opposite? It is quite easy to notice a client’s differences and wonder what ‘caused’ them, rather than thinking ‘that’s just part of human diversity’.

Discussion

The myth about abuse causing trans identities can be internalised, and clients may come to us with questions such as ‘do you think abuse made me trans?’ Such myths can be reinforced by clinicians perpetuating them. Having helpful and trans-affirmative responses to such questions, especially if we work in survivors’ services, can put clients at their ease.

5.4 When therapists are cis

This section has focused on the diversity in the trans community but there can also be difference between client and therapist. All the way through this training we have stressed the need to examine your own assumptions and understandings in order to work ethically and effectively with trans clients. Here we revisit the question of what this kind of reflexivity might entail if you are a cis therapist working with a trans client.

Activity 5.4: Revisiting Patrick talking with Jake about transition care

Activity 5.4: Revisiting Patrick talking with Jake about transition care

Earlier you watched this clip of Patrick and Jake talking about his transition. Watch this excerpt one more time, but this time focus on how the interaction might be different if the therapist was cis.

Transcript

What are your thoughts about how/if the interaction might be different if the therapist was cis?

Discussion

The expert therapists interviewed for the ICTA project talked about how if both client and therapist are trans it is possible to explore gender and gender identity in way that may not be possible for cis counsellors. As one person said: ‘There are questions I can ask of a trans client that I don’t think a cis person could ask without that being received as a denial of that person’s gender.’ Another person said:

‘A cis friend of mine who’s a great therapist, [was] working with a non-binary client and the client wanted them to ask them lots of questions to help them explore their gender. But when she did ask those questions, it landed with the client as an interrogation because they’re so used to having to justify themselves… With a trans therapist it’s safer for the therapist to say “let’s ask all these interesting questions about your gender”. They will land with the client like interesting questions from a fellow trans person rather than interrogation through a cis gaze.’

Gender reflexivity thus potentially involves cis therapists understanding – and accepting – that they may well, for good reasons, be seen as less trustworthy, safe, competent than a trans therapist, as well as that they may not be able to support a trans client’s gender exploration in the same way that a trans therapist might.

Summary

This section has focused on working with the diversity that is represented in the trans community, and it has argued for the importance of understanding (and questioning assumptions about) co-occurrence of issues in trans people, frequency of abuse history, and that trans and cis therapists may be experienced differently by trans clients.

Here’s therapist Ellis Johnson talking about working with intersectionality:

Transcript

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection

What was the most important piece of learning that you took from this section?

Now, continue to 6 Conclusion.