Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 8 February 2026, 11:08 PM

4 Creating a safe space for trans clients

4 Creating a safe space for trans clients

In the previous sections you learned about the discrimination that trans people face and what transitioning potentially involves. This section considers how we can make the space inside the therapy/consultation room safer for trans people than the space outside.

Creating a sense of safety for clients is clearly important. Trust is recognised as a key facet of successful therapy (Allen, 2021, Fonagy and Allison, 2014) with a question on the most widely used questionnaire to assess therapeutic alliance including: ‘My therapist and I trust each other’ (Hatcher and Gillapsy, 2006). Trust helps build the therapeutic relationship, and the therapeutic relationship is one of the key drivers of therapy outcomes (Norcross and Lambert, 2019). Trust is also especially critical for any population that is marginalised as the experience of discrimination is very likely to create barriers to trust (Luchenski et al., 2018).

To begin to consider what a ‘safe therapy space’ might mean for a trans client, try the next activity.

Activity 4.1: Beliefs about trans identities

Activity 4.1: Beliefs about trans identities

The following questions are intended as a way to support you to look directly at what you think and believe. Your answers are anonymous and will not be shared. Alternatively, you can download the accessible PDF version below.

Discussion

Arguably, acceptance is the foundation of a good therapeutic relationship (Bu and Paré, 2018). However, a therapist can accept what trans people do, in a ‘live and let live’ way, whilst still denying the authenticity, the ‘realness’ of their identities. In that regard, a therapist can imagine they are holding space for trans people while still believing they know better than them. This bias against the authenticity and legitimacy of trans identity is very common, and it can be psychologically undermining for clients.

4.1 Memorandum of Understanding against conversion therapy

In 2017, all the major professional bodies overseeing psychological professions signed up to an updated version of this existing document. The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) now includes trans and asexual people, whereas previously it focused on same-sex attraction. If you belong to a professional body, you are expected not to practise conversion therapy, which is defined by BACP as follows:

‘Conversion therapy is the term for therapy that assumes certain sexual orientations or gender identities are inferior to others, and seeks to change or suppress them on that basis.’

Why is conversion therapy banned by professional bodies?

The research on conversion therapy for trans people suggests that they are even more likely than sexual minorities to have experienced conversion therapy (Higbee et al., 2020). Research also evidences the significant psychological harm conversion therapy does to trans people (Government Equalities Office, 2021; Hipp et al., 2019; Tran et al., 2024; Turban et al., 2020). This includes increasing suicidality (Turban et al., 2020; Campbell and and van der Meulen Rodgers, 2023): in general individuals who have undergone conversion therapy are twice as likely to have suicidal thoughts (Government Equalities Office, 2021; see also Blosnich et al., 2020; Meanley et al., 2020).

Additionally, conversion therapy does not ‘work’ as a government report stated: ‘There is no robust evidence to support claims that conversion therapy is effective at changing sexual orientation or gender identity’ (Equalities Office, 2021). In short, conversion therapy is proven to be both harmful and ineffective. However, that does not mean that in a prevailing culture that is doubting and undermining, it is not possible to (either deliberately or unconsciously) help a client suppress or doubt a trans identity.

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection

Does the idea that a counsellor could avoid explicitly seeking to change or suppress a client’s trans identity, but nonetheless implicitly do so, make sense to you? What impact do you think that this might have on a client?

4.2 What is affirmative practice?

Affirmative practice is the opposite of conversion therapy – where conversion therapy holds that some identities are inferior – as affirmative practice gives all LGBTQA+ identities an equal value. To offer affirmative practice, all practitioners, including those who are LGBTQA+ themselves, are likely to need to have worked on ideas and biases they have internalised from the culture around them that say that some identities are more correct or authentic, valid or valuable than others.

Affirmative practice can also be understood as the opposite of poor practice. Research studies examining trans clients’ experiences of psychological therapies suggest that they are likely to have poor/negative experiences (e.g. Compton et al., 2022; Mezzalira et al., 2025). A 2019 systematic review of this research concluded that: ‘the incompetence of MHPs [mental health professionals] appears to be a common theme across time and space, and that should not be the case’ (Snow et al., 2019, pp. 154). To understand more about what the existing literature suggests contributes to poor experience of psychological therapy for trans clients, try the next exercise, derived from the findings of Mizock and Lundquist (2016).

Activity 4.2: Common missteps in therapies with trans clients

Activity 4.2: Common missteps in therapies with trans clients

Pair the definitions with types of misstep:

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 7 items in each list.

Education burdening

Gender inflation

Gender narrowing

Gender avoidance

Gender generalising

Gender repairing

Gender pathologising

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Conducting psychotherapy as if the transgender identity of a client is a problem to be fixed

b.Relying on the client to educate the psychotherapist on transgender issues

c.Overlooking other important aspects of a transgender client’s life beyond gender

d.Stigmatising transgender identity as a mental illness to be treated or as a cause of all problems

e.Applying preconceived, restrictive notions of gender onto transgender clients

f.Making assumptions in psychotherapy that all transgender individuals are the same

g.Lacking focus on issues of gender in psychotherapy with transgender clients

- 1 = b,

- 2 = c,

- 3 = e,

- 4 = g,

- 5 = f,

- 6 = a,

- 7 = d

Trans broken arm syndrome

What ICTA participants said about their experiences of psychological therapies is discussed below, but the ‘missteps’ identified by Mizock and Lunquist are also present in the ICTA data. There were additional themes, too. ‘Trans broken arm syndrome’ is a phrase used by trans people to describe the phenomenon whereby everything is inappropriately related back to them being trans. As one participant said:

‘[If] I’ve got mental health problems, oh that’s because you’re trans. Not because of, you know, I’ve had a major bereavement or something like that. And they looked around to tie it back into transitioning or being a trans… they try too much to tie things back. And I think sometimes the mental professions have already got that fixed idea of the cause without being open to it being other things.’

When a trans person accesses therapy for something entirely unrelated, it is very important professionals do not inappropriately reference a client’s trans identity or, worse, tie something unrelated into a trans identity.

4.3 What affirmative practice looks like

In the following video, experienced trans-affirmative therapist Ellis Johnson explains some of the elements he feels are essential in an affirmative therapist:

Transcript

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection

Do you have any immediate thoughts about what Ellis says? Make a quick note in the box below.

In the rest of this section, you will be considering challenges to affirmative practice and how to work with them. First however, consider the following example of how to work affirmatively by watching this extract from Jake and Patrick’s fifth session.

Activity 4.3: Jake and Patrick – exploring without undermining

Activity 4.3: Jake and Patrick – exploring without undermining

4.4 Cissexism and transnormativity

In order to work ethically and effectively with trans clients, it is important to avoid some potential types of unconscious bias: cissexism and transnormativity.

Cissexism is the word for the way cis understandings of the world dictate how society is ordered, an ordering which is based on an un-examined assumption that only cis people exist or – sometimes – matter (Arayasirikul and Wilson, 2019). In our practices, there may be subtle and less subtle ways cissexism shows up. For example, an intake form might ask if a client is male or female and give no other option, not considering whether this question is necessary (outside of monitoring purposes, when there are good practice ways to ask it) and how complicated and jarring it might be for many trans people to answer.

Doubting or invalidating trans experiences is part of the cissexist assumption, as the following quote from one ICTA participant suggests:

‘I’m having to prove this [gender identity] to higher grade people and continually do that where the one thing that has been firm and fixed in my life has been my gender identity. I may have hidden it, I may have built a huge castle around it and pretended that it wasn’t there, and it didn’t matter. But eventually it came out and it’s consistent. Anybody who has talked to me from counsellor, from mental health services to clinicians, all of these people, it’s the same story each time.’

Transnormativity describes the existence of pre-conceptions of what a trans person is, with the consequence that trans people who do not fit these assumptions/stereotypes are seen as invalid (Riggs et al., 2019). ICTA participants reported, for example, having their trans identity being challenged because their dress, hair style or name was deemed inappropriate for their gender.

Like Patrick, trans clients may consider whether they should adapt their presentation in order to better be accepted by society. However, we as therapists might want to consider our position on this – is a person, cis or trans, only valid or acceptable if they conform to rigid ideas of how gender should be expressed and presented?

To further explore how cissexism and transnormativity might impact your attitudes to trans clients, try the following activity.

Activity 4.4: Accepting trans identities as authentic

Activity 4.4: Accepting trans identities as authentic

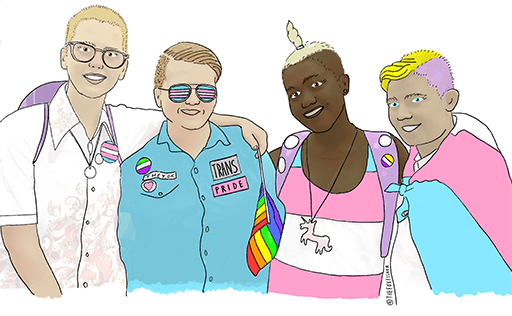

How easy or difficult is it, right now, to hold a position that the following people are as authentic, valid and valuable in their identities as anyone else? Your answers are anonymous and will not be shared with anyone.

Discussion

Hopefully, this exercise has helped you to think about any assumptions you might have about some trans identities being more valid than others.

4.5 The impact of misgendering

‘It was almost like she’d be describing what she’d say to someone about me, and it was usually in the middle of something she’s trying to say positive but then she’d call me he… And she was very apologetic and then it’d happen again. Then this last time, she was saying something about, “I’m still stuck in old ways of thinking” and I don’t know what that’s supposed to mean. I came very close to finishing it early, I felt this welling up in me and I said I found that really painful. After we ended, I thought I can’t put myself through this anymore.’

This quote comes from an ICTA participant talking about her experience of being persistently misgendered while accessing psychological therapy through a third-sector voluntary organisation. In this account, misgendering led to significant emotional distress and to termination of therapy. Given the context – a professional relationship that was supposed to support this person’s mental health – the therapist’s misgendering seems particularly damaging.

It is therefore vital that you get into the habit of checking what the correct pronouns are for all the people you work with and introducing your own pronouns. It is also essential to practise getting these right, both when you talk to the client and when you talk about the client, for example, in your notes or supervision.

To further consider the potential impact of misgendering in the context of therapy, try the next activity.

Activity 4.5: The impact of misgendering

Activity 4.5: The impact of misgendering

Watch the video of therapist Ellis Johnson talking about the impact of misgendering. While you’re watching it, reflect on what comes up for you.

Transcript

Often therapists inexperienced in working with trans people express a fear of getting it wrong as something that inhibits them. How can we resolve the tension between holding awareness that misgendering has a strong negative impact on clients with knowing too much hesitancy might disrupt the therapeutic relationship?

Discussion

ICTA participants stressed the impact on them of being misgendered, and existing literature cites the mental health burden of this repeated undermining of a trans person’s self-experience (Gunn et al., 2025; McNamarah, 2020; McLemore, 2018). When we misgender colleagues, students, clients or supervisees, it is important to reflect on this. Misgendering gives us important information about how parts of us see trans people, perhaps unconsciously. We have momentarily departed from that person’s frame of reference and from an affirmative, non-judgmental stance. If we get defensive when challenged around this, it robs us of the opportunity to work through what might be going on for us.

There is no substitute for doing ongoing work on trans acceptance and cultural competence to mitigate this harm, but it’s important to realise even experienced trans therapists make occasional mistakes, because we were all taught to look at the world in cissexist ways. What we do after making a mistake, quickly apologising and attending to the client’s feelings rather than getting caught up in our own shame response, is what counts.

4.6 Affirmative practice and therapy modalities

As a therapist you are likely to have an approach to working with clients. One question might be how affirmative practice sits alongside your modality. Our own view is that it makes sense to think of affirmative practice as a meta-theory or over-arching framework that sits beyond particular schools of therapy in terms of how they work with clients. This is similar to the notion of cultural competence as something overarching that should inform therapeutic work with clients, however we practise.

Cultural competence comprises the awareness, knowledge and skills required to work ethically and effectively with clients who differ from oneself as a therapist. The requirement to be culturally competent is a common ethical and professional standard within the psychological therapies (Soto et al., 2018). What this means is that if you (know you) are not culturally competent with respect to a particular population, you should not work therapeutically with them.

Trans-affirmative practice approaches can be considered as a specific type of cultural competence. Importantly, the research on therapist cultural competence clearly finds that therapists are not good at rating whether they are in fact culturally competent – only client-rated cultural competence is shown to be positively related to clients’ therapy outcomes (Soto et al., 2018). This underlines the importance of therapists taking on board the idea that they may not be – from their trans client’s perspective – practising affirmatively. We therefore need to be aware how our language, approaches and assumptions about the world may not be supportive to clients. It also suggests the value of giving clients space to provide feedback on how they are experiencing the therapy. To consider this more, try the next activity.

Activity 4.6: Thinking about our own modalities

Activity 4.6: Thinking about our own modalities

Davies (1996) talks about how we may need to put some of our existing training aside to practise affirmatively, if existing training models had not already addressed the biases against LGBTQA+ people that existed when the founding practitioners of our models were practising. It is important to learn to notice these biases – in the middle of the last century particularly, the profession was much preoccupied with the notion of ‘what causes this pathology’, where today we might not see pathology, only natural difference and diversity, in the case of neurodiversity or LGBTQA+ identity.

What blinkered spots does your own modality have on trans issues? What attitudes and misconceptions have you heard from fellow therapists or read in the literature?

Discussion

A paper by McBee (2013) discusses the history of pathologisation of trans identities and experiences (while also making an argument for the need for ‘a more affirming perspective’). A therapist might question the pathologising nature of the current trans healthcare process, but it is important to understand that the evidence base supports access to transition healthcare for those that want it. Affirmative practice supports the autonomy of the individual trans person to follow a path that’s right for them.

4.7 What the research tells us about affirmative practice

There is research evidence of the benefits of affirmative practice. A 2023 systematic review found that affirmative therapy was associated with reduced distress, depression, anxiety, suicidality and substance use as well as better coping and emotion regulation, self-esteem and self-acceptance (Expósito-Campos et al., 2023). A survey of trans (including non-binary) clients found that affirmative practice was associated with better therapy outcomes and client satisfaction (Pepping, Cronin and Davis, 2025) while a trans-affirmative approach, a nurturing therapeutic bond and recognition of both authentic gender and client experiences of cisnormative stigma were all associated with better therapy outcomes in another systematic review (Mezzalira et al., 2025).

Trans people will come to therapy with a range of issues that may require and respond to different approaches. Practising affirmatively is about being non-discriminatory in the way we practise our individual modalities, i.e., making sure a range of therapeutic modalities are accessible to trans clients by ensuring they are affirmative. Practising affirmative therapy is not a separate approach and it is not just for trans people – it is just as important to be trans affirmative in our stance with clients presenting as cis, because they or a loved one may at some point come out as trans, or they may have transitioned historically and not be out to us.

There is a small but growing body of literature on modality-specific trans-affirmative practice, such as:

Pachankis et al.’s (2020) evidence for affirmative, minority-stress-focused CBT interventions for anxiety and depression.

Haziza and Pehkonen’s (2025) proposal of the value of psychodynamic group psychotherapy for trans people.

Crowter’s (2022) argument for the radical value of a person-centred approach – especially unconditional positive regard – for working with trans clients.

Pachankis (2018) presents existing quantitative evidence for affirmative practice and argues for creating a further evidence base for its effectiveness. Examples of such a growing evidence base include Pachankis et al.’s (2020) evidence for affirmative, minority stress focused CBT interventions for anxiety and depression.

Austin and Craig (2015) discuss adapting CBT for trans clients with depression and anxiety, while Livingstone (2011) outlines the benefits of a phenomenological, affirmative, person-centred approach to counter experiences of pathologisation and shame.

The ICTA project suggests that further research is needed to inform and improve practice, in particular:

- Which kinds of services/approaches are a priority for developing and evidencing affirmative practices – for example, our data suggests a high need of domestic and sexual violence services, services for neurodiversity (autism, ADHD, dyslexia, etc.)

- Quantitative evidence to back up the qualitative evidence of the benefits of a non-directive, trans-affirmative approach in which clients can explore gender identity without being steered or suppressed, or fearful that expressions of uncertainty will undermine them.

4.8 How to create a safe space for trans clients

The ICTA study found very mixed experiences of psychological therapies within the NHS, third-sector organisations and in private practice. Try the activity below to find out what ICTA participants discussed as helpful for creating safe therapeutic spaces for trans people.

Activity 4.7: ICTA findings on what makes good and bad therapy

Activity 4.7: ICTA findings on what makes good and bad therapy

Sort the following statements so that they are matched with each other and in the appropriate (positive or negative) column. Alternatively, you can download the accessible PDF version below.

Summary

This section has focused on how to create a safe space for trans clients and argued that this means adopting an affirmative practice approach, avoiding behaviours and assumptions that are stigmatising or undermining of trans clients and reflecting on whether our typical approach to working with clients might need to be adapted to work with trans clients.

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection

Take a moment to consider the content of this section and the video you just watched. Are there aspects that resonate with you or that you find challenging? What can you learn about yourself from your responses to this material?

Now, continue to 5 Working with the diversity of the trans community.