Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 17 February 2026, 3:21 AM

Search and rescue of refugees at sea

1 What is search and rescue at sea?

Welcome to this course which aims to introduce you to international laws that govern maritime search and rescue (SAR). It also seeks to examine issues of wellbeing which might arise from working with traumatised people. It is designed for those who have an interest in the law of SAR at sea or may find themselves working on SAR operations.

Following this introduction, there are five main sections to study:

- Introduction to international law and the law of the sea.

- Migrants’ rights to leave their country by sea.

- Laws concerning maritime search and rescue.

- The practice of ‘pushbacks’ and how it raises human rights issues.

- Mental health risks when working with traumatised people.

Reflective and practical activities and videos are woven throughout the course to support your learning. By the end of this course, you will:

- understand international laws related to maritime search and rescue and human rights at sea

- understand potential risks to SAR workers’ wellbeing and strategies for self-care to address these.

Before moving on to the first section, take one minute to do the following activity to reflect on the starting point of your learning journey.

Activity 1: Reflection

As you begin this course, how would you describe your current level of knowledge of the international laws related to maritime search and rescue?

Discussion

You may be starting with little to no knowledge about the maritime SAR context. Or perhaps you may have some knowledge already and want a ‘refresher’. We have designed this course for those who have no or limited prior knowledge of maritime law.

2. Searching for and rescuing lives at sea – what does it mean?

Watch the following video where a volunteer discusses what it means to them to work in search and rescue (SAR).

Transcript

A SAR operation may start from a distress call at sea, or an observation of a vessel in distress, and ends when those rescued are disembarked to a safe place. The legal obligation for all vessels to conduct SAR operations is enshrined in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and further detailed in the International Conventions on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR Convention) and Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS Convention). You will learn more about these in this section and Section 4.

But what does a legal obligation mean?

A legal obligation to respond to a boat in distress means that the captain of a boat receiving a distress call, or seeing a distressed boat and its passengers, must help the people affected as quickly and safely as possible (without seriously endangering their own lives).

SAR activities can involve a number of different parties from the moment someone receives a distress call or notices a vessel in danger on the water. These include regional or national government authorities, such as border enforcement agencies and the military, private vessels, and/or civil society/non-governmental organisations (NGOs). However, certain governments as the coordinators of designated SAR regions in the world are responsible and accountable for SAR operations.

Although governments are responsible for SAR regions, the coordination and cooperation of SAR operations can depend on political agendas and motives, in particular concerning immigration and the movement of people across borders. Assisting people from drowning, attending to their basic medical needs, and bringing them to a safe place is meant to happen regardless of who they are or where they are from. Nevertheless, the political nature of immigration can impact how SAR activities are performed and, if done so negligently, can lead (and has led) to the loss of lives.

2.1 Introduction to international law and the law of the sea

Historically, the seas have been fundamental to human life, for travel, and for the resources contained within the water or in the ground beneath. The use of the oceans by people requires that we have laws which govern them. In this section, the law of the sea will be briefly introduced. The international law of the sea is one of the oldest categories of what is called ‘public international law’. In order to understand the law of the sea, it is important to first understand what public international law means.

Public international law

Public international law – commonly referred to as simply ‘international law’ – guides the relationship between states. It is distinct from private international law which regulates private relations between, for example, persons, companies, or other organisations across different legal jurisdictions.

States have, what we refer to as, ‘sovereignty’, which means that they have the capacity to make law within their jurisdiction. States are also able to enter into relations with other states. It is public international law which regulates the interactions between states. As these interactions are numerous, international law covers a wide range of different fields, of which the law of the sea is one branch, and human rights law is another (there are many more).

Public international law consists of three different sources of law. These include:

- Treaties – a treaty is an agreement between states, intended to create legal rights and duties, which is in writing and is governed by international law. Conventions are treaties, but the term ‘convention’ is used nowadays for multilateral treaties with a number of parties (rather than, for example, a treaty between two states). Treaties are created by states and binding only on those states that become party.

- Customary international law (CIL) – this is less concrete than treaties. It refers to unwritten customs existing between states that have developed over time and are now recognised as part of international law. CIL is binding on all states and is recognised through state practice and what is referred to as opinio juris: states must be shown to believe they are acting in accordance with international law. Sometimes CIL is codified into treaties.

- General principles of law – these are principles of law that can provide a source of law where there is no guidance from treaty law, or customary international law. For example, a general principle of international law is that states act in good faith in the performance of their obligations.

Public international law is different from domestic law where the law is enforced by the state. For example, in criminal law, the police, the public prosecutor, and the courts enforce the law. Society expects that those who have committed crimes are punished.

In international law, it is states who create the law, and they are considered to be equal partners in doing so. They choose to comply with the law. Their choice in complying with international law does not lead to criminal punishment in the sense known in domestic law, but it can impact on their relations with other states and, for example, lead to sanctions.

2.1.1. Freedom of the high seas and territorial waters

The matter of what states have legal control over which zones of the sea is important for SAR. This is because SAR vessels need to understand the laws of what state they may be subject to. All of the sea was once thought to be capable of being subject to jurisdiction by states, much in the same way that land is.

For example, the Portuguese in the seventeenth century proclaimed large areas of the sea as part of their territory. Hugo Grotius, the Dutch jurist and philosopher, argued in his work Mare Liberum (1609) that states should not be able to do this, and the seas should be open to use by all (‘Mare Liberum’ means ‘free sea’ or ‘freedom of the sea’). This eventually became accepted, and freedom of the high seas became a fundamental principle of international law.

However, not all seas are considered to be open. In basic terms, the sea can be split into two areas of maritime space or jurisdiction. These include those under state jurisdiction, and then there are high seas, which are beyond state jurisdiction but are where states can exercise some powers (as will be discussed in Section 2.1.2).

In 1982, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS or LOSC) was drafted. This came into force as a convention of international law in 1994 (later to be amended, but this is outside the scope of this course), and currently has 168 state parties. UNCLOS allowed for greater state control over the seas and the seabed. Through UNCLOS we can identify new categories of zones of the sea over which states have varying levels of legal control, including the contiguous zone, the continental shelf, and the more recent exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

2.1.2 The different maritime zones

In order to understand what the different maritime zones are, we need to establish first what is called the ‘baseline’. This is measured from the low-water mark (Article 5, UNCLOS) which is the level of the sea reached at low tide. The rules concerning baselines are particularly important in law because they determine whether a state has jurisdiction over certain areas of the sea. As it may be imagined, the rules regarding where baselines begin have been subject to dispute. Behind the baseline are internal waters. Beyond the baseline we can establish the following different zones.

Internal waters

Internal waters are waters ‘which lie inward of the baseline from which the territorial sea is measured’ (UN General Assembly, Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982, Article 8(1)). This includes, for example, ports and harbours, estuaries, or landward waters from the closing line of bays. States have sovereignty, or legal control, over their internal waters.

Territorial waters

Territorial waters can now be claimed up to 12 nautical miles (Article 3, UNCLOS) from the baseline. Within the territorial sea, a coastal state is sovereign and can exercise its powers on several issues, subject to some exceptions regarding, for example, the right to innocent passage. This gives the right of a ship to pass through territorial waters of a state, so long as they are not acting in a manner which is prejudicial to the peace, good order, or security of the state. States may cite a breach of the right to innocent passage and close the ports to a SAR (or any) vessel or prevent people from disembarking a vessel.

Under Article 21(1) of UNCLOS, the state may adopt laws and regulations relating to several areas. These include such areas as the safety of maritime traffic, the conservation of living resources, or importantly for SAR, under Article 21(1)(h) ‘the prevention of infringement of the customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations of the coastal State’. States may, for example, justify actions against SAR vessels to prevent disembarkation, or the closure of ports to a foreign vessel under Article 27 of UNCLOS, which relates to criminal jurisdiction of a foreign flagged vessel.

Contiguous zone

Article 33 of UNCLOS (and the earlier Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone 1958) established that the contiguous zone is a maritime area running alongside the territorial sea. The contiguous zone must be declared explicitly by the state and may extend up to 24 nautical miles from the coast.

A state has more limited powers in the contiguous zone, but again, importantly for SAR powers, these extend to ‘customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations’. In this zone, the state can act to prevent, inter alia, violations of its immigration laws, under Article 19(2)(g) and Article 33(1)(a) of UNCLOS.

Exclusive economic zones and the continental shelf

Not generally relevant to the issue of SAR, exclusive economic zones allow states to claim rights and duties to an area up to 200 nautical miles from their coastland for the purposes of exploration, exploitation, conservation, and management of living and non-living natural resources found within the zone (Article 56(a), UNCLOS).

Continental shelves refer to the landmasses that extend from continents and can be rich in resources. The coastal state has rights over exploration and exploitation of the continental shelf to its end, or to a distance of 200 nautical miles (although this may be extended).

Freedom of the high seas

Beyond the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, lie the high seas. Although the freedom of the high seas is well established, it is an urban myth that there is no law covering the high seas. All vessels must be registered under the law of a state, have an established link and fly their flag, under Article 92 of UNCLOS.

The term ‘flagged ship’ refers to a ship with a flag of a state. That state becomes known as the ‘flag state’. It is then subject to the law of that state. If there are migrants on a flagged vessel, they temporarily become ‘nationals’ of that flag state for the purposes of legal control and protection over them.

If a ship flies no flag, any state may exercise jurisdiction over it. An unflagged migrant boat when rescued by a flagged vessel will come under the protection of the flag state. They are then subject to the legal control and protection of that state (including human rights protection).

UNCLOS recognises exceptions where a state may exercise legal powers over vessels covered by another flag. These include, for example, where it is suspected a ship is engaged in piracy or slavery.

The Migrant Smuggling Protocol to the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) gives broad consent for states to board ships with flags of another state to aid in the prevention of migrant smuggling (further detail on UNTOC will be discussed in Section 4.5). There are further limitations to high seas freedom, which will not be covered here as they do not generally have relevance to SAR.

3 The rights of migrants to leave their country and when at sea

Migrants have a right to leave their countries and to travel by sea. If migrant boats are in distress at sea (as we know hundreds of vessels are each year across the world), states have a duty to rescue them under international law. This section will look at the right to leave a country, the right to seek and enjoy asylum, including the principle of non-refoulement, the duty to rescue migrant boats in distress, as well as the human rights that migrants have.

3.1 The right to leave a country, and the right to seek and enjoy asylum

The right to leave a country, including one’s own, is enshrined in most human rights conventions – meaning that there are many international sources of law which specify this right. For example, it is provided in Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966 (ICCPR):

‘2. Everyone shall be free to leave any country, including his own.

3. The above-mentioned right[s] shall not be subject to any restrictions except those which are provided by law, are necessary to protect national security, public order, public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others, and are consistent with the other rights recognized in the present Covenant.

4. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter his own country.’

A similarly worded human rights provision is provided under Article 2 of Protocol No. 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and other examples can be found across human rights law. As Article 12 of ICCPR suggests, it is a right which is qualified, meaning that states can limit or interfere with this right. They can do this ‘to protect national security, public order, public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others’.

However, any restrictions should not impair the essence of the right, they should be necessary for the purposes they seek to achieve, and they should be proportionate to their aims (Human Rights Committee, General Comment 27, Freedom of movement (Art.12), U.N. Doc CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.9 (1999)). In practice, this means that there may be some instances where states can restrict the right to free movement, but depending on the practice it may be deemed to be illegal. States restricting movement may therefore be open to legal challenge.

The right to seek and enjoy asylum is also embedded within international law. Under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) 1948, Article 14.1, ‘Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution’.

Although the UDHR is not a direct source of law, the rights of those seeking asylum were given legal standing under the UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees 1951 and its 1967 Protocol (Refugee Convention). People are recognised as refugees under the Refugee Convention if deemed to be:

‘[a] person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it’.

The protection which is provided for refugees is that they will not be sent back to the country from where they are seeking safety. This is called the principle of non-refoulement, and it is provided under Article 33 of the Convention. This applies not only to recognised refugees, but also to those who have not had their status formally declared (e.g., asylum claimants).

This has been reaffirmed by the Executive Committee of UNHCR. In its Conclusion No. 6 (XXVIII) ‘Non-refoulement’ (1977), para. (c), ‘the fundamental importance of the principle of non-refoulement … of persons who may be subjected to persecution if returned to their country of origin irrespective of whether or not they have been formally recognized as refugees’.

When people are at sea, they are also protected by human rights law. The next activity will consider applicable human rights law to people at sea.

Activity 2: What human rights instruments do you think relate to the rescue of people at sea?

Have a think about what you know (or believe you know) about human rights. What international legal instruments do you know of, and what sort of rights do they confer on people? How do you think these rights translate to the rights of people at sea?

Discussion

There are a vast number of instruments applicable to the rights of people at sea. For instance, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which forms the basis of a range of international, regional, and national human rights laws, sets out the right to life (Art 3), the right that no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Art 5), the right not to be arbitrarily arrested and detained (Art 9), and the right to seek asylum (Art 14).

The Refugee Convention, as stated above, sets out the right to non-refoulement – that is, it is an obligation on states not to send a person back to a place where their human rights are at risk (Art 33(1)).

The non-governmental organisation (NGO) Human Rights at Sea (HRAS) has developed the Geneva Declaration on Human Rights at Sea. This seeks to reaffirm the existence of various human rights instruments and rights and obligations within them and offers a useful resource to set out in clear terms the volume and coverage of human rights obligations at sea (HRAS, 2022).

4 Search and rescue at sea

Search and rescue at sea has always been carried out under customary international law.

Customary international law is distinct from the law that comes from conventions or treaties in international law. It is derived from established international practices (customs) that have developed over time.

A customary international law can be recognised by states believing they are complying with international law when acting in accordance with a custom, and consistently doing so on a widespread basis.

For centuries, ships in distress or in danger of distress have been assisted, their crew and passengers rescued, and their items salvaged where possible. The principle behind this was one of solidarity with other seafarers. In more modern times, customary international law on issues of SAR has been supplemented by international conventions and treaties.

The customary law relating to SAR was codified into Article 12 of the Geneva Convention on the High Seas 1958, which was then replicated in Article 98 of UNCLOS. This provides that ships – without seriously endangering themselves – should render assistance or seek to rescue persons at sea in danger of being lost or at distress. It also provides that states should provide for the establishment of a SAR service.

‘1. Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag, in so far as he can do so without serious danger to the ship, the crew or the passengers:

a. to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost;

b. to proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distress, if informed of their need of assistance, in so far as such action may reasonably be expected of him;

c. after a collision, to render assistance to the other ship, its crew and its passengers and, where possible, to inform the other ship of the name of his own ship, its port of registry and the nearest port at which it will call.

Every coastal State shall promote the establishment, operation and maintenance of an adequate and effective search-and-rescue service regarding safety on and over the sea and, where circumstances so require, by way of mutual regional arrangements cooperate with neighbouring States for this purpose.’

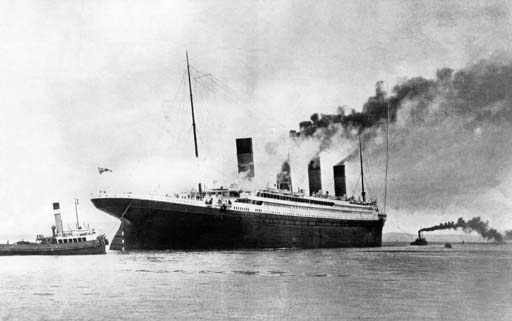

4.1 Safety of Life at Sea 1974

Following the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, and the tragic loss of life of over 1500 people, the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) was adopted. This has been recast, and the current iteration is the SOLAS Convention 1974, which came into force in 1980.

SOLAS provides the minimum safety standards for the operation of ships that are neither solely for personal nor military use. It contains various technical provisions relating to the construction of ships and the equipment that must be carried on vessels and specifies certification processes for ships. Palestine and Bosnia & Herzegovina are the only two countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea which are not signatories to SOLAS.

Chapter V of SOLAS relates to the Safety of Navigation and identifies various services which should be provided by Contracting Governments, including SAR obligations, and obligations on masters of ships to respond to distress calls.

Activity 3: SOLAS

The following is an extract of the text of Regulation 33 of the SOLAS Convention. In your own words, outline what the obligations of this Regulation mean for SAR.

‘1 The master of a ship at sea which is in a position to be able to provide assistance, on receiving information from any source that persons are in distress at sea, is bound to proceed with all speed to their assistance, if possible informing them or the search-and-rescue service that the ship is doing so. This obligation to provide assistance applies regardless of the nationality or status of such persons or the circumstances in which they are found.

1-1 . . . The Contracting Government responsible for the search-and-rescue region in which such assistance is rendered shall exercise primary responsibility for ensuring such co-ordination and co-operation occurs, so that survivors assisted are disembarked from the assisting ship and delivered to a place of safety, taking into account the particular circumstances of the case and guidelines developed by the Organization. In these cases the relevant Contracting Governments shall arrange for such disembarkation to be effected as soon as reasonably practicable.’

Discussion

It is clear that masters of ships at sea are obligated to aid persons in distress at sea speedily — and that the status of such persons is irrelevant — but governments also are obligated to coordinate the rescue to ensure survivors are quickly disembarked and taken to a place of safety. For the purposes of Chapter V Regulation 33, concerns about people smuggling and human trafficking (which will be discussed in Section 4.5) do not alter the obligations on vessels or governments.

4.2 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue

State parties to several maritime conventions need to ensure that arrangements are in place for distress communication and coordination. This is based on both Article 98(2) of UNCLOS and Chapter V of SOLAS, as well as the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR Convention). States who are party to the SAR Convention are required to ensure that measures are in place to enable the provision of adequate SAR services in their coastal waters.

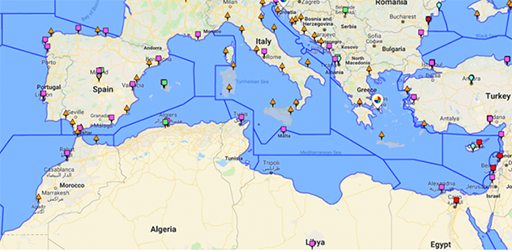

The SAR Convention sets out to provide for international cooperation for coordinating SAR operations. It specifies the establishment of SAR zones. These are independent of the maritime zones discussed in Section 2.1.2 of this course. For example, SAR zones have been established in the Mediterranean Sea, as the following picture demonstrates.

Note that a Libyan SAR zone is recognised in the above diagram. However, human rights organisations, such as Statewatch, dispute whether this zone should be allowed to be legally recognised due to recorded human rights abuses in Libya and by the Libyan Coast Guard. For more information, visit the Statewatch website.

Under the SAR Convention, a rescue is defined as ‘An operation to retrieve persons in distress, provide for their initial medical or other needs, and deliver them to a place of safety’. The state responsible for the SAR zone should designate a place of safety, but there is no rule designating that the state responsible for the SAR zone, or the flag state of the ship, should receive those persons. However, the finding of a place of safety should be applied with reference to international human rights law, and the principle of non-refoulement.

The revised International Maritime Organization (IMO) guidelines now also define a place of safety as ‘a location where rescue operations are considered to terminate. It is also a place where the survivors’ safety of life is no longer threatened and where their basic human needs (such as food, shelter, and medical needs) can be met’ (MSC Res 167(78) Annex 34: ‘Guidelines on the Treatment of Persons Rescued at Sea’ (20 May 2004) para 6.12).

4.3. Regulation (EU) No 656/2014

Where maritime surveillance operations are co-ordinated by The European Border and Coast Guard Agency, also known as Frontex, EU law applies. Regulation (EU) No 656/2014 Article 4(1) provides that ‘no person shall, in contravention of the principle of non-refoulement, be disembarked in, forced to enter, conducted to or otherwise handed over to' an unsafe country as defined in the regulation.

Where a boat is found in the contiguous zone or territorial waters, disembarkation should normally take place in the coastal Member State. If the boat is intercepted at high seas, then the preferred place of disembarkation is the state from where the vessel departed.

However, the rescued persons are required to be given the opportunity 'to express any reasons for believing that disembarkation in the proposed place would be in violation of the principle of non-refoulement'. This means that rescued persons should be allowed the opportunity to express why their return to the state they departed from could, for example, lead to a breach of their human rights, or their persecution, and would therefore be in violation of the principle of non-refoulement.

4.4. Docking at ports

SAR vessels with rescued persons onboard have encountered issues whereby they have not been allowed to dock at ports. This became particularly acute during the Covid-19 pandemic where states closed their ports or asked boats to quarantine for periods of time, stating that they were doing so to control the spread of the virus.

As stated in Section 2.1.2 of this course, states have sovereignty over their internal waters, which includes harbours, under Article 8 of UNCLOS. Article 25 of UNCLOS also confirms the right of states to regulate access to their internal waters, and this includes being able to check whether vessels comply with port entry requirements and deny ships entry which fail to comply.

Some states have sought to use the legal loophole of controlling their own internal waters to prevent disembarkation of rescued migrants. States have also argued that people are safe once they have been rescued and so their legal obligations are discharged at the point of rescue, rather than at the point of safety for passengers. However, the power that states have to prevent disembarkation at their ports is countered by the international laws regarding ensuring that those who have been rescued reach a place of safety under the SAR Convention, including relevant human rights law and the principle of non-refoulement.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) recommends that the preferred destination of a ship should be considered for disembarkation accounting for the vessel’s safety and the needs of the persons within it. Where disembarkation from the rescuing ship cannot be arranged, the government responsible for the SAR area should accept the disembarkation of the persons rescued (IMO Circular 194/2009 ‘Principles Relating to Administrative Procedures for Disembarking People Rescued at Sea’, para 3).

AS and Others v Italy

In 2021, the UN Human Rights Committee (HRC) held that Italy had failed to protect human life by delaying a rescue mission for a boat in distress in the Mediterranean Sea where more than 200 people died (a case against Malta was also made but declared inadmissible).

It was found that there was a special relationship of dependency arising from the boat having initially contacted the Italian coastguard, the close proximity of an Italian naval vessel, and legal obligations arising from the SOLAS and SAR Conventions. Within this, Italy had failed to protect life under human rights law. The HRC held that a state should take measures to respond to reasonably foreseeable threats to life within its SAR zone, or where it exercises control over people in distress.

Although not specifically addressing the issue of docking at ports, it has been argued that this decision requires states to do more to protect persons at sea and it becomes more difficult for a state to argue that its duties to rescue persons in distress are over once they have been rescued by a commercial or NGO vessel (Galani, 2021).

4.5. Duty in relation to people smuggling and human trafficking

The SAR of lives at sea is often set against the backdrop of political discourse about people smuggling and human trafficking. International measures exist, such as the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC), to underscore the need to confront such criminal activity. However, such measures need to be read and understood in relation to other obligations in international law, and do not supersede them.

With that in mind, the main focus of this section is to identify a number of relevant legal instruments which sets out obligations relating to the specific question of assisting people in distress at sea. It is set in the context of concerns that states have about people smuggling and human trafficking, as well as SAR organisations' fears that states are using such concerns as a means of preventing or criminalising their work. What this section ultimately highlights is that international legal obligations relating to sea rescue do not differentiate between categories of people who get into distress at sea.

4.5.1 Protocols supplementing UNTOC

UNTOC is an international treaty relating to the prevention of serious, transnational, organised crime. Two supplementary protocols to this Convention are particularly important to focus on in relation to people smuggling and human trafficking: the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (Protocol to Prevent Trafficking) and the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air (Protocol Against Smuggling).

The nature of people smuggling and human trafficking differ considerably. Smuggling occurs when payment is made for unlawful means of entry into a country. Trafficking relates to the movement of people across borders for the purpose of exploitation; they are unable to consent to their movement due to threat, force, and/or deception. Both protocols relating to these acts warrant their criminalisation.

Articles 5 and 6 in the Protocol to Prevent Trafficking and the Protocol Against Smuggling, respectively, identify the requirement for contracting states to adopt legislative measures to establish criminal offences of people trafficking and people smuggling for financial or material benefit. Equally, both protocols make the importance of border measures to tackle smuggling and trafficking of people very clear.

However, these articles relating to border measures offer similar text (Article 11 of both protocols). They set out the obligations of states to commit to strengthening border controls to tackle the crimes of people smuggling and human trafficking, as well as preventing commercial carriers from being used in the commission of an offence. Although, such obligations are caveated by the fact that they must be ‘without prejudice to applicable international conventions’ (Article 11(3)) and measures taken must only be ‘to the extent possible’ (Article 11(2)).

In this respect, what does that suggest about the relationship between these obligations and, for instance, the obligation to rescue as set out in SOLAS?

Overall, the obligation to rescue lives in distress at sea is absolute. Various anti-trafficking and anti-smuggling conventions exist and present obligations on states to criminalise certain conduct and develop border measures in order to tackle human trafficking and people smuggling. However, the Protocol to Prevent Trafficking and the Protocol Against Smuggling makes it clear that these obligations do not supersede the need to assist those in distress at sea.

The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights has also repeatedly, as stated by them, ‘underlined that actions against migrant smuggling must not result in punishing people who support migrants on the move for humanitarian considerations, including persons working for NGOs saving lives during search-and-rescue operations’ (europa.eu).

5 Pushbacks

There is no internationally recognised legal definition for pushbacks. In the absence of an agreed definition, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, Felipe González Morales, refers to pushbacks as:

‘various measures taken by States, sometimes involving third countries or non-State actors, which result in migrants, including asylum seekers, being summarily forced back, without an individual assessment of their human rights protection needs, to the country or territory, or to sea, whether it be territorial waters or international waters, from where they attempted to cross or crossed an international border.’

Pushbacks are widespread, existing in many migration routes. In 2019, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution expressing concerns over the practice of pushbacks, which it cited was in violation of the rights of those seeking asylum, including the right to asylum and the right to non-refoulement.

At sea, a pushback may take place by state agents by forcing a vessel to return to the territorial waters of the state that they are trying to leave. The practice of pushbacks raises several human rights issues which will be discussed in the following subsections.

5.1 The prohibition of collective expulsions

Collective expulsions refer to expelling groups of people from the territory of a state. These are prohibited under international law, for example, under Article 4 of Protocol 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). This means that individuals should have their individual cases assessed when within the territory of a state (including its territorial waters), rather than being expelled as part of a group on a boat.

In several judgments, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has condemned pushbacks, including in the case of Hirsi Jamaa and Others v Italy when the Italian coastguard intercepted a migrant boat and returned its approximately 200 passengers to Libya. The ECtHR found a breach of the prohibition on collective expulsions under Article 4 of Protocol 4 of the ECHR.

5.2 The principle of non-refoulement

As stated in Section 3.1, the principle of non-refoulement applies not only to recognised refugees, but also to those who have not had their status formally declared.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants has stated that the principle of non-refoulement should be applied to all persons, including all migrants, at all times, irrespective of their migration status. It relates to returning individuals from a state’s territory (A/HRC/47/30, para 41), and so at sea applies to territorial waters. It has been argued that the principle of non-refoulement should apply to the high seas.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants has stated that the principle of non-refoulement should be applied to prevent the return of persons in cases of serious human rights violations, such as risks to the rights to life, integrity, or freedom of the person, and of torture and ill-treatment. He has stated that states put an end to pushback practices to uphold the principle of non-refoulement (A/HRC/47/30, para 42).

5.3 Safeguarding human rights at sea

Pushbacks, when carried out violently, can lead to human rights abuse.

5.4 Bilateral agreements

Bilateral agreements exist between states concerning returning migrants. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants has also provided that ‘to return migrants to a “safe” country – not necessarily the migrant’s country of origin – on the basis of readmission agreements can risk violating the prohibition of collective expulsions or the principle of non-refoulement if such decisions do not contain an individualized assessment of each migrant’s situation’ (A/HRC/47/30, para 64).

6 Mental health risks when working with traumatised people

We now turn to the topic of how the mental health and wellbeing of search-and-rescue (SAR) workers can be affected if they observe pushbacks and other human rights violations in their work.

The nature of the work of maritime SAR can involve witnessing and working through traumatic and tragic incidents and having direct contact with traumatised individuals. It is important that SAR workers are aware of the warning signs that might suggest that their mental health or wellbeing is being affected by the work that they do.

This section discusses the impact that working with traumatised individuals, such as people seeking asylum, can have on the mental health and wellbeing of SAR workers.

This section aims to build awareness of the importance of maintaining mental health and wellbeing whilst working in the field of maritime SAR and to develop a practical strategy to prepare for, cope with and build resilience from potential emotional challenges.

Activity 4: Reflection

How would you describe your current level of awareness of mental health and wellbeing?

Supporting people who have survived dangerous crossings by sea can be physically and emotionally demanding since they may have endured previous traumatic experiences prior to the more recent stressful experience of crossing the sea.

Survivors of crossings at sea may, for example, have physical injuries, including burns from saltwater or fuel from the small boats they travelled in (Taylor, 2022). They may have sea sickness or hypothermia, or they may be in shock. They may have witnessed drownings of friends, family or other people who attempted to cross.

Activity 5: Reflection

Reflect on the potential risks to your mental health and wellbeing whilst involved in the field of maritime SAR. You may wish to consider the specific role you currently have, or have had, or are considering starting.

Answer

There are various ways in which someone's mental health and wellbeing may be affected from working with traumatised individuals in maritime SAR. Supporting people who are seeking safety from war, environmental disaster, poverty, physical harm for their political, religious or sexual identity can be emotionally draining particularly if in direct contact with them for a prolonged period of time.

There are various ways in which SAR workers’ mental health and wellbeing may be negatively affected from working with individuals who have experienced traumatic events. Two common harmful changes to workers’ wellbeing are associated with vicarious (or secondary) trauma and burnout.

6.1 What is vicarious (or secondary) trauma?

In the context of humanitarian work, vicarious trauma (also called secondary trauma) is a series of negative effects or changes in people who are exposed to other people’s suffering or distress for a prolonged period of time.

Workers in direct contact with vulnerable people can become vulnerable themselves from feeling an overwhelming sense of empathy and shared pain (Bride, 2012). In other words, they may identify with and feel their pain and suffering as if it were their own.

Watch this brief video of Dr Laurie-Anne Pearlman, a psychologist, explain what vicarious trauma is, the signs to look for in people who are affected by it and, if not addressed, how it can negatively impact their lives.

Activity 6: Vicarious trauma

In the video, what are some of the signs of vicarious trauma that Dr Pearlman talks about?

Answer

Dr Pearlman talks about how people experiencing vicarious trauma may show signs of social isolation, withdrawal and ‘spiritual disruption’. They may feel hopeless or lose their sense of purpose or meaning in their work or even their personal life.

Over time, feelings of inadequacy or inability to change the sufferer’s situation, coupled with a strong sense of responsibility for them, may set in and these are often symptoms of vicarious trauma.

Dr Pearlman mentions how people who experience vicarious trauma often start to socially isolate themselves and withdraw from situations, whether at work and/or in their personal life.

Also, she refers to a ‘spiritual disruption’ in their wellbeing. This can be described as losing a sense of connection with the wider beliefs in which we are grounded (Pearlman and McKay, 2008). She gives examples of questions that people may ask themselves:

- ‘Where is God?’

- ‘Does my work have any meaning?’

- ‘What’s the point of this whole thing?’

6.2 What is burnout?

Experiencing burnout is another potential mental health risk particularly for those in ‘helping’ roles, such as maritime SAR workers. Burnout is linked to accumulated feelings of emotional exhaustion and stress over time.

The long-term effects of burnout may be workers’ incapability to meet the emotional demands of their role, mental and physical health ailments (Zapf et al., 1999). and a decline in job/volunteer satisfaction (Lizano and Mor Barak, 2015).

It can have crucial implications for workers’ health and morale and lead to resignations (Baker, 2012). It can also lead to feelings of detachment – where workers distance themselves from those they are working with, or depersonalise them (Graffin, 2018). It can lead to feelings of hopelessness and reduced empathy (Samra, 2018).

A wider consequence of burnout in highly emotive work environments, such as in maritime SAR, is the risk of jeopardising the ability to support vulnerable people who may be in life-or-death situations.

In the next section, you learn more about what actions we can take to address burnout or vicarious trauma.

6.3 Strategies for self-care in the field of maritime SAR

By completing this course, you are already developing your knowledge and understanding of the importance of mental health and wellbeing in the field of maritime SAR. This is the first step to protecting yourself, or other humanitarian workers you work with or know, from burnout and vicarious trauma. This includes learning about ways to build personal resilience to overcome emotionally demanding times.

You may find this series of animated video clips from the Headington Institute (2020) helpful for tips in managing stress and developing resilience when facing challenging moments in your life.

Second, consider developing a self-care plan to help prepare for, cope with and build resilience from the potential emotional challenges you may encounter on the job. You may also wish to listen to more views of what self-care means to different people and why it is important to have self-care strategies.

By creating a self-care plan, you will identify resources that you can draw on if difficult situations arise. The following are some examples to get you started with creating a self-care plan (also see Table 1 in Vincett, 2018: 52–53):

- Enrol in a professional training course or self-study course on building personal resilience.

- Develop your reflective skills by writing in a journal as this can build your self-awareness and understanding of the emotions in humanitarian work.

- Limit how much time you spend reading/watching the news and on social media that may provoke angry or depressive feelings.

- Make time to regularly spend time with friends/family (outside of the field of maritime SAR).

- Exercise regularly, have a balanced diet, and limit your caffeine and alcohol intake.

- Stick to a regular sleep routine.

- Create an emotional support network and make a list of people who you could talk to if you encounter an emotionally distressing situation.

- Undertake counselling or coaching, for example, once a month, to speak to a professional who is trained to support your wellbeing.

Activity 7: Self-care plan

Begin to write a self-care plan for yourself. Consider the steps above. Identify who you could include in your emotional support network. Keep your plan somewhere where you can refer to it easily, adjust accordingly and continue developing it over time.

Discussion

Some suggestions for a self-care plan may be:

- Do an online search for resources about resilience and read more about it.

- Spend time, at least once a month, with friends who are not activists or in the area of supporting refugees and asylum seekers.

- Practice mindfulness, meditation and yoga once a week.

- Watch comedies and light-hearted films/shows or read books of a similar genre. Avoid tense, dark or politically controversial subjects.

- Notice what type of events or occurrences during SAR activities bring about intense negative feelings in you. (These are what you may be more sensitive to and could trigger stress. Therefore, your self-care plan will be useful during these times.)

- For those currently in SAR roles: If on a rescue mission for a lengthy period of time, make time at some point each day to mentally ‘switch off’ and not think about the day’s activities.

7 Summary

This course sought to introduce you to international laws regarding search and rescue (SAR), highlighting the obligations that vessels and states have in ensuring that people are rescued when they are in danger or distress, regardless of their status.

It outlined rights that migrants have to leave their countries and their rights not to be returned to them if they might be subjected to human rights abuse, without due consideration to ensuring that the individual merits of their cases are examined.

It also examined issues relating to the mental health and wellbeing of those who save lives at sea and strategies for self-care to address these.

This short course can only touch upon some of the fundamental areas of law that govern the sea. There are other areas which the law touches upon, such as the regulation of the safety of vessels, which were outside the scope of this course but are still important for maritime SAR work.

Nevertheless, the course team hope that it has been a useful introduction and we invite you to attempt the multiple-choice, end-of-course quiz where, upon passing, you will receive a digital badge.

End-of-course quiz

This short quiz is a great way to check your understanding of the course content with questions based on the learning material you have just reviewed. To pass this end-of-course quiz, you must achieve a minimum score of 80%, and then you will be awarded a digital badge.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Neil Graffin (The Open University Law School), Joanne Vincett (Liverpool John Moores University) and Matt Howard (University of Kent, Kent Law School).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Course/banner image: Andrew Aitchison

Figure 1: Fabian Heinz / sea-eye.org

Figure 2: Georgios Kollidas / 123rf

Figure 3: Christian Ferrer / Wikimedia Commons, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

Figure 4: Refugee Rescue

Figure 5: Alan Kurdi / sea-eye

Figure 6: Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Figure 7: Search and Rescue contacts / managed by the Canadian Coast Guard at MRSC St. Johns.

Figure 8: Refugee Rescue

Figure 9: Fabian Heinz / sea-eye

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.