Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 March 2026, 10:59 AM

1 Introduction to Parkinson’s

1.1 Introduction

Health and social care professionals from various professions will be taking this course. We will therefore use the word ‘client’ to refer to a person with Parkinson’s that you work with. You may usually use ‘patient’, ‘resident’ or another term.

How to study the course

In this course, you will work online at a pace that suits you. You can study it on your own and in your own time. However, if you are in a workplace, you can also use the course as an opportunity to connect with your peers and as a framework to support group work with colleagues.

Our approach

We take a person-centred approach to care. Person-centred care means focusing on someone’s needs as an individual and recognising that their life is not defined by Parkinson’s.

People with Parkinson’s and their carers (if they have one) are experts in their own condition and should be consulted on what they think their needs are. Anyone involved in the care of a person with Parkinson’s should help them to focus on what they can do, not what they can’t do.

In this section we look at the following questions:

- Why are we here?

- What is parkinsonism?

- What is Parkinson’s?

- What causes Parkinson’s?

- How many people have Parkinson’s?

- How old are people when they get Parkinson’s?

- How is Parkinson’s diagnosed?

- How does Parkinson’s progress?

As you work through the course, think about not only your role but also that of other professionals.

Transcript

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

Learning outcomes

The purpose of this section is to give you an understanding of the common symptoms of Parkinson’s and how the condition progresses.

By the end of this section you should be able to identify and describe the following:

- the range of common conditions in which symptoms of parkinsonism may be experienced

- what Parkinson’s is and what causes the condition to develop

- the key motor symptoms and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s

- the average age of onset of Parkinson’s

- the typical stages of the progression of Parkinson’s.

1.2 Why are we here?

Before we start, let’s think about reasons for studying this course about Parkinson’s. You might have decided to take this course because you are working to support a number of people with Parkinson’s. Maybe you also have a personal interest in this condition, or you feel you could do a much better job if you understood the condition. Maybe your manager told you to take this course. Or perhaps you have management responsibilities or want to use the materials yourself. As much as possible we have designed the course to support those different contexts.

Remember there are no wrong answers here.

We have created a reflection log for you to record your thoughts when answering questions throughout the course. Use your reflection log to answer the following questions:

- Why did I decide to take part in this course?

- What experience of working with people with Parkinson’s do I have?

- How do I feel about this experience? (For example, have you found the work satisfying or straightforward? Or perhaps you found it quite challenging?)

1.3 What is parkinsonism?

‘Parkinsonism’ is an umbrella term used to cover a range of conditions. These conditions share the symptoms of slowness of movement, stiffness and tremor.

Most people with a form of parkinsonism have idiopathic Parkinson’s, also known as Parkinson’s, which this course focuses on. However, other types of parkinsonism are described below.

Multiple system atrophy

Both multiple system atrophy (MSA) and Parkinson’s can cause stiffness and slowness of movement in the early stages. But the additional problems that develop in MSA, such as difficulty with swallowing, incontinence and dizziness, are unusual in early Parkinson’s.

Progressive supranuclear palsy

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a very rare condition characterised by a problem with a person’s eye gaze, sometimes referred to as ‘doll’s eyes’. A person with PSP has to move their head to follow a finger rather than just moving their eyes, will have difficulties looking down, may also experience frequent episodes of falling backwards and have issues with mobility, speech and swallowing. Problems with speech are unusual in early Parkinson’s. PSP is sometimes called Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome.

Corticobasal degeneration

This condition is similar to PSP and very rare. People with corticobasal degeneration may experience sudden difficulty in controlling one of their limbs – usually their hand or arm, but sometimes their leg can be affected. They may experience muscle stiffness, rigidity and spasms in the affected limb.

The three conditions mentioned above progress more quickly than Parkinson’s, are harder to treat and may not respond to medication as effectively.

Vascular parkinsonism Parkinson’s

People may experience this form of parkinsonism (also known as arteriosclerotic parkinsonism) if they have had a stroke. Often the stroke can be so mild that they didn’t notice it. The most common symptom of vascular parkinsonism can be difficulty with walking – the condition is sometimes called lower body parkinsonism. Other symptoms include rigid facial muscles (hypomimia), difficulty with swallowing or speaking, and bladder and bowel problems. People with this condition may not respond as well to Parkinson’s medication as those with idiopathic Parkinson’s.

Drug-induced parkinsonism

Drugs that block the action of dopamine in the brain can result in people developing symptoms of drug-induced parkinsonism. These drugs include ‘antipsychotics’ or ‘neuroleptics’, which are sometimes used to treat dementia, symptoms associated with learning difficulties or severe mental health problems, such as schizophrenia.

This condition tends to remain static and does not progress. The only way to relieve the symptoms is for the person to stop taking the drug that is causing the symptoms of drug-induced parkinsonism. If this is possible, some people will recover within a few months.

Unfortunately, this is not always possible, as some people may have few other drug options available to manage their condition. Parkinson’s medications are contraindicated when taking these drugs, so the person has to live with the symptoms.

Have you come across this before or do you now recognise something you did not understand in a person you have been caring for?

Essential tremor

This is the most common type of tremor. It is a trembling of the hands, head, legs, body and/or voice. It is most noticeable when a person is moving and stops when someone is resting.

An essential tremor can be difficult to tell apart from a Parkinson’s tremor.

In Parkinson’s, a resting tremor usually goes away when a person is doing something like picking up and drinking their cup of tea. It will be most obvious when they are resting, such as watching television.

For people diagnosed with a benign tremor condition, multiple system atrophy or progressive supranuclear palsy, the following organisations can offer more specific support, including advice for professionals.

The National Tremor Foundation

01708 386399

The Multiple System Atrophy Trust

0333 323 4591

support@msatrust.org.uk

The PSP Association

0300 0110 122

helpline@pspassociation.org.uk

1.4 What is Parkinson’s?

We have looked at the different conditions that come under the umbrella term ‘parkinsonism’. The rest of this course focuses on the condition that affects most people – Parkinson’s.

Imagine what your life would be like if your brain wanted to send your body a message, but it couldn’t get through. Or if you wanted to speak, but you couldn’t get the words out. Or if you wanted to walk, but your legs were fixed to the spot.

It’s neurological

Parkinson’s is neurological. People get it because some of the nerve cells in their brains that produce a chemical called dopamine have died. This lack of dopamine means that people can have great difficulty controlling their movement.

The three main motor symptoms of Parkinson’s are tremor (a resting tremor and an action tremor), rigidity (stiffness) and slowness of movement. These are called motor symptoms.

But the condition doesn’t only affect mobility. People living with the condition can also experience non-motor symptoms, including fatigue, pain, memory problems, depression, constipation and many others. Non-motor symptoms can have a huge impact on the day-to-day lives of people with the condition.

It’s progressive

Parkinson’s gets worse over time and it can be difficult to predict how quickly the condition will progress. For most people, it can take years for the condition to get to a point where it can cause major problems. For others, Parkinson’s may progress more quickly.

Treatment and medication can help to manage the symptoms, but may become less effective in the later stages of the condition. There is currently no cure.

Generally, Parkinson’s is considered to have four stages: diagnosis, maintenance, advanced (often called the ‘complex phase’) and palliative. We will look at the different stages of Parkinson’s towards the end of this section.

It can fluctuate

Not everyone with Parkinson’s experiences the same combination of symptoms – they can vary from person to person and progress at a different speed. This means that no two people will follow exactly the same treatment routine.

Also, how Parkinson’s affects someone can change from day to day, and even from hour to hour – symptoms that may be noticeable one day may not be a problem the next. This can cause frustration for both the person with Parkinson’s and their carer or family.

Because of the fluctuating nature of Parkinson’s, it is vital that care needs are not assessed in just one visit. We will look at the fluctuating nature of Parkinson’s in more detail in Section 2.

Think about what you have learnt so far. How might you feel if you had to live with Parkinson’s?

Use your reflection log to write down in 150–200 words how you might feel if you were unable to control your movement. There are no right or wrong answers – just be honest.

1.5 What causes Parkinson’s?

Currently scientists don’t know exactly why people get Parkinson’s, but research suggests that it’s a combination of genetic and environmental factors that cause dopamine-producing nerve cells to die.

Most people with parkinsonism have idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, also known as Parkinson’s. ‘Idiopathic’ means that there is no known cause.

Genetic factors

It is rare to find more than one person in a family with Parkinson’s. Parkinson's can be hereditary, but it is very rare for it to run in families.

In fact, even if a person has a genetic susceptibility to Parkinson’s, it is not guaranteed that they will eventually develop the condition. Scientists believe that the condition is only triggered following exposure to other factors.

Environmental factors

There is some evidence that environmental factors (such as toxins) may trigger dopamine-producing nerve cells to die, leading to the development of Parkinson’s. Several toxins have been shown to cause symptoms similar to Parkinson’s. There has been a great deal of speculation about the link between the use of herbicides and pesticides and the development of Parkinson's.

Dopamine

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter or chemical messenger. It transmits messages between our brain and our muscles to help us perform movements like standing up or sitting down and sequences of movements like getting out of bed and going downstairs. These actions are all made up of lots of movement sequences – we just don’t tend to think of them like that.

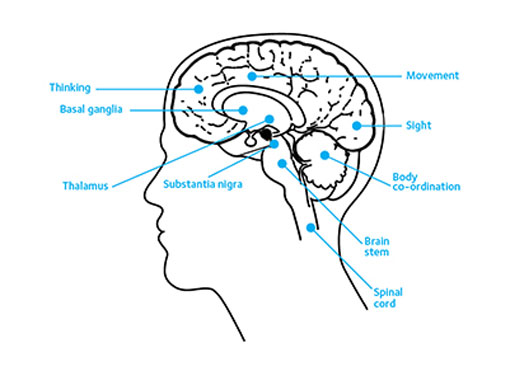

Dopamine is produced and stored in a small part of the brain called the substantia nigra. This is located within the basal ganglia, deep in the lower region of the brain, on either side of the brain stem.

Figure 1.1 shows the substantia nigra – the small part of the brain where dopamine is produced and stored.

Motor skills require learned sequences of movements that combine to produce a smooth, efficient action for a particular task. It is the role of the basal ganglia to coordinate and control these learnt, voluntary and semi-automatic motor skills. The body uses dopamine as a signal between the brain and the muscles to help these movement sequences happen.

That’s why a lack of dopamine means that people can have a great deal of difficulty controlling their movements.

Dopamine also contributes to thinking and memory (cognitive processes), such as maintaining and switching focus of attention, motivation, mood, problem solving, decision making and visuospatial perception (our ability to process and interpret visual information about where objects are). These are some of the reasons why Parkinson’s can cause symptoms such as depression or anxiety. It is also why it can be difficult for people with Parkinson’s to move through a crowded room without bumping into other people or objects.

People show symptoms of Parkinson’s when about 50% of their dopamine-producing nerve cells have been lost.

The animation below shows the difference between what the middle section of the brain of someone without Parkinson’s looks like with dopamine still present and what the same section of the brain would like in someone with the condition.

(The animation is also available as a PDF file.)

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

1.6 How many people have Parkinson’s?

Parkinson’s is becoming increasingly common. There are currently around 145,000 people in the UK living with a Parkinson’s diagnosis.

With population growth and ageing, this is likely to increase by a fifth to around 172,000 people in the UK by 2030.

1.7 How old are people when they get Parkinson’s?

The risk of developing Parkinson’s increases with age. Most people get Parkinson’s aged 50 or over , and men are more often affected than women. However, in some cases, Parkinson’s is diagnosed before the age of 50 – this is known as young onset Parkinson’s.

If Parkinson’s is diagnosed before the age of 21, it is known as juvenile Parkinson’s, although this is rare.

These statistics emphasise the importance of considering what stage a person with Parkinson’s is at, rather than their age when you’re assessing their care needs. For example, you may find that you’re caring for a very elderly person and a much younger person who are at the same stage in their condition.

1.8 How is Parkinson’s diagnosed?

Confirming that someone has Parkinson’s can take time – sometimes years. This is because, as we saw earlier in this course, there are other conditions, such as multiple system atrophy (MSA), with similar symptoms. There is also no definitive test for diagnosing Parkinson’s.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guideline for Parkinson’s disease in adults (NG71) is the recommendation of best practice for doctors in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Previously in Scotland, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Parkinson’s guidelines applied. However, these are now out of date and have been archived, so no longer apply.

The NICE guideline recommends that if a GP suspects that a patient has Parkinson’s, they should be referred to a specialist in movement disorders quickly and untreated. This can be a neurologist or elderly care physician.

To confirm a diagnosis, the consultant will carry out a detailed neurological history and clinical examination. They will be looking for specific motor symptoms, such as:

- Resting tremor: About 70% of people with Parkinson’s will have a resting tremor. This is a tremor that occurs when the muscle is relaxed. Tremor will usually begin on one side of the body and then progress to both sides as the condition itself progresses.

- Slowness of movement (bradykinesia): People with Parkinson’s may find that starting a movement and performing everyday tasks can be difficult. The size of movement is often reduced and the coordination or sequencing of movements also becomes more difficult.

- Rigidity: This is when muscles become stiff or inflexible, and it can make it difficult to do everyday things and can be very painful. Some people have problems turning around, getting out of a chair or making fine finger movements, such as fastening buttons or touch-typing. Some people may not be able to swing their arms very well. Others find that their posture becomes stooped or their face becomes stiff, so it’s harder to make facial expressions.

We will look at these key motor symptoms in more detail in Section 2.

To make a diagnosis, a specialist will usually follow the criteria developed by the Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank. A diagnosis of Parkinson’s is given when any two of the three classic symptoms of Parkinson’s are present. These are tremor, slowness of movement and rigidity. Ideally people should be seen by the specialist or Parkinson’s nurse every 6–12 months after they have been diagnosed. This makes sure a person’s condition can be monitored and their medication regime can be reviewed.

Because the symptoms of idiopathic Parkinson’s may be similar to other forms of parkinsonism, people can sometimes be misdiagnosed. This is another reason why it is important that a person’s condition is reviewed regularly by a specialist.

Find out more about how Parkinson's is diagnosed on our website, where you can also download an information sheet.

Further information and links to the NICE guideline can be found on the Parkinson’s UK website.

For more about Neurological Health Services Clinical Standards by visiting the Healthcare Improvement Scotland website.

Use your reflection log to write down in about 150–200 words how what you are learning relates to people you are caring for or have cared for.

1.9 How does Parkinson’s progress?

Parkinson’s is often described as having four stages (also referred to as ‘phases’): diagnosis, maintenance, advanced (often called the ‘complex phase’) and palliative.

The progression of Parkinson’s is not always a straightforward process. Sometimes, if a person’s medication is reviewed and they begin to receive more appropriate treatment, it is possible for their condition to revert from the advanced to the maintenance stage.

Look at the animation below, which lists the stages of Parkinson’s. This shows the average number of people in a particular stage at any one time, the average length of each stage and examples of the care required at each stage. Remember that these numbers are averages and so not everyone will spend the same length of time in any one of the stages.

The animation suggests a linear path through a series of stages. In real life, people are unlikely to progress through each stage one after the other – particularly around the maintenance and advanced stages, where the effectiveness of medication can alter people’s experiences.

(The animation is also available as a PDF file or online.)

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

Diagnosis

This stage refers to the point when the person receives their diagnosis. The information and support a person receives at this time is very important. A person diagnosed with Parkinson’s should be provided with all the information they need to help them to adjust to life with the condition. Parkinson’s UK offers a range of support to people with Parkinson's, at all stages of the condition. This includes answering questions through their helpline or providing health information on the condition.

Being diagnosed with Parkinson’s can be an emotional experience and everyone will react to the news in their own way. Not everyone will want a lot of information or detail about Parkinson’s straight away. But it is very important that they know where to access more information and support when they are ready for it.

You can help people with Parkinson’s by signposting them to Parkinson’s UK.

Think about your own experiences either personal or professional. How might you feel at this point?

The appropriate process for diagnosis is discussed in Section 1.8. The NICE guideline recommends that if a GP suspects that a person has Parkinson’s, they should be referred untreated to a specialist in movement disorders before any treatment is considered. This can be a neurologist or elderly care physician.

Not everyone will immediately be prescribed medication at the point of diagnosis. If symptoms are mild, some people, together with their specialist, may decide to postpone drug treatment until their symptoms increase.

Further information and links to the NICE guideline can be found on the Parkinson’s UK website.

Maintenance

By this stage, a person’s symptoms will have increased significantly. Most people will be on a medication regime to control their symptoms. A person’s condition and medication regime should be reviewed every six months to make sure that they have the best quality of life possible.

Advanced (complex phase)

In this course, we will focus on advanced Parkinson’s as this is the point when you are most likely to come into contact with a person with Parkinson’s in your workplace. Although there is no specific definition of what advanced Parkinson’s is, it usually refers to when Parkinson’s symptoms begin to significantly affect a person’s everyday life. It is not to do with a person’s age or how long they have had the condition.

It may also be a time when Parkinson’s drugs are less effective at managing a person’s symptoms, or side effects are outweighing benefits. A person may also have a more complex drug regime which may need to be altered frequently to meet the changing nature of the condition.

At this stage, people will be likely to have less independence and need help with activities of daily living. This is because the condition is less controlled as treatment becomes less effective. It is likely that many people with Parkinson’s will feel they have to give up a number of hobbies or leisure activities that they have previously enjoyed. However, evidence shows that exercise and keeping moving is important at all stages of the condition and helps with day-to-day activities when symptoms are advanced. This could be as simple as chair-based exercises, muscle stretches or mental effort too. The Parkinson’s exercise framework has more information on this which you can use to encourage people with Parkinson’s to stay as active as they can.

Although the condition progresses differently and at a different speed for each person, the advanced stage can potentially cover a long period of time.

Someone with advanced Parkinson’s may experience the following:

- drug treatments that are no longer effective

- a complex drug regime

- more ‘off’ periods (times before the next dose of medication when symptoms are not well controlled) and dyskinesia

- increased mobility problems and falls

- problems with swallowing

- mental health symptoms such as depression, anxiety, hallucinations and delusions, and dementia

- reduced independence

- less control of Parkinson’s symptoms, which become less predictable.

Some people experience pain as a main symptom of Parkinson’s and this becomes more likely in the advanced stages of the condition. So at this stage, management of pain is crucial.

Because of the range of symptoms and the increase in their care needs, it is important that people with Parkinson’s have access to a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals. This will include their specialist, Parkinson’s nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech and language therapist, continence nurse and dietitian.

A person with Parkinson’s may also need access to other services, such as counselling, social services, falls services, respite care and day care at home.

As a health or social care professional, you are a key part of this team. You may have people with Parkinson’s referred to you, or your role may be to monitor the condition on a regular basis and raise any issues with your manager, who can alert the relevant healthcare professional.

Different members of the multidisciplinary team should also be able to advise you on any relevant care points. These may include swallowing techniques, posture and different diet options if someone has problems eating; equipment that may help with mobility; and strategies to help someone who is experiencing hallucinations, delusions or anxiety.

Drawing on your own experiences, either from your professional observations or personal life, write 200 words in your reflection log to describe the possible physical, emotional and social impacts of this stages on a person’s life.

Palliative (end of life)

In the palliative stage, the major challenge is to achieve the best quality of life and maintain a person’s dignity. Appropriate pain control and support services should be in place.

A person in this stage of their condition may need regular reviews of their medication. Many people may need to stop taking some medications because of an increased sensitivity to side effects or because they are not working as well as they used to. Some people may also be unable to take medication orally.

A local Parkinson’s nurse or the person’s specialist can provide advice about how this period should be appropriately managed.

Although the condition progresses differently and at a different speed for each person, the palliative stage can potentially cover a long period of time. Some of the more advanced symptoms can lead to increased disability and poor health. This can make someone more vulnerable to infection. People with Parkinson’s most often die because of an infection or another condition.

The care plan of someone with Parkinson’s should include details of their wishes for end of life. This will include who they want to be with them, any spiritual or religious needs, and where they want to be when they are dying. This may or may not be where they currently live.

For more information around delivering services, care and support at the palliative stage, please read the NICE guideline (NG142) End of life care for adults: service delivery, as well as looking at the Quality standard (QS13) End of life care for adults.

Care plan action

It is important that you find out whether your resident or client has a care plan in place regarding their preferences for how the issues surrounding advanced Parkinson’s should be managed. This should include legal documentation, such as a Power of Attorney and an advance decision (also known as an Advanced Directive or Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment and Living Will). This care plan should also include information about palliative care and the person’s wishes for end of life.

The NICE guideline for Parkinson’s disease in adults recommends that opportunities to discuss information on prognosis of Parkinson’s should be made available early on and should focus on shared decisions with the patient and their family. You should also consider that the person with Parkinson’s will need different information from their family member or carer.

If a person does not have a care plan in place, you should help them to develop one. This should be in discussion with the person, their carer and family members (if relevant).

We have information that gives people with Parkinson’s more detail about preparing for the practical and emotional aspects of death and dying.

Read more in our booklet on preparing for end of life.

1.10 Summary

We have now looked in detail at what parkinsonism is, what Parkinson’s is and what causes it, how many people have Parkinson’s, and the average age at which they are diagnosed. We have also looked at how Parkinson’s is diagnosed and how it progresses. Hopefully you have considered how this information can help you improve your practice and increase, where appropriate, the involvement of other health and social care professionals.

The following exercises will help you consider the impact of living with Parkinson’s. They will test what you have learnt and give you the opportunity to research services in your local area.

Exercise 1.1

We will now look at an exercise that focuses on a case study. You can record your thoughts in your reflection log.

Think back to the information in Section 1 about people who are diagnosed at a relatively young age. Remember, it is vital to focus on the stages of Parkinson’s and not the age of the person you are caring for when considering their care needs.

Case studies are common with health and social care professionals and are a way for you to explore your learning through looking at real lives. This is the first of a series of case studies that you will encounter on this learning journey. The exercises will help you develop your understanding and refine your knowledge. They can act as a useful practice for the exercises at the end if you choose to submit material to gain credit.

Please think about the emotional, social and psychological impact of Parkinson’s on the case study subject and their family. Also, think about how they feel about the progression of the condition. Use your reflection log to record your thoughts.

Case Study 1.1 Daxa’s story

Daxa is 55 and lives in Leicester. She was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2019. Here she shares her story.

My journey began in 2016. At the time I had a stressful role in child protection and prevention work. Initially I noticed a small tremor in my right hand. Then I began having falls, one of which led to me needing surgery on my shoulder.

Although I saw a neurologist about my problems, she thought I had anxiety and that was causing my tremor. I was sure there was more to it, and started keeping a diary of all my symptoms. Soon the tremor became more noticeable – it felt like all the muscles in my hand and foot were contracting and my fingers were getting stiff and sticking together.

I’d find myself freezing like a statue and my family saw how slowly and stiffly I was moving. By this point I had a long list of symptoms, and I had a strong feeling that it might be Parkinson’s, so I decided to get a referral to another neurologist. The neurologist disagreed, and said I was suffering from stress-related tremors. He suggested that my other problems were probably because of the menopause.

Looking back now, I know at that point I should have pushed back and insisted on more tests. At the time, though, I felt like my symptoms were still manageable and I had a big round-the-world cruise trip planned. So I waited.

The adventure of a lifetime?

In January 2019 I embarked on a 4-month cruise trip across the globe with my cousin. Just 2 weeks into the trip my symptoms started getting worse – I had excruciating muscle pain in my right arm and leg, chronic fatigue, and cramping in my toes. I took painkillers and tried some alternative therapies to try and alleviate my symptoms.

I had to take life on the cruise ship one day at a time and tried to cope as best I could. Normally I’m an active and fun-loving person, but my pain and discomfort meant I couldn’t stay focused, and I struggled to sit or stand for long without becoming fatigued. It was also hard not being able to fully enjoy all the activities and excursions on board.

When I returned home, I was determined to finally get confirmation of what was causing my symptoms.

Getting answers

I started seeing my GP regularly. We tried lots of different medications, including hormone replacement therapy to see if my symptoms were linked to the menopause. But 3 months later, I was still suffering and the me

Eventually my GP agreed to make another referral to a neurologist, but there was a significant waiting list.

At my dad’s 80th birthday party a couple of months later, my family were shocked to see the deterioration in my health. I was becoming increasingly disabled, and my symptoms were impacting my day-to-day life. As a family, we decided I should see a private neurologist as soon as possible.

At my very first appointment the neurologist told me that he suspected I had Parkinson’s. He started me on Parkinson’s medication and immediately scheduled me for a DaTSCAN. After just a few weeks, I could feel my symptoms improving and I really wanted to get the results of my scan to finally get a confirmed diagnosis.

When my neurologist told me I had Parkinson’s, he was very reassuring and helped to ease my anxieties. I was lucky I was able to see a private neurologist so quickly. I felt listened to and valued as a person, and I was so grateful that I had gone with my gut instinct and found someone who really took what I was saying on board.

Adapting to life with Parkinson's

I often remind myself that my future is in my hands – I’m in control of my own life.

My medication is helping, although some of the side-effects like feeling dizzy, drowsy and nauseous are hard to cope with. I’ve been trying out different alternative therapies too, including reiki, meditation, yoga and herbal treatments. Making other positive changes in my life is helping – I’m eating more healthily and pushing myself to walk as much as possible.

I have plans to start dancing, travelling, and volunteering again. My Parkinson’s might make this challenging, especially as it’s so different every day, but I’m determined to try.

What I’d really like is to be a positive role model for other people going through their own journey to diagnosis. In the Indian community in particular, there is a lot of reluctance to talk about disabilities – I’d love to help change people’s attitudes and inspire more people to share their stories.

Everyone’s life is different, and this is mine. Getting a diagnosis wasn’t easy, but I’m learning more every day and gradually adapting to life with Parkinson’s.

My Parkinson’s journey continues.

Now try the Section 1 quiz.

This is the first of four section quizzes. You will need to try all the questions and complete the quiz if you wish to gain a digital badge. Working through the quiz is a valuable way of reinforcing what you’ve learned in this section. As you try the questions you will probably want to look back and review parts of the text and the activities that you’ve undertaken and recorded in your reflection log.

Personal reflection

At the end of each section you should take time to reflect on the learning you have just completed and what that means for your practice. The following questions may help your reflection process.

Remember this is your view of your learning, not a test. No one else will look at what you have written. You can write as much or as little as you want, but it will be helpful for you to look at your notes when preparing for your assessment.

Use your reflection log to answer the following questions:

- What did I find helpful about the section? Why?

- What did I find unhelpful or difficult? Why?

- What are the three main learning points for me from Section 1?

- How will these help me in my practice?

- What changes will I make to my practice from my learning in Section 1?

- What further reading or research do I want to do before the next section?

Exercise 1.2

Using the template supplied, create a community map of support contacts in your area for a person with Parkinson’s. It may include contacts with local statutory or voluntary services, informal contacts within your community, and anything else you think shows a picture of your local area.

You might find it useful to speak with other colleagues, use the internet or visit your local community centre. In the centre of the template is the person with Parkinson’s. Write in as many different support contacts as you can find in the circle below.

If you are part of a study group, this is an activity that you could undertake together.

Now that you’ve completed this section of the course, please move on to Section 2.

Glossary

- basal ganglia

- The part of the brain that controls movement. It is made up of different parts, including the substantia nigra, which produces dopamine.

- bradykinesia

- Slow movements – one of the three main symptoms of Parkinson’s.

- cognitive processes

- Mental processes involving thinking and memory.

- delusions

- When a person has thoughts and beliefs that aren’t based on reality.

- dopamine

- A neurotransmitter or chemical messenger. This chemical transmits messages between the brain and muscles that help people to perform sequences of movements. Dopamine also contributes to some thinking and memory processes.

- hallucinations

- When a person sees, hears, feels, smells or even tastes something that doesn’t exist.

- hypomimia

- The loss of facial expression caused by difficulty controlling facial muscles.

- idiopathic Parkinson’s

- When a person’s Parkinson’s has no specific known cause.

- motor symptoms

- Symptoms that interrupt the ability to complete learned sequences of movements.

- multidisciplinary team

- A group of healthcare professionals with different areas of expertise who can unite and treat complex medical conditions. Essential for people with Parkinson’s.

- neurological

- Involving the nervous system (including the brain, spinal cord, the peripheral nerves, and muscles).

- non-motor symptoms

- Symptoms associated with Parkinson’s that aren’t associated with movement difficulties.

- parkinsonism

- An umbrella term that describes conditions which share some of the symptoms of Parkinson’s (slowness of movement, stiffness and tremor).