Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 22 November 2025, 3:01 PM

3: ‘Care’ and ‘Childhood’

3: ‘Care’ and ‘Childhood’

This training program focuses on the care of children and young people, and more specifically, Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC). When it comes to thinking about ‘care’, the CCoM project argues that it is also important to think about ‘childhood’. These concepts are highly related to each other and help us reflect on our assumptions about the children and young people we work with. First, it might be a useful exercise to think about what childhood means to you.

Activity 3.1: Thinking about ‘childhood’

Activity 3.1: Thinking about ‘childhood’

Take a couple of minutes to think about what ‘childhood’ means to you. What words spring to mind?

Make some notes in the box below.

Discussion

Some words you might have thought of are: ‘innocence’, ‘play’, ‘school’, ‘friends’, ‘fun’ or ‘protected’.

Activity 3.2: Changing childhoods across time

Activity 3.2: Changing childhoods across time

Society’s views about how children should be treated, governed and talked about have changed considerably over the centuries (Cox, 2002). Ariès (1962), a history scholar, studied the way children were represented over time through paintings, poems and iconography. Take a look at some paintings and photos of children from different times and circumstances.

- What do you notice about the way the children are depicted?

- What do these illustrations tell you about their lives?

- What can they tell you about how childhoods have changed over time?

Make some notes in the box below.

Figure 3.1a (left) and 3.1b (right): Portraits of children. Left: Portrait of a child by Cornelis de Vos (1584−1651), hanging in Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, England. Right: Portrait of the Infanta Margarita, aged five, 1656, by Diego Velázquez.

Discussion

You may have noticed how children of wealthy families, such as those depicted in Figure 3.1, were once dressed like ‘miniature adults’. Ariès argues that ‘childhood’, as separate from adulthood, only emerged at the end of the Middle Ages in Europe. Even so, children in poorer circumstances entered into the world of work at an early age, a practice that still occurs in many countries around the world.

Within social work practice, it was the Children Act 1989 which was the defining piece of legislation which recognised the centrality of children's rights (as separate to their parents). This is still the key piece of legislation for children's social work.

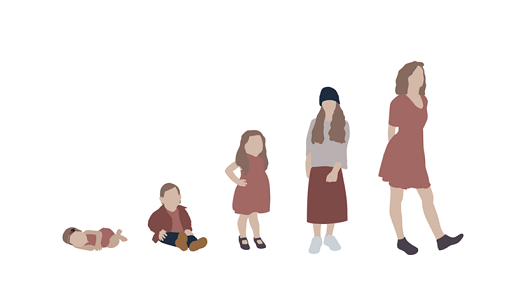

3.1: The ‘normal’ versus ‘non-normative’ childhood

From the late nineteenth century onwards, an unprecedented level of attention was paid to the study of children and childhood. This was especially true in the field of child psychology where a child’s maturation towards adulthood was considered to occur in a series of steps or stages, as shown in Figure 3.2 (Crafter et al., 2019). This model of childhood is deeply ingrained in Western society’s notion of what an ‘ideal’ or ‘normal’ childhood should look like. It is a model that promotes the expectation for the ‘ideal’ childhood as a time of innocence, play and socialising (Kessen, 1962, 1979). The ‘normal’ child should be dependent on adults for their care, and kept innocently free from the burdens of everyday life (Burman, 2016). In other words, the argument suggests that ‘childhood’ is a socially constructed notion that changes across space and time. This poses a challenge for children and young people whose life experiences sit outside of these ‘normative’ parameters.

The socially constructed child also presents a challenge for practitioners working with children and young people. Working with Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC) and migrant children shines a spotlight on how diverse and different children’s experiences of growing up may be. The notion of a child travelling alone and ‘seeking asylum’ does in itself transgress what we feel are the ideal parameters for how childhood should be experienced (Crawley, 2011). This can have concrete implications for the decisions that are made about young people’s lives. For example, whether they are believed to be under 18 years of age in an age assessment, if they should be placed in foster care or semi-independent accommodation, or whether they are considered to be overly ‘mature’ either because of physical appearance, actions or behaviours.

3.2: Who does the caring?

The dominant ideas about what childhood should look like, which you read about in Section 3.1, also influence how particular care relationships are framed. When we think about the care of children and young people, the focus is often on the role of adults caring for dependent children, such as the care a parent would give a child. As a social care practitioner, you may think about the corporate parenting responsibilities the State provides in loco parentis. In this formulation of ‘care’, care is done by adults for children and young people.

However, as you read in Section 2, care comes in many complex forms and an often-neglected form of care is that provided by young people. Research within the wider field of migration has shown that young people often have significant caring roles and responsibilities within the family, such as pitching-in with domestic work (Rogoff et al., 2014), helping to support the family finances (Heidbrink, 2014) or acting as a young translator or interpreter (Crafter and Iqbal, 2022). Of course, there is also a large body of research outside the field of migration that focuses on the role of young carers and the adult-like roles they sometimes engage with for family members (O’Dell et al., 2010).

The Children Caring on the Move project, though, was keen to explore another aspect of ‘care’, which was young people’s care of each other. If young people were no longer being cared for by their immediate kin, what caring practices and care relationships were they engaged in? Drawing on empirical evidence of children’s caring practices (Rosen et al., 2021), this literature conceptualises children as social actors actively caring for and in their communities. It suggests that whilst migration may be unusual or traumatic for some, it is the socio-political precarity under which children find themselves that makes their lives difficult (Chase, 2013).

Activity 3.3: Thinking about young people’s care of each other

Activity 3.3: Thinking about young people’s care of each other

Now, read the following quote from a young person we have named ‘Sara’ (the dots reflect short pauses in his speech), who brought along a picture of her friend to her care object interview. She was asked to describe her relationship with her friend. As you read her quote, think about how this might be framed as a caring relationship.

‘Okay. First, we know each other in Belgium for one year there because we stayed there to try to come here for one year…And when we try we came here by the lorry, the truck, the pickup. And when we need to go there, for example, sometimes if I am not feeling well, my friend doesn’t leave me and try to come to here. She stay with me. And she stay with me and try to the next day with anything like when we are tired, because we are tired we have to work for long hours. So she was always with me. Yeah. And she’s still with me now.’

INTERVIEWER: Can I ask one more thing? And please, only answer if you feel comfortable to, Sara, okay? Can you maybe tell us a bit about that support that you’ve given each other? So what did it look like, you know, when you were moving together to the UK? How did you support each other?

‘Everybody have like two people in Belgium when they are travelling. But when you go to try and to find the truck, first you need to go along journey from the place you stay. And then there is like walking in the like jungle. And we always go in the night-time. And if you are just by yourself, it’s scary. And we are always together and we go there. And even sometimes they will say like… the people say, “Come,” just one of us. If there is not enough space, they call one of us and then to try to the truck in her, the truck. And she never leave me. She always wanted to stay with me because she didn’t think just for herself. She think about me as well. Yeah, a lot of times she did like that.’

Discussion

The relationship between Sara and her friend reflects several of the ‘phases of care’ and their associated moral elements that you read about in Section 2.1. Sara repeatedly describes moments of feeling ‘cared about’ through the attentiveness of her friend, such as when she says ‘…if I am not feeling well, my friend doesn’t leave…’. Sara predominantly frames herself as the ‘care receiver’ and responds by recognising the empathetic concern shown by her friend, ‘She always wanted to stay with me because she didn’t think just for herself.’ It is hard to know how much this was reciprocated by her friend because we only have Sara’s narrative, but there is a sense of solidarity amongst the two friends which has endured as a care relationship over time.

3.3: Section summary

In this section, we have unpicked how we think about ‘childhood’ and how that can vary across time and context. We have focused on some of the key assumptions that are deeply embedded into societal views of childhood and explored the ways in which certain childhoods transgress or upset those ideals. In the next section, we are going to delve more deeply into what the professionals and practitioners in the Children Caring on the Move project thought about children’s care of each other.

Now, continue to 4: Professionals’ and practitioners’ perspectives of UASC’s care of each other.