Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:23 PM

Young lives: is now a good time to be young?

Introduction

Young lives – diverse, complicated, unique and significant – are a fascinating subject to study. The lives of children, young people and young adults are important to every society and their welfare, safety, health and happiness – their quality of life – are at the heart of every society and its hopes for a better, fairer future. As societies change, they need to consider what to do in response to the interests, priorities, rights and aspirations of children and young people and this gives rise to some vitally important questions. In this course, Young lives: is now a good time to be young?, you will be able to take a closer look at some of the recent and emerging reports and academic studies which are focused on young lives in the UK today and thereby to consider some of these important and often urgent questions.

This course is an adapted extract from the Open University course KE322 Young lives, parenting and families.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

demonstrate greater specialist knowledge and understanding of children’s and young people’s lives

have a greater understanding of the social, historical, political, geographical, demographic, cultural and philosophical influences on young people’s lives

draw on contemporarily relevant knowledge of how issues such as age, geography and class affect children and young people.

1 Regional difference and divergence

Early lives are lived within a complex interplay of education, wealth, health, family circumstances and experiences. But they are also affected by where we live and the resources available where we grew up (for example, good transport links or a swimming pool or a safe neighbourhood). While many of us might easily and readily identify how where we were born has influenced our lives, perhaps a more difficult question to answer is whether where you are born should matter. Keep this in mind as you do the first activity.

Activity 1 Does where you are born (still) affect your chances in life?

Human geography can play a significant role in understanding young lives. Anne Longfield, the Children’s Commissioner for England, has examined the North–South divide in England. (Although an English example is used here, data illustrating geographical divergence from another part of the UK could equally have been used.)

Read the following materials from Growing Up North:

- infographic: Time to Leave the North–South Divide Behind (Longfield, n.d.a).

- pp. 4–7 of the Executive Summary and Recommendations: Look North: A Generation of Children Await the Powerhouse Promise (Longfield, n.d.b).

Now answer the following questions:

- In what ways does it still matter where children are born?

- Why might these particular recommendations reduce the North–South divide?

Write your answers in the box below.

Discussion

Anne Longfield, as Children’s Commissioner for England, decided to focus some of her attention and resources on the north–south divide in England because of the clear geographical differences in things such as wages, jobs, GCSE achievement and engagement with higher education, which all play an important part in young lives.

Geographical differences are linked to divergence in equality of opportunity and while this is by no means a recent phenomenon, it is one important piece of the bigger picture. Longfield sees geographical differences like this as unfair and something that should not be accepted as inevitable. She describes the North–South divide as one component playing a part within a complex set of interactions, or dynamic, between education, wealth, health, labour markets, family aspirations and transport links that negatively affects many children’s and young people’s lives.

In the report’s recommendations, you can see a variety of ideas for addressing the damaging effects of regional inequalities: putting children at the heart of regeneration and urging additional investment to support local councils are probably foreseeable recommendations, but there are others here too. Changes need to be made for children and young people of different ages; strengthen early intervention services, increase early identification of special needs, provide greater leadership from key schools (the Northern School programme recommendation). There is also a recommendation to put in plans to prevent young people from dropping out of education early. The report recommends a closer relationship between schools and local employers. It also recommends that arts, culture and sports are provided, in the first instance, to children and young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. Addressing geographically based opportunities and services for children and young people like this has real potential to address disadvantage.

It would seem that where you are born today remains a significant determinant of life choices and chances. For example, by the age of 5, less than half (49%) of children born into the poorest families in the north of England achieve a ‘good level of development’, which compares with 59% of children living in poverty in London (Clifton et al., 2016). Also, just a third of those children who receive free school meals in the north go on to achieve the standard of five GCSEs at grades A*–C, including English and Maths (Clifton et al., 2016). And this situation is set to get worse. Demand for skilled workers in the north of England is forecast to increase, with three-quarters of the 2.4 million new jobs expected to be available in 2022 requiring A levels or equivalent in training (Clifton et al., 2016).

Of course, the picture is more complex than that. So, for example, while London still has the highest levels of child poverty in the country (Child Poverty Action Group, 2018), it has experienced a remarkable, rapid increase in newborn life expectancy (Office for National Statistics, 2017). This could be as a result of the selective migration of more healthy individuals from more deprived areas of the UK to London (and the south-east) (Office for National Statistics, 2017).

However, life expectancy is now actually falling in some parts of the UK (Office for National Statistics, 2017) and being born in what the Social Mobility Commission has called one of the UK’s ‘cold spots’ (Social Mobility Commission, 2017) means low wages and fewer routes into good jobs, leaving people trapped in poverty. You will look at social mobility later.

2 Intergenerational unfairness

While many inequalities are long-standing, and different ways of looking at divergence can emerge, there are also more recent developments. An example of a new inequality relates to ‘intergenerational unfairness’. Some people believe that a new trend has developed where older people’s lives are prioritised over those of younger people. ‘Baby boomers’ (those born between 1946 and 1964) have supposedly been prioritised over ‘Millennials’ (typically those born between the early 1980s and the mid-1990s to early 2000s) and that the older generation have ‘pulled up the ladder’ (most often referring to the housing ladder) behind them, leaving the younger generation with no hopes of a mortgage or a good pension, and with an environmental catastrophe (climate change) to deal with and pay for.

In the next activity, you will look at evidence of the argument that young people today face a ‘perfect storm’: a combination of low wages, precarious employment, an insecure labour market, student debt and high housing costs. When you listen to some young people today, the feeling is that it is not a good time to be young and that things were much better for their parents and grandparents. They believe that they can’t ‘get on with their lives’ until intergenerational unfairness is fixed.

Activity 2 Intergenerational unfairness

First, watch Video 1.

Transcript: Video 1 Intergenerational unfairness

The Resolution Foundation is a ‘think tank’ working to improve the living standards of low- to middle-income families in the UK; it has drawn together a range of people to debate this issue and devise a way forward. Don’t forget that if you are particularly interested in the work of a specific organisation such as this one, you might want to follow their Twitter feed: @resfoundation.

Now read:

- Why intergenerational unfairness is rising up the agenda, in 10 charts (Gardiner, 2017).

Do you agree that intergenerational inequality is real? If not, why not? If so, is it a problem?

Discussion

There certainly are differences between generations, but you can argue that while the evidence about jobs, pay, housing, lower incomes and less spending is clear enough, other issues would be relevant in any discussion of whether life is worse for young people today; living standards were lower, and health care and health outcomes were certainly worse for older generations, while younger people benefit from the profound social changes brought about by previous generations.

Yet the intergenerational dimensions of inequality cannot be ignored. Perhaps the most glaring example of this is that, as some young people will inherit property (and perhaps other assets) and some people will not, wealth inequality is constantly self-perpetuating, across the generations.

Perhaps it is too easy to focus on the division and conflict between generations. Lots of intergenerational support and help continue, for example, the ‘bank of mum and dad’ often helps with university costs, while many children and young people still provide care and support to older generations.

Discussions like this about whether this is a good time to be young can be very revealing; perhaps we need more of them.

3 Social mobility

A key indicator of a meritocracy is the extent to which a society enables social mobility. Social mobility implies a more level playing field and fairer opportunities for individuals to change social or economic class or to achieve different status and outcomes than might otherwise be predicted for someone with their particular geographical, cultural or parental background. The education system could, for example, be used to this end. However, despite being a UK government priority, sustained and widespread social mobility remains elusive.

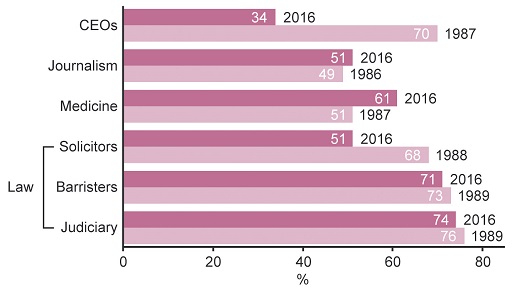

One way of measuring social mobility is to examine attained professional status in relation to an individual’s educational background. In the UK, it is important to bear in mind that private (also referred to as independent) schools tend to be used by families on high incomes to educate their children. High incomes are also commonly found in specific professions. Therefore a cycle of privilege occurs, with high income professionals sending their children to private schools and privately educated pupils going on to become high income professionals. This correlation between high income professionals and private school education can be observed statistically. The following graph is taken from the Social Mobility Commission report (Social Mobility Commission, 2017, p. 79) and shows the percentage of people at the top of a sample of professions who went to independent schools, at two points in time, the late 1980s and 2016.

The graph provides a mixed picture in terms of social mobility. CEOs of companies come from a wider range of educational backgrounds (one factor may be that the number of companies has increased since 1986). There has been, however, an increase in the proportions of privately educated individuals entering journalism and medicine and only minimal change in barristers and the judiciary. The next activity looks at a real world example involving a person from a non-private school background who defied the odds and became a barrister.

Activity 3 Adventures in social mobility

Hashi Mohamed came to the UK as a refugee aged 9. His identity as a poor Muslim Somalian could place him in a position of multiple disadvantages. During his childhood in the UK, he lived in crowded housing and didn’t achieve anything remarkable within school. However, Hashi now works as a barrister, considered to be an elite profession mainly occupied by people from privileged, privately educated backgrounds. Listen to Audio 1 in which Hashi discusses his change in situation.

Transcript: Audio 1 Adventures in social mobility

Discussion

Hashi offers an individualised explanation for his success that he describes as ‘social confidence’. One of the young people in the audio recognises and affirms that social confidence is a quality that many people she has met from private schools possess. Hashi explains how his social confidence emerged in part by reflecting on the possible life he might have lived and the opportunities presented to him as a refugee in a new country. Another of the young women talking with Hashi in the audio casts some doubt on his self-confidence message and argues that in fact adversity can cause some people to lose confidence.

Hashi also refers to ‘character’. This is a subjective concept that Hashi links to the skills and attitudes developed by people who face adversity. Although he doesn’t use the term, this would appear to have similarities with the concept of ‘resilience’ or ability to bounce back in the face of adversity. Far from being an inherent individual quality, ‘resilience’ is conventionally understood to emerge as the product of social relationships and experiences.

Finally, one of the young women identifies ‘adaptability’ as a quality that can help with social mobility. Hashi affirms that there is a requirement to be like a chameleon and adapt one’s behaviour to the context. This appears to have some similarities with ‘cultural capital’. ‘Cultural capital’ essentially involves possessing and applying a certain type of legitimate knowledge to a specific context. So, for example, to do well in the legal profession, it would be useful to have an awareness of the legal language, as well as the cultural and social topics, that many barristers share. Such legitimate knowledge may help build rapport and trust, which in turn may open up opportunities.

4 Teenage kicks?

The image and idea of ‘being a teenager’ are part of ‘Western’ received wisdom, but it wasn’t always that way. The next activity considers how the idea of ‘the teenager’ came to be so widespread. It also considers the ways in which certain places, such as the bedroom, have become central to teenage experience and identities. Working through the activity will allow you to become more familiar with how young people come to be recognised as a distinctive collective entity. It will also introduce you to the way academic research investigates such social phenomena.

Activity 4 Teenage dreams are hard to beat

Part 1

The discovery and invention of the teenager in the mid-nineteenth century, and the way the concept took hold of the popular imagination throughout most of the twentieth century, are the subjects of Jon Savage’s book, Teenage: The creation of youth 1875–1945 (Savage, 2007).

Watch Video 2 ‘Teenage’, in which Jon Savage describes making a film for TV (Teenage, 2013) about his research for the book:

Transcript: Video 2 Teenage

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Part 2

Now read this short article on youth movements written by Matt Wolf, another of the makers of the film Teenage (2013):

- 10 Youth Movements That Changed History (Wolf, 2014)

Part 3

Complete the following drag and drop activity, to match the youth movements to the place they are associated with and their formation dates.

Discussion

As one of the female narrators in the video notes, ‘A lot of people try to shape the future. But it’s the young ones who live in it.’ This observation resonates strongly with events such as the UK referendum on leaving the EU. Young people tended to vote ‘remain’, or could not vote at all, but they will live in the future created by the votes of older people.

Savage’s observation on how frequently pop culture starts with ‘frenzied young women’ and the role of young women’s diaries and journals in providing a crucial record of the experience is a reminder about how history is constructed. As someone who frequently writes from ‘queer’ perspectives, Savage is sensitive to the way women play prominent roles in history but are frequently written out of it.

The images we have of youth depend on this history and what is selected, what is left out and whose stories are told. As the film suggests, youth is a social construction that inevitably involves ideas about gender, race and power. This is self-evident in an organisation such as the Hitler Youth that became notorious for its explicit alignment with the development of fascist political power in Germany. The complicity of the Boy Scouts in British colonial projects may be less explicit and less notorious, but it was no accident of history.

Studies of other less formal youth groupings, such as Hippies, Punks, Dreads, Goths or Riot Grrrls can also be fruitful and are the subject of distinctive academic disciplines, such as sub-cultural studies (see, for example, the Interdisciplinary Network for the Study of Subcultures, Popular Music and Social Change (University of Reading, n.d.).

5 Teenage bedrooms

In much of the early studies of young people’s sub-cultures (Willis, 1977) the focus was on boys and young men in schools, the streets or the workplace. Angela McRobbie (2000) criticised this work for excluding young women and sidelining their experiences. McRobbie suggested young women were invisible to the researchers because their social life was more likely to be centred on their bedrooms, away from the gaze of researchers who were mainly young-ish men who explored a world familiar to themselves – schools, playgrounds, street corners and workplaces, but neglected the more domestic sphere of home life.

The next activity builds on McRobbie’s insights by examining the new spaces of teenage life and what they can tell us about families, parenting and social values.

Activity 5 A room of my own

In this extract from the BBC radio show Thinking Allowed, two academics discuss their research about how young people’s bedrooms are central to their emerging identity and sense of space and place.

Listen to the following audio.

Transcript: Audio 2 Teen bedrooms

INTERVIEWER

SHAWN

Now read the associated webpage, Get out of my room! The truth about a teenager’s bedroom (BBC Radio 4, n.d.).

- Which is your favourite of the six elements defined as significant?

- What are the reasons discussed in the programme for the new significance of bedroom life to teenagers?

Make a note of your thoughts on the issues raised in the programme.

Discussion

The programme opens out important questions about the way ideas around young people’s bedrooms have shifted. These changes reflect, and are driven by, the way personal spaces are shaped by economic developments, and the social relations of gender and class. Even questions once associated with public spaces, such as young people’s involvement in crime, have become tangled in these changes. According to some criminologists (Pitts, 2013), the decline in recorded levels of youth crime may be at least partially attributable to boys and young men spending so much more of their time indoors, in bedrooms, among the adrenalin-fuelled thrills of gaming consoles. These, it is argued, have replaced the edgy thrills and status rewards of stealing cars and other forms of street crime with their virtual equivalent. The researchers provide insights into the ways social order and social values are played out in teenage bedrooms. The domestic sphere has been transformed, partially by electronics, but also by the decline of public spaces where teenagers can mix and play safely and collectively, such as youth clubs.

6 Whose playground is it anyway? Social class, social power and being young

In this course, some activities will mean that you are exploring how you feel about youth and young people, how they affect you in various personal ways and how these ‘affects’ may shape your perspectives. Recognising ‘affect’ as an important dimension of social life helps to identify the way emotions, desires and feelings operate at the core of the political dynamics that shape our lives (Gatens and Lloyd, 1999).

There are part of what the African philosopher Achille Mbembe refers to as a new ‘politics of viscerality’ (Mbembe, 2016). An appreciation of ‘affect’ forms part of a psychosocial approach to understanding contemporary life. It emphasises how emotions, such as anxiety, play a productive role in personal value systems and help to reproduce certain social realities, such as hierarchies around class, gender and race or, conversely, help to dismantle them by building more egalitarian social horizons.

6.1 Hiding in the light: rich young lives

Young working class people have been routinely held up for scrutiny in social research and social policy, and they are implicitly held to account for their various behaviours. However, the richer you are the more likely you are to escape being seen as a problem to society (Du Bois, 1903) or a burden to be managed by social interventions of one kind or another. If you are rich, you are less likely to be known by names or labels you didnt ask for, you are of less interest to government agencies such as social services or the police, and you are less likely to be researched. Thinking critically, you might ask if these issues are connected.

The next reading is focused on the lives of young people who don’t usually feature in social policy research papers. It concerns young people who are usually almost invisible to social researchers. They are young people who have attended the schools pictured in Figure 3, or ones like them. They might be described as ‘well off’, ‘the elite’, ‘posh’ or simply ‘rich’.

The idea of ‘cultural capital’ and its relationship with the reproduction of class is now widely accepted but there remains a rich seam of research able to reveal just how different status groups are currently evolving and adapting. In this next piece, academic Daniel Smith reflects on the implications of his study into how an albeit changing elite still finds ways to effectively and efficiently reproduce itself.

Activity 6 The Branded Gentry

Read the article ‘Britain’s elites: new lions, old foxes’ by Daniel Smith.

As you read, consider how particular niche sports and certain marketing brands can become emmeshed in the lives of some young people and what the consequences of this might be.

Discussion

While playing polo appeared to struggle a little with its elitist tag, the Jack Wills Brand and the name ‘Jack Wills’ consciously adopted an elite group identity in British society, namely the 18–23 demographic of the ‘upper-middle classes’. This group of young people, wealthy, privately educated and often having attended the ellite group of public schools (known as the Clarendon group) and going on to, again, a particular group of UK universities are still able to use patronage and sponsorship opportunities (but these levers of power need to be constantly brought into the light). Here, Smith discusses how the British educational elite institutions have been able to adapt, allowing a more diverse intake and embracing a meritocractic ethos. This research reveals one way in which involving certain marketing brands (or particular low participation sports) produces the networks among elite groups that are so advantageous to their young people.

If you’re interested, you can hear Daniel Smith in the following Radio 4 programme: Thinking allowed: fashion and class (from 14:07 to 27:44).

Research and social studies are often focused ‘down’ toward people at the bottom of the social hierarchy; relatively powerless people to whom ‘things are done’ or to whom services are provided, to put it more politely. Those with power often remain less well scrutinised. This can be as true when it comes to race, gender and sexuality as it is for class. White people, for example, are less frequently seen (by white people) as a distinctive category and still rarely become the objects of social studies as white people.

6.2 Not in education, employment or training?

If the previous activity was concerned with those young people who rarely feature in social research and social policy, this last activity returns to more conventional subjects: young people whose wellbeing appears to be ‘at risk’, or who are seen to present risks to society because they are not engaged in any of the conventional avenues of adolescent progression – school or college, waged work or training. They are referred to as ‘NEETs’ because they are ‘Not in Education, Employment or Training’.

As children become young people and seek more autonomy for themselves, they may face growing risks of poverty and material deprivation. According to Daniel Sage (2016), almost a third of people (32.6%) in the UK aged under 18 were at risk of poverty or social exclusion, while 10.5% were experiencing material deprivation. By contrast, the corresponding figures for older people were 18.1% and 1.9% (Social Justice Index (SJI), 2015, cited in Sage, 2016). Tens of thousands of young people will fail to receive the kind of support they need to get into the labour market.

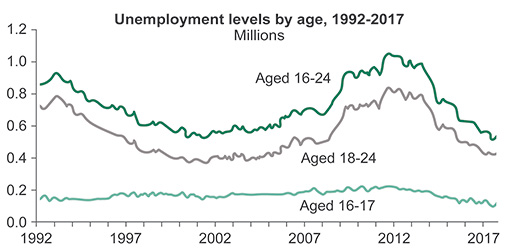

The number of unemployed young people has fallen from the peak levels of 2012 (see Figure 5 below), and although the proportion of young people as a percentage of the general population has been falling for some time, the proportion of young people (aged 16–24) who are unemployed has also fallen from 13.1% in November 2016 to 11.9% in Nov 2017 (House of Commons Library, 2018a). By comparison, in 2016, the unemployment rate for all those aged 16 and above was just 5%, suggesting that unemployment is a much bigger problem for young people than for anybody else. Unemployment is a particularly acute problem for young black people – over the period from December 2015 to February 2016, the unemployment rate among black 16–24-year-olds was 27.5%, more than double the rate for young white people (Unison, 2016).

Some of the challenging circumstances faced by young people are examined in the next activity.

Activity 7 Not so Nice and NEET

a.

making successful transitions to adulthood

b.

their overall wellbeing

c.

their average lifetime income

d.

avoiding criminal pathways

The correct answer is a.

a.

bleak and alienating

b.

a lot of laughs

c.

worth a lot of money

d.

unskilled and unending

The correct answer is a.

a.

disordered or suspended

b.

clearly signposted

c.

smoother and more enriching

d.

a career opportunity for moral entrepreneurs

The correct answer is a.

a.

Over half

b.

About one third

c.

Less than a quarter

d.

Does anybody care?

The correct answer is a.

a.

1996

b.

1949

c.

1968

d.

1918

The correct answer is a.

a.

Depression, isolation, anxiety and over-eating.

b.

Chronic fatigue syndrome, intolerance, nail biting and anxiety.

c.

Amnesia, depression, teenage angst and total torpor disorder.

d.

Nail biting, intolerance, chronic fatigue syndrome, isolation and over-eating.

The correct answer is a.

a.

little or no advantage when seeking employment

b.

significantly reduced self-esteem

c.

a higher than average elementary qualification

d.

several formatted certificates of general worthiness

The correct answer is a.

a.

Kite-marked partnerships between local authorities, employers and education institutions.

b.

Adult minimum pay.

c.

More funding.

d.

More youth centres.

The correct answer is a.

a.

the most vulnerable

b.

the hard to reach

c.

the right age group

d.

those more at risk of harm

The correct answer is a.

a.

Driving up labour market standards

b.

Fixed training budgets.

c.

Making things better for everybody.

d.

A Charter for Youth.

The correct answer is a.

Increasing numbers of young people find themselves in precarious economic circumstances in which it is very difficult for them to fend for themselves, thrive and flourish. They may be seen to pose more of a threat to society than a symbol of its failures. When this happens, the policing of young people becomes an urgent priority for government.

Conclusion

In this free course, Young lives: is now a good time to be young?, you have explored some of the contemporary research studies offering engagement and insight into children and young people’s lives today. Hopefully, you have been able to find in this course some disruptive thinking, challenging some of the more established approaches and lines of enquiry. Hopefully you will agree that we constantly need to remain open to new ideas and to ensure we refresh and reinvent research methodologies if we are to be able to answer of the important questions embedded in any consideration of young lives today.

This course is an adapted extract from the Open University course KE322 Young lives, parenting and families.

Glossary

- Affects

- The term affects refers to the way social and political processes are physically experienced.

- Human geography

- A branch of geography that focuses on the interrelationships between people, places and environments.

- NEET

- A young person who is Not in Education, Employment or Training.

- Psychosocial approach

- A psychosocial approach combines the methods and insights of psychology, psycho-analysis and sociology.

- Queer

- Queer theory and queer perspectives are derived from questioning the critical role of gender, sexuality and desire in society.

- Russell Group

- The Russell Group is a collection of 24 universities in the UK that pride themselves on the quality of their research and training.

- Social mobility

- A sociological term describing the movement of individuals and groups between social classes or other types of social stratification. Upward social mobility or the opportunity to move from a lower to a higher class is a common policy goal for governments in Western democracies.

- Sub-cultural studies

- An academic discipline that studies particular groups of people in modern societies. The groups are often composed of young people.

- Teenager

- Someone between the ages of 13 and 19.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Pam Foley. It was first published in October 2019.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

Course image: © DisobeyArt/iStock

Figure 1: © Crown copyright, Social Mobility Commission, Reproduced under the terms of the OGL, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence

Figure 2: Teen group drops by for a visit at the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts. https://artmuseumteaching.com/2012/10/28/why-museums-dont-suck/ This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial-No Derivatives Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Figure 3 © Greg Balfour Evans / Alamy Stock Photo; © Skyscan Photolibrary / Alamy Stock Photo; © Robin Bell / REX / Shutterstock; © Justin Kase zninez / Alamy Stock Photo.

Figure 4: © Buzz Pictures / Alamy Stock Photo

Figure 5: Briefing Paper, Youth Unemployment Statistics, House of Commons Library, 2018, Reproduced under the terms of the OGL, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence

Audio-visual

Video 1: Intergenerational Foundation

Video 2: © Guardian News & Media Ltd 2019

Audio 1: © BBC

Audio 2: © BBC

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University.