Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 21 November 2025, 7:12 AM

Play, learning and the brain

Introduction

This course examines the subject of brain-based learning, with a particular focus on the development of the young child's brain and is of particular relevance to those who work with young children. We begin by looking at the structure and functions of the brain, and the impact that sensory deprivation can have on these. We consider the implications of current understandings of brain development for teaching and learning, particularly in an early years setting, and finish by exploring the value of play (particularly outdoor play) in children's learning and the development of their brains.

This course provides a sample of postgraduate study in Education, Childhood & Youth qualifications.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

demonstrate an awareness of current understanding of the structure and function of the brain

understand and critically analyse the linked concepts of brain-based learning and brain-based education

understand the role of play in brain development

recognise practical strategies for developing the curriculum to facilitate children's learning through play and other rich learning experiences.

1 Play, learning and the brain

Our brain-building starts in utero and we are all born with billions of neurons — specialised brain cells designed to transmit information to other nerve cells around the body. Rapid brain growth means that by age two our brains are approximately 80% of adult weight, reaching 90% of adult size by age five.

‘Brain-based learning’ (BBL) is receiving increasing attention in the popular and professional fields. But what exactly is it? Before we explore the idea further it is important to understand the brain as we currently know it. The diagram of the brain (below) will remind you of some key ideas about its various areas and functions.

Our brain and the spinal cord together make up our central nervous system. The spinal cord goes from the brain down to the lower part of the back. It is responsible for taking messages to the brain from the rest of the body, and from the brain to the rest of the body.

When we look at the brain image we can see three main parts:

- the cerebrum

- the cerebellum

- the brainstem.

Each of these parts controls a number of important functions.

The cerebrum is the largest part of the brain and it is found at the front of the head. It controls our sense organs – touch, vision, hearing, temperature – and it initiates and co-ordinates movement. It also has a role in problem solving, reasoning, emotions and learning. All thoughts, memories, and imagination occur in this region. In this diagram the cerebrum has been displayed to show the lobes and their function.

Activity 1

Take a look at some of the ‘facts’ we know about the brain by taking part in this light-hearted quiz.

The very rapid growth of the brain during the first years of life raises some important questions about the quality of early experiences for children's overall development.

Before you move to the next section you may like to think about what is meant by the term ‘developed’, and whether the quotation from the Royal Foundation Centre for Early Childhood at the top of this page means that the brain can only develop a little more after the age of five.

2 What is brain-based learning and teaching?

Neuroscientists now have more sophisticated ways of examining living brains than was ever possible before. It is now possible to obtain images of the brain that show activity as it occurs. The importance of the first years of life has always been recognised by early years practitioners but the new information about the brain deepens our understanding about why this might be.

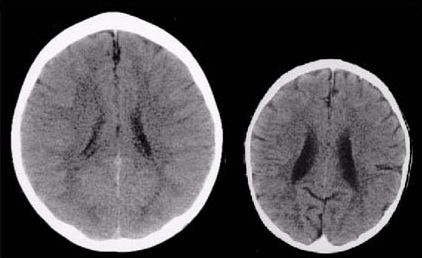

Research from the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2012) and Perry and Pollard (1997) has reported on the effects of sensory stimulation, or the lack of it, on early brain development. Using data from CT scans, physical measurements and documentary sources they explored the brain development of a group of neglected children. As an example of what can happen in an extreme case of sensory deprivation, Perry and Pollard published the startling images shown below.

These images illustrate the negative impact of neglect on the developing brain. The CT scan on the left is from a healthy three-year-old child with an average head size (50th percentile). The image on the right is from a three-year-old child following severe sensory-deprivation neglect in early childhood. This child's brain is significantly smaller than average and has abnormal development of the cortex (cortical atrophy) and other abnormalities suggesting under-development and mal-development of the brain. The contrast is marked but it is important to remember the comparison is with a very extreme example.

Research like this suggests that new information about how the brain works will help us to develop more effective learning strategies. Now complete Activity 2, which will take you more deeply into the key ideas behind brain-based learning and the ways these can be linked to educational practices.

Activity 2

Click on the link below to read the first article Brain Development and Early Learning’. Keep a note of any points that are new to you or that you found surprising in any way, as you will need these for the next activity.

Article 1: ‘Brain Development and Early Learning’ (Wisconsin Council on Children and Families, 2007)

Next, click on the link below for the second article ‘What Is “Brain-Based Learning”?’, which looks in a little more detail at brain research and links this to learning and teaching. It suggests ways in which educators could enhance their practice by drawing on this new information. Look particularly at the Twelve Design Principles and at the ways in which it is suggested learning can be maximised. Keep a note of three points that interest you in this reading and which relate specially to young children.

Article 2: ‘What Is “Brain-Based Learning”?’ (Chipongian, 2004)

After you've completed the reading, make some further notes in response to the following:

- evaluate your own provision according to the Twelve Design Principles

- consider how you would make changes to enhance learning

- note any points about brain development that are particularly pertinent to you and your setting.

3 Are there any problems with adopting brain-based approaches to education?

It is apparent that there is a great deal of overlap between what is termed BBE (brain-based education) and what has been considered ‘good’ early years practice (e.g. contextualised learning).

But are there any problems with the way in which research into brain development and function has been used by educationalists to develop the distinctive approach labelled ‘brain-based education’?

As could be anticipated with any new idea, BBE has both its advocates and others who urge practitioners to take a more cautious approach. Activity 3 presents some alternative perspectives and may help you decide which view you find most convincing.

Activity 3

To help you decide, click on the link below to read an extract from an interview with Renate Caine, an advocate of connecting brain-based learning to education.

Article 3: ‘Maximizing Learning: A Conversation with Renate Nummela Caine’ (Pool, 1997)

Then click on the link below to read Fran Ellers' account of a discussion with Charles Nelson, a brain researcher who urges a more cautious approach.

Article 4: ‘New research spurs debate on early brain development’ (Ellers, 2004)

Take another look at your notes to Activity 2, and where applicable, amend them to include ideas from these readings.

Optional reading:

In 1999, John Bruer wrote a very important critique of brain-based learning and the links being made between this research and early childhood educational policy. You may be interested in reading more about his views, which you find by clicking the link below.

4 Play and learning

‘In play, the child always behaves beyond his average age, above his daily behaviour.

In play, it is as if he were a head taller than himself.’

(Vygotsky, 1978)

Why are early years practitioners convinced about the value of play?

It is interesting that although writers are able to state what children may learn through play in terms of dispositions, knowledge, skills and attitudes, there is less written on why play rather than any other form of activity is particularly valuable to the young child and their developing brain. BBL begins to address the issues of ‘quality and play’, as Activity 4 explores.

Three teaching elements are said to arise from the principles underpinning brain-based learning taken from the Wilson and Spears article, which you read in conjunction with Activity 2:

orchestrated immersion in complex experiences

relaxed alertness

active processing (i.e. meta cognition).

There are many ways in which we can make judgements about ‘quality’ in early years settings including, for example, environmental factors, staff qualifications, staff turnover and the appropriateness of the programme provided. Most importantly, the learning experiences provided need to be developmentally and culturally appropriate in meeting children's needs. Additionally adults and children need to be able to interact with warmth in responsive and reciprocal ways.

To decide how you feel play can fulfil these criteria you should now go to Activity 4.

Activity 4

Observe a child engaged in what you would regard as high quality play.

As you do so, make notes describing the child's level of involvement, commitment, interest, perseverance and emotional state.

5 Outdoor play and learning

Early years practitioners have always argued strongly for children to have the opportunity to play in both indoor and outdoor environments. But currently, adult fears appear to be making outdoor play an ‘endangered activity’.

The following list, adapted from Kemple et al. (2016), offers some good reasons for making sure young children have the opportunity for outdoor play time.

- Health and physical development: in recent years, childhood obesity rates around the world have increased. To combat this many countries are recommending outdoor activity for all children. Physical play outdoors provides important opportunities for the development and refinement of locomotor skills as well as fine motor skill. Vigorous physical activity increases lung function, contributes to muscle, bone and joint health and strengthens the heart. It also increases the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the brain, benefiting brain function.

- Appreciation of nature and the environment: learning in an outdoor environment allows children to interact with the elements around us and helps them to gain an understanding of the world we live in. They can experience animals in their own surroundings and learn about their habitats and lifecycles.

- Development of social skills: researchers found that when part of an asphalt play area was transformed into a more natural area with vegetation, children’s social behaviour changed; they showed less aggression when playing in the natural area than on the asphalt area. Another study that compares children’s behaviour on natural vs. less natural areas of a play environment found that children not only spent more time playing in the natural space and utilised the traditional equipment less, but also engaged in more social interaction.

- Encouragement of independence: the extra space offered by being outdoors will give children the sense of freedom to make discoveries by themselves. They can develop their own ideas or create games and activities to take part in with their friends without feeling like they’re being directly supervised. They’ll begin to understand what they can do by themselves and develop a ‘can do’ attitude, which will act as a solid foundation for future learning.

- Understanding of risk: being outdoors provides children with more opportunities to experience risk-taking. They have the chance to take part in tasks on a much bigger scale and complete them in ways they might not when they’re indoors.

Activity 5 now asks you to consider your own setting and identify the contribution your outdoor play provision makes to learning.

The activities that can be provided depend on the type of setting, the resources available and the practitioner's views about the place of outdoor activities in the overall development of the child.

Activity 5

There are links to two articles below. Article 5 is of a general nature, while Article 6 focuses on school contexts.

Select the article on outdoor play that you feel is most appropriate for your setting.

Article 5: ‘Outdoor Experiences for Young Children’ (Rivkin, 2000)

Make a list of the ways in which outdoor play is of specific value when considering children's learning and the development of their brains.

Draw on:

- what you know about the development of the brain

- what you know about the ways in which children play outdoors.

You may find it helpful here to have an observational record or short video of children playing outdoors in your setting.

When you have done this, review and evaluate your outdoor play provision using the list of points you made at the start of this activity. If it is possible to work with a colleague, please do so.

Conclusion

This course provided an introduction to studying Education, Childhood & Youth qualifications. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance and helped to improve your confidence as an independent learner.

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

This course was prepared for TeachandLearn.net by Dr Naima Browne, who is a specialist in Early Years education. She has taught in nursery and primary schools, been an early years advisor and university lecturer, and published widely in the field.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: Georgie Pauwels in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Key images: Getty Photodisc.

Two brain scans: copyright © Bruce D. Perry, M.D., Ph.D.

Rivkin, M. S. (2000) ‘Outdoor experiences for young children’. www/ael.org/eric/digests/edorc007.htm. ERIC Clearinghouse on Rural Education and Small Schools/US Department of Education.

Pool, C. R. (1997) ‘Maximising learning: A conversation with Renate Nummela Caine’, Educational Leadership, Vol. 54, No. 6, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD). Copyright © 1977 by Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Wilson, L. O. and Spears, A. (2003) ‘Overview of brain-based learning’. www.uwsp.edu/education/1wilson.

National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education (2002) ‘Recess and the importance of play: a position statement on young children and recess’ [Online]. Available at www.naecs-sde.org/policy

US Department of Education (1997) ‘Making connections: how children learn’, Read With Me, September 1997. www.ed.gov.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University