Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 2:43 PM

Session 1: ‘A crisis in context’

Introduction

It is possible that you are taking this course because you are worried about a young person close to you, or because you are concerned by adolescent mental health issues in general. What do you already understand about adolescent mental health? Are communities actually facing a mental health crisis, or is this a crisis that is being blown up in the media? To get started on this topic, listen to Audio 1 in which a parent talks about their experience of trying to understand what is happening in the life of their adolescent child.

Transcript: Audio 1: Parent experiences

Mental health problems can manifest in different ways and generally speaking becomes problematic when it interferes with some aspect of everyday life, including; the ability to learn, to feel, express and manage a range of positive and negative emotions, the ability to form and maintain good relationships with others and to manage change and uncertainty (Mental Health Foundation, 2020).

In the opening audio you heard a parent describe some of the difficulties that her child experienced leading up to a diagnosis of OCD and the value of treatment in providing much needed support. Of course, individual experiences will differ and will reflect the mental health challenges that a young person is facing. The most common mental health problems diagnosed for young people globally include anxiety and depression, often termed emotional disorders, with an increase in self harming behaviours and rates of suicide amongst young adults.

The language used to discuss mental health issues varies and different definitions exist including; mental health, mental health problems and mental illness. These terms are still hotly contested and as you read you will discover a little more about how they shape perspectives and experiences. As the course proceeds you may find that your opinion on what mental ill health is shifts or that how you understand emotional distress in adolescents gains depth.

In this first session, you will consider some statistics showing the extent of mental health issues in young people in the UK, and read about what people actually mean when they talk about ‘mental health’. Terminology and attitudes about mental health have changed dramatically over recent decades, as have the policies and practices designed to help people who experience these issues and those who support them.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this session, you should be able to:

describe the scale of adolescent mental health issues

recognise that mental health is part of the umbrella concept of health

describe how people’s understandings about mental health have changed over time

outline the UK mental health policy developments that affect families.

1 Adolescent mental health in context

Statistics can be baffling if they are presented without their full context as understanding this can help us understand what the numbers mean. To get you thinking about context, carry out the first activity now.

Activity 1: The size of the issue

Step 1: If you had to guess how many children were experiencing mental health issues at any one time, which one of these figures would you choose? Click a percentage figure and read the comment. There is a long description button below the figure if this is easier to learn from.

Discussion

As you will discover, all these figures are correct in some way, but it depends on the age of the child and what we mean when we say ‘mental disorder’ as well as where and when we are counting these issues. For example, all the figures presented here come from a large survey of the mental health of children and young people in England, which was carried out in 2017. A survey of a different country in another year is likely to produce different figures.

It is also helpful to know how the figures were obtained, for example, whether it was a large survey or a handful of interviews.

Clearly, Interactive Figure 2 shows that something is happening between the ages of 2 and 19, as the rates of mental disorder increase but what might be behind this increase? Our best evidence suggests that it is likely to be the result of a complex, dynamic mixture of physical and social development occurring within particular settings. This course examines what happens roughly between the ages of 10 and 19. This period of time in a young person’s life is sometimes called adolescence.

The statistics you just looked at showed the situation in 2017. Did you perhaps ask yourself, ‘is that better or worse than previous years?’, and ‘What’s the situation now’? You’ll consider these types of time-related trends next.

1.1 The trends

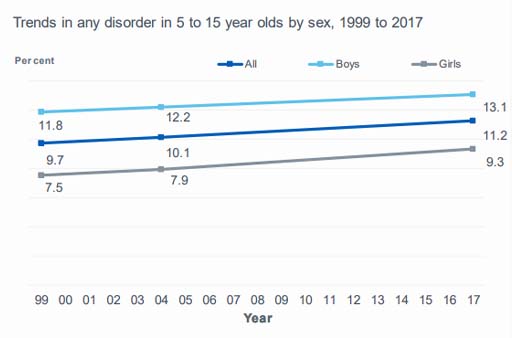

Media headlines frequently announce the existence of a global mental health crisis and that mental health issues in adolescence are on the rise. Is the mental health of young people really poorer than it was, say 20 years ago? Until the 2017 survey, presented in the first activity, data on under-fives and 16 to 19-year-olds was not collected, so trends over time are only available for the age range 5-15 years. In the next activity, you’ll look at the graph in Figure 3, which shows data from surveys of the mental health of 5 to 15-year-olds in England carried out in 1999, 2004, and 2017.

Activity 2: Examining the trends

The dark blue line, showing the average between boys and girls, indicates that in 2017 11.2% of 5 to 15-year-olds reported at least one mental health ‘disorder’.

In the first activity, you saw that 12.8% 5 to 19-year-olds had at least one mental health ‘disorder’ in 2017.

Can you see why the percentages are different?

Discussion

The trends graph is based on 5 to 15-year-olds and the figure in Activity 1 was based on 5 to 19-year-olds, a wider age group. We know that 17 to 19-year-olds had the highest incidence of mental disorder (16.9%) so when added to the statistics for 5 to 15-year-olds, they will raise the overall average. It’s important when looking at trends over time that the data sources are consistent. In this case, the NHS Digital team needed to pick out the 5 to 15-year-olds from the 2017 data to make the comparison with the previous surveys.

The graph you’ve just looked at shows a steady increase in mental disorders since 1999. There is a marked difference between boys and girls, with a noticeably higher percentage of boys experiencing a mental disorder compared with girls. Looking at this graph, you may conclude that we should be more concerned about boys than about girls. However, these figures, which pool all ages, are hiding some interesting detail!

1.2 Trends by age group and sex

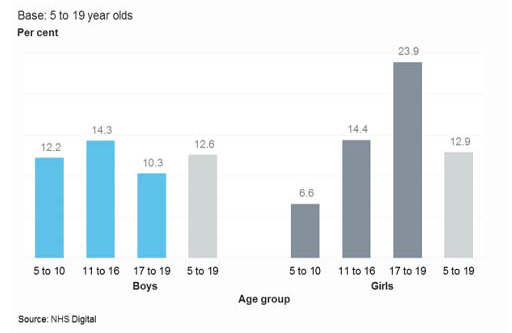

In the next activity, you’ll look at the two graphs in Figure 4 separating the 2017 data into smaller age groups.

Activity 3: Examining sex differences

According to the figures in these graphs in Figure 4, in 5 to 10-year-olds, almost twice as many boys as girls have a mental disorder and in 17 to 19-year-olds the reverse is true. In fact, more than twice as many girls as boys disclose a mental disorder in the 17–19 age group.

Can you think of any reasons why this might be the case? Jot down a few notes to yourself for future reference.

Discussion

You may have thought about differences in the ways boys and girls develop physically and mentally over childhood and adolescence, and that the social pressures on girls may be more intense than for boys as they get older. Perhaps you can think of some young people you know with mental health issues that you have personal theories about.

During the course, you will unpack the knowledge underlying these figures and explore what is happening both physically and socially during adolescence that might help us to understand these differences. Before that, it’s worth going ‘back to basics’ to consider what ‘mental health’ actually is.

2 What do we mean by ‘health’ and ‘mental health’?

Can you be healthy without good mental health? Ever since 1946, the World Health Organization’s original definition of health has been upheld:

‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’.

You’ll see that it takes a very wide view of health that includes the mental and social. Certainly, if your mental health were poor you would feel unwell, or at least lack a sense of wellbeing. Many healthcare professionals and researchers argue, however, that the perfect state of health and wellbeing described above is unattainable. Taking this argument further, perhaps it is even harmful for our mental health to suggest that we should somehow aim for this unachievable goal.

Physical and mental health are interdependent, so for example, people who are living with a long-term chronic health condition such as type 1 diabetes or cystic fibrosis may experience challenges to their mental health. Conversely, people who are experiencing mental illness may take less care of their physical health or engage in behaviours that exacerbate their mental health difficulties. Either way, individuals who are unwell will experience a combination of symptoms and challenges that are likely to be physical, mental and social.

2.1 The impact of mental health

As previously indicated a mental health problem can show itself in different ways and usually interferes with some aspect of everyday living. The Mental Health Foundation says:

Good mental health is characterised by a person’s ability to fulfil a number of key functions and activities, including:

- the ability to learn

- the ability to feel, express and manage a range of positive and negative emotions

- the ability to form and maintain good relationships with others

- the ability to cope with and manage change and uncertainty.

Now work your way through Activity 4.

Activity 4: The impact of mental health problems

a.

The ability to learn

b.

The ability to feel, express and manage a range of positive and negative emotions

c.

The ability to form and maintain good relationships with others

d.

The ability to cope with and manage change and uncertainty

The correct answers are a, b, c and d.

Discussion

Did you tick one or more of them? It is important to note that a person who is struggling in any of these areas does not necessarily have a mental health problem. These kinds of difficulty are warning signs though, and you will find out more about warning signs in Session 2.

3 How has the concept of mental health evolved?

The history of ideas about mental health is not, as many people expect, a straightforward journey of progression where things steadily improve, and we understand more about how to treat mental illness. Ideas about the nature, causes and best ways of treating or responding to mental health problems have changed significantly over time, influenced by a variety of factors, including the social and cultural context.

Activity 5: What causes mental health problems in adolescence?

Now, go to the poll and select a possible cause that is closest to the one you have written.

Discussion

A review of research worldwide conducted after 2010 (Choudhry, 2016) found that people’s beliefs about the causes of mental health problems fell into three broad categories:

- Stress from social pressures and life events

- Supernatural and spiritual reasons

- Biomedical, including genetics (anything to do with how the body works)

The media have popularised the idea of young people being ‘snowflakes’, dubbed ‘emotionally weak and lacking resilience’ although academic Shelley Haslam-Ormerod (2019) claims this is unfair and insulting ‘because it encourages stigma and evokes hatred’.

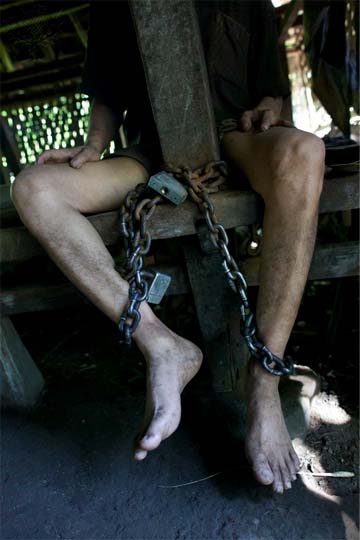

Before the 20th century, people commonly believed that mental illness was caused by supernatural forces. Correspondingly, treatment, often involving physical restraint, was based on religious or superstitious reasoning (Jutras, 2017). Since then, debates about the role of biological versus psychological factors in causing mental illness have dominated, as you will see next.

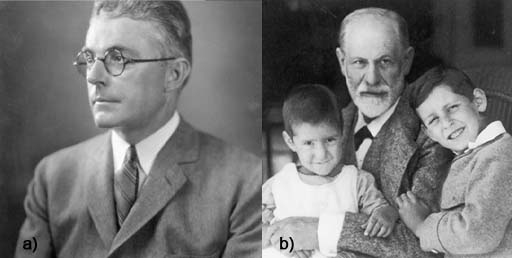

In the psychology camp, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) pioneered psychodynamics, a theory about how the mind works based on the idea that mental illness resulted from unresolved unconscious issues arising in childhood. Treatment involved encouraging the patient to talk about past events.

By contrast, the behaviourist viewpoint (initiated by John Watson (1878–1958)) assumed that people became ‘conditioned’ to display certain maladaptive behaviours. The proposed solution was further conditioning by applying rewards and punishments to encourage the desired behaviour, partly supported by the well-known dog experiments conducted by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936). In these experiments it was discovered that the dogs could be ‘conditioned’ to salivate even when food was not present by other stimuli that were associated with the food such as the ringing of a bell.

The modern bio-medical perspective views mental health problems from an illness perspective, identifying inherited genes, hormonal changes and alterations in how the brain works as underlying a range of ‘mental illnesses’. Treatment involves medicines that act on the way the brain works, as well as lifestyle advice based on knowledge of the links between brain health and body health. Immense efforts continue in research laboratories to understand and treat the possible biological foundations of mental health problems. Modern psychological perspectives assume that people can be supported to think differently about challenges to their mental health and learn to manage them with or without the support of medicines.

You will learn more about the modern approaches in sessions 4 and 8, but next, you consider some of the cultural aspects of mental health.

3.1 Identity, language and stigma

Having a mental health problem, and the language used to describe it, can have a profound impact on how a person sees themselves: their sense of identity. This point was reinforced by Ron Coleman:

In the early 1980s I was diagnosed as schizophrenic. By 1990, that was changed to chronic schizophrenic and in 1993 I gave up being a schizophrenic and decided to be Ron Coleman. Giving up being a schizophrenic is not an easy thing to do for it means taking back responsibility for yourself, it means you can no longer blame your illness for your actions. It means there is no disease to hide behind, no more running back to hospital every time things get a bit rough, but more important than any of these things it means that you stop being a victim of your experience and start being the owner of your experience.

Social perspectives used to understand mental health tend to be wary of attaching labels to people. To some extent, there is a view that everyone has at least some problems with their mental health at some point in their life. Under the social approach, factors such as poverty, unemployment, inequalities, oppression, divorce and living in a deprived area are seen to lead to ‘stress’ and ‘distress’, which are reactions to difficult circumstances rather than being illnesses (U’ren, 2011; Smail, 2005).

However you think about the characteristics of mental health problems, in cultures around the world it can be difficult to shake off the stigma that surrounds it.

The idea of stigma was first described by the American social psychologist Erving Goffman (1963), as the cause of a ‘spoiled identity’. Here Goffman is describing how individuals are often seen as different in some way, by virtue of how they look, act or behave and the impact that this can have upon how they feel and value themselves. Research exploring stigma includes careful analysis of groups of individuals who are excluded, rejected, blamed and devalued in some way (Scrambler, 2009).

In the next activity, you’ll watch a video of some young people talking about their experience of mental health stigma.

Activity 6: Stigma

Watch the video of a group of young people talking about their mental health and when they first started experiencing difficulties during adolescence. How do the young people describe the stigma they have experienced? Stop and start the video as much as you like.

Write down a list of bullet points which reflect the stigmatising experiences these young people describe. You can write these as a list of words or phrases.

Transcript: Video 2: Mental health in our own words

Discussion

Your notes might have gone something like this, although there are several ways you might have interpreted these brief accounts.

Feeling alone.

Feeling like people don’t really understand you.

Feeling isolated.

Wanting to be treated as a ‘normal’ person.

People not realising you are ill or that you are unwell.

People expecting you to look and act in certain ways because of your mental health.

Being called names like ‘schitzo’.

Name calling, feeling alone, singled out and devalued in some way are just some of the ways in which these young people talk about their experiences of being viewed as different and the stigma related to their mental health difficulties.

Social scientists spend a lot of time interpreting accounts of people’s experiences. Gathering a range of personal experiences can help to build and test theories. Here, you have been applying theory – a definition of stigma – to some real-life accounts.

3.2 #oktosay

Stigma poses a significant obstacle to tackling mental health, partly because it makes people reluctant to talk about their problems. Encouraging people to open up about their problems is now the focus of many high profile media campaigns. Many celebrities, including the UK royal family, are spearheading initiatives such as ‘#oktosay’ in social media to get people to talk about their mental health. In the next video, you’ll see the musician Stormzy talking about his mental health.

Activity 7: Talking about mental health

Watch the interview with Stormzy below and consider what effect it has on you. Does it make you feel more likely to talk about mental health?

Transcript: Video 3: Interview with Stormzy

As you watch, think too about the relationships between mental health and

- access to opportunities to talk

- support networks

- trying to appear strong and able to cope.

Discussion

You may feel a certain degree of empathy for Stormzy who talks about his experiences of depression which were compounded by the pressures he felt to appear strong and able to cope with the new challenges that accompanied his musical career.

As you work through this course, you’ll learn more about how people can be supported to talk about their problems and therefore understand the issues better.

Talking about mental health can often be demanding because people may not have the words they need at their fingertips. One gets the sense that Stormzy has become more comfortable in sharing his experiences through his music and using his experiences to encourage others to talk.

As you saw earlier, language can be hurtful and affect a person’s sense of identity. Language plays a big part in shaping people’s experiences. Language is also shaped by certain cultural perspectives. As a result, what different people mean by the words they use may differ, as Johnstone, a clinical psychologist, argued:

How quiet do you have to be before you can be called withdrawn? How angry is aggressive? How sudden is impulsive? How unusual is delusional? How excited is manic? How miserable is depressed? The answers to all these questions are to be found not in some special measuring skill imparted during psychiatric training, but in the psychiatrists’ and lay people’s shared beliefs about how ‘normal’ people should behave.

This takes you to a short introduction to mental health policy.

4 Mental health policy

The UK government, along with many others around the world, accepts that childhood experiences can have a ‘lasting impact’ on mental health through to adulthood, and that more needs to be done to support children and young people who are experiencing mental health problems (CQC, 2017). The figures you looked at in the first section relating to the apparent rise of mental disorders in young people are concerning, but they only recognise children and young people who have been diagnosed with a ‘mental disorder’. The problem is wider than these statistics, however, because there are many more families who are concerned about the mental health of their young people and many young people choose not to disclose or share their experiences. They aren’t reflected in the statistics because they may never have sought help or perhaps do not want to admit their concerns. Ideally, the aim would be to intervene sufficiently early to prevent, as far as possible, mental disorders from developing.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) in the UK recognises that for too long people have had to fit in around a fragmented system rather than accessing services designed around their needs. Designing services around individual needs is commonly referred to as person-centred care. As well as becoming centred on the needs of children and young people, services need much better coordination so that it is clear what is available and how to access it. In 2018, the CQC recommended:

- joint action across government to make children and young people’s mental health a national priority

- a clear ‘local offer’ of the care and support available to children and young people

- that everyone who works, volunteers or cares for children and young people should be trained to encourage good mental health and offer basic mental health support

- inspectors should look at what schools are doing to support children and young people’s mental health (adapted from CQC 2019)

These grand aims would result in huge benefits for adolescent mental health. There is a clear element of prevention here too, in the ambition to train people to ‘encourage good mental health’ and offer basic support. Restricted availability of public resources, however, poses a significant difficulty in delivering these recommendations. Not only is it costly to train families, staff and volunteers to staff services adequately, but changing practices also requires a change in culture, which depends on good leadership. Some of the necessary leadership comes from charities, and the charity MIND is actively pushing for change.

Activity 8: MIND

Visit the MIND website and pick out about three of the policy areas to explore. Scan each of the three or so pages you land on and jot down a short summary of the work MIND is doing.

MIND website (Remember to open this page in a new window or tab so you can refer to the course and make notes.)

Then, think about the impact of organisations such as MIND in influencing policy. How important do you think it is for an organisation like MIND to be actively engaged in putting forward a citizen’s viewpoint?

Discussion

Three examples here are:

- The page about ‘Mental Health Act Review’ shows how MIND ensured that patients’ perspectives were forefront in the review, by facilitating people to feed in directly to the process.

- The page about ‘Talking therapies’ explains how MIND are part of a coalition calling for the maintenance and development of talking therapies on the NHS.

- The page about ‘Our work in Parliament’ explains how MIND is making sure that MPs are well informed about mental health issues and briefs them on important factors in preparation for parliamentary debates.

Thinking about the role of charities such as MIND, it’s clear they act on behalf of people who need support and ensure that their needs and perspectives are kept high on the government agenda. It would be very difficult for individuals to lobby government in this way, and individual service providers may not see the whole picture of what people need.

There is considerable political momentum building for improving the mental health of young people. Much of the success will depend on everyone who has contact with young people, not least their parents and teachers, having the skills to support them appropriately.

5 This session’s quiz

Check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you’ve finished.

6 Summary of Session 1

The main learning points of this first session are:

- The percentage of adolescents experiencing mental health problems has risen steadily since 1999, as surveys carried out in England have shown. There are differences between boys and girls in the ages at which problems develop.

- Mental health comes under the umbrella of overall health, and cannot easily be separated from physical health. Mental health problems can interfere with a person’s daily activity and ability to function.

- Treatment of mental health problems has been based historically on a range of beliefs about what is causing the problem, from religion and superstition, to psychology and medical explanations. Although it is now widely accepted that one of the first solutions to preventing or supporting a mental health problem is to talk about it, stigma often prevents people opening up about their problems.

- The ambition of policymakers is to revolutionise mental health care and to make it designed around the needs of citizens and to help promote good mental health.

In the next session, you will explore adolescence. What is adolescence, and what is normal behaviour during this transitional stage of development? Some of the mysteries of the adolescent brain will be revealed, and you will come to understand that this is a special and important time in a person’s development.

Now move on to Session 2.

Glossary

- Adolescence

- Adolescence is a transitional stage of physical and psychological development that generally occurs during the period from puberty to adulthood. Adolescence is commonly associated with the teenage years.

- Behaviourist viewpoint

- Behaviourism describes a psychological approach to understanding human behaviour and other animals. It assumes that behaviour is either a reflex provoked by particular stimuli within the environment or as a consequence of that individual’s history, including their upbringing and learning within their environment.

- Bio-medical perspective

- Biomedicine and the biomedical approach is a branch of medical science that draws upon biology to explain and understand health and ill health.

- Psychological perspective

- Also termed the psychological model of mental illness focuses on how the mind works and the effect of this on a young person’s thoughts, feelings, and subsequent behaviour.

- Cystic fibrosis

- Cystic fibrosis is an inherited health condition that causes mucus to build up in the lungs and digestive system.

- Emotional disorders

- Describes the difficulties experienced with mood and emotions such as feelings of anxiety or depression.

- Mental disorders

- Mental disorders are generally characterised by a combination of abnormal thoughts, perceptions, emotions, behaviour and relationships with other people. Mental disorders are varied and include depression and anxiety as well as conditions such as schizophrenia, OCD and psychoses.

- OCD

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common mental health condition where a person has obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours.

- Psychodynamics

- Describes an approach to psychology that emphasises systematic study of the psychological forces that underlie human behaviour, feelings, and emotions and how they might relate to early experience.

- Social perspective

- Also termed the social model of mental illness focuses on the social environment and the roles people play and views mental illness as being a consequence of how young people are viewed and treated in society, rather than determined by biology.

- Stigma

- Stigma is a term used to describe the disapproval of, or discrimination against, an individual or group of individuals based on their appearance or behaviour that distinguishes them from other members of a society.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Victoria Cooper, Sharon Mallon and Anthea Wilson and was published 21 December 2021. We would also to thank Jennifer Colloby, Steven Harrison and Karen Horsley for their key contributions and critical reading of this course. We would like to thank the parents, young people and professionals who shared their experiences with us.Their willingness to share sensitive and highly personal accounts of having or supporting those with mental health challenges adds greatly to this course and we will hope will benefit all those who find themselves in similar situation.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below (and within the course) is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Session 1: ‘A crisis in context’

Figures

Figure 1: AJ PHOTO/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Figure 3: adapted from Copyright © 2018 Health and Social Care Information Centre. Open government Licence http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/ open-government-licence/ version/ 3/

Figure 4: Copyright © 2018 Health and Social Care Information Centre https://files.digital.nhs.uk/ A0/ 273EE3/ MHCYP%202017%20Trends%20Characteristics.pdf http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/ open-government-licence/ version/ 3/

Figure 5: By woocat/Shutterstock.com

Figure 6: Top: Left: Zayn Malik: Jared Milgrim/Alamy Images; middle Jesy Nelson: Featureflash Photo Agency/shutterstock.com; right Billie Eilish DFree/Shutterstock.com; Bottom: Left: Marcus Rashford: Vlad1988/Shutterstock.com; middle: Emma Raducanu: Roger Parker/Alamy Stock Photo; right: Zoe Sugg: Anton_Ivanov/Shutterstock.com.

Figure 7: (a) Prakruthi Prasad https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/ File:John-B-Watson.jpg; (b) Mary Evans Picture Library/SIGMUND FREUD COPYRIGHTS

Figure 8: Will & Deni McIntyre/Photo Researchers/Universal Images Group

Figure 9: Paula Bronstein/Getty Images News/Getty Images/Universal Images Group

Audio/Video

Video 2: In our own words: courtesy: Courtesy: Mind https://www.mind.org.uk/ https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=_y97VF5UJcc

Video 3: clip of Stormzy talking about depression on C4: Getty Images

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – The Open University.