Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 2:42 PM

Session 4: Recognising mental health problems

Introduction

As indicated in session 1, the way in which we talk about mental health varies from person to person. In general, particularly when it has a major impact on their ability to function, a person who is feeling ‘extremely sad’ or ‘very worried’ may be diagnosed with a mental health condition, for example, ‘depression’ or ‘anxiety’. However, in other cases, such feelings may be viewed as understandable reactions to events that will pass with time. A person who seeks to make sense of their mental health problems may come to understand it in the context of their life experience, while a health professional may be looking for evidence of specific ‘symptoms’ to see if a psychiatric diagnosis is appropriate.

Behind the scenes, some mental health practitioners are continually seeking the right balance between making mental health a medical problem, or seeing it as a continuum along a line of ‘healthy’ to ‘unhealthy’ adaptations to life’s stresses. In this session, you will explore the different ways in which mental health is viewed.

To get started, listen to Tanya Byron again, this time talking about different professional approaches to recognising mental health problems. She uses a number of technical terms, but don’t worry too much about this now, as you’ll explore these in Activity 1.

Transcript: Audio 1: Interview with Professor Tanya Byron

Learning outcomes

By the end of the session, you should be able to:

recognise the range of professionals who are able to help an adolescent with mental health problems

outline the perspectives that professionals draw on to diagnose a mental health problem

explain the role of social media in shaping perceptions of mental health

debunk some common misconceptions about mental health.

1 Diagnosis and sense-making

The causes of mental illness are disputed, complex and are underpinned by differing theoretical perspectives – which are also referred to as models.

What this means is that there are different types of explanation:

| A social perspective | focuses on the environment and the different roles that people play. It also considers adverse experiences, negative life events and childhood adversity, such as exposure to violent behaviour, poverty, abuse, bereavement, parental divorce or separation, parental illnesses and/or non-supportive school or family environments |

| A psychological perspective | emphasises the role of thought and emotional processes and individual cognitive development in how a person will interpret their negative life events and how this may possibly affect their behaviour |

| A biomedical perspective | looks at brain structure and function, and is likely to see mental health problems/illnesses in relation to how the brain works and is influenced by hormones and an individual’s genes, with other issues merely operating as triggers |

In reality, none of these three perspectives alone can provide all the answers to what causes mental health problems in adolescence. They are often combined in what is called a bio-psycho-social model which recognises the importance of considering biological, social and psychological factors when attempting to understand and treat a young person’s mental health. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) is a government run organisation whose guidelines suggest that when healthcare professionals are assessing children and young people, they should routinely record social, educational and family situations. This includes the quality of interpersonal relationships (both between the person and other family members and with their friends and peers), thus acknowledging that family issues need to be taken into consideration.

Next, you’ll return to Tanya Byron’s interview offering her perspective on assessing a young person’s mental health as a clinical psychologist. In the activity, you’ll ‘unpack’ the extract of Tanya Byron’s interview with Professor John Oates.

Activity 1: Unpacking the terminology

Step 1: Below is the transcript for the interview extract. Read through it and hover over the highlighted technical words to access the glossary definition for each.

Tanya Byron: Well in a sense when I’m working with my colleagues, when I’m working with my teams, and we are assessing a young person, we tend to think in sort of blocks of theory, and in a sense through careful assessment, both qualitative assessment with the young person, with their family, often with schools and teachers. And sometimes with their friends. I mean if the young person, for example, is very depressed, or unable to communicate, friends are often a very useful resource of information. We are literally sort of kicking down different hypotheses that we may have about why this young person is presenting in crisis. So, to begin with we might wonder whether there are some neuro-developmental issues, is there something actually at a brain level that is making life increasingly challenging through this complex time? We obviously want to know what is going on at home, is there a specific amount of stress, risk factors, whether it is abuse or domestic violence, or just discord, marital breakdown and discord in the home that is contributing to this young person’s difficulties. Some young people may show very context-specific difficulties. So if I’m meeting young people where they are generally doing okay, but struggle really specifically at school, and are getting a lot of negative feedback, beginning to feel like they have failed, maybe becoming the person that they are being told they are, so it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, they stop thinking, they stop learning, they misbehave. We might then want to explore specific learning difficulties, you know, finding young people with very good IQs, but actually with learning difficulties, whether they are to do with sensory integration, or to do with dyslexia, or dyspraxia. Whatever we are looking at, it would help us explain why this young person, understandably struggles in that particular learning context.

John Oates: So that sounds pretty wide in the sorts of theoretical orientations you are drawing on, but are there specific therapeutic approaches that you take, or would you say you really have to match that to the case?

Tanya Byron: We do have to match therapeutic approaches to the case, which is why the most effective way of working with a young person, because of the system that they bring with them, is within a multi-disciplinary team. So, even though I would lead the team, I would rely on the expertise of my colleagues, who come from different skillsets, to be able to contribute to the assessment. And then sometimes themselves do further specific assessment, for example educational assessment, or neuro-developmental assessment. Sometimes you know much more sort of specific – we might have to scan some young people’s brains, erm, or even more psychotherapeutic colleagues, who might want to work with families and understand the family narrative. So it is quite complex, and in a sense as a consultant my role is to sort of navigate that, and to … what we do as clinical psychologists is we create what we call a formulation. In a sense we are creating an evidence-based narrative to the presenting difficulties. And actually just explaining to a young person, and their family what we think might be behind what is going on for them can be a very empowering experience, because once you understand a problem, to some degree you are almost in a much better position to try and solve it. So, yes, it is about navigating the complexities, sticking with an evidence-based model, and evidence based therapeutic approaches. And always working collaboratively with the young person, because obviously they need to be very much central to the treatment, they need to take ownership of it. It is their life, and so they also need to inform us and help us understand where we might not be quite hitting it in the right place for them. Communication is vital really.

Discussion

Professionals who work in a particular field of practice develop a specific vocabulary that can sometimes make communication difficult between people with different types of life experience or expertise. It is important not to feel intimidated when faced with specialist language you are not familiar with, and perfectly acceptable to ask for further explanation in a conversation with a specialist. Professor John Oates is a specialist academic and would have been familiar with the language. You are provided with a glossary here but in other circumstances, a good dictionary is invaluable, especially if you are sent a letter or read something that is full of terms you don’t understand! It is also important to note that healthcare professionals base their practice on the best evidence. By contrast, the ‘myths’ perpetuated on social media and in everyday life are based on very little evidence.

a.

Social

b.

Psychological

c.

Biomedical

The correct answer is a.

Discussion

Tanya is predominantly talking about a social perspective here.

1.1 The case of George

Various people can become involved in trying to make sense of any particular individual’s mental health problems, including:

- the mentally distressed adolescent themselves

- their friends, family members and others who interact with them socially

- mental health and other professionals who have developed and use various theories, therapies and forms of treatment and support to explain and respond to an adolescent’s mental health problems.

In practice, all these different parties will have a view on what is happening and why, and what ought to happen next when an adolescent is (or appears to be) distressed. In some cases, these different views can contribute to a range of support options that complement each other. On the other hand, there can be times when these different views can lead to contradictory ideas about what the young person needs. For instance, does someone who is feeling anxious much of the time need counselling or medication? Or do they need help to change a situation at school or at home, which might be causing their anxiety? In the next activity, you’ll consider the case of George.

Activity 2: Understanding George

a.

A brain abnormality

b.

Adolescent brain development making George more emotionally sensitive

c.

No sense of belonging to a peer group

d.

Family break-up

e.

He doesn’t like Mum’s new partner

f.

Liz’s history of depression

g.

He’s jealous of his sister

h.

He is naturally reserved

i.

A cascade of issues arising from poor sleep

j.

Issues at school

k.

Friendship issues

The correct answers are a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j and k.

Discussion

To an extent, it is sensible to not rule out anything from the list if you wanted to work out how to help George. You may have wondered what would constitute a ‘brain abnormality’, given that scientists are still working out what is normal in adolescence, and that people exist on a diverse spectrum of personalities and capabilities. Medical treatment with antidepressants is an attempt to adjust the chemical balance at brain synapses to improve mood, assuming that there is an abnormality to correct. As you found in Session 2, adolescence is a time of greater emotional sensitivity, so this could partly explain George’s situation. And you’ll see in Session 6 how important sleep is for young people. There are several social reasons why George might be unable to cope, especially if he does not have a strong network of friends. Issues at home and disruption of family relationships can also contribute. His mother’s depression could indicate an inherited tendency to depression.

Theoretical models can help to organise thinking around what can seem a very complex picture, as you’ll see next.

1.2 Determinants of health

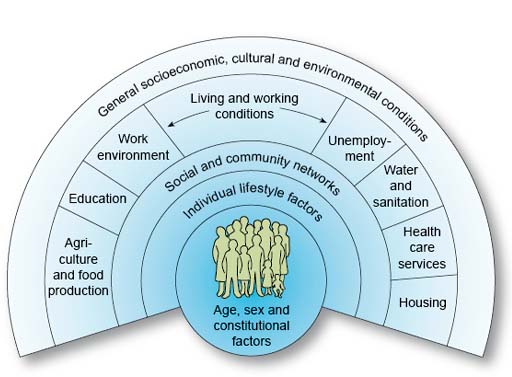

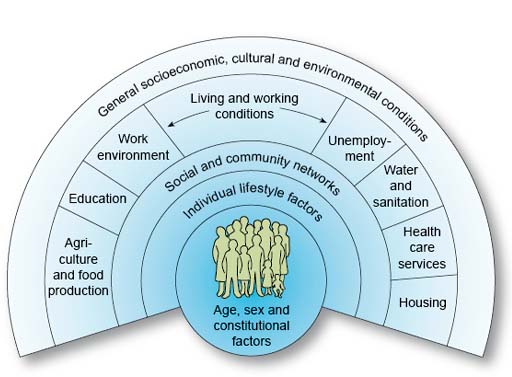

A young person’s social context can bring a wide range of factors to bear on their health and wellbeing. One of the most useful models for representing these factors is this one by Dahlgren and Whitehead (1993; cited in Dahlgren and Whitehead, 2007) in the figure below.

Dahlgren and Whitehead’s model has been widely used by academics and practitioners to guide their thinking about health.

Dahlgren and Whitehead’s model depict layers of influence on health. This model maps the relationship between the individual, their environment and health. Individuals are at the centre. Surrounding them are influences on health that can be modified. The first layer represents individual behaviour and lifestyle that can potentially enhance or damage health, for example the choice to smoke or not. The next layer refers to wider social and community influences, which can either provide mutual support or lack of support. The third layer represents structural factors, including housing, working conditions, access to services and provision of essential facilities.

The ‘age, sex and constitutional factors’ in this model apply to both the biomedical and the psychological perspectives, although each will focus on different ‘constitutional factors’. Individual lifestyle factors are also critical to the biomedical and psychological perspectives since diet, exercise and sleep, for example, can directly affect mental health, and mental health can affect lifestyle.

Activity 3: George’s social determinants

Study the diagram in Figure 3 and think for a moment about how they might apply to George.

Discussion

The wider range of factors related to the community and the person’s wider social, cultural and economic environment primarily make up the social determinants of health. In George’s case, many of the social factors, including his family situation, would fit in to the ‘social and community networks’ part of the model. If you were helping George, you might also consider what is happening in his education setting and whether the healthcare services were able to respond to his needs. Considering the socioeconomic conditions, if George lived in a relatively deprived community he would be more at risk of ill health than if he lived in a relatively affluent community (Marmot et al., 2020). Unfortunately, it is unlikely that an individual practitioner can change a young person’s socioeconomic circumstances.

A variety of professionals draw, to varying degrees, on this wide range of factors to make sense of a young person’s mental health. You’ll learn more about this next.

2 Professional approaches

There can be a surprising range of professions and practitioners involved in helping young people with mental health problems. The next activity will get you thinking about what you already know.

Listen to this interview of a parent talking about their child’s mental health and the different professionals that can provide a supporting role.

Transcript: Audio 2: Providing a supportive role.

Activity 4: A range of professions

How many types of practitioner (or professions) work in the mental health field? Have a look at the list here and tick one that you feel most confident about. This is a polling tool, which will feed your inputs into a larger picture of all the learners engaged in this course.

Reflect on the following: which was the first type of practitioner or profession that came to mind, and why do you think they were the first one that you thought of?

Discussion

Your response to this activity will depend very much on your own experiences. Did anything surprise you in the poll results? How did your responses compare to those of your fellow learners?

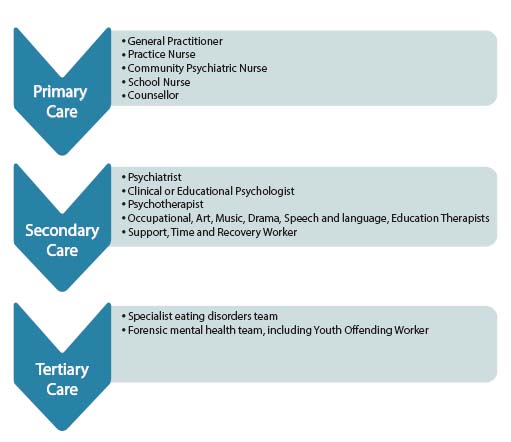

Have a look at Figure 5 below for a summary of the professions and teams that can be involved.

Primary care is usually the first point of contact for people when they become unwell, for instance, when they experience symptoms that are of concern to themselves or others. Primary care is also usually the ‘gateway’ to receiving more specialised care.

Secondary care is for someone who has received primary care and is referred to the next level of care. These services are usually consultant-led (with a psychiatrist as the clinical lead) and include mainstream out-patient services like Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), as well as in-patient psychiatric units.

Tertiary care is for someone who requires a highly specialised team of professionals. This may involve someone being treated by an eating disorders team (e.g. in an in-patient unit for people with severe eating disorders) or in a forensic mental health facility (i.e. in a facility treating offenders who have severe and enduring mental health problems). You will recall a parent describing the route through which her daughter was able to receive the support she needed for her mental health in Audio 2. This included a GP consultation followed by therapeutic counselling.

2.1 Comparing medical approaches

Psychiatry is a branch of medicine that deals with mental health. Doctors such as general practitioners and psychiatrists draw on models of illness to assess a patient and provide a diagnosis. The biomedical model forms the basis of modern medical practice, although there are few doctors nowadays who would not also draw on social and psychological explanations of mental ill health.

Biomedicine explains health in relation to biology. It attaches importance to learning about body structure (anatomy) and systems (physiology) and understanding mechanisms like the circulation of blood, hormone functions and the workings of the brain. This view offers a particular and distinctive way of ‘seeing’ and understanding health in relation to the body. Certain tests establish what is wrong and medicines are given as a cure or to alleviate symptoms, or surgery repairs or replaces defective body parts.

The biomedical model tends to focus attention on the individual, not groups of people or the health of society more generally. Under this model, health services are geared mainly towards sick people and high value is placed on specialised medical services. Doctors and other qualified experts act as gatekeepers to services. The main function of a health service is remedial or curative, aimed at getting people back to productive lives.

In the next activity you’ll consider two contrasting medical approaches.

Activity 5: Different viewpoints

Symptoms may overlap between diagnoses or may not meet the criteria for a particular ‘disorder’, but still require treatment. You may have noticed that George’s GP thought he had a combination of anxiety and depression. Taking these issues as well as the views of patient groups into consideration, there has been a move over recent years, and particularly within the UK, towards a more tailored approach to diagnosis and management of mental health that takes the lead from and actively involves the patient (Gask et al., 2009).

With the emergence of biological psychiatry and modern advances in brain and behavioural sciences, most mental illnesses are increasingly presumed to have a neurobiological basis, even if that basis is, as yet, poorly understood.

2.2 Potential sources of conflict

Multidisciplinary teams, which comprise a range of different professions, can be effective because they combine a range of skills and perspectives to help a young person. Although they aim to work together for the benefit of the young person they are helping, there can potentially be conflict between professions, partly because they might be taking different perspectives on diagnosis and treatment. Family members may also feel in conflict with healthcare professionals if they have strong personal views on the use of medication or talking therapies, or labelling their children with a stigmatising diagnosis.

Clinical Psychologist Lucy Johnstone argues that a medical diagnosis ‘turns “people with problems” into “patients with illnesses”’ and that this can be damaging because the medical meaning essentially displaces the person’s own understanding of their situation and their sense of self (Johnstone, 2018, p. 31). Moreover, she continues, psychiatric diagnoses commonly lead to a sense of stigma and shame ‘by locating the difficulties within the person’ (p. 35) rather than their social environment and life story.

The psychologist’s alternative to a medical diagnosis lies in the ‘psychological formulation’. According to Johnstone (2018, p. 39), ‘it is the difference between the message “you have a medical illness with primarily biological causes” and “your problems are an understandable emotional response to your life circumstances.”’ In creating a psychological formulation, the service user and the practitioner combine their knowledge and skills and together reach a ‘best guess’, or hypothesis, about the roots of the problem and agree a way to move forward.

The next activity will allow you to compare and contrast the perspectives of a psychiatrist and a clinical psychologist as they explain their professional allegiances and discuss how they would help a young woman called Mandy.

Activity 6: A psychiatrist and a psychologist

Watch the two videos of a psychiatrist Dr Elizabeth Venables and a psychologist Dr Marion Bates talking about their work. What are the similarities and differences? Can you identify any potential source of conflict?

Transcript: Video 2: Dr Elizabeth Venables

Transcript: Video 3: Dr Marian Bates

| Similarities | |

| Differences |

Discussion

Comparing and contrasting are useful analytical skills that are commonly used in academic and professional life.

| Similarities | They both have to be registered with a professional body or council. They are both interested in finding out about the person’s life story and the therapeutic benefits of talking. Both recognise the biological, psychological and social aspects of mental health. |

| Differences | The psychiatrist is medically trained and can prescribe medication and in fact medication appears to be central to her work. By contrast, the psychologist does not prescribe medication. The psychiatrist aims to arrive at a diagnosis, whereas the psychologist avoids making a diagnosis and works with the client’s own language for describing and understanding their problem. There seemed to be the potential for conflict over whether or not a diagnosis was needed. |

Next, you’ll consider the role of social media in shaping perceptions of mental health.

3 The role of social media

Social media is a big part of the lives of many of us now, but social media has become a part of a young person’s social world to an extent that was unthought of when Dahgren and Whitehead created their model (introduced in Section 1.2) containing the social determinants of health.

The reference to ‘Communites’ mentioned in the diagram would now extend to media ‘friends’ and ‘followers’ as well as online discussion forums.

Research continues to explore the impact of social media on mental health. While social media is often discussed in negative terms, the relationship young people have with social media is quite complex. In the next activity you will listen to an interview where two young people, Martha and Josie reflect on their own social media use and discuss its impacts.

3.1 Young people and social media

Listen to the following interview with Martha and Josie talking about the impact of social media and ideas of perfection.

Activity 7: Ideas of perfection

What are the key messages presented here? Write down a few bullet points.

Transcript: Audio 3: Ideas of perfection

Discussion

Martha and Josie discuss how social media has the capacity to present unrealistic ideas about people’s lives and to perhaps encourage other young people to adhere to ideas of perfection. They both criticise the impact that social media influencers can have upon young people in presenting only the positive highlights and an image of their life which isn’t necessary real or healthy.

Unlike local communities, social media contacts can be invisible to parents and other caregivers and it can be difficult to know anything about what a young person is seeing and with whom they are interacting. This can be a source of concern for many parents.

Social media can, however, become a source of support for many young people who are struggling with their mental health, and this will be discussed in Session 7. In the next section, you’ll focus on the role online communities can play in shaping the way people regard their mental health, sometimes in a harmful and unhealthy way.

3.2 Images of perfection?

Young people can spend a great deal of time engaging with social media in very different ways. From social media platforms, messaging and communication applications, online television or radio and online games, young people share images, communicate, learn and play using these different media.

Activity 8: Body shaming

Watch Video 4 of a young person Chessie King who is a YouTuber interested in online digital media and particularly body images. As you watch, make notes which address the following questions:

- How are young people influenced by the reactions of others via social media?

- How might cyber bullying impact upon a young person’s mental health?

Transcript: Video 4: Cybersmile and Chessie King Body Positivity Campaign

Discussion

This video highlights the many pressures that social media can exert and here it is presented in relation to body image and the pressure to look a certain way. Many young people experience body shaming and report being the victims of online trolling.

Online trolling is a name used to describe persistent and often seemingly random comments made in an online community to provoke emotion and reaction. Research indicates how online trolls often intend to seek attention by causing upset and distress in others, whilst hiding behind their screens.

4 Common misconceptions about adolescent mental health

In the general population, views about what mental health problems are and what causes them are likely to have come from personal experiences or ‘common sense’ understandings picked up from other people or the media. Such views may not be particularly influenced by academic research and writing, nor are they necessarily informed by professional interests in the topic.

Activity 9: Reflecting on common misconceptions

Read through the misconceptions about mental health below and then reflect on this.

Reflect on the issues raised above.

- What are your own thoughts and views on some of the information and misinformation disseminated in the media?

Discussion

It’s more than a simple matter of awareness or of public perception. Different perspectives and insight gained through personal as well as professional experiences are important to understanding mental illness, and those who are affected by, and living with mental health conditions. The way we perceive an issue, in what light we view a particular topic, greatly influences our thoughts and behaviours, and how we relate to, understand or come to terms with our own and other people’s experiences. We can see things from positive, negative or neutral viewpoints. Mental ill health is clearly an emotive, deeply personal and sensitive discussion area. A better understanding of the issues, the scientific and clinical backdrop to headline news, a closer examination of the evidence (which is often controversial), and informed debates around key issues, will help to dispel misconceptions and misunderstanding, and eliminate stigma.

5 This session’s quiz

Now it’s time to complete the Session 4 badge quiz. It is similar to previous quizzes, but this time instead of answering five questions there will be fifteen.

Session 4 compulsory badge quiz

Remember, this quiz counts towards your badge. If you’re not successful the first time, you can attempt the quiz again in 24 hours.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window then come back here when you’ve finished.

6 Summary of Session 4

The main learning points of this session are:

Social, psychological and biomedical perspectives can help practitioners to make sense of mental health problems. Determinants of mental health extend from aspects of the person that cannot be changed through to their behaviours, social networks, and wider characteristics of the communities where they live.

Professionals who work in the mental health field can take contrasting approaches to their work, and this can create the potential for conflict. Mostly, however, they are keen to combine their skills productively to help the young person.

Social media form a significant aspect of the friendship networks and wider communities for many young people. Social media can sometimes distort how young people view themselves through contagion and social comparisons using images and misinformation.

You are now halfway through the course.

Now to go Session 5.

Glossary

- Antidepressants

- Medication prescribed by a medical practitioner. Often used to treat depression and anxiety.

- Behavioural sciences

- Behavioural sciences explore how animals and humans think and behave. It involves the systematic analysis and investigation of human and animal behaviour through observation and controlled scientific experimentation.

- Biological psychiatry

- Biological psychiatry is an approach to psychiatry that seeks to understand mental illness in terms of the biological function of the nervous system.

- Biomedicine

- Biomedicine is a branch of medical science that draws upon biology to explain and understand health and ill health.

- Dyslexia

- A common learning difficulty that can cause problems with reading, writing and spelling.

- Dyspraxia

- A developmental disorder of the brain in childhood causing difficulty in activities requiring coordination and movement.

- Evidence-based model

- A model based on evidence.

- Evidence-based narrative

- Defined as stories with an identifiable beginning, middle, and end that provide information about circumstances, individuals, and conflict; raise unanswered questions or unresolved conflict; and provide solutions. They provide a way of communicating clinical assessments.

- Formulation

- A particular expression of an idea, thought, or theory.

- Hypotheses

- A supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation.

- IQ

- An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence.

- Learning difficulties

- A difficulty with learning. Examples might include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dyspraxia and autism for instance.

- Multi-disciplinary team

- Professionals and practitioners form a number of different disciplines such as health, psychology and social care for instance.

- Neuro-developmental

- Development of the nervous system, including the brain and neurological responses.

- Psychotherapeutic colleagues

- Psychotherapy is a type of therapeutic approach used by psychologists.

- Qualitative

- Relating to the measurement of something based on its qualities rather than its quantity. In psychological research terms, qualitative assessment relies on unstructured and non-numerical data such as those derived through observations, field notes and interviews.

- Sensory integration

- How our brain receives and processes sensory information so that we can do the things we need to do in our everyday life.

- Theory

- A supposition or a system of ideas intended to explain something.

- Therapeutic approaches

- Therapeutic approaches refer to the different approaches taken by psychologists for example in treating particular conditions.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Victoria Cooper, Sharon Mallon and Anthea Wilson and was published December 2021. We would also to thank Jennifer Colloby, Steven Harrison and Karen Horsley for their key contributions and critical reading of this course. We would like to thank the parents, young people and professionals who shared their experiences with us.Their willingness to share sensitive and highly personal accounts of having or supporting those with mental health challenges adds greatly to this course and we will hope will benefit all those who find themselves in similar situation.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below (and within the course) is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Session 4: Recognising mental health problems

Figures

Figure 1: Maria Iglovikova/Shutterstock.com

Figure 2: Olivier Le Moal/Shutterstock.com

Figure 3: adapted from the determinants of health (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1993; in Dahlgren and Whitehead, 2007)

Figure 4: wutzkohphoto/Shutterstock.com

Figure 5: ©The Open University – for full list only

Figure 6: De Agostini Picture Library\Universal Images Group

Figure 7: courtesy: artwork by ©Wilhelmina Peragine

Figure 8 and Figure 9 (interactive) ©The Open University

Audio/Video

Video 1: Mental health in children and young people, Dr Su Sukumaran courtesy The London Psychiatry Centre http://www.psychiatrycentre.co.uk/

Video 4: courtesy: 'The Cybersmile Foundation' https://www.cybersmile.orghttps://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=Csxszvx3oX8

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – The Open University.