Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 2:42 PM

Session 6: Supporting young people

Introduction

Supporting young people who are experiencing mental health issues can be challenging for both parents and practitioners. In this session, you will learn about some of the strategies that could make a real difference to any young person you are concerned about. You will draw on knowledge about what can help young people manage their mental health, as well as some insights gained from neuroscience.

To get started, watch this video in which young people who have experienced mental health problems discuss what has helped them.

Transcript: Video 1: Another Way: Young people talk mental health

Returning to the mental health spectrum introduced in Sessions 2 and 3, you might consider that in an ideal world everyone would be sailing along in the ‘healthy’ green zone, with perhaps the occasional dip into the yellow ‘coping’ zone when life becomes challenging. To think about interventions for mental health problems in a simplistic way, the aim is to help young people who are ‘struggling’ or ‘unwell’ to move to the ‘healthy’ or ‘coping’ end of the spectrum.

This session will begin by asking you to consider how you and others in your community can intervene and support a young person by listening actively and promoting helpful strategies.

Learning outcomes

By the end of the session, you should be able to:

explore ways of being a supportive influence to a young person experiencing mental health problems

improve your active listening skills in helping a young person

support a young person to manage their own mental health.

1 Parenting and supporting

Practitioners, researchers and policymakers globally are aware of the position of parents, and of other caregivers such as teachers, who often act as a ‘first responder’ to the mental health needs of adolescents.

When faced with a young person who is experiencing mental health problems, however, as a parent or practitioner it is easy to feel isolated and unsure of yourself and at times overwhelmed by the situation. You might at times worry that your efforts are having no impact or may be even doing more harm than good. It is important to acknowledge that anyone who works with or cares for a young person can potentially play an important role in identifying mental health problems at an early stage. Intervening early can help to improve the health and wellbeing of the young person, as well as those who care about him or her.

Activity 1: Parent and caregiver concerns

Step 1: Listen to an interview with a parent talking about their concerns about their child’s mental health and reflect on the different feelings and emotions that a parent might experience.

Transcript: Audio 1: Feeling helpless

Discussion

Parents and caregivers with a child who is experiencing difficulties with their mental health often report feeling helpless and at a loss as to know how to reach out and help their child, particularly as they may become withdrawn and appear disinclined to talk about things. Parents and caretakers may blame themselves for their child’s distress and feel a strong urge to try and ‘fix’ their problems for them. While this is quite a natural response, in this activity you will examine different ways of responding.

Step 2: Now read some of the concerns and frustrations parents and caregivers of young people often express regarding their attempts at supporting a young person. Take the role of a trusted friend and consider what you could say in response to each of these statements that would help to ease the concerns and frustrations. Once you have thought of what to say, click to reveal a comment.

I feel that I am responsible for solving their low mood.

Discussion

As a parent or ‘responsible adult’, it is easy to think you have to ‘fix’ things for young people. Although it is true you can play a key supportive role, your main aim will be to enable the young person to work things out for themselves as far as is possible and safe. This allows them to develop their life coping skills and will help them to develop for the future.

It’s hard to stay patient and calm when they don’t want to communicate.

Discussion

It’s very hard to remain calm and just be patient with your child when they ignore you or just refuse to talk things through but then talking about feelings can be really hard, especially when young. Giving your child some time to think things through but knowing that you are there for them and here to listen to them when they are ready to talk is so important.

They can’t seem to shake off the negative thoughts whatever I do or say.

Discussion

As parents or caregivers its tempting sometimes try and ‘fix’ our children’s problems. This is very a very natural response. Whilst it is so important to listen to your child, support them and be there for them, you cannot fix them. Effective support comes from providing a safe space for them to find their own ways of coping and managing how they feel.

I don’t want to hassle them with too many questions and become a source of annoyance.

Discussion

Just listen to your child when they come home from school or back from time spent with friends and perhaps have found something difficult or challenging in their day. Don’t interrupt and try and solve their difficulties – just listen. It’s hard but makes you appreciate how often it feels more about you as a parent or caregiver and how you feel in response to their difficulties. Often young people need to just articulate and move on. As parents and caregivers we want to solve, but often it’s more helpful to just listen.

What if they reject my advice and it pushes them away further?

Discussion

It’s important that young people develop self-reliance and the capacity to solve their own problems, where possible. Whilst this might not align with your own views and feelings as a parent or caregiver it will empower them to take some responsibility for their own health and wellbeing.

I’m frustrated by their lack of motivation to try anything I suggest.

Discussion

Feeling lethargic and demotivated is a core feature of many mental health problems and so try not to feel too frustrated when your child is not motivated by your suggestions. Try to remain patient, which isn’t always easy, and allow them time and space to explore different ideas which in time may motivate them to make some changes.

It is a constant worry and I can feel helpless.

Discussion

It is only natural to worry about your child and feel helpless when you cannot solve their problems for them. If you can remain calm and strong and help them to explore and find the help they need, this will provide important support for them. It also projects an important message to them that you trust them and appreciate that they do have strengths and skills which they can develop for themselves.

This activity required you to exercise empathy, putting yourself in the other person’s position and trying to understand what they were experiencing. You may have had similar concerns yourself, and if so, perhaps you found some reassurance from the comments provided here. Coming up with a helpful response can sometimes take practice and will differ with each individual.

A research team in Australia took an innovative approach to researching mental health. They asked parents about their concerns regarding the mental health of their adolescent children, and then also surveyed the adolescents about their perceptions of the issues causing concerns (Cairns et al., 2019). The parents most frequently reported being concerned about drug use, depression, friendships and peer pressure, anxiety, school and study stress, and bullying. Although the young people responding to the survey echoed these matters, they also identified ‘sex, sexuality, and gender identity’ as concerns – ‘topics that parents reported feeling the least confident talking to their children about’ (Cairns et al. 2019, p.65). By the end of this course, you should be able to tackle sensitive topics such as these with more confidence.

Before you move on to learning about active listening, have a look next at some advice on talking with your child and particularly the importance of checking in with them and approaching a difficult conversation.

2 Talking and listening

If you are worried out your child or a child you work with, it is important that you set aside some time where you can check in with them and get a sense of how they feel and perhaps how they are managing their lives at that time.

Activity 2: Checking in

Watch Video 2 in which counsellor John Goss discusses how you can check in with your child or a child you are working with or know well.

Transcript: Video 2: John Goss: Checking in

As you watch this clip, jot down a few notes on the key suggestions from John.

Discussion

John suggests that it can be helpful for you to show an interest in some of the things that your child is involved in as a way of establishing a common ground for further conversations and perhaps conversations which are difficult. He also thinks it is important to be open with them in telling them that you have noticed something has changed in how they are behaving.

An important first step in understanding how your child or a young person you are working with is feeling is to stop and listen to them. This might sound fairly obvious as we all talk and listen throughout our day and yet listening is quite a complex skill. How can you become a better listener? Perhaps you already think you are really good at listening but need to extend your skills to help a young person who is struggling.

2.1 Active listening

Active listening became a professional skill largely thanks to the American psychologist Carl Rogers (1902–1987), who developed a ‘person-centred approach’ to therapy. This approach involved focusing closely on the speaker, not only listening to their words but also to the expression of their voice and other aspects of body language. It also involved portraying warmth and care, helping the speaker feel safe to share unsettling thoughts and feelings (Barrett-Lennard, 1999). Counsellors often undertake many hours of training to achieve this type of skill. However, it is important to note that on a basic level, a lay person can learn to offer warmth, support, guidance and structure to help someone find solutions.

In the next activity you will reflect on the importance of listening to young people who are experiencing distress.

Activity 3: Just listen

Watch Video 3 where Pooky talks about different strategies to talk with and listen to your child. As you watch make notes on the four key messages.

Transcript: Video 3: 4 ideas for supporting a child with anxiety

Discussion

| 1. Just listen. Do not fill in the gaps or try and fix things. Try and remain calm. |

| 2. Do not be afraid of silence. |

| 3. Prompt young people to talk. Ask questions and use their words when you summarise and reflect back to them. |

| 4. Agree some next steps. |

Active listening is a technique that shows the young person you are giving them your attention and are doing your best to understand what they are telling you. It can encourage young people to talk because it shows that they are being understood and that the information they are sharing is being listened to and acknowledged.

2.2 Question types

Another way of encouraging people to talk and showing you are interested as Pooky suggests is by asking ‘open questions’ rather than ‘closed questions’. An open question invites a free choice of answer, whereas a closed question tends to elicit a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer. Compare the two questions below:

- Did you play football today at school?

- How did you find school today?

It would be easy to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the first, whereas the second question could open up a range of different answers.

There are also times when a carefully worded observational statement can encourage a young person to confide in you: ‘I’ve noticed you haven’t been catching up with many of your friends, seems like things are difficult at the moment’ (Stem4, n.d., p.1)

Quite often, the challenge is to know what to say next, and how much time you should give if there is a period of silence. Epic Friends, a website that guides young people to support one another, makes the following suggestions for good listening:

- Giving people the space to talk, by not interrupting.

- Don’t immediately dash in with reassurance and solutions.

- Acknowledge what the person is saying, by simply stating what you think you have heard, e.g. ‘it sounds like you don’t know what to do’.

- Notice how you are feeling as you listen, and whether your emotional responses are stopping you from listening properly. (Epic Friends, n.d.)

As a parent or caregiver, it can be easy to feel defensive or guilty when a young person who is close to you shares dark or troubling thoughts. It’s quite normal for parents to feel responsible and to find it difficult to disentangle their desire to ‘solve a problem’ or their fears about being part of the problem, from the process of allowing a young person find their own solution. Bringing your own background anxieties into the conversation can limit your ability to listen openly. Removing your self-defence filters and focusing back to the young person next to you can help them immensely.

It can be easier for therapists than parents to handle a young person’s difficult thoughts and emotions because they are not personally involved in the young person’s life. In Session 8, you’ll learn more about how trained therapists can help. In the next activity you’ll consider how you might approach a difficult conversation and be an ‘anchor’; for your own child or a young person you are working with.

Activity 4: ‘Be a child’s anchor’

Watch Video 4, in which two workers from the YoungMinds Parents Helpline share tips for approaching difficult conversations. Then, work through steps a,b and c below.

Transcript: Video 4: Difficult Conversations - Roundup | YoungMinds Parents Lounge

2.3 Conversation starters

YoungMinds remind us that parents and caregivers know best when their child is not ready to talk, or not in the right mood. In these situations, it is important that young people know they can re-start the conversation when they are ready. In addition to conversation starters, ‘encouragers’ can help a young person who is finding it difficult to open up. Conversation starters suggested by YoungMinds (2020) include:

This next activity takes you beyond simply listening towards techniques that can help you to offer practical solutions for your own child or a child you are working with to learn techniques in self-soothing or calming.

Activity 5: Supporting young people to manage their emotions

Supporting young people to manage their own emotions and learning self-care and perhaps self-soothing techniques is an important life skill.

Step 1: Watch Video 3 again, and listen to Pooky talk about some of the tips for supporting a child’s anxiety and to develop their own self-soothing techniques.

Transcript: Video 3: (repeated) 4 ideas for supporting a child with anxiety

Discussion

| 1. Listen – stop and listen physical, emotional. |

| 2. Begin to encourage them to question the thoughts and feelings – is it true? Accurate? Question the validity. |

| 3. Practical approach – what are the triggers? Person, place, activity? Can we avoid them? E.g. someone who is a bad influence. Other things can’t be avoided and may need to be confronted. |

| 4. Work with them to find ways to soothe and calm. During a time of calm. E.g. breathing techniques, writing, singing, listening to music, drawing, colouring. Put triggers and solutions together. |

a.

Encourage supportive friendships

b.

Encourage them to see the positives, despite their difficulties

c.

Encourage self-compassion, not blaming themselves or feeling selfish about self-care

The correct answers are a, b and c.

Next, you’ll learn about ways for you and the young people you care about to maintain their mental health by focusing on diet, exercise, and sleep.

3 Food, exercise and sleep

Health and wellbeing are dependent on diet, exercise and sleep, and these three aspects of lifestyle are linked to mental health. Enjoying a family meal, getting out in the fresh air or playing a team sport, and having a good night’s sleep could give immediate benefits to a young person’s mood. Longer term, healthy living habits promote healthy growth and development of body and brain. This section addresses the questions ‘How do healthy lifestyle habits support mental health?’ and ‘How can you encourage a healthier lifestyle without making things worse?’

As you work through this section, you will notice that much of the evidence for the mental health benefits of these lifestyle factors is nevertheless tentative. It is often not possible to determine whether adopting healthy lifestyles can improve mental health, or whether researchers are just observing that the two are linked for other reasons. This section will guide you carefully through the scientific evidence and mental health practices that link lifestyle with mental health.

3.1 Food and mental health

Adolescents may develop anxieties around eating and body weight, as you saw in Session 3. If you can become well-informed about the characteristics of a balanced diet and understand that no single food source is a panacea for any particular problem, you can put yourself in a stronger position to help.

The UK National Health Service (NHS, 2018) highlights that in adolescence there is a particular need for certain vitamins and minerals:

- Iron (especially in girls)

- Calcium (Particularly for bone and teeth development)

- Vitamin D (to aid absorption of calcium into the body)

The NHS also emphasises the importance of eating breakfast, a range of fruits and vegetables (‘5 a day’) and cutting down on snacks that are high in fat, sugar or salt. A balanced diet is considered to comprise (NHS 2018b):

- at least 5 portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables every day

- meals based on higher fibre starchy foods like potatoes, bread, rice or pasta

- some dairy or dairy alternatives (such as soya drinks)

- some beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other protein

- unsaturated oils and spreads, eaten in small amounts

- plenty of fluids (at least 6 to 8 glasses a day)

Eating well can help to maintain physical health (which is good for the physical brain, of course), and there is mounting evidence that a balanced diet can support good mental health too (Adan et al., 2019). The missing piece is to do with being able to explain the science with certainty, and to predict with confidence how a change of eating habits will affect mental health. Consider the links between food and mood described in the next activity.

Activity 6: Food and mood

a.

Being a role model of good eating habits.

b.

Talking in a positive way about healthy eating.

c.

Involving the young person in meal planning.

d.

Involving the young person in food shopping.

e.

Involving the young person in meal preparation.

f.

Stocking up on healthy snacks.

g.

Involving the young person’s friends or siblings.

The correct answers are a, b, c, d, e, f and g.

Discussion

If you feel enthusiastic about any of the options, you could start practising some of these options in your daily life.

3.2 Exercise and mental health

Exercise benefits everyone but most people struggle to integrate sufficient physical activity into their lives.

For young people, the World Health Organization recommends ‘at least an average of 60 minutes per day of moderate-to vigorous-intensity, mostly aerobic, physical activity, across the week’. (WHO 2020a, p. 25)’. The evidence for the physical benefits of exercise is well established, and the evidence for psychological benefits is mounting. In the next activity you will consider some of the research in this area.

Activity 7: Can 10 minutes exercise a day can improve mental health

Listen (or watch) Video 6 where Dr Rangan Chatterjee talks to Dr Brendon Stubbs. Try not to get too bogged down in detailed descriptions of research approaches here. Whilst they are important, it’s perhaps more important to consider what the key messages here are in terms of the amount of exercise and how this can impact mental health. As you listen make a note of three key messages which you feel are important.

Transcript: Video 6: How 10 Minutes Of Exercise A Day Can Change Your Brain: Dr Brendon Stubbs | Bitesize

Discussion

There are many important messages presented in this podcast and you may have been surprised that it takes as little as ten minutes a day of gentle exercise and moving to have an impact on mental health. These changes can be quite significant, as Dr Rangan Chatterjee and Dr Brendon Stubbs describe, including neuroplasticity and changes to brain activity and function. Furthermore, they discuss how these changes can take place in a relatively short period of time. This can provide important information for young people who are experiencing mental health problems who may feel lethargic and find the thought of intensive exercise daunting and hard to become motivated for.

WHO (2020b) has claimed that there is ‘Strong evidence’ that ‘physical activity reduces the risk of experiencing depression’ (p. 39) and can help to treat existing depression. WHO also warns about the health risks of excessive sedentary behaviour, which can occur, for example, when recreational activities are screen-based rather than physical.

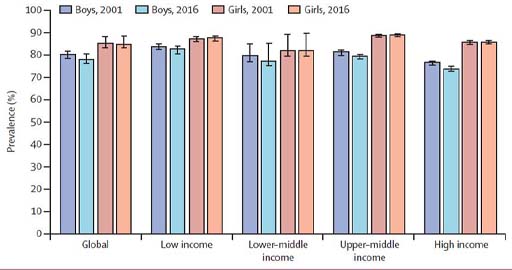

The latest figures suggest that very few young people are achieving the WHO recommended levels of physical activity (Guthold et al., 2020). The figure below, which shows the prevalence of insufficient physical activity among school-going adolescents, reveals that globally more than 80% of girls did not achieve the recommended level in 2016, and that boys were only slightly better. There is no clear pattern between rich and poor countries. The trend shows a slight improvement for boys between 2001 and 2016, and hardly any change for girls.

Research on the relationship between physical activity and mental health usually raises further questions. For example, are team sports better for mental health than exercising alone? A recent European survey study (McMahon et al., 2017, p. 120) found that ‘Lowest levels of anxiety and depression and highest level of well-being were found among those participating in team sports’. However, the researchers could not say whether the social aspects of team sport improved mental health and wellbeing, or whether the young people with mental health problems were less likely to engage in team sports.

The amount of exercise required for mental health might not be quite as great as that for maintaining physical health. Indeed, The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, n.d.) recommends ‘45 minutes to 1 hour per session, up to three times a week’ for an adolescent who has a diagnosis of depression. As more research results become available, people’s understanding of the relationship between mental health and physical activity will become more sophisticated. Increasing one’s levels of physical activity can benefit some individuals more than others, and it is definitely something worth persevering with, in efforts to boost mood.

Research note

It is difficult to make definite claims about whether physical activity actually prevents mental health problems, because most studies are ‘cross-sectional’. A cross-sectional study takes a snapshot at a particular time, by conducting a survey, for example. Surveys can determine how many people who engage in a certain amount of physical activity are experiencing mental health problems (providing a correlation), but they cannot tell whether the activity is preventing mental health problems from developing. Longitudinal studies, which measure changes over time, can help to fill these knowledge gaps, although the causes of mental health problems are so complex it can be difficult to identify the effects of a single factor. Randomised controlled trials are able to measure the effects of a single factor through careful design and the use of sophisticated statistical methods. These are the most difficult to set up, but provide the most conclusive results.

One of the ways in which exercise is thought to be beneficial is by improving sleep quality (Brand et al., 2017). Daytime exercise is beneficial, whereas vigorous exercise late in the evening can interfere with sleep. Next, you’ll explore the impact of sleep on mental health, as well as ways of helping a young person to sleep better.

3.3 Sleep and mental health

You’ve probably had times when you were unable to sleep and as a result felt tired, grumpy and were unable to concentrate well. Sleep can be particularly important during adolescence. Sleep disruption can exacerbate depression (Baum et al., 2014), and it is widely accepted that good sleep is essential for good mental health. Many young people may report feeling excessively tired when experiencing mental health problems and many parents or caregivers may notice that their child is sleeping a lot or experiencing disrupted sleep.

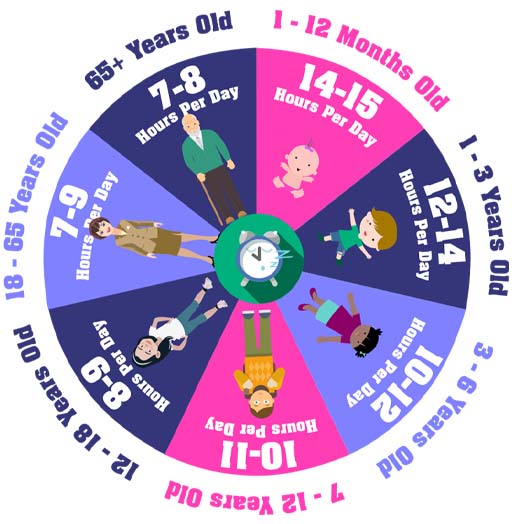

Before learning more about this, consider how much sleep a young person needs.

Activity 8: Sleep needs in adolescence

a.

4-5 hours

b.

6-7 hours

c.

8-9 hours

d.

10 hours or more

The correct answer is c.

There are some important considerations regarding sleep in adolescence. One is that sleep seems to have an effect on the development of the brain structure in adolescents. It is also understood that restricted or interrupted sleep can affect learning and memory as well as the processing of emotions (Short et al., 2013, Tarokh et al., 2016). There is little doubt that good quality sleep restores the brain, and that the adolescent brain is undergoing significant structural changes. Scientists still have much to learn about the relationship between sleep and the adolescent brain, and this remains an active area of enquiry.

During adolescence, the internal body clock shifts so that a young person tends to go to sleep later at night and wake later in the morning. This shift in body clock tends to disadvantage young people, who find it difficult to wake for school and get to sleep at a good time in the evenings (Crowley et al., 2006).

External factors, such as light, also influence the body clock. Neuroscientists have found that light at the blue end of the spectrum enhances alertness, whereas red light can reduce alertness. Exposure to natural light during the day, which has high levels of blue light, can enhance healthy sleep patterns in young people, and reducing blue light before bedtime can help a young person get to sleep (Studer et al., 2019). There is growing concern over screen use in the bedroom as screens typically emit blue light.

The evidence for the benefits of good sleep is persuasive, so what can you do as a parent or caregiver? The next activity helps to answer this question.

Activity 9: Promoting sleep

a.

strenuous physical exercise in the hour leading to bedtime

b.

using a smartphone, tablet or PC in the hour leading to bedtime

c.

watching TV in the hour leading to bedtime

d.

drinking caffeine, particularly in the 4 hours before bed

The correct answers are a, b, c and d.

a.

reading a book at bedtime

b.

listening to relaxing music

c.

having a bath

d.

change bedroom lightbulbs to ones with a warmer light

e.

write down any worries that are interfering with sleep

f.

aim for at least 60 minutes’ exercise during the day

g.

get outdoors as much as possible while it is light

h.

a good bedtime routine

The correct answers are a, b, c, d, e, f, g and h.

a.

thicker curtains or a blackout blind in the bedroom

b.

using an app to support good ‘sleep hygiene’ (the good habits that facilitate sleep)

The correct answers are a and b.

4 This session’s quiz

Check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you’ve finished.

5 Summary of Session 6

The main learning points of this session are:

Active listening provides opportunities to engage with young people and provide time and space for them to share their feelings. This involves stopping what you are doing, listening without interrupting and trying not to judge a young person or trying to fix them.

Rather than trying to solve a young person’s distress it is important that they learn and are supported in developing life skills in self-soothing and the ability to calm themselves.

A healthy lifestyle, including a healthy diet, regular exercise and plenty of sleep supports young people’s mental health.

Now to go Session 7.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Victoria Cooper, Sharon Mallon and Anthea Wilson and was published December 2021. We would also to thank Jennifer Colloby, Steven Harrison and Karen Horsley for their key contributions and critical reading of this course. We would like to thank the parents, young people and professionals who shared their experiences with us.Their willingness to share sensitive and highly personal accounts of having or supporting those with mental health challenges adds greatly to this course and we will hope will benefit all those who find themselves in similar situation.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below (and within the course) is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Session 6: Supporting young people

Figures

Figure 1: Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock.com

Figure 2: Centre for Mental Health 2017 https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/ https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/ mental-health-among-children-and-young-people

Figure 3: IAN HOOTON/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Figure 4: interactive (text adapted from): CAMH service tiers (icptoolkit.org)

Figure 5: John Birdsall John Birdsall (john-birdsall.com)

Figure 6: from: Figure 1: Prevalence of insufficient physical activity among school-going adolescents aged 11–17 years, globally and by World Bank income group, 2001 and 2016 The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health

Figure 7: KindPNG https://www.kindpng.com/

Audio/Video

Video 1: Another Way: Young people talk mental health: Courtesy Youth Access and Eye Opening Films (Producer)

Video 3: 4 ideas for supporting a child with anxiety. Courtesy Pooky Knightsmith Mental Health https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VbMUMFxjv40 https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by/ 4.0/

Video 4: Difficult Conversations - Roundup | YoungMinds Parents Lounge Courtesy: Young Minds https://www.youngminds.org.uk/ https://youtu.be/ nrXBaSOd6F8

Video 5: How to manage your mood with food | 8 tips: Courtesy: Mind - the mental health charity https://www.mind.org.uk/

Video 6: How 10 Minutes Of Exercise A Day Can Change Your Brain: Dr Brendon Stubbs | Bitesize This excerpt is taken from Episode 97 of the Feel Better Live More podcast hosted by Dr Rangan Chatterjee. https://drchatterjee.com/ how-exercise-changes-your-brain-and-reduces-your-risk-of-depression/ https://drchatterjee.com/ blog/ category/ podcast/

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – The Open University.