Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 2:43 PM

Session 7: Identifying sources of support

Introduction

A great source of distress for young people who experience mental health problems are feelings of isolation. You will recall in Session 6 that the parents of the young people who were experiencing mental health problems reported that they also withdrew from families and friends. Isolation is often compounded by a sense of stigma. Support networks can be invaluable in assisting young people and their families. It can help them to manage any stigma they may feel in relation to their mental health and help them to feel connected with others who understand the challenges. It can also help them find sources of support. Internet technology has made it possible for people to link with others in the privacy of their homes, and the opportunities to do this continue to develop and have showed some positive results. This has been particularly the case during the COVID-19 pandemic when options to meet in person were limited. In the next video, you’ll see counsellor John Goss talking about the various types of support that in their experience young people have access to. Watch now to get a sense of the range of support.

Transcript: Video 1: John Goss: Various types of support

In the video, John talks about the GP and talking therapy with a counsellor, as being two of the main formal support systems that a young person can access. You will learn more about these types of support in this session. However, as John pointed out, it is also important to sometimes engage directly with the young person and/or the people around them to find out what types of things could best support them.

In this session, you will begin by exploring how a secure network of family and friends can help to support a young person. At the beginning of the video, John also talked about the power of support groups in relation to providing spaces for the young person to share their experiences. Some of these can be in person, but as you will discover nowadays many are held online or via social media. When well-managed, these can be a good source of support and this session contains some valuable information on how young people can be encouraged and supported to use social media for the benefit of their mental health. We will also explore how it can impact negatively and how this can be managed. You will then consider what the charities MIND and YoungMinds can offer to young people with mental health problems.

Learning outcomes

By the end of the session, you should be able to:

describe how a support network can benefit a young person experiencing mental health problems

advise a young person on the best way of using social media for support

explore a range of self-help resources and decide whether they will be helpful.

1 Family, friends and other adults

Addressing mental health issues is far from a passive process on the part of the young person concerned. Professional support strategies rely on the young person being able to engage actively in the process, as so much of it is about developing relationships with the self and others. As you will see in the case of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which you will look at in Session 8, young people can improve their mental health by challenging and adjusting the ways they think about events and their emotional responses to their experiences.

Dr Ken Ginsberg, specialist in adolescent medicine, advocates supporting young people to develop the skills they need to develop competence in life. You heard him in Session 5 talking about the ‘Seven Cs of Resilience’. You’ll hear more from him in the next activity.

Activity 1: Nurturing and supporting in adolescence

In Session 5 you were introduced to the Seven Cs of Resilience, by Dr. Ken Ginsburg. In the video it was clear that resilience is not one clear definable thing but something that is more complex and influenced by a range of factors, both internal and external to the young person. The topic of Session 7 is about identifying sources of support, so this time we want you to watch the video again, this time focusing this time on ways in which those around the young person can contribute to their resilience.

Complete the table below as you listen to the video again, this time making a note of all the things that those around a young person can help to support a young person’s sense of resilience.

Transcript: Video 2 (repeated from Session 5): The Seven Cs of Resilience: Dr. Ken Ginsburg introduces his Seven Cs of Resilience: Confidence, Competence, Connection, Character, Contribution, Coping, and Control. Content provided courtesy of the Center for Parent and Teen Communication, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. © 2018 The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

| 1. Confidence | |

| 2. Competence | |

| 3. Connection | |

| 4. Character | |

| 5. Contribution | |

| 6. Coping | |

| 7. Control |

Discussion

| 1. Confidence | Those around a young person can help by building their self esteem. While also ensuring not to overly place pressure on them to perform. |

| 2. Competence | Those around the young person can notice what skills they have and comment positively on those already in place and further influence the development of new skills. |

| 3. Connection | Having circles of adults who ‘see’ them, and who are reliable can help young people connect. It also gives them security to meet challenges that arise. |

| 4. Character | Those around the young person can help to provide boundaries for them and connections with family. |

| 5. Contribution | Helping young people know that they matter but also knowing that they can reach out to others for a helping hand is a clear part of contribution. But it’s important to know that this is done ‘in kind’ and that there is no pity that comes with it. |

| 7. Coping | Telling young people what not to do by shaming them doesn’t work, so those around the young person need to work with them to help them learn better ways to cope by modelling this behaviour. |

| 8. Control | Young people begin to have a sense of control within their homes and watch how those around us teach us be in the world. Those around them can also teach them responsibility. |

1.1 Fostering supportive networks

The value of a supportive social and family network should not be underestimated. In Session 5, you found that having a supportive social network is a key feature of resilience. A strong social network also instils a sense of belonging, which can promote wellbeing. Psychologist Nathaniel Lambert and colleagues (Lambert et al., 2013, p.1425) identified that ‘Having a sense of belonging is to have a relationship with people, or a group of people, that brings about a secure feeling of fitting in.’ Therefore, when considering a person’s social network it will also be useful to think about the quality of the relationships.

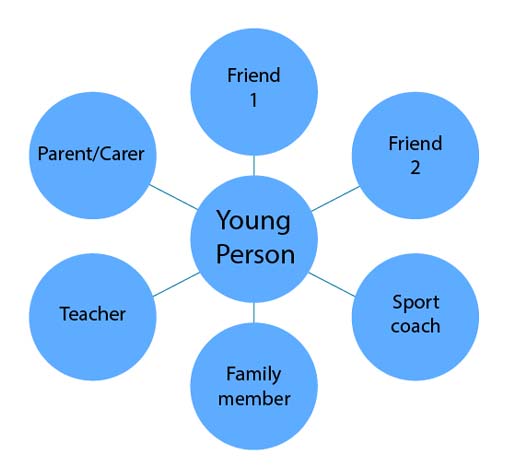

Research has shown that parents, best friends, peers, relatives, siblings, teachers and other practitioners and members of the community can all be a source of secure relationships for a young person (Buckley et al., 2012). Look at the diagram in Activity 2, which gives an illustration of a close social network for a young person.

Working out who is part of a young person’s social network can be a first step towards helping the young person to access support from trusted sources. The next activity will help you to map out the social network of a young person you know, and invite you to do the same for yourself.

Activity 2: Social support networks

Spend a few minutes thinking about the people in the life of a young person you know well. It could be a family member, friend, neighbour, or someone you know from education or sports activities. It might be a young person you know about through another adult.

Fill in the social network for this young person the best you can. Then, consider which of these relationships might be the strongest for providing a sense of belonging or trust. You might find it helpful to think back to Ken Ginsberg’s advice about how to support an adolescent with their competence in organisational, communication, self-advocacy skills, and to understand how to handle peer pressure.

Why not do the same for yourself? Being in a position to support others means that you also need a good social network for your own wellbeing. Consider who might be able to provide good quality support to you. It may be that there are a few individuals who provide slightly different aspects of the support you need.

Discussion

There are no right and wrong answers to this activity as each individual’s personal circumstances are different. It is likely that some of the relationships you have identified include people the young person knows really well and may be emotionally close to, such as family members or friends, while other relationships, though important, are with people whom they are not emotionally close to, such as fellow students, members of a social group or team members. It is important to note that emotional closeness in relationships of course depends upon the quality of the relationship they share with network members. What the activity highlights is that each person is part of a network of relationships of different kinds and varying degrees of importance.

Note that networks may change over time; they grow, shrink and shift. As a person moves through adolescence, their peers may become more important than their close relatives. School transitions and changing family dynamics can be disruptive and adapting to these changes should be seen as a natural part of development.

1.2 Managing barriers

In Activities 1 and 2 of this session you have seen how social networks can nurture and strengthen a young person’s emotional health. Research has shown that participating in school-based extra-curricular activities can help to reinforce existing friendships and help new friendships to form (Schaefer et al., 2011). However, it is also important to note that socialising may be a trigger for some young people who feel socially anxious and/or depressed (Martin and Atkinson, 2020). ‘Withdrawal’ from social networks and family can characterise many mental health issues and exacerbates feelings of social isolation, and can also heighten stigma. Therefore, in thinking about a young person’s social network and the influence it has on a young person’s wellbeing, you might consider whether you can suggest ways it can be strengthened or supported. You may also wish to include reviewing any disruptive influences that you think there may be on the young person or improving your confidence in responding to distress. We turn to ways to do this in the next section.

Is it also important to note that a young person may not always want to confide in close family or friends, especially if they are concerned about stigma or worried that they will upset the relationship. It is important to understand barriers to accessing support and this is something we explore in the next activity.

Activity 3: Barriers to accessing informal social support

Listen to the young men we interviewed discuss how they perceive their friends might feel about reaching out for support in relation to mental health. Pay particular attention to any tensions they report in relation to how mental health is thought about by them and their peers.

Transcript: Video 3: Barriers to support

Answer

They start by talking about how some of the young men they know would be embarrassed to talk about their mental health because of the need to keep up a bravado. They also discussed the importance of mental health campaigns that help to reduce stigma. However, this was a source of disagreement among the young men as they reported varied opinions about whether this awareness can also create additional embarrassment. This disagreement is a further example of how individuals react and perceive information on mental health differently. Furthermore, it shows the importance of not making assumptions about how young people react to these campaigns.

As the clip you just listened to highlights, there is still a great deal of work to be done to get young men to open up about their emotions. Embarrassment seems to be a key barrier to talking about mental health, but there are things that we can do to support young people to enable them to discuss these issues.

Although a personal network is essential in many ways to support wellbeing and/or recovery from a mental health problem, it is important to acknowledge that supporting someone with mental health issues can be a challenge to us. This is something you’ll explore in the next section.

1.3 Managing responses to mental health disclosures

When a parent or carer is supporting a young person who has confided in them about issues with their mental health and emotional difficulties it can feel overwhelming.

Research shows us that self-care and a network of support for carers is vital in ensuring that when parents, caregivers and educators feel out of their depth, they have support for themselves. However, not everyone knows how to respond when they are told about mental health issues.

Activity 4: Experiencing different supportive responses

Listen to this audio from one of the parents we interviewed as she talks about how people reacted when she shared the news that her daughter was experiencing mental health issues. Note the positive and negative aspects and reflect upon how this might impact your behaviour in future if you were told that a friend or colleague was supporting someone with mental health issues.

Transcript: Audio 1: Support for parents

Answer

This parent describes how regular contact and offers of support were vital to her. However, she also experienced unhelpful responses which dismissed the seriousness of what her daughter was experiencing. Overall, background support and direction were of the greatest help to her.

Being exposed to the various responses different individuals may express in response to disclosures about mental health can be challenging. However, often at least part of the problem is that often there is a lack of understanding about mental health distress. You may even find that as a parent, caregiver or educator you are taken out of your comfort zone and challenged beyond your own limits of understanding about these issues. This is why education about mental health distress and how to manage it is so important.

In response to these challenges and in an attempt to improve support and reduce stigma, bespoke training courses have been set up for those who wish to find out more about how they can support and help young people. For example, the training company Mind Matters have developed an adapted version of the popular Mental Health First Aid course to ensure the content is more specific to young persons’ mental health.

Other examples include that offered by Papyrus, a charitable organisation working to prevent young suicide which offers three different types of training for schools and colleges ranging from short courses that can be completed in an afternoon that give a brief overview of the main topics, to more intensive two day courses that build up skills.

While these courses are more formal and therefore have costs associated with them, there are also many other free courses on OpenLearn and FutureLearn that deal with particular areas of concern that you may want to know more about. If you wish to find out more you can simply enter relevant search terms into the search engines both online portals provide.

Some of the parents we spoke to thought it may also be useful for parents and supporters to have counselling themselves. This can provide a safe space to talk over the feelings experienced when supporting someone who has mental health difficulties.

2 Social media

Social media gets a lot of bad press about its negative impact on young people (as well as adults). Research indicates that social media is implicated in increasing adolescent depression (Brunborg and Burdzovic, 2019; Raudsepp, 2019) especially in girls (Kelly et al., 2019). It also provides a platform for narcissistic self-promotion and aggression (Stockdale and Coyne, 2020) and acts as a mediator of body image concerns (Marengo et al., 2018). By contrast, however, there is also evidence that social media can provide a supportive environment for young people to make connections and receive mutual support (Radovic et al., 2017).

In the UK, it is becoming compulsory to include online safety in school curricula (Department for Education, 2019; Welsh Government, 2019; CCEA, 2020; Scottish Government, 2017). Many young people are well briefed on online safety, although this doesn’t mean, of course, that they will take all the precautions they have been taught. In the next activity, you will find out about how a young person you know engages in social media and the impact this may have on their mental health. In this section, we will explore these issues by listening to audio and watching video from our interviews with young men and women.

Activity 5: Assessing the Impact of Social Media Use

In this activity, you will explore the varying impacts of social media on young people by watching a series of clips from our interviews with young men in which they are asked to talk about the impact this has had on their lives.

2.1 Taking control

Researchers and charities are increasingly working to explore how to guide young people to manage their relationship with social media so that it has more of a beneficial impact on their wellbeing. In the next activity, you will explore some of the simple techniques they have developed.

Activity 6: Controlling a social media feed

Regardless of your personal opinions of social media and the role it is playing in the lives of the young people you work with, it is important to realise that young people are best supported by helping them to make good personal choices about social media for themselves, especially as many adolescents have individual access to mobile phones and computers. In the previous activity, you heard the young men describe how they limited their use of social media to manage the impact it had on their mental health. Watch Video 6 in which young people describe how they altered their behaviour to have a more positive time when using social media.

Transcript: Video 6: #OwnYourFeed for a more positive time online

As you watch make notes summarising the following three key pieces of advice:

- ‘Cleaning your feed’

- ‘Find your crowd’

- ‘Say hey’

Answer

This video illustrates three simple steps to helping a young person manage their social media and the impact it has on their emotional health. The key here is the message of ‘cleaning your feed’ and at its core is the idea that young people should consider how each post makes them feel and to mute or unfollow those that do not keep them interested or happy. The second step is to use social media to find like-minded people who share their interests. The final step is to use social media to connect with people, to reach out and say hey.

It can be hard to talk to young people about these things in a way that captures their attention, so it may help to ask the young person to watch the video themselves. However, campaigns like this which are driven by and informed by young people are an illustration of how many of them are increasingly aware of the impact of social media on their mental health.

Another way to help young people engage with their own social media use is to access the reminders that tell them how long they’ve been using an app or to set their own limits. For example, on Facebook, go to Your time on Facebook > Set daily reminder. They can then set their own ideal daily usage.

Being able to limit time spent on social media can also help to prevent sleep disruption. There is now a body of research that indicates ‘young people who spend more time using social media (especially at bedtime) and those who feel more emotionally connected to platforms’ report later bedtimes, take longer to get to sleep, sleep less and have poorer sleep quality (Scott et al,. 2019, p. 539). You learned about the link between sleep and adolescent mental health in Session 6. Fortunately, there are ways to mitigate sleep disruption or to use phones to help promote sleep. For example, most phones now have night time modes to ensure that blue lights emission is reduced. In addition, meditation apps have stories that can help young people wind down and get to sleep.

2.2 Understanding the impact of social media on a young person’s identity

New research can help us to understand the complex ways in which young people engage with the online world as part of their everyday lives. For example, the internet and social media use can serve as a means of self-interpretation, allowing young people to conduct ongoing ‘identity work’. These digital technologies can make it possible for us to create ‘multiple selves’ or ‘multiple identities’ allowing young people to transform themselves. In addition, it can allow young people to connect with other people who are like them.

Activity 7: Understanding the impact of the internet on identity

The young people who are growing up today where born into a world were the internet and social media already existed. In their book on the subject, John Palfrey and Urs Gasser described them as being ‘Born Digital’ and suggested this had a fundamental impact on how their identity was formed. One of the key messages from the book is that it is not always possible for those of us who grew up in a time pre the internet or social media to fully connect with the integrated nature of the digital identities that many young people have these days. But it is important for us to recognise that, as with most things in life, there are both positive and negative consequences.

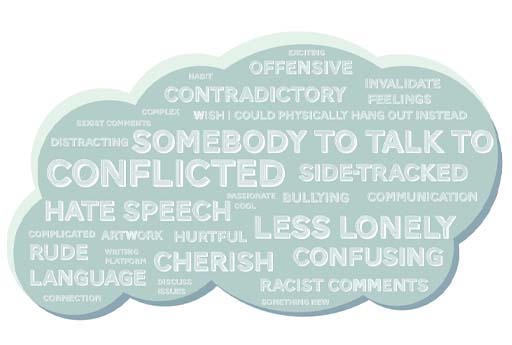

Watch this video which illustrates well the complex relationship some young people have with social media.

As you will see from the word cloud (Figure 4), individual reflections on social media and the ways in which young people use it can vary from our own. From this video and from the extracts of interviews with young men it is clear that we should be careful about buying into the notion that all social media is bad for young people. Instead, we need to move towards an understanding of how and why young people engage with various social media networks.

3 Charities

What happens if a young person does not feel able to confide in close friends and family? Charities provide a range of important services for supporting mental health in young people. Their websites are often the first place people go for information.

Charities such as Mind and YoungMinds provide support networks for young people. Mind, for example, has linked up with the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families, which has a network of centres across the UK that provide support for young people. Mind, itself, has a network of ‘Local Minds’ based in certain localities, and which are able to provide local support. Similarly, YoungMinds acts as an information hub, bringing together a range of organisations that can help young people.

In this section, you’ll find out about some of the help charities provide directly to young people.

3.1 Helplines

COVID-19 has severely restricted people’s ability to engage in face-to-face support. However, as many young people now commonly use social media platforms to communicate with their peers, it is possible to harness these skills to encourage them to engage with other sources of support. There are now lots of ways for young people to reach out for support using technology. In the next activity, you will consider some of them.

Activity 8: Exploring sources of support through technology

Think about a young person you know and if you can, ask them about the different kinds of support they have accessed so far. Tick the one you feel is the most useful or important. There are no right or wrong answers here. Your response will feed into a poll so that you’ll be able to see which kinds of support young people most commonly access amongst learners of this course.

Answer

How did your answer compare to those of your fellow learners? Perhaps you were surprised at how acceptable these forms of support are now. Or perhaps you are well versed with these alternatives to online services. Studies now show that people are increasingly accepting electronic communication to help with their mental health distress. This is particularly the case with the onset of COVID-19 which has pushed the issue further, forcing many organisations online and improving the ways in which they are used.

Whatever your attitudes towards online sources of support, it is now hard to ignore the potential value of the peer support and a feeling of connectedness it offers. Given that young people are enthusiastic users of mobile apps, there is growing interest in developing digital methods of connecting young people to sources of help from both peers and professionals (Bohleber et al., 2016). Easton and colleagues (2017) have discussed the distinction between improvements from a medical perspective of mental health in contrast to ‘social connectedness, personal empowerment, and quality of life’. Fortuna and colleagues (2019) see online peer support as potentially complementary to medical interventions.

There is still much to learn about the value of online networks, but it is important to realise the wide variation in the nature of online support and if a young person is finding it helpful, that may be the most important consideration.

3.2 Online forums

One of the most important aspects of online supportive resources is that they are frequently accessible at very short notice and are often accessible 24-hours a day. This can be an important aspect as it allows young people to reach out whenever they are struggling and when they might think it is not appropriate to reach out to more formal sources of support.

Self-help for adolescents can be supported online via websites and mobile apps. Many charities now provide support directly to adolescents via their websites. For example, YoungMinds and Childline provide advice on a range of issues from bullying to explaining mental health conditions, to asking for help.

Activity 9: Finding help online

In this activity, you are encouraged to work through some of the supportive resources that are available online, both for you and for the young person you may be concerned about. Below we have a provided a list of resources.

Spend the next thirty minutes exploring each of them and make a note of those which you think you may want to revisit at another time. Remember to open these links in a new window so you can return to the course when you are ready. (To open a link in a new window or tab, right-click on the link and select ‘Open in new window/tab’. Or, to open in a new tab, hold the Ctrl key as you select the link.)

You may have noticed while you were reading these websites that they contain a lot of information. It is also important to notice that some of these charities also run some helplines that can provide, in many cases, instant access to a counsellor or trained volunteer. Here are some of the most commonly used that we have come across.

- Hopeline UK – call 0800 068 41 41 if you are having suicidal thoughts

- – Childline message boards 0800 1111 (always open, website includes online counselling)

- Kooth - free, safe and anonymous online support for young people. Monday-Friday Noon-10pm and Saturday/Sunday 6-10pm

- Mermaids – 0808 801 0400 – supporting transgender youth, their families and professionals working with them. (Mon-Fri 9am-9pm)

- The Samaritans – 116 123 / jo@samaritans.org (always open)

- Shout – text SHOUT to 85258. 24/7 free text service for anyone in crisis anytime, anywhere.

- YoungMinds Crisis Messenger – text YM to 8525 for free. 24/7 crisis support.

- YoungMinds Parents Helpline – 0808 802 5544 (Mon-Fri from 9:30-4pm).

In the next section you will explore how apps can provide a form of therapeutic support and treatment.

3.3 Mental health apps

As our understanding of social media has increased, so has the development of apps that help us to monitor and improve our mental health. This area is an ever-expanding part of technology with new apps being developed all the time. These apps cover a range of topics, from those that help to monitor moods swings to those that teach mindfulness-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

Recently, there has been a move towards apps that have been developed with young people, so that their needs are central to the design and content. Research now suggests there is significant potential to improve the lives of young people who are experiencing depression via technology-based app based interventions. As the area changes so rapidly it is difficult to recommend any that will remain relevant in the future. Here we have listed some of the key ones that you may chose to explore in your own time. There will be others that you come across that you may also find useful.

- Hub of hope: An app and online tool to help people with mental health needs to access patient groups, charities and other sources of support across the UK.

- Combined minds: For parents and friends who want to support a young person’s mental health.

- Mental health podcast list

Because apps are constantly changing and the evidence used to develop them is changing, it is hard for us to recommend any for specific use here. However, the NHS has an apps library list aswell as resources here, where they list those that have passed the NHS approval process.

It is also important to remember that for some young people it can provide an alternative form of support, for others it might address their need for support between their face-to-face appointments.

4 This session’s quiz

Check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you’ve finished.

5 Summary of Session 7

In this session you have explored how you can go about both support young people yourself and in supportive networks of other adults and peers. You have also examined how you can find sources of help so that they can engage in self-care. You have heard some young people discuss the impact that social media can have on their mental health and how they have found ways to manage this impact. Finally, you have examined range of online support organisations and mental health apps that exist that can provide both information on mental health and direct contact to helping professionals. Well done, you have now almost completed this course and are ready to turn to the final session.

Now to go Session 8.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Victoria Cooper, Sharon Mallon and Anthea Wilson and was published December 2021. We would also to thank Jennifer Colloby, Steven Harrison and Karen Horsley for their key contributions and critical reading of this course. We would like to thank the parents, young people and professionals who shared their experiences with us.Their willingness to share sensitive and highly personal accounts of having or supporting those with mental health challenges adds greatly to this course and we will hope will benefit all those who find themselves in similar situation.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below (and within the course) is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Session 7: Identifying sources of support

Figures

Figure 2: Lisa/ https://www.pexels.com/ photo/ person-holding-note-with-be-kind-text-3972931/

Figure 3: Rawpixel/Getty Images

Figure 5: (c) Kay Morley https://www.evidentlycochrane.net/picturing-mental-health/visuals-blog-sea-of-google-illustration-by-karen-morley/ https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-nd/ 4.0/

Figure 6: Different types of mental health apps with Logos: Google Play and Apple App Store

Audio/Video

Video 2: The Seven Cs of Resilience: Dr. Ken Ginsburg introduces his Seven Cs of Resilience: Confidence, Competence, Connection, Character, Contribution, Coping, and Control. Content provided courtesy of the Center for Parent and Teen Communication, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. © 2018 The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Video 3: Barriers to support © The Open University

Video 4: Trends in how social media impacts mental health © The Open University

Video 5: Helpful ways of limiting the negative impact of social media © The Open University

Video 6: #OwnYourFeed for a more positive time online courtesy: Young Minds www.youngminds.org.uk

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – The Open University.