Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 2:42 PM

Session 8: Seeking expert support and accessing services

Introduction

Congratulations on reaching the final session of the course! You will have learned a great deal since starting to study this course and you will appreciate how complex mental health issues are, as well as the many challenges involved in supporting a young person. This session goes a little deeper in exploring these many challenges and considers the steps involved in gaining additional help. The session will introduce you to a range of professional interventions that are potentially available should you and the young person decide these might be necessary. It will also explore the referral processes that can help you to gain access to these services. By way of introduction to these topics, listen to the following audio in which a parent explains how they came to view getting help for her daughter.

Transcript: Audio 1: Getting help

In this clip, the parent clearly describes how telling someone to ‘pull themselves together’, or thinking that they might grow out of the emotional issues they are experiencing may not always be the case. Parents often blame themselves for how their child is feeling but as this mum describes, it is important that parents recognise that help is available and can make a big difference to how ther child feels. At the heart of seeking help, it can be important to get a receptive conversation going with your young person as this may prevent the issue developing into something that is more difficult to deal with. But as this mum also points out, this is something you may need professional help to do.

In this session, you will begin by exploring the referral routes available to parents and practitioners working with young people. You will then consider different treatments for young people with mental health problems, before learning more about how talking therapies can help with a range of issues. Practitioners draw on a range of different strategies to help a young person, and you’ll learn more about these too.

Learning outcomes

By the end of the session, you should be able to:

describe the referral processes for a young person experiencing mental health problems to access professional support

identify a range of treatments and support for a young person experiencing mental health problems

discuss the benefits and challenges associated with professional interventions.

1 Responding to concerning behaviours

It can be hard to know what to do and how best to react to a young person who is displaying worrying behaviour. Given the breadth of issues that can be presented that might relate to emotional distress, it can be hard to provide advice on each situation, and if you are worried it is best that you find someone you trust to talk to.

Self-harm is one of the behaviours that a young person who is experiencing mental distress may display and it is one that can be particularly worrying for those around the young person. In Session 7, we also heard the young men talk about how they felt this behaviour may be influenced by trends on social media. While this can be difficult to explore, it clearly causes a lot of concern for many carers, parents and educators. In this session, we will use it as an example of how to respond to a young person you are worried about.

Parents who notice changes in their child’s behaviour may be the first to realise the need for professional help. The typical way most people begin the formal process of accessing professional help for a young person is to make an appointment with a GP. If you are involved in doing this, it might be helpful when making the appointment to ask if any of the doctors or practice nurses have a special interest in mental health.

It is easy to feel the time pressure in a 10-minute GP appointment and the more prepared you are, the better. To prepare for an appointment with the GP to discuss a young person’s mental health, it will help to make some notes on any questions you’d like to ask or anything you especially want to tell the doctor. You might even ask the young person to keep a diary of the challenges they are dealing with.

Activity 1: Preparing for a GP appointment

When people visit a GP it can be hard to remember what they wanted to say. This can be particularly the case when dealing with a sensitive subject such as mental health. It can be hard to find the right words to describe what is creating the feeling of concern. One of the key ways in which you can make the most out of a visit to the GP is to prepare for the visit in advance.

These are some of the questions the doctor may want to ask you about the young person’s problems:

Now visit the following website: Talking to your GP about mental health. Make a note of the key things they say can help you to prepare for a GP appointment in which you, or someone you care for wishes to discuss mental health.

Answer

From the website, we noted that it was important to prepare. Write down what you want to say. Find words that help explain how you are feeling, or print out something that captures what is going on for you. It is also possible to ask for a longer double appointment.

In the video, Mind also suggest that you might want to bring someone with you. This can be particularly important when we are supporting a young person. However, it is also important to note that it is possible for young people to attend the GP alone, and this may be one way of encouraging the young person to seek help. Especially if they are reluctant to share what is going on for them.

GPs and some specialist nurses are able to make a referral to a counsellor employed in the community, or to more specialist services, depending on need. If the young person you are caring for is not referred to specialist services, or is added to a long waiting list, there are still other things that you can do to help support them. You will consider these later in this session.

1.1 Mental health at school

The flow chart in Activity 2 has been developed by researchers at the University of Oxford (Charlie Waller Memorial Trust, 2018). It is aimed at school staff, so if you are a parent or carer you may want to approach this activity in the spirit of understanding the practices underpinning disclosure of self-harm. The essence of this response process can also be applied to other mental health concerns.

Activity 2: Developing a response to mental health concerns at school

Spend a few minutes reading through the process and if you are based in a school, consider whether there are any ways you could develop your knowledge and skills at work.

Consider which of the actions in this chart could apply to you as a parent or in your professional role where relevant. Are there any gaps in your knowledge and skills for taking these actions? Make notes below on ways in which you think you are prepared or could prepare yourself to handle a self-harm situation.

| Actions | Self-development possibilities |

|---|---|

| See to immediate medical needs | |

| Speak to the young person and listen to what they have to say | |

| Speak to the head of year, school nurse, school counsellor or safeguarding lead | |

| Think about confidentiality | |

| Think about circumstances and potential risks | |

| Address ‘lower concerns’ | |

| Address ‘higher concerns’ |

Discussion

In dealing with the physical injuries, you may need to seek help from a trained professional, or if you are acting as an educator you should be able refer to a first aider in your workplace.

Speaking to the young person, it will be important to draw on some active listening skills. Remember that you worked on these in Session 6.

It may be necessary to urgently identify other professionals you could make contact with.

Confidentiality is clearly important to many young people but it is important to know that for educators, your school will have policies about how you should handle sensitive information and were responsibilities lie in regard to safeguarding.

The circumstances and potential risks can be wide ranging, and these serious judgements need to be made in discussion with others.

While a flow chart is useful in providing a clear checklist of the actions that might be useful when a young person reveals they have been self-harming or displaying other behaviours of concern, it can be hard in the moment to know how to respond as one human to another. You will consider this in the next activity.

1.2 Self-harm

In this activity we ask you to put yourself in the position of the practitioner who is listening to a young person who is revealing they have been self-harming. The young person has shown you the scars and starts to cry.

Activity 3: Responding to self-harm

2. Now, watch the video and make a note of the main messages that are suggested for guiding a professional response to this type of disclosure. Consider the skills and characteristics a practitioner would need to demonstrate in order to support the young person effectively.

Discussion

Skills you might have identified include:

- observation skills

- Through noticing injuries or behaviour changes, a parent or practitioner may become aware of a problem and ask the young person or their child if they would like to talk.

- listening skills

- The young person should be the sole focus of attention.

- relationship building skills

- While a parent can build upon an established relationship, a practitioner needs to build trust, whilst not making unrealistic promises about confidentiality.

- teamworking skills

- A young person may feel comfortable talking to one particular practitioner and may need help from many people, including family, peers and other practitioners.

- skills around protecting the parent and/or practitioner’s own wellbeing.

- This work can be challenging, so it is important to be supported and to seek support or take up training opportunities where needed. It is important not to keep any uncomfortable feelings about any disclosures to yourself.

Characteristics for both parents and practitioners that might be helpful include:

- being supportive and accepting

- being non-judgemental

- being calm.

Although it is not mentioned in the video, helping young people find practical alternatives to self-harm, such as making a self-soothe box (a collection of things that will soothe or distract) could also be a useful option. You will recall Dr Pooky Knightsmith in Session 6 talking about the importance of self-soothing.

2 Talking therapies

Mental health campaigns such as ‘#oktotalk’, ‘#Take20’ and ‘#TimeToTalk day’ reinforce the idea that talking about mental health is a positive step in accessing help and improving wellbeing. You will also recall one of the parents introduced in Session 4, talked about how therapy proved exceptionally helpful for her daughter in dealing with depression and anxiety. As the name might suggest, ‘talking therapies’ harness the healing power of talking and being listened to, helping someone to improve their mental health. They usually involve a trained therapist who can help the young person to manage and respond to their feelings of distress. Importantly, talking therapies also offer young people strategies for changing the way they think about their feelings and their responses to events. This can help them to develop good practices for the future and help them to learn vital life skills. It is possible to access NHS psychological therapies service directly (IAPT) without a referral from a GP.

Talking therapies take many forms and the key thing to note is that some talking therapies may suit some type of problem and individual more than others. The experience of talking therapies is highly personal and it can take time to find the most helpful approach. The main talking therapy recommended for adolescents is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, or CBT. CBT is accepted as an effective first-line treatment in adolescent mental health (Halder and Mohato, 2019).

2.1 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Talking therapies, especially CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy), can be useful in a range of mental health problems, for example depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. You will recall one of the parents talking about her daughters mental health in Session 1 and how she benefited from CBT. Although CBT is usually conducted face-to-face on a one-to-one basis, it is increasingly offered online, usually as an adjunct to appointments with a therapist, and has been found successful (van der Zanden et al., 2012; Spence et al., 2011).

The idea behind CBT is that a young person is helped to examine and to challenge the way they think as well as what they do. Thoughts, emotions, physical symptoms and actions (behaviour) interact in all directions. Briefly familiarise yourself with the diagram below and then move on to the activity.

Activity 4: Making sense of CBT

Imagine that a young person you are caring for or supporting has been referred for CBT. They don’t think talking will help and complain that they don’t want to ‘lie on a couch discussing their dreams’. Watch this video and make a note of some of the things you can say to help address their concerns and convince them to give therapy a go.

Transcript: Video 2: What is CBT? | Making Sense of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Discussion

It’s about helping a person to manage their mental health challenges while staying in the present, and teaching coping skills. It can help the young person understand how their negative thoughts are affecting the way they feel and act. If CBT turns out to be unhelpful, there is no shame in asking to try alternative approaches.

A key skill for CBT practitioners is active listening. You will remember addressing skills in listening in Session 6. You may have noticed in the video that the therapist’s questions follow closely from the patient’s descriptions of his feelings, gently prompting exploration of his beliefs. CBT therapists need to listen carefully and attentively so that they can ‘tune in’ effectively to the patient.

2.2 The importance of professional help

The following activity will take you through an example of how seeking professional help can really improve some people’s mental health.

Activity 5: Understanding the importance of professional help

In the first clip John Goss, a professional counsellor talks about the issues he listens to when a young person comes to see him.

Transcript: Video 3: John Goss and the issues young people face.

Now listen to the following audio and make a note of the things that this mum found to be important about her families work with a professional therapist.

Transcript: Audio 2

Answer

John stresses that within the counselling room it is possible for young people to describe things that they may be hiding from others as they attempt to ‘look fine’ on the surface. This mum initially describes the importance of one the techniques they were taught to use with their daughter as part of the CBT, this was called ‘worry time’ and it was a period of time fenced off from the rest of the day in which they would discuss with their daughter any ongoing concerns she had. But she also highlights how crucial the therapist was in highlighting the progress steps that she was making, and how this was taking her through to recovery. It was this progress that helped the family see what the therapist described as the ‘green shoots’ and how things were improving.

A therapist will find ways of intercepting and challenging the relationships between thoughts, feelings and behaviours so that different thought patterns are created and reinforced. By encouraging reinterpretation of a young person’s responses to certain triggers, the practitioner can help to break the cycle of unhelpful responses. If CBT doesn’t work, there are other types of therapy available such as person-centred counselling. You can find out more about these different types of therapy via the NHS website.

Sometimes other forms of treatment are needed. You will learn more about medical interventions in the next section.

3 Medical interventions

The first line of treatment offered nowadays will in many cases involve ‘talking therapies’. However, in some cases medical interventions may be offered for mental health problems. These typically comprise different types of medication such as anti-anxiety medication and anti-depressants. The next activity asks you to consider what you already know about antidepressants for young people.

Activity 6: Understanding the role of anti-depressants

Below is a list of statements relating to antidepressants. For each statement, decide whether it is true or false.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Answer

False: The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) warns against using St John’s wort for the treatment of depression in children and young people.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

Answer

True: see the NICE guidelines.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Answer

False: Fluoxetine is often the first line of treatment when drugs are deemed necessary.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

Answer

True: The risk of suicide is greatest in the early stages of treatment. This may be due to the fact that the drugs need to be taken for a few weeks before they become effective in treating depression (which is itself associated with an increased risk of suicidal behaviour). Firm explanations are still being sought. Source: Gov.uk

3.1 Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

You may have heard the acronym SSRI, which stands for Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor. Fluoxetine is a type of SSRI, and it works by raising the levels of serotonin in the brain. According to the NHS (2018):

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter (a messenger chemical that carries signals between nerve cells in the brain). It’s thought to have a good influence on mood, emotion and sleep.

After carrying a message, serotonin is usually reabsorbed by the nerve cells (known as ‘reuptake’). SSRIs work by blocking (‘inhibiting’) reuptake, meaning more serotonin is available to pass further messages between nearby nerve cells.

It would be too simplistic to say that depression and related mental health conditions are caused by low serotonin levels, but a rise in serotonin levels can improve symptoms and make people more responsive to other types of treatment, such as CBT.

You can see that the use of SSRIs is firmly based in the biomedical approach introduced in Session 4, drawing on knowledge of neuroscience and finding a drug that has the potential to ‘fix’ a problem in the body. The NHS information extract also pointed out that the situation is not as simple as saying low serotonin is a cause of mental health problems. Mental health is the product of a complex interaction of biological, psychological and social influences, and serotonin is one small part of a big jigsaw.

In most areas of health, and particularly mental health, it is rare to identify a single ‘cause’ of illness. It is important to appreciate this complexity and not to jump to conclusions about the source of a problem, nor what should be done to help. Anti-depressants can be a big taboo and you will learn more about their benefits in the next activity.

Activity 7: Hannah’s mental health story

It is important to know when anti-depressants may be useful for some young people. Watch this video and consider the reasons that Hannah describes that underpinned her decision to take anti-depressants.

Transcript: Video 4: Hannah’s Mental Health Story

Discussion

Hannah talks a lot in her video, initially about all the efforts she made to improve her mental health. She described getting exercise, sleep and eating right as helpful and her engagement with professionals who provided talking therapy. But she also points out that this had a limited impact and that eventually she became aware that therapy wasn’t enough – she came to accept that she needed anti-depressants. It was a huge step for her to take them and she felt it was taboo to say she needed to take them. She shares the story because she wants people to know that it has changed how she feels about how she wakes up in the morning. In summary her message is that if you have tried everything else and if your mood is not getting better, then medication might provide some additional help.

4 Making referrals

If you have been working with children for some time, or if you are familiar with mental health services for adults, you may have heard the word CAHMS used in relation to service provision. In most areas of the UK, Child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) are commissioned to work with children and young people up to the age of 18 who are experiencing emotional or mental health problems. It is not possible for a young person or their parents to self-refer, and there are a number of reasons for this. One of the main being that professionals working in primary care and schools, such as GPs, school doctors and nurses, educational psychologists, special educational needs coordinators and social workers are often best placed to provide initial help. They tend to be based in the young person’s community and can draw on their professional networks to organise support around the needs of the young person and their family. CAMHS take over when the practitioners with more generalist skills identify the need for specialist care, e.g. prescribing medication, advanced therapy skills and specialist skills aligned to particular mental health issues. These practitioners based in local communities are essentially the ‘gatekeepers’ for the more specialist CAMHS.

CAMHS is typically represented by a tier structure. Tier 1 represents ‘universal’ services with a remit to promote good mental health. Tier 2 represents more targeted services that can support young people with the less severe problems. Tier 3 is the beginning of the specialist services that deal with more severe needs, usually on an outpatient arrangement. Tier 4 is highly specialist and often involves a hospital stay (ACAMH, 2020). Click through the tabs to read an explanation of each of the tiers.

Revisiting the ‘mental health spectrum’ introduced in Session 2 and considered again in Session 6, a young person would need to be ‘struggling’ and moving into the ‘unwell’ zone for a referral to specialist services.

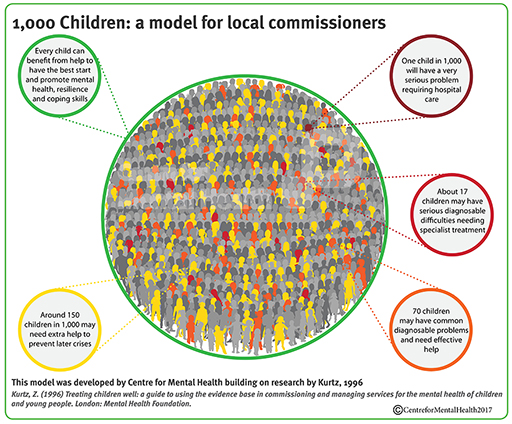

To put things into perspective, look at this infographic developed by the Centre for Mental Health (2017). Based on 1996 research, the figures will not be quite up to date. They do, however, provide a sense of proportion, based on a population of 1000 children and young people, about the levels of support likely to be needed at any one time.

As this infographic highlights, at any one time, out of 1000 children and young people:

- about 150 have a high risk of poor mental health and may need extra help to prevent later problems;

- a further 70 will have a common diagnosable problem for which they need effective help;

- 17 will have a serious problem needing specialist treatment;

- one will have a very serious condition that requires hospital care.

It also illustrates the complexity of mental health and the importance of exploring the referral process in order to receive the most appropriate support and treatment. You will explore this next.

5 Seeking guidance

GPs have to be selective in their referrals to mental health services. At the time of writing, pressures on CAMHS are high in the UK and GPs have been finding that more than half their referrals to CAMHS are rejected. For those whose referral is accepted, it is not uncommon to wait between 3 and 12 months for a CAMHS appointment (Bostock, 2020). Young people who are referred for eating disorders and psychosis are usually given priority (ACAMH, 2020).

Activity 8: What can you do if you are on a waiting list for specialist support?

While you are waiting for professional help it can be hard to know what to do. Our interview with counsellor John Goss revealed some things that he thought you could do to support yourself or someone you care for. Make some notes as you watch Video 5.

Transcript: Video 5: Waiting for professional help

Discussion

John describes simple activities as being effective in providing self-care. For example, walking, reading or writing a diary can be a positive way of challenging thoughts. These are simple but positive ways of supporting the young person, but they also provide a way to prepare for therapy when it does commence.

If you find there is a long waiting time on the NHS you may wish to seek alternative sources of help, for example charities sometimes offer advice that can be accessed straight away. If you have funds available to pay for counselling, it is also possible to access private therapy. Many people don’t know where to start in finding counselling for themselves or someone else. Many people find the best way to find a therapist or counsellor is through word of mouth. For example, if you know someone who has already accessed private therapy you might wish to ask them for a recommendation.

Given the sensitive nature of the counsellor relationship, it is important to ensure that the person you reach out to is appropriately qualified. To assist in this the various professional counselling bodies have set up directories of their members that can be accessed via their websites. Examples include those linked to below:

6 This session’s quiz

Now it’s time to complete the Session 8 badge quiz. It is similar to previous quizzes, but this time instead of answering five questions there will be fifteen.

Session 8 compulsory badge quiz

Remember, this quiz counts towards your badge. If you’re not successful the first time, you can attempt the quiz again in 24 hours.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window then come back here when you’ve finished.

7 Review the journey

You have now reached the end of this course. We have covered a lot of ground over the past eight sessions and are aware that it is impossible to cover everything that you might need to know in order to provide support to a young person who is experiencing mental health issues. Our intention here has been to give you a sound introduction to these issues and to help you develop tools which can help you gain the confidence to support young people and to recognise where you can go to find further help.

In the words of one young person experiencing OCD: ‘It’s a battle everyday and during its worst every single thing that I have done took decision making fighting between voices in my head and my own. It can take hold and feel like you can’t control yourself. It’s confusing because it’s not a rational thing. It’s a very difficult thing to describe and I do believe it’s different for everyone – like everyone’s brains. Something I think it’s useful for people to understand is that everyone has struggles and people’s mental health is different and to try and be less judgemental of anyone with mental health as everyone’s behaviour stems from a place of reason. And mainly to support people you don’t have to be perfect you just have to be kind and willing to try your best. We all learn as we go and no one is perfect so if someone is supporting someone with mental health in particular OCD it’s ok to not be perfect – being kind to yourself so you can understand others too.’

As our final activity we want to remind all those who support young people of exactly what young people think about mental health support and what would work for them. With this in mind watch this video, produced in conjunction with young people.

This video supports many of the messages from across this course, it notes pressures on young people to succeed and issues relating to social media. In relation to the help they wanted, it was reported that they wanted authentic communication that does not infantilize them, tell them it is just a phase, and which does not overly generalise about their experiences. They want personalised care, with more care choices and different types of care offered in a variety of settings. However, as the video also suggests they are aware that waiting times are an issue.

Education and communication remain central to changing our approach to mental health challenges. Throughout this course you have been introduced to a lot of ideas about mental health and how to support a young person who may be struggling with their emotions. The most important thing you can take away from this course is to listen emphatically to the young people you are caring for. Therefore we believe it is fitting to end this course with a clip from one of the young men we interviewed which reminds us of all the things that young people are coping with as they transition this difficult but exciting time of life.

Transcript: Video 7: Gets real very quickly

Where next?

New to University study? You may be interested in our courses on health and wellbeing.

Making the decision to study can be a big step and The Open University has over 40 years of experience supporting its students through their chosen learning paths. You can find out more about studying with us by visiting our online prospectus.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Victoria Cooper, Sharon Mallon and Anthea Wilson and was published December 2021. We would also to thank Jennifer Colloby, Steven Harrison and Karen Horsley for their key contributions and critical reading of this course. We would like to thank the parents, young people and professionals who shared their experiences with us.Their willingness to share sensitive and highly personal accounts of having or supporting those with mental health challenges adds greatly to this course and we will hope will benefit all those who find themselves in similar situation.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below (and within the course) is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Session 8: Seeking expert support and accessing services

Figures

Figure 1: adapted from: https://mindedforfamilies.org.uk/ Content/ who_can_help_us/ #/ id/ 5e30a7a17c501d4bd0554a83 MindEd For Families

Figure 2: from: Young people who self-harm A Guide for School Staff (p15) b5791d_b3807e6a2cd643ed8b29456602afcc01.pdf (wixstatic.com) Developed by Researchers from The University of Oxford © University of Oxford

Figure 3: adapted from SilverCloud & Blended Online CBT SilverCloud & Blended Online CBT – Mid & North Powys Mind (mnpmind.org.uk)

Figure 4: adapted from The CAMHS four tier structure adapted from https://www.icptoolkit.org/child_and_adolescent_pathways/about_icps/camh_service_tiers.aspx © Healthcare Improvement Scotland 2012.

Figure 5: Centre for Mental Health 2017 https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/

Figure 6: Centre for Mental Health 2017 https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/

Audio/Video

Video 2: Video 2: What is CBT? | Making Sense of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Courtesy: © Mind Home | Mind, the mental health charity - help for mental health problems

Video 4: Hannah’s Mental Health Story Courtesy: ©Mind https://www.mind.org.uk/ https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=gn0F36WvLA8

Video 6: What kind of mental health support do young people want? Healthwatch. https://www.healthwatch.co.uk/ Open Government Licence (nationalarchives.gov.uk) https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=SOxKM1yimpo

Video 7: Gets very real very quickly © The Open University

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – The Open University.