Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 1:21 PM

Session 3: Different dimensions of adolescent mental health

Introduction

Mental health becomes a problem when it interferes with daily life.

Although individuals vary, there are certain signs and behaviours that can signal that a young person is struggling with their mental health and in this session you’ll learn about some of them. Mental health depends on social, emotional and psychological wellbeing. The causes of mental health problems are often a combination of biology (how the brain and body work, especially in response to stress), psychological traits (e.g. personality type), the social environment (life experience), and sometimes certain chemical substances (such as alcohol or marijuana). A tendency to develop mental health problems can run in families, although the reasons for this are complicated and may include inequalities and poverty that run between generations. There is still a great deal of debate among researchers about how these factors interact. However, most experts now agree that there is rarely a single cause.

To get started on understanding some of the different dimensions that can affect mental health, watch the video, which features a group of young people describing their own experiences of mental health problems.

Transcript: Video 1: Mental health in our own words

This session will introduce you to four sets of common mental health problems, starting with anxiety and depression. Anxiety and depression are commonly used terms, and you will get below the surface to discover what they mean. Anxiety and depression can sometimes develop into other behaviours such as eating disorders and self-harm. On your journey through this session, you may encounter material that can be unsettling, although we hope that the knowledge and understanding you gain will help you to become a more effective supporter of young people who are struggling with their mental health. If you are affected by any of the course material please refer to our support notes at the end of this session.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this session, you should be able to:

describe some of the characteristics of a range of mental health problems

recognise the potentially unhelpful behaviours that can arise with mental health problems

identify measures that enable you to help young people who are experiencing mental health problems.

Some conditions are not covered here, for example, bi-polar disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and schizophrenia, including auditory hallucinations and substance abuse. You can find links to information about these conditions in the Further reading section.

1 When does mental health become ill-health?

According to the World Health Organization, ‘Mental disorders comprise a broad range of problems, with different symptoms. However, they are generally characterized by some combination of abnormal thoughts, emotions, behaviour and relationships with others’ (WHO, n.d.).

There may be no clear dividing line between a situation where a young person is coping well with challenges, to a point where they struggle or become mentally unwell. As you can tell from the video you watched in the session introduction, problems with mental health can unfold gradually to a point where the young person and the people around them realise they have a serious problem. In the next activity, you’ll revisit the video and consider where to place these young people on the mental health spectrum.

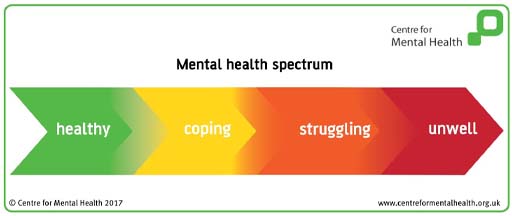

You first saw this spectrum in Session 2. At the green ‘healthy’ end, there would be no particular cause for concern, except to ensure that the young person has the support and skills necessary to deal with everyday life. In the yellow ‘coping’ zone, the young person may be experiencing difficulties and need extra help to prevent any problems developing further. In the orange ‘struggling’ zone, the problems may become more visible and it is possible a diagnosis of a mental health problem will be made. An ‘unwell’ young person who has a very serious problem may need highly specialised help.

Activity 1: A spectrum of mental health

Think about the mental health spectrum in Figure 2 and consider each of the case studies below of young people who are experiencing emotional challenges. As their stories progress, think about where they would be on the spectrum.

Case 1: Jack

Jack had surgery and found it really difficult to play sport and go out with his friends, he found it really hard to cope with this. He became really sad and spoke to a teacher at school who tells him he needs to pick himself up and get on with it. But then as he continued to struggle to get to sleep, he then started to find it hard to get up in the morning and struggled to concentrate in lessons. He finally got help when he refused to go to class.

Case 2: Suzie

Suzie is shy and got bullied at school as a result. This really affected her self esteem and confidence. It also started her worrying when speaking in groups. This kicked off anxiety and she found it hard to enter particular classrooms where she knew the bullies were – she started missing these classes.

Case 3: Bob

Bob started questioning their gender identity from the age of 15. This became a big problem when they shared it with a friend who then broke their confidence and now the whole of her class know. They started to self harm and found they woke up in the middle of the night and could not get back to sleep. Their swim teacher noticed the marks on their arm were bleeding and reports it to her mum.

Discussion

The spectrum can be a useful tool for understanding the varying nature of mental health. Although mental health problems are very particular and personal to the individual, their experience also takes place within the context of wider social and environmental influences. As you can see from these case studies, each of the young people moved through a range of emotions, and that recognising the difference and the point at which it was interfering with their life was crucial and reflected when the adults around them recognised there was a need for a solution.

Although mental health problems can sometimes make people feel trapped in cycles of unhelpful thoughts, feelings and behaviours, it is important to realise that with the right help solutions can be found. Going forward in this course, you’ll come across many examples of how family and friends as well as professionals can help young people.

Everyone has set-backs that can make them feel low, sad or anxious. However, we often know when all is not as it should be, and the next section considers when anxiety becomes a problem.

2 Anxiety

Anxiety is a normal response to situations that may threaten wellbeing. Signs of anxiety usually include feelings of being frightened, worried, nervous or panicky, and these feelings can be useful if you need to respond to a threatening situation.

It is perfectly normal to feel anxious before an exam, the results of which can determine future opportunities. It is also normal to feel anxious in an encounter with a growling dog, which could pose a threat to your physical safety. Many of us will empathise with the feelings of anxiety that can be heightened during a viral pandemic that also pose real threats.

If anxiety persists, young people may have difficulties sleeping, eating and being able to concentrate. When anxiety becomes a more generalised feeling that interferes with everyday life over a lengthy period, it is no longer a useful feeling and it can become a mental health problem. In the next activity, you’ll read about Kim who is having a problem with anxiety.

Activity 2: Kim’s anxiety

Read the case of Kim, who is experiencing problems with anxiety. Then, jot down some notes in response to the following questions:

- Which aspects of Kim’s experience might lead you to believe she is ‘struggling’ rather than ‘coping’ with anxiety?

- Are there any aspects of her experience you might consider ‘normal’?

- What makes it difficult to decide?

Kim, who is 15, feels stressed and exhausted all of the time, sleeps badly, and has frequent headaches. She worries persistently about her schoolwork. Each morning on a school day, she gets a ‘nervous tummy’ and sometimes she stays off school because of this. The problem started a couple of years ago when her parents were having terrible rows, at which point she felt incapacitated with anxiety. Since then, her parents have split up and she now lives with her grandparents.

Discussion

- Signs that Kim is ‘struggling’ include her exhaustion, headaches, taking time off school with minor symptoms. Her worries about school work, which could be normal for many, sound as though they are becoming a problem that she cannot resolve alone.

- Kim’s ‘nervous tummy’ is a common experience for many people, young and old when feeling excited or challenged by a situation. Perhaps in her anxious state she is interpreting it as a bad thing rather than recognising its power simply to signal that she is facing a challenge.

- Everyone faces anxious situations, and problematic anxiety develops over time, so the whole picture is important when deciding whether anxiety is a problem.

Feelings of anxiety may follow life events and certain trigger experiences. For many, although not all young people, learning how to regulate and manage their feelings can be helpful. Session 6 will introduce ways of helping young people.

3 Depression

Depression, thought of as a problem with low mood, is generally a feeling of sadness accompanied by a sense of hopelessness, emptiness, and the loss of interest in things one used to enjoy.

Young people who are depressed are more likely to be irritable or show aggression than adults with depression. They may also refuse school, perform progressively less well in education, and isolate themselves from family and friends (Roberts, 2013). Young people with depression often find it difficult to sleep, or perhaps feel sleepy or tired for large parts of the day. They may express feelings of worthlessness or guilt, and find it difficult to concentrate. You may also notice changes in their appetite.

Activity 3: Elliott’s depression

Read this case of Elliott, who is experiencing depression:

Elliot, who is 16, has had difficulty sleeping in the past few months and is frequently tired. He has been spending more time alone and, despite complaining of boredom, has little energy or desire to go out with his friends. His parents have noticed that he has been much more irritable than normal and that he doesn’t seem to be doing much homework these days. When asked about these changes, he says he feels worthless and that nobody likes him.

- Which aspects of Elliott’s experience might lead you to believe he is ‘struggling’ rather than ‘coping’ with his low mood?

- Are there any aspects of his experience you might consider ‘normal’?

- What makes it difficult to decide?

Discussion

- Signs that Elliott is ‘struggling’ include his tiredness and poor sleep over several months. Also, he seems to have stopped socialising. Expressing his worthlessness and low self-esteem is a clear sign he is struggling.

- Elliott’s irritability and lack of homework might be explained by something that happened at school that is upsetting him, which could be thought of as a ‘normal’ response.

- It can be difficult to decide, partly because it is common for adolescents to feel tired in the mornings if they are adjusting to the changes in their body clock, and Elliott’s irritability might be taken to be normal teenage behaviour, but it could also be part of his depression. As with Kim’s case, the key to identifying a struggling young person would be to notice a combination of factors over a length of time.

Many of the signs of anxiety and depression can look similar, and it will help to talk to a young person you are concerned about. You’ll explore ways of encouraging a young person to talk in Session 6. The next section explores eating disorders, which can sometimes arise when a young person is depressed or anxious.

4 Eating disorders

Eating disorders most commonly start in the mid-teens and can become serious illnesses.

In economically advanced countries, it is estimated that the proportion of adolescents and young adults experiencing eating disorders is approximately 3% (30 in a thousand) females and 0.1% (one in a thousand) males. It is easy to underestimate the amount, however, because not everyone seeks help and it can be difficult to conduct surveys that are truly representative of a community (AYPH, 2019).

According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), an eating disorder is when you have an unhealthy relationship with food which can take over your life and make you ill. It might involve eating too much or too little, or becoming obsessed with controlling your weight (NICE, 2017, p. 2).

Eating disorders can be a way of coping and/or expressing emotional distress. Causes of eating disorders are varied and are thought to include:

- low self-esteem, depression or anxiety

- family history of eating disorder and inherited genes

- relationship difficulties, peer pressure to be thin or bullying (Bould et al., 2017).

A young person with anorexia nervosa, for example, becomes preoccupied with weight and body shape and tries to lose weight by restricting food intake, exercising, inducing vomiting or using laxatives. Limiting food intake can be a way of feeling in control and coping with life but the young person can also feel as though the illness controls them. It is common to deny weight loss, have an extreme fear of gaining weight and resist offers of help.

In the next activity, you’ll hear about three types of eating disorder.

Activity 4: Dealing with an eating disorder

Watch this video, a cartoon-style explanation of different eating disorders.

Transcript: Video 2: Different eating disorders

Pick out three common themes relevant to all the types of eating disorder mentioned in the video: Anorexia nervosa, Bulimia nervosa, and Binge eating disorder.

Discussion

Here are three themes that can be picked out:

- Obsession with body shape and food intake.

- A sense of control or lack of control over eating.

- Being secretive about eating.

You may also have noticed the warning signs to look out for, such as noticeable weight loss, feeling tired and cold, eating very fast or very slowly, frequently going to the bathroom after eating, and excessive exercising.

4.1 Early intervention

Early intervention in the case of an eating disorder makes a substantial difference in reducing the ongoing distress and improving outcomes. In Figure 6, you’ll see figures from a survey conducted by the UK charity BeatED in 2017, which shows that it took on average 69 weeks before recognising a young person had an eating disorder and it took a further 39 weeks before the young person sought medical help.

Reasons for the initial delays vary. The next activity helps you to consider some of these.

Activity 5: Reasons for a delay in seeking help for an eating disorder

a.

Perceived stigma of mental health problems

b.

Family tensions making communication difficult

c.

Not realising the problem is serious

d.

Not knowing what to say or how to say it

e.

The young person is good at hiding their problem

f.

Lack of information about eating disorders

g.

Denial of the problem

h.

Most people are already well informed and know how to deal with an eating disorder

The correct answers are a, b, c, d, e, f and g.

Discussion

Did you realise that they could all apply except for ‘Most people are already well informed and know how to deal with an eating disorder ‘?

Eating disorders can create tensions and guilt in families and parents may find it difficult to help effectively (Eklund and Salzmann-Erikson, 2016). An interesting study of South Asians living in the UK found that they:

- worried about the stigma associated with mental health

- thought eating disorders could be easily fixed

- worried about privacy and confidentiality within their communities

- warned that these issues were not confined to this ethnic minority.

(Wales et al., 2017).

There is also some evidence that 16-25-year-old males do not recognise an eating disorder in themselves because they consider it a female problem (Räisänen and Hunt, 2014) and that this is a stereotype entrenched in the media (Maclean et al., 2015).

Early identification is important in all mental health problems and it can sometimes prevent the development of unhealthy behaviours such as self-harm, which you will consider next.

5 Self harm

Similar to eating disorders, self-harm is an expression of emotional distress. People who self-harm tend to use it as a coping strategy for handling intense feelings such as anger, distress, fear, worry, depression or low self-esteem (SelfharmUK, 2020a and b). Have a look at the statement from the Royal College of Psychiatrists:

Self-harm happens when you hurt or harm yourself. You may:

- take too many tablets – an overdose

- cut yourself

- burn yourself

- bang your head or throw yourself against something hard

- punch yourself

- stick things in your body

- swallow things.

It can feel to other people that these things are done calmly and deliberately – almost cynically. […]Some of us harm ourselves in less obvious, but still serious ways. We may behave in ways that suggest we don’t care whether we live or die – we may take drugs recklessly, have unsafe sex, or binge drink. Some people simply starve themselves.

Activity 6: Reactions to self-harm information

a.

Difficult to fully grasp.

b.

It must be attention seeking behaviour.

c.

I know someone who has done this.

d.

Perhaps they don’t feel the pain like others do.

e.

I wouldn’t know how to help someone with this problem.

The correct answers are a, b, c, d and e.

Discussion

Some people have described self-harm as a way to express something that is hard to put into words; to reduce overwhelming emotions or thoughts; a means of escaping traumatic memories; a way to communicate to other people that you are experiencing severe distress; and/or to have a sense of being in control. As you will see in the next activity, the physical pain is real and self-harm is rarely a deliberate ‘attention-seeking’ act.

According to the charity Young Minds, self-harm affects up to 1 in 5 young people. An analysis of medical records has indicated that instances of self-harm are rising (Morgan et al., 2017). Self-harm is mainly done in private and is often hidden, and it is a very sensitive topic, so the reliability of data about young people who self-harm has to be considered carefully. For example, has there been a genuine increase in self-harm over the past few decades, or merely more reporting, help seeking and acknowledgement of the issue?

The charity YoungMinds has written a summary of warning signs for self-harm:

There are many signs you can look out for which indicate a young person is in distress and may be harming themselves, or at risk of self-harm, the most obvious being physical injuries in which:

- you observe marks on more than one occasion

- they appear too neat or ordered to be accidental

- the marks do not appear consistent with how the young person says they were sustained.

Other warning signs include:

- secrecy or disappearing at times of high emotion

- long or baggy clothing covering arms or legs even in warm weather

- increasing isolation or unwillingness to engage

- avoiding changing in front of others (may avoid PE, shopping, sleepovers)

- absence or lateness

- general low mood or irritability

- negative self-talk – feeling worthless, hopeless or aimless.

‘At first we thought he was just accident prone, it was easy to miss, he always had an explanation as to how he’d got hurt.’

You will see some similarities with other mental health problems such as eating disorders, and it is important to realise that the accumulation of signs should raise warning signals.

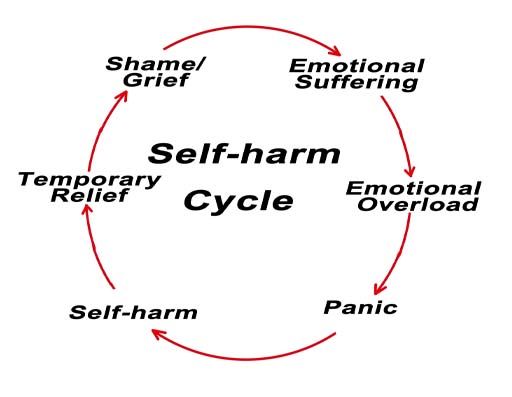

5.1 Breaking the self-harm cycle

Self-harm is an expression of emotional distress, or of relief of unbearable tension and a sign that something is seriously wrong – it can also be an attempt to communicate internal distress and a need for help. For these reasons, and because of the physical damage people may inflict on themselves, witnessing self-harm in someone you care for or about can be distressing. It can also be puzzling, trying to understand what drives a person to hurt themselves in these ways. If, however, a young person is brave enough to seek help in relation to these behaviours, this should be considered an act that has taken courage and needs a sensitive response.

There are no clear-cut explanations about why people begin to self-harm. Reasons that have been put forward include a reaction to specific difficult or unpleasant experiences, and a way of dealing with something that is happening now or that happened in the past. Other common reasons suggested are:

- bullying

- difficulty at school

- sexual, physical or emotional abuse

- failure of relationships (Smith, 2013, p. 5).

Given the highly individual nature of this type of act, it is important not to make too many assumptions. The next activity will help you to consider these issues further.

Activity 7: Understanding the self-harm cycle

Watch the video ‘Understanding and breaking the self-harm cycle’ presented by Child and adolescent mental health expert Pooky Knightsmith.

Transcript: Video 3: ‘Understanding and breaking the self-harm cycle’ presented by Child and adolescent mental health expert Pooky Knightsmith.

If you know someone who is self-harming, make a note of one or two things you might be able to do to begin breaking the cycle.

Discussion

Understanding how a young person can get stuck in the self-harm cycle is a good starting point. Act as early as possible, remembering that talking about the problem is a good thing. Also, exploring ‘healthy’ coping strategies as alternatives to self-harm may be helpful. You may have picked up early in the video that telling someone to stop can be unproductive in the absence of effective coping strategies to replace the self-harm. It is also important to reassure a young person that they can step out of this cycle of self-harm and even though they may revert to these behaviours during difficult times, with help and support they can find healthy coping strategies.

If you are interested in more detail about how to help, see the further reading section.

Sadly, young people who self-harm are more likely than average to contemplate suicide. The next section will deal briefly with this difficult topic.

6 Suicide

Young people face many challenges growing up. You will have already noted that adolescence represents a period of considerable physiological and psychological change, which brings with it new opportunities and experiences. This can be both daunting and exciting and yet as the Mental Health Foundation (2003) stress, for some young people these emotional challenges can be too much to bear.

Suicide is rare at any age and is often undertaken as a last resort in response to emotions, problems and challenging circumstances that overwhelm an individual. It is particularly associated with feelings of hopelessness that things will never get better and a feeling of a lack of control over the future.

The latest available UK figures (at the time of writing) show that in the age group 10-14, the suicide rate is 0.4 per 100,000 and in the 15-19 age group it is 6.7 per 100,000. The highest suicide rates occur in the age group 45-49 (18.1 per 100,000). Suicide is considerably more common in males than in females (ONS, 2019).

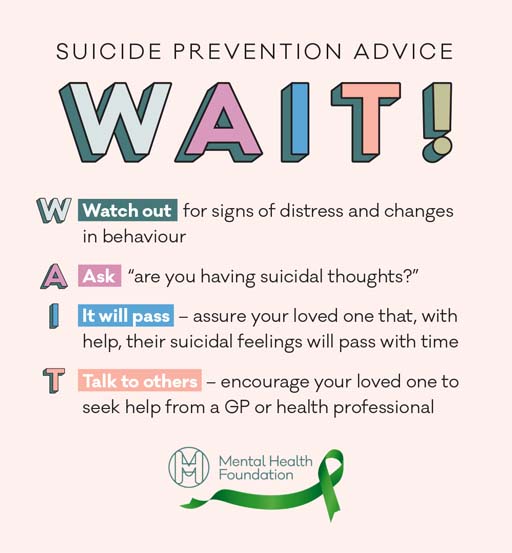

If you have studied the course up to this point, you’ll already have some understanding of the emotional challenges for adolescents. In particular, young people may struggle with self-esteem issues and self-doubt. As with all mental health problems, the key to helping is to start a conversation. The infographic in Figure 8 summarises how to help using the WAIT acronym shared by the Mental Health Foundation:

An important message to take from this advice is that directly asking a young person about whether they are having suicidal thoughts will not increase the likelihood of suicide. Contrary to the fears of many, asking about suicide ‘can start a potentially life-saving conversation’ (Mental Health Foundation, 2020). Talking to a young person and encouraging them to share their concerns is vital and will enable you as a parent, carer or practitioner working with young people to seek specialist guidance and support.

If you are concerned about a young person who is showing signs of distress, disclosing their thoughts about suicide or eliciting changes in their behaviour there are avenues of support available to you. If a young person shares suicidal thoughts or feelings with you, it is important that you take them seriously and seek guidance about how to best support the young person and to protect them from undertaking actions which may cause their death. It may be helpful to talk to their carers or parents. Or if you are their parent or guardian talking to the GP about these disclosures will help you to plan what you need to do. Other immediate sources of help include:

- Samaritans offer a 24-hours a day, 7 days a week support service. Call them FREE on 116 123. You can also email jo@samaritans.org

- Papyrus is a dedicated service for people up to the age of 35 who are worried about how they are feeling or anyone concerned about a young person. You can call the HOPElineUK number on 0800 068 4141, text 07786 209697 or email pat@papyrus-uk.org

- NHS Choices: 24-hour national helpline providing health advice and information. Call them free on 111.

7 This session’s quiz

Check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you’ve finished.

8 Summary of Session 3

The main learning points of this session are:

A helpful way of thinking about mental health is that it exists on a ‘spectrum’ representing anything from healthy functioning through ‘coping’ and ‘struggling’ to becoming ‘unwell’. People can move along this spectrum in both directions.

Anxiety and depression are emotional responses to life’s challenges, in which a young person begins to find it increasingly difficult to cope and may be struggling. Listening and encouraging the young person to talk about their difficulties is an important first step in helping.

Eating disorders and self-harm can become habitual ways of coping with emotional distress. Recognising these problems at an early stage can mean the young person receives professional help sooner. Parents, teachers and other caregivers can all play a role in breaking the cycle of harm.

There is risk of suicide in young people who are struggling with their mental health, and the WAIT! Suicide prevention advice can help you to intervene if you are concerned about someone.

Finally, listen to Tanya Byron summing up some of the issues you have considered in this and the previous sessions.

Transcript: Audio 1: Interview with Professor Tanya Byron

Now go to Session 4.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Victoria Cooper, Sharon Mallon and Anthea Wilson and was published December 2021. We would also to thank Jennifer Colloby, Steven Harrison and Karen Horsley for their key contributions and critical reading of this course. We would like to thank the parents, young people and professionals who shared their experiences with us.Their willingness to share sensitive and highly personal accounts of having or supporting those with mental health challenges adds greatly to this course and we will hope will benefit all those who find themselves in similar situation.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below (and within the course) is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Session 3: Different dimensions of adolescent mental health

Text

Text extract from Young Minds p3 (2020) No Harm Done: Recognising and responding to self-harm. Available at https://youngminds.org.uk/ resources/ school-resources/ responding-to-self-harm-guide/

Figures

Figure 1: CRISTINA PEDRAZZINI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Universal Images Group

Figure 2: ©Centre for Mental Health 2017 https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/ mental-health-among-children-and-young-people

Figure 3: LOUISE WILLIAMS/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Universal Images Group

Figure 4: PAUL BROWN/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Universal Images Group

Figure 5: PAUL BROWN/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Universal Images Group

Figure 6: courtesy: beateatingdisorders.org.uk https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/ uploads/ documents/ 2017/ 11/ delaying-for-years-denied-for-months.pdf)

Figure 7: arka38/Shutterstock.com

Figure 8: Courtesy: Mental Health Foundation https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/ publications/ suicide-prevention-wait

Audio/Video

Video 1: In our own words: Courtesy Mind Home | Mind, the mental health charity - help for mental health problems

Video 2: Dealing with an eating disorder: courtesy: NorthWest Boroughs Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

Video 3: Understanding and breaking the self-harm cycle courtesy: Dr Pooky Knightsmith www.pookyknightsmith.com

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – The Open University.