Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 5:53 PM

Session 1: Setting the scene by looking at the past

Introduction

In the first session of this course, you will look at the history of children’s mental health. Until the middle of the twentieth century, following the Second World War and the formation of government welfare services, children’s mental health was not recognised as the significant issue it is today. However, some children will have experienced mental health problems, even if these were left undiagnosed, and you will be examining some of the reasons why this might have happened.

You will look at a news account about children’s mental health and consider why there are currently reported increases in the numbers of cases of children with compromised mental health, and you will be encouraged to identify some of the reasons why this might or might not be the case. You will also be introduced to some of the ‘language’ associated with children and their mental health. This will hopefully make the content in later sessions more familiar to you. And finally, you will be encouraged to think about the resources within the child, the family, their community and wider society that can help children to develop ensuring good overall mental health.

It is important to highlight that contemporary Western views about children and mental health are not going to be held globally; some cultures as well as religions hold beliefs that mean they do not recognise mental health issues as an illness. Instead, the causes of behaviours in children that are outside the norm are sometimes attributed to other explanatory models, a contentious example being that a child is possessed by evil spirits.

Now listen to the following audio in which Liz Middleton, one of the course authors, introduces the session.

Transcript: Audio 1

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- describe an overview of the history of children and mental health

- outline the reasons why there is an increase in awareness of children’s mental health

- identify selected factors that can impact children’s mental health and wellbeing.

1 Historical perspectives of children’s mental health

The recognition that children may be vulnerable to developing diagnosable mental health conditions has started to emerge over the last hundred years or so. This is partly because, until modern times, children were regarded as little more than ‘adults in waiting’ and childhood was not regarded as a distinct life stage as it is today. There was a different understanding about how children develop and a lack of awareness that children think differently to adults. Another reason why it was thought that children could not be regarded as being mentally unwell is because behavioural problems were viewed as being caused by children being ‘bad’ rather than ‘mad’ (Rey et al., 2015). Children who did not conform to the expected norms of behaviour were often marginalised from society, punished harshly and labelled in pejorative ways.

The next section includes a timeline of some of the key events relating to societal views and developments in relation to children’s mental health. The sources used for this timeline include historical accounts from the field of child psychiatry as well as recently written reflections on the history of children’s mental health.

1.1 Key events in the history of children’s mental health

Below is a timeline of key events, predominantly drawn from the United Kingdom, that have influenced the ways that children’s mental health is viewed in countries such as the UK.

1800s: lunatic asylums emerged and children regarded as psychiatrically unwell, including those with learning disabilities, were institutionalised and removed from mainstream society.

1895: Henry Maudsley, a pioneer of psychiatry, wrote a psychiatry textbook posing the question ‘how soon can a child go mad? … obviously not before it has some mind to go wrong, and then only in proportion to the quantity and quality of mind which it has’.

The late 1800s: there was a lack of clarity about the causes of mental health conditions in children. However, during this time, a growing understanding developed that children could be affected mentally by the ‘psychological damage’ caused by grief, such as melancholia, or, to use a more contemporary phrase, depression.

1889: adolescence started to become recognised as a distinct stage of life, and puberty was recognised as a significant ‘cause of insanity’. Maxime Durand-Fardel (1889), another doctor who was a pioneer in psychiatry, highlighted the existence of suicide in children.

1919–1930: educationists such as sisters Rachel and Margaret McMillan (1919) and Susan Isaacs (1929), who were pioneers in nursery education, published books to explain their views about the importance of early childhood education. Their work made significant contributions to understanding how children develop emotionally and socially. Their work and practice remains an influence in contemporary nursery education.

1936: Jean Piaget, a psychologist, developed his theory of children’s cognitive development, which clearly demonstrated that children think in different ways to adults.

The Second World War (1939–45) had a profound impact on many children’s mental health. The experiences of many children in the UK included being evacuated to places of physical safety away from their families to live with people who were unknown to them. In many cases, children’s experiences had a negative effect on their emotional development and on their mental health.

In order to see the connection between challenging life events and how this impacts on children’s mental health, in the next section you’ll read about the real-life account of a woman remembering her experiences as a child during the Second World War.

1.2 Case study: the impact of war on children

Read the following case study about Sheila, a 6-year-old girl living in Birmingham in 1943 during the Second World War. Sheila’s experience is based on the account of a woman in her 80s, but she vividly recalls the experience of this period of her life.

Case study: Sheila

Sheila is 6, she is an only child and she lives with her mum. Until recently, they lived in a small house known as a back-to-back in the middle of Birmingham. It’s 1942, the fourth year of the Second World War, and there have been many nights of bombing across the country. Normally, the area where Sheila lives is not affected because the bombs are usually targeted on the factories which are further east; however, the planes went off course and dropped a barrage of bombs, one of which hit Sheila’s home and destroyed it.

For the last month, Sheila and her mum have been living with her aunt and her four cousins. Sheila has to sleep on the sofa because the house is so crowded. Each night, for the last week, the siren has gone off at 1 am to warn people that the planes are nearby. The siren means that they all must go to the nearest bomb shelter to wait for the planes to finish their mission.

Everyone is exhausted, food is in short supply and people are hungry. Sheila hates the noise caused by the explosions that happen after the bombs hit a target. However, it’s almost worse waiting for the noise to happen. Sheila feels jumpy and anxious, and she knows she would feel better if she had Snowy, her much loved toy sheep. He had been with her all of her life and he was a dull grey with threadbare patches, and he smelt and felt like home. However, Snowy disappeared when their home was destroyed, and Sheila feels lost and alone without him. She feels that life will never be the same again.

Just as Sheila thinks that things can’t get any worse, two things happen. Firstly, her dad – who is away in France fighting in the war – is reported as missing in action. This means that he may have been taken a prisoner, or he may have been killed, but they don’t know which. The second thing that happens is that Sheila’s mum finds a job in a factory. As money is tight, she decides to take the job, but this means that nobody is available to look after Sheila. So Sheila is evacuated to the countryside, away from the bombing, to live with people who can look after her until it is safe to go back home.

The people who take in the evacuees are strangers; they often live on farms and some use the children as unpaid workers. Life is physically very hard because the children are required to get up early and do chores such as going out in the dark mornings in all weathers to collect eggs or milk cows.

Sheila joins the local school and, at first, she is a source of curiosity to the other children who can’t understand her different accent but try to include her in playtime. However, Sheila is so miserable that she finds it difficult to respond to their attempts to include her, so the other children eventually stop trying to make friends. Sheila becomes withdrawn, finding it hard to speak, eat and sleep. She misses everything about home and feels completely alone in the world.

Sheila returns to her mother after the end of the war. Her life settles down into a routine with her mum, and she happily fits in to her old school again. It turns out that her father has been a prisoner of war, so he too returns home at the end of the war. He is deeply affected by his experiences but takes solace in his family and they go on to have a much-loved brother for Sheila.

Sheila’s adverse childhood experience does not appear to affect her mental health in the long term; however, her experience as a child living through the terror of bombs falling from the sky during the night leaves her with a fear of loud noises, which never goes away. The feeling of loss and separation experienced as an evacuee leaves her with a strong desire to always be with people and have company; her engaging nature means that she has many friends who help to meet that need.

Activity 1 Exploring the mental health impact of being an evacuee in the Second World War

Answer the following questions about the case study.

- What are the reasons why Sheila’s mental health could be affected by her living conditions and external events?

- What events and circumstances appear to help her to recover from her experiences?

Throughout this course, you’ll have the opportunity to record your answers to activities in interactive boxes and save them. No one else will be able to view them. If you’d like to, add your answers to the questions in the box below.

Discussion

The impact of Sheila’s experience could have been very different: she could have experienced long term trauma, which could in turn have resulted in life-long difficulties with her mental health such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress. It is not always obvious why some children are more vulnerable to the effects of adverse experiences than others, although there are several protective factors, which will be discussed further in this course. In Sheila’s case, the absence of mistreatment during her time as an evacuee, the return to a happy routine at home and many positive relationships will undoubtedly have helped her to heal and recover from the experience.

1.3 The Second World War in Europe

In Europe, the Second World War meant that many children were displaced from their home country and consequently suffered physical and emotional trauma. These accounts about children and war from Western Europe are historical, but it is important to remember that children in the present day are experiencing similar challenges in conflict zones around the world. In the next activity, you’ll look at another child’s experience of the war.

Activity 2 Irja’s story

This video recounts the experience of Irja, who as a child had to leave her home in Finland during the war. As you watch this short video, consider the factors that may have helped her to survive this experience.

Transcript: Video 1

Discussion

Irja highlights the harshness of living as a displaced person; however, what is evident in her story is the importance of remaining part of a family. The video also illustrates the importance of having a person’s physical needs met; for example, having enough to eat. The video also makes a link between the importance of having the basic physical need of clothing supplied as a factor that can contribute to positive mental health and wellbeing. The gift of the brown shoes meant that Irja was able to attend school, where she would have had the opportunity to develop emotionally, socially and intellectually.

1.4 Post-Second World War period: key events in children’s mental health

Below is another timeline, focusing on post-Second World War events.

1949–1969: John Bowlby, who was a psychiatrist, started his pioneering work about children’s emotional development shortly after the Second World War by studying the effect on children of separation from their mothers. From this work he developed his theory of attachment, which was first published in 1969.

1949: The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) was set up to improve the lives of children who had been affected by the Second World War.

1953: UNICEF became part of the United Nations and their name was changed to the United Nations Children’s Fund. The work of UNICEF continues today, helping to improve the mental and physical health of children who are caught up in war and conflict around the world.

1959: The United Nations introduced the Rights of the Child, which meant that children became regarded as citizens with rights in many places in the world. Other significant events included the development of evidence-based therapies and forms of medication which were effective and safe to use in the treatment of children with mental health conditions.

1989: The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child was a global event that turned a spotlight on children and their welfare. Around this time, a number of cases emerged that highlighted the exploitation of children and this led to the creation of policies designed to protect children and improve their mental health. In England, the Children Act (1989) is an example of legislation that was passed to improve children’s lives and wellbeing.

1995: Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) began to be set up across England and Wales, and elsewhere, to bring together multi-disciplinary teams of professionals to diagnose, treat and support children and young people with mental health conditions.

Activity 3 Reflecting on history

How can looking at children’s mental health through an historical lens help our understanding of the contemporary situation?

This brief overview of the history of children’s mental health highlights that children have always experienced mental health problems. However, it is only in relatively recent times, that is, since about 1940, that this has become recognised as such and that specialist services and treatments have been developed. This section summarises some of the key events that have influenced the shift in the belief that children are not capable of experiencing mental health problems to the contemporary situation in many countries, where it is recognised that children can experience profound mental health conditions.

2 Contemporary children’s mental health

The previous section explored a brief snapshot of the history of children’s mental health and highlighted that children experiencing mental health problems is not a new phenomenon. Children have always had mental health problems, but because of their status in society, their needs have not always been recognised and addressed. Nowadays, in part due to advances in our ability to diagnose mental health conditions in children, it has been estimated that as many as 10%–20% of children have a diagnosable mental health condition (World Health Organization, 2019). For many, their issues will be in the ‘mild-to-moderate’ range, while others will have severe and possibly enduring mental health conditions. This situation is of concern to individuals and their families and also has long-term consequences for society. However, at this point, it is important to have a look at some of the evidence relating to the relatively high prevalence of mental health conditions in children.

Activity 4 Exploring some of the facts around children and their mental health

Professor Tamsin Ford, a child psychiatrist, led a study about children and young people’s mental health, and the findings were reported in a BBC news article. In a nutshell, the study was based on assessments completed with 10,000 child and adolescent participants. Follow this link to access the article (make sure to open the link in a new window/tab so you can return here easily):

Is young people’s mental health getting worse?

As you read the article, consider that the report states that in 1999, the incidence of children with a mental health condition was estimated to be 11.4% of children below the age of 16. In 2017, the proportion was estimated to have increased to 13.7%. So, on the surface, over an 18-year period, there was a 2.3% increase in the number of children who were reported as having a mental health problem. However, clearly establishing how much of the reported rise represented an actual increase in children and young people experiencing problems, and how much is down to better awareness of symptoms and/or diagnosis, is challenging.

Consider the reasons given in the report for the possible increase in terms of proportionately more children having mental health conditions.

Discussion

As you read the report, you may have been struck by the fact that Ford was surprised that there had not been a bigger increase in the number of children being diagnosed with a mental health condition. You may have also noticed in the timeline that CAMHS was set up in 1995. This was a key event in addressing children’s mental health because numerous specialist services were created to support children with mental health conditions.

Although this report states there has ‘only’ been a 2.3% increase in the number of children being diagnosed with a mental health condition between 1999 and 2017, this still means that there is a sizeable proportion of children living with a mental health condition. Clearly, it is important to consider the reasons why there are such significant numbers of children with compromised mental health, both to further our understanding, but also to support children to develop positive mental health. You will explore these issues in the rest of this course.

3 Resources that promote a child’s mental health and wellbeing

There are many factors in children’s lives that can help to contribute to their wellbeing which in turn can help them to have good mental health.

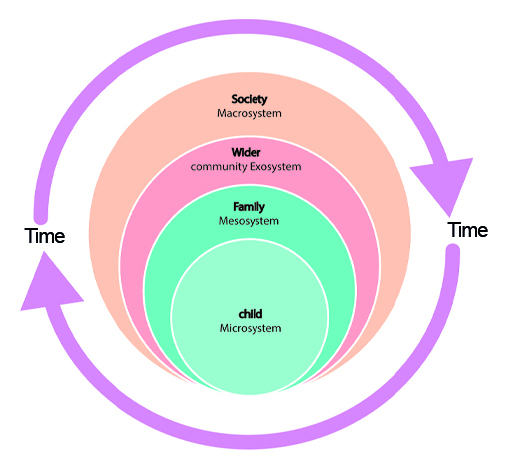

To illustrate this point, you will now look at the work of Urie Bronfenbrenner, an American sociologist who researched the interaction between the individual and their environment. Bronfenbrenner developed a theory of how each child’s development is influenced by their relationship with the groups and communities around them as well as with wider society. His theory was named the bioecological model (1979) and he illustrated the theory in a diagram which put the child in the centre of a nest of circles. Moving out from the child, each circle represented a system around the child. This theory is useful to illustrate the influences on children’s mental health.

In Figure 8, the systems around the child have been separated out to illustrate how we can think about the factors within each system.

The inner circle represents the resources within the individual child (the microsystem), then moving outwards, the resources within their family (mesosystem) and local community (exosystem) such as pre-school/school or places of worship, and, finally, the outer circle (macrosystem) which represents the resources within wider society that help children to develop good mental health. Around each of the systems is the passage of time, suggesting that situations and circumstances evolve over time and will change as a matter of course in response to external events. The child themselves will also continue to grow and move across the systems as they move further into the world and away from their family networks.

Earlier in this session you saw how, at different points in history, wider social issues such as war have had a significant impact on how families function and the extent to which children thrive in more challenging environments.

You will find it helpful to return to these different systems as you examine how various practices and policies might affect children’s wellbeing, and the ways that the different ‘layered systems’ might work together to promote more positive mental health in young children and their families, as well as the communities in which they live.

Activity 5 Identifying resources that can make a positive contribution to children’s mental health

Make a list of the resources within each of the circles that you think can make a positive contribution to children’s mental health.

Discussion

The following are some suggestions of the resources that you may have listed for each of the systems. Don’t worry if you included other resources or worded things in a different way. The main point is that each of the different systems has an influence on the others.

- Within the child (the microsystem): determination, intelligence, resilience, perseverance, a sense of good wellbeing.

- Within the family (the mesosystem): an emotionally responsive home with settled routines, good relationships, and all physical needs met. In Session 3, you will look at the important process of attachment. You will understand how the building of secure attachments in the early years can help to develop positive views of self and effective future relationships with others.

- Within the community (the exosystem): good quality pre-schools and schools, health services, a safe environment with access to outdoor areas for play. You will have the opportunity to reflect on the ingredients that make up good quality care and education in Session 5. In the same session, you will focus on the significance of play for the promotion of children’s mental health and wellbeing as part of the early years curriculum.

- Within society (the macrosystem): laws that protect children and help prevent harm that can make the occurrence of adverse childhood experiences more likely. Positive societal attitudes that take account of children’s rights will be a resource that you will explore more fully in Session 4.

Safeguarding laws in England are an example of the national approach that states that it is everybody’s responsibility to protect the welfare of children, and therefore these are resources within society. You will be introduced to these laws in Session 5.

It is worth bearing in mind that even if children have many of the resources available to them, some children will still develop a mental health condition. And the opposite is also the case: children who have experienced a great deal of adversity and are missing many of the positive factors in the systems around them do not necessarily develop poor mental health.

4 Mental health terms

Bio-medical terms can be like a different language and, as with any language, learning it can help us to understand what is happening. This section gives definitions and explanations about some of the language associated with children’s mental health. There are many definitions for some of these terms.

Mental health: We all have mental health and, in a similar way to physical health, it can fluctuate in response to a range of factors. The World Health Organization defines mental health as:

… a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.

If we are not able to cope with the stresses of life and can’t do the things that make us feel we are achieving something positive, we can start to lack confidence and motivation. This is the same for children as it is for adults. Imagine being a child who is overwhelmed by events that are beyond their control, but must still attend school and be tested, or participate in activities that they have no motivation for.

Mental illness or a mental health condition: A disorder of the mind, which seriously affects a child’s functioning as well as their behaviour or thinking over an extended period of time. There are a number of mental health conditions, the most common in children being depression, anxiety and trauma-related problems as well as issues to do with poor conduct. There will be more about these conditions later in the course.

Wellbeing: A concept that has many definitions, but is usually associated with being ‘comfortable’, happy, well-adjusted and healthy. Other definitions make reference to the quality of an individual’s life. In relation to children, their level of wellbeing can often be judged in relation to their behaviour. A child who is experiencing a poor sense of wellbeing is more likely to be unhappy, have difficulty in concentrating and be unable to engage adequately with everyday activities.

Diagnosis: The identification of the nature of an illness or other problem by examination of the symptoms. Medical doctors are the professionals that usually diagnose mental health conditions, including among children. A diagnosis is helpful to enable a person to access appropriate and evidence-informed treatments, as well as for advocacy purposes (e.g. where parents who have a child with the same mental health condition can support each other). However, a diagnosis is not always welcome, as unfortunately mental health conditions, even in children, can be stigmatised.

Developmental norms: A sound knowledge about developmental norms is essential in terms of ‘making sense’ of children and mental health conditions. For example, a young child that has an imaginary friend that they speak to in primary school is perfectly normal (and is thought to be associated with being intelligent), whereas talking to an imaginary friend for older teens is seen as unusual and often problematic. Hence, children with a mental health condition will present in ways that are outside of the norm, but determining what is within the ‘normal range’ is vital in terms of establishing if a problem is really a problem.

Risk factors: A risk factor in terms of child mental health is any attribute, characteristic or exposure of an individual that increases the likelihood of developing a condition. In relation to younger children, salient risk factors that can impact on their mental health include a clear lack of routine, not having their physical and emotional needs met, or living in a family where there is domestic violence.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE): Stressful events that can occur in childhood including, but not limited to, the following:

- domestic violence

- parental abandonment (e.g. through an acrimonious separation or divorce)

- having a parent with a mental health condition where this is poorly supported

- abuse (physical, sexual and/or emotional)

- neglect (physical and/or emotional)

- growing up in a household in which there are adults experiencing alcohol and drug use problems.

Protective factors: Conditions or attributes in individuals, families, communities or wider society that mitigate or eliminate risk in families and communities, thereby increasing the health and wellbeing of children and families. For example, communities that have plenty of green open spaces and well-equipped schools are associated with enhanced health and wellbeing for children.

Nature and nurture: In the ‘nature versus nurture’ debate, ‘nurture’ refers to personal experiences ‘growing up’ and the impact of a person’s context or environment. Nurture is therefore directly related to a person’s childhood or upbringing. However, nature is to do with a person’s biology, including their genes. A person’s physical ‘make up’ (e.g. their potential to grow to a certain height) and aspects to do with their personality traits are determined by their genes. The person has little control over certain aspects or features of themselves, irrespective of where they were born or how they were raised. It is now generally accepted that children grow and develop as a result of a complex interplay between both nature and nurture.

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS): CAMHS are a form of specialist mental health services, primarily delivered by the National Health Service in the UK. CAMHS provide a range of services for children and young people who have difficulties with their emotional or behavioural wellbeing. CAMHS vary depending on the catchment area they serve – with many having waiting lists, and struggling to meet the demands for their services.

5 Personal reflection

At the end of each session, you should take some time to reflect on the learning you have just completed and how it has helped you to understand more about children’s mental health. The following questions may help your reflection process each time.

Activity 6 Session 1 reflection

- What did you find helpful about this session’s learning and why?

- What did you find less helpful and why?

- What are the three main learning points from the session?

- What further reading or research might you like to do before the next session?

6 This session’s quiz

Well done – you have reached the end of Session 1. You can now check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window and come back here when you have finished.

7 Summary of Session 1

Now that you have completed this first session, you will hopefully have gained an overview of the history of children and mental health. You have also explored some of the reasons why there is an increase in awareness of children’s mental health. Some of the language associated with mental health has been defined and you have started to identify factors that can impact children’s mental health and wellbeing.

You should now be able to:

- describe an overview of the history of children and mental health

- outline reasons why there is an increase in awareness of children’s mental health

- identify selected factors that can impact children’s mental health and wellbeing.

In the next session, you will delve further into some of the causes of mental health conditions in children. You will also examine the possible impact of compromised mental health on children’s development and education and explore some of the likely ‘triggers’ of anxiety in children.

You can now go to Session 2.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Jackie Musgrave and Liz Middleton. It was first published in October 2020.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

Figure 1: Anna_Zaitceva; Shutterstock.com

Figure 2: Out of Copyright; taken from: http://juliangrenier.blogspot.com/ 2017/ 10/ susan-isaacs-remarkable-woman-educator_26.html

Figure 3: Imperial War Museum; LN 6194

Figure 4: ullstein bild; Getty Images

Figure 5: UNICEF/UNI41896/Unknown

Figure 6: Convention on the Rights of the Child; UNICEF

Figure 7: Africa Studio, Shutterstock.com

Figure 9: Elena Efimova; Shutterstock.com

Audio-visual

Video 1: UNICEF

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.