Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 5:43 PM

Session 2: Increasing your knowledge of mental health

Introduction

It may be an obvious statement to make, but increasing your knowledge of the language relating to mental health can increase your understanding and, in turn, this can help to increase your confidence in supporting children’s mental health. In this session, you will look at definitions of some of the mental health conditions that commonly affect young children. These include anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, phobias and behaviour disorders. Other pertinent issues, in particular school refusal and sleep problems, will also be explored. You will look at the impact of mental health issues on children’s education and development, and identify some possible ‘triggers’ for children’s anxiety in early childhood and school settings.

Now listen to the following audio in which Jackie Musgrave, one of the course authors, introduces the session.

Transcript: Audio 1

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- appreciate that children’s mental health can vary for individuals and over time

- describe some of the common mental health conditions that affect children

- understand some of the factors that are associated with mental ill-health in children

- explore some of the effects of poor mental health and illness on children’s education and development

- identify ‘triggers’ for anxiety in children.

1 Understanding children’s mental health

In a similar way to our physical health, our mental health can go through sub-optimal periods and will not be as good as we would like. We can go through periods of time when we seem to get ‘every cold going’, stomach bugs or simply feel ‘off colour’. In a similar way, our mental health can be good, not so good or downright bad.

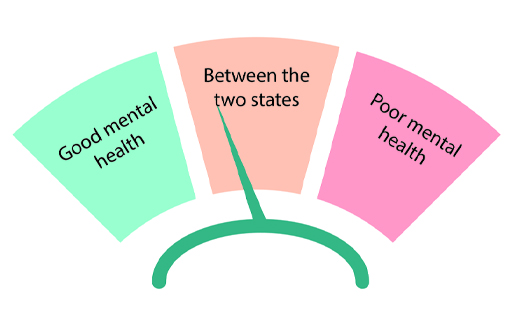

It may be helpful to think of mental health as being like a windscreen wiper: on one side mental health can be good, but it can move across to the opposite side where it is bad. There is a great deal that we can do to keep our mental health on the good side of the spectrum.

Figure 2 represents mental health as a spectrum, with good mental health on one end and poor on the other. In a similar way to a windscreen wiper, mental health is not static and it can move from one end of the spectrum to the other.

In a similar way, there can be variability in children’s mental health, meaning that it can vary between being ‘good’ (or ideal) or ‘bad’ (or compromised). However, there are significant differences between adults and children. For instance, very young children are likely to have less understanding about their feelings: they can find it difficult to clearly identify their emotions and they will not have the same vocabulary to describe their emotional state using words. For example, a young child’s anxiety may manifest in physical form, whereby they have a ‘funny feeling in their tummy’ about a situation they are in (or anticipate they will soon be in). An adult is more likely to recognise the physical sensation they are experiencing (e.g. ‘butterflies in your stomach’) as a feature of an anxious state.

However, for a young child in an anxiety-inducing situation, it may be a challenge to understand the feelings they are experiencing, and to regulate their emotions so that they do not become overly distressed. For instance, for a very young child, the thought of being separated from a loved adult can cause ‘a funny tummy feeling’. Also, it is likely that very young children will not have the vocabulary and language development to be able to articulate their thoughts and feelings. Very young children, in particular around the age of two, are likely to demonstrate their emotions, including anxiety, by displays of high emotion including crying, shouting and kicking; in other words, by having a tantrum straight after being separated from a loved one (also known as an attachment figure). These responses are not usually seen as majorly concerning for very young children, but the same sort of response in older children is usually a sign that could mean issues in terms of their mental health. If a child is frequently experiencing situations that cause anxiety which seems disproportionate to the event (e.g. a Year 5 student having a ‘tantrum’ every time they are dropped off at school), this is usually a sign that a ‘problem is a problem’ which is impacting on their general wellbeing. This older child is more likely to have compromised mental health and be at risk of developing a mental health condition which will require a professional assessment. Therefore, understanding children’s behaviour for their age and stage of development is extremely important for all adults involved in the care and education of young children.

2 Understanding children’s development

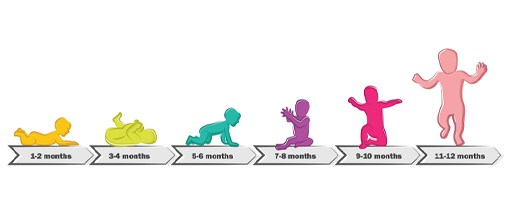

Think of a newborn baby. Imagine how small they are and how they rely on the adults around them for their physical and emotional needs to be met. Now fast forward to a baby’s first birthday. Most will have tripled their birth weight, might be walking, able to communicate a range of their needs and will have developed their own personality. This first year of life is, for most children, a time of rapid growth and development.

The term ‘child development’ is used to describe the expected changes that occur from birth and throughout childhood; the areas of development are described as physical, intellectual, language, emotional and social. The areas of development have been traditionally separated out in order to make the study of children and their development easier; however, realistically, the different areas overlap with each other. And the way that a child develops in each area can impact on their sense of wellbeing and, in turn, can influence whether their mental health is seen as ‘good’ or ‘bad’.

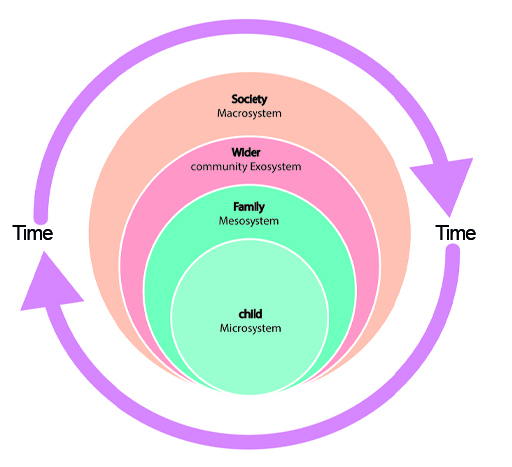

Although the study of children and their development has identified a range of skills, growth, maturation or learning that a child is expected to have achieved by a certain age, it is not necessarily the case that each child will develop in the ways that psychological theories have outlined. There are many influences on children’s development and, returning to the diagram you first saw in Session 1, the level of development will depend on the systems and resources around the child.

If a child is lacking the factors that make a positive contribution to their development, this can mean that a child may not meet the expected norms of development. On the other hand, if children have access to many of the positive influences on development, some children will exceed the expected norms. However, despite the systems around them and the resources available to them, some children can still experience compromised mental health.

Gaining an understanding of how children develop is important because it helps adults to understand the expected behaviours and abilities for a child at a certain age. For example, an eight-month-old baby is likely to feel very anxious about the prospect of being separated from their main carer or attachment figure and they are likely to show their distress by becoming clingy and crying. As children grow and develop, they will learn that their main carer will return, so even if they are not completely happy about being separated they can be reassured more quickly and easily when separated.

There is a great deal that adults can and should do to prepare children for transitions between home and care and education settings; you will focus on this in Session 5. If, despite careful preparation and attention to the child’s needs, a child exhibits behaviour that is not typical for their stage of development, this may be an indication that something is amiss.

Understanding the expected norms of development can be helpful, but it is also important to understand that each child is unique and will develop in their own way and in their own time. However, knowing the child’s ‘unique ways’, their general behaviour, development and preferences is helpful so that any concerning changes that last for an extended period can be identified and addressed.

3 Knowledge of mental health

As you’ve already seen, children’s mental health can fluctuate. While there is much that can be done to support and improve children's wellbeing and mental health, some children will develop a diagnosable mental illness. In the following sections, you will look at some of the common mental health conditions that can affect young children.

3.1 Definitions of specific, common mental health conditions or issues affecting young children

This section gives some definitions of mental health conditions that most commonly affect young children:

Anxiety: A feeling that can cause overwhelming emotions, nervousness and sometimes fear.

Anxiety may develop because a child is predisposed to being anxious, or it can develop as a consequence of adverse experiences. Anxiety can cause physical symptoms, such as ‘butterflies’ in the tummy, or what children may describe as ‘funny feelings in my tummy’. Children may become breathless and panicky, which can result in a panic attack. Very young children can experience anxiety related to a range of triggers such as a food phobia, being in an enclosed space or issues to do with going to the toilet. Some children can develop ongoing anxiety that becomes so overwhelming that they find it difficult to lead their lives. Treatment for very young children is unlikely to be medication and more likely to be psychotherapeutic approaches such as talk-based treatments, like cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A neurological disorder that causes poor concentration, hyperactivity and impulsive behaviour (Burton, Pavord and Williams, 2014). It is worth mentioning that these signs can be present in a child, but may not meet the threshold to be diagnosed with ADHD. However, frequent persistence of the aforementioned features which has a considerable impact on the child’s functioning, and where the issues are present across a range of environments (in particular school and home) is suggestive of ADHD. Treatment of this condition includes medication and psycho-social interventions. It is also extremely important that there is support for parents and professionals, in particular the child’s teacher, to understand and adequately assist children with ADHD. It is also important to avoid being overly negative or punitive in response to behaviour that is extremely difficult for the child to manage (e.g. fidgeting) and instead to develop positive approaches that channel the energy and enthusiasm that many children with ADHD exhibit.

Autism spectrum disorders: Autism is a complex condition that is more common in boys. The symptoms can be relatively mild but, as the name suggests, because the symptoms go across a spectrum, they can also affect children in ways that are more noticeable and severe. Autism can impact all areas of children’s development in small or profound ways. In particular, children with autism can struggle in areas relating to social and communication development and may find it difficult to understand certain social situations. Children with this condition can become especially focused, often to the point of obsession, with certain play activities. They can also become fixated about particular foods, smells and sensations associated with certain objects.

For more information about autism, look at the course Understanding autism which can be found on the Universal level courses section of the North Lanarkshire Council Skills Pathway portal.

Behaviour disorders: These refer to children’s behaviour that is related to extremes of the norms, meaning that children can be especially disruptive, destructive and/or aggressive to the point of being persistently anti-social. Two of the most commonly occurring conditions are conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Behaviour disorders can be accompanied (also known as being ‘comorbid’) by other conditions such as anxiety and ADHD. As with autism, behaviour disorders are more common in boys.

Depression: Depression and depressive disorders can affect a wide range of people, including children. It is characterised by protracted low mood and impaired functioning, which can lead to a reduction in activity, reduced motivation and challenges in experiencing everyday pleasures. Diagnosing depression in children can be challenging because many of the symptoms or features that affect adults with depression, such as repeated crying, sleep disturbance and lack of appetite, are common problems in childhood. If such symptoms carry on, along with impact on functioning and persistent sadness over a period of time, this may indicate that a child is depressed. Rates of depression are fairly low for children before puberty.

Enuresis and encopresis: Enuresis is bladder incontinence and encopresis is faecal soiling that persists beyond the age when it would normally be expected that a child would have gained control over their bladder and bowel function. It is important that physical causes are eliminated before considering that there are psychological reasons for incontinence (and it is important to remember that night-time bedwetting is not unusual in children even when they are at primary school). Bedwetting at night, or nocturnal enuresis, can be managed by behavioural therapy; for instance, by using an alarm pad that is activated when the child starts to pass urine. Encopresis can sometimes be linked to a child’s anxiety about passing faeces as a consequence of embarrassment or limited toilet training.

Phobias: These can be described as an extreme fear of something that causes great distress and anxiety. Phobias can be specific, such as agoraphobia, ‘a fear of open spaces’. Phobia-inducing objects can range from obvious sources such as snakes and spiders to balloons, germs and even clowns. Cognitive behavioural therapy is a frequently employed and effective form of treatment for phobias.

School refusal: Children can develop extreme anxiety about going to school and there can be a wide range of reasons why they are refusing to attend. In some cases, children can become phobic about attending school; this is usually a symptom of an underlying cause. Examples of such causes include bullying, anxiety about separation and being away from home or inability to cope with academic expectations. Careful exploration of the underlying reasons and close collaboration with school staff is needed to identify the issues.

Sleep disorders: Sleep is essential for all people; however, it is especially important that young children have adequate amounts of sleep. This is important for physical growth and development as well as for good mental health. Some young children will be easy to settle and are ‘good sleepers’ (and eaters too), while others will take longer to fall asleep and will wake more often. Young children require long periods of sleep and naps (for young children) during the day; the amount of sleep needed can be under-estimated by adults and children can become sleep-deprived. It is especially important that young children have a routine that allows time for them to wind down and relax in preparation for sleep.

Of course, establishing good sleep routines can be easier said than done, and there are many reasons why young children can develop issues to do with sleep. Identifying how and why a child has developed a pattern of interrupted sleep can be a little like working out whether the chicken or the egg came first, because if a child is developing anxiety about something, this can prevent them from sleeping. Lack of sleep will exacerbate how children feel and impact on their wellbeing and in turn, can be a cause of poor mental health. Plus, some children will just find it easier to sleep, as is the case with adults too. As you will explore further in Session 8, time spent on over-stimulating electronic devices and social media later at night can also have a negative impact on children’s sleep patterns.

4 The impact of physical health on mental health

In the previous section, you explored some of the common conditions that can affect young children’s mental health. However, children’s mental health can also be impacted by their physical health. For example, children are increasingly being diagnosed with chronic (meaning that they are ongoing) health conditions (World Health Organisation, 2020). The most common chronic conditions that affect young children in high income countries include asthma, diabetes and eczema. As many as 10–15% of children have asthma (NHS England, n.d.), which means that between 3 and 5 children in a class of 30 are likely to have asthma. Eczema is thought to affect 11% of young children and the number of children with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes is also increasing.

Chronic conditions can have a profound impact on children’s lives; for instance, they may have dietary restrictions, or they may need to use inhalers or other medications, such as injections, to manage the symptoms. The symptoms of chronic conditions can set a child ‘apart’ from their peers, be painful and unpleasant, and, in some cases, life-threatening. For example, asthma attacks are still a cause of child deaths in the UK. It is not surprising that the presence of a chronic condition can be a source of great anxiety to a child (and their family) with one or more chronic conditions. It is not unusual for children to have a combination of chronic conditions; asthma, eczema and allergies are all conditions that frequently affect children. Physical conditions can have profound psychological consequences and sometimes there can be a range of interrelated symptoms that can create a complex picture in terms of a child’s overall health and wellbeing.

Activity 1 The possible impact of chronic health conditions

Read the following case study about Charlotte: her experience is based on a child taught by the author of this course. As you read it, consider the following questions:

- What are the possible effects of Charlotte’s chronic physical health conditions on her mental health and wellbeing?

- How could adults support Charlotte to improve her physical health and wellbeing?

Case study: Charlotte

Charlotte is 6 and she has had eczema since she was 5 months old. The eczema has been widespread and she has large patches of ‘angry-looking’ skin, which is red, inflamed and weeps fluid. The itchiness causes her to scratch relentlessly, to the extent that she causes herself to bleed. Despite her mother’s diligent application of creams and avoidance of many of the known triggers that provoke Charlotte’s eczema, it continues to be troublesome and it is having a profound impact on many aspects of her life as well as her family’s life. For instance, night times have always been difficult: Charlotte’s sleep has been affected by eczema because she has an almost continuous need to scratch.

As well as having eczema, Charlotte has recently been diagnosed with asthma. Before the diagnosis, she was coughing at night, which meant she was waking frequently; this also impacted on her sleep pattern. Asthma symptoms also affect Charlotte during the day; because she is short of breath, she finds it uncomfortable to run around outside and play with her friends, so she finds it easier to walk around with the teacher during playtime instead.

Furthermore, Charlotte is going through a period where her eczema is particularly troublesome. Her hands are especially affected with dry crusts that are prone to bleeding. Some of the children have noticed the blood and are starting to make comments that are very hurtful to Charlotte. Because of the children’s comments, Charlotte has started to be excluded from playtime activities. She has also realised that she is not being invited to birthday parties.

In addition to the social exclusion, Charlotte’s lack of sleep means she is always tired during the day. This means she is irritable with her friends, as well as finding it difficult to concentrate, so she is also struggling to keep up with her schoolwork. Her asthma is especially bad during the early summer when hayfever is at its worst; taking part in Physical Education (PE) and school events such as sports day is difficult for Charlotte. Consequently, she is not able to have many opportunities to exercise and to benefit from taking part in physical activity, which is important for a child’s wellbeing.

Discussion

Charlotte’s story is not unusual: asthma and eczema are conditions that often go together (i.e. are comorbid). The symptoms, such as the itchiness that eczema causes, can be very troublesome. Also, because her skin is so affected, the condition is very visible. Such visibility can cause distress to the child and, sadly, it can be a cause of social exclusion, as in Charlotte’s case.

In the same way that adults have a responsibility to teach children about tolerance and understanding in relation to race, colour, disability and class, there is also a responsibility to do the same in relation to other children's chronic health conditions.

In Charlotte’s case, it may be helpful for her teacher to work with her mother and the school nurse (if one is available) to identify ways of improving her participation in school life. The school nurse is likely to be able to offer support to Charlotte and her mum in improving Charlotte’s physical health; for example, by ensuring that she has access to creams and other medication while she is at school, which in turn would improve her wellbeing and mental health.

5 The impact of mental health issues on children’s education and development

In the following sections, you will explore the potential impact of mental health issues on children’s development and how, in turn, mental health can affect their education.

You’ll start by focusing on how mental health conditions can affect children’s development.

5.1 The potential impact on children’s development

The presence of a mental health condition can impact on children’s development in a range of different ways. Anxiety can impact on children’s social development because they can find it difficult to feel confident in interacting with other people. It can also impact on their speech and language development to the extent that they can become selectively mute, meaning that they will choose not to speak in certain places (or to certain people), usually when at school, but will do so when at home or on their own with one other trusted person. Anxiety and ADHD (in particular when inattention is a major feature) can reduce a child’s ability to concentrate, which is likely to impact on a child’s educational attainment.

5.2 The potential impact on children’s behaviour

Children who are experiencing mental health problems, especially those which are considered ‘externalising disorders’ (such as oppositional defiant disorder) will have accompanying behaviour or ‘conduct’ problems. Disruptive behaviour can be the child’s way of letting adults know that they are experiencing emotions that are overwhelming them. How adults respond to children’s behaviour can help to defuse a situation where a child is displaying what may be regarded as unacceptable behaviour. However, when it comes to young children, there is not a ‘one size fits all’ approach. How we respond to a child’s behaviour will depend on the child’s age and stage of development and the adult’s expectations around what is acceptable.

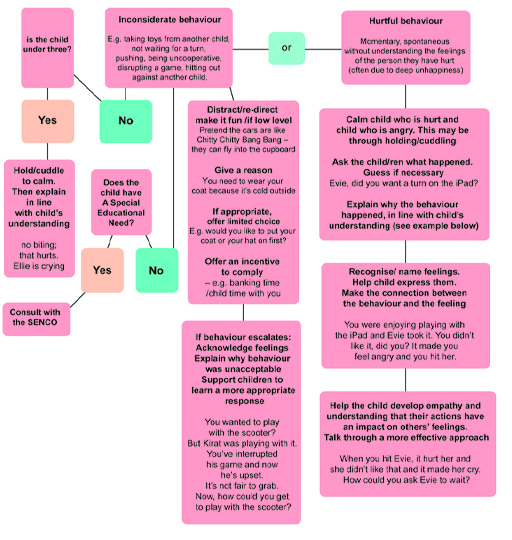

While there isn’t a single approach to managing young children’s challenging behaviour, there are some principles that should be taken into consideration when responding to a child’s misbehaviour. Look at the behaviour management toolkit in Figure 12, which is a flowchart that illustrates the considerations that need to be taken into account.

Activity 2 Managing the behaviour of children under 5

Look at the following scenarios and use the behaviour management toolkit in Figure 12 to consider your response to how adults – that is, parents, practitioners, teachers or health visitors – can work with the children in each of the examples. Note: SENCO stands for Special Educational Needs Coordinator. They are specialist school teachers who support children with additional needs.

- Mollie is 2. Having been an only child, she has recently had a new sister. Mollie has started biting other children at pre-school.

- Arun is almost 5. Despite his parents and the practitioners in his setting using a consistent approach to managing his behaviour, he is proving very difficult to handle. He constantly interrupts when other people are speaking and disrupts other children’s play, often violently.

- Evan is 3 and a half and his mum has recently died. He used to be a very happy boy, but he has become deeply unhappy and displays his grief-related emotions by being aggressive and angry towards others.

Discussion

In your response, you may have considered the possibility that Mollie’s behaviour has changed because she is feeling that she is getting less attention since her new sister has arrived. And she may have learned that biting someone is a very good way of getting attention. As outlined in the toolkit, holding and cuddling Mollie (rather than responding with anger), while explaining to her why she shouldn’t bite, is the right response. Additional responses and processes are likely to be needed, to ensure the child who was bitten is supported and that Mollie is stopped from biting other children in the future.

At almost 5, Arun is proving resistant to a calm and consistent approach to help support him to manage his behaviour. It may be that he has a mental health condition that is yet to be diagnosed, such as ADHD, that is affecting his behaviour. Although it is very important not to jump to conclusions, as a thorough professional assessment will be needed to confirm a diagnosis, it is important to observe Arun’s behaviour to see if there are any clear triggers or obvious antecedents that occur immediately before the problematic behaviour. It would also be useful to discuss Arun with the setting’s special educational needs coordinator (SENCO). The SENCO will have undertaken training to help support and guide practitioners to understand and manage children with problematic behaviour.

Evan is obviously responding to his bereavement and feelings of grief and loss, and it is often a human response to express such feelings by becoming angry. At 3 and a half, Evan’s feelings will be further compounded by his lack of understanding about death. Evan will need validation, an empathetic approach and other social support to help him cope. Working with his remaining family and main carers will be needed. Evan will benefit from age-appropriate play opportunities and books that tackle the subject of loss and bereavement. There are charities that can help children who have experienced bereavement, such as Young Minds and Cruse.

5.3 The potential impact on children’s education

Some very young children may have caused concern in relation to their social and emotional expression. As a result, they may have been assessed and their needs identified. However, for some children, prior to attending formal education, such needs may go unnoticed and it is not until they encounter group situations with multiple demands and expectations that problems start to become evident. Conversely, a number of children with significant mental health issues can go unrecognised for long periods after attending formal education because they are not a ‘management problem’ in the classroom or at home.

The more formal requirements of school may be a challenge to very young children who are at the early stages of developing peer-related social skills, which take time to develop. In addition, the expectations of school may be very different to those at home and an inconsistent approach can be confusing for children. With careful management, such issues can often be resolved.

However, some children with problematic behaviours may find it significantly more difficult over time to initiate, establish and maintain healthy relationships with adults and/or peers. They are also likely to find it difficult to regulate their emotions.

Here are some of the indications that a child is experiencing difficulties in school:

- withdrawn behaviour

- challenging, overactive and/or disruptive behaviour

- tantrums and ‘meltdowns’

- over-controlling behaviours

- panic attacks

- lack of attention and focus

- mind seeming to go blank

- irritability

- low mood

- low levels of energy

- extreme tiredness

- poor self-esteem

- lack of confidence

- little motivation

- increasing levels of anxiety

- feelings of insecurity

- mistrust

- avoidance of contact/emotional comfort

- school refusal.

Children will have their ‘ups and downs’ so it would not be particularly concerning for a child to experience some of these listed issues on any given day. However, when a child is experiencing several of these issues on a regular basis, and they are negatively impacting on their functioning, then a full assessment of their mental health is warranted. A child’s SENCO can help in arranging for such an assessment, or a parent can request that the child’s general practitioner refer the child for an assessment at the local CAMHS.

5.4 ‘Triggers’ for children’s anxiety in early childhood and school settings

In the following section, you will look at some of the situations that can trigger anxiety for children when they are in educational settings.

Transitions and changes of routine: For many young children, moving from their home environment to an educational setting for the first time can be challenging but exciting. For some children, however, the experience may be overwhelming and difficult to accomplish. For example, children who do not have a stable family life may not be able to cope with the demands and expectations that are placed on them when they start school. Conversely, some children have a very supportive home and family environment and they struggle with starting school. They may not feel as emotionally prepared for the change as some other children. Behaviour that is acceptable at home may not be in a more formal setting. If young children are better prepared for such discontinuities, and the different expectations between the two environments are more openly discussed between parents, children and school staff, then more effective bridges between home and school can be created.

Children on the autistic spectrum may find changes to their normal routine problematic, as they will find it more difficult to feel they have a sense of control as to what is happening; consequently, starting school may ‘unbalance’ them. As a result, these children might increase some of their obsessive and/or repetitive behaviours as a way to block out the chaotic, unpredictable and ‘noisy’ environmental sounds and movements, as this can help them cope with the extra (unwanted) stimulation.

Both schools and carers have a responsibility to ensure that transitions happen as smoothly as they can, with good links made between home and school as early as possible. At times, for children with additional needs, these transitions require creative solutions (e.g. reduced hours to start with) and agile problem-solving (when things do not go as planned). Good practice to help children feel a greater sense of belonging and emotional security also highlights why the role of the key person in early years settings is so critical. You will look at this further in Session 5.

Bullying: Bullying, rejection from peers and teasing can be widespread wherever children engage in groups. It is not always easy for adults to understand the huge distress that bullying can cause children, especially when it involves what adults may see as low-level examples such as making fun of each other and intermittent teasing. However, when teasing becomes targeted and persistent, the child may feel extremely unhappy, especially when there is no escape from cruel and relentless judgements about themselves and the bullying goes unpunished. Thinking back to Session 1, where Bowlby’s theory of attachment was introduced, you looked at attachment and how children build relationships. The importance of children developing close, caring and positive relationships helps them to build up an effective internal set of ideas, or what has been called an ‘internal working model’ (Bowlby, 1969) of how they see themselves. If children receive consistently negative messages, this can feed into a child’s self-image of being less worthy and lead to them developing low self-esteem. The concept of internal working models will be looked at in detail in Session 3.

There are ways in which carers, schools and the local community can discourage bullying and encourage the growth of positive social relationships. You will look at this in more detail in Session 5.

Problems with the demands of school work: Even very young children can become frustrated, anxious or down if their attempts to meet the perceived standards of formal schooling (or what they think their parents want them to achieve) do not result in successful outcomes. They can then become so worried that ‘fear of failure’ stops them from completing work satisfactorily, or even ‘having a go’.

Often, the fears that a child has built up are worse than the reality of the situation (i.e. the anticipation is worse than the actual event). Helping the child to separate their thoughts and feelings from other people’s expectations can help. Also useful is working with the child to create achievable personal goals that they can monitor in some way themselves (e.g. using sticker charts).

Difficulties with teachers: In Session 3, you will explore how attachments between young children and significant carers evolve. Within these processes, teachers can be seen as potentially valuable secondary attachment figures as young children transition from home to school. However, sometimes children and teachers do not get on very well together and relationships can be strained or break down. In such circumstances, children might feel reluctant to go to school, develop psychosomatic illnesses (i.e. a mental health issue that manifests in physical form) to stay at home, growing highly anxious or becoming extra ‘clingy’ to parents/carers.

The key to resolving these issues is finding out from the child what it is about that particular teacher that is upsetting them, and seeing whether a more positive relationship can then be restored through negotiation between the family, teacher and child.

Socialising or group work: For some shy and anxious children, being part of a large group can be extremely intimidating. There can be the fear of being ‘shown up’ in front of others; therefore, these children might avoid answering questions in class. There can also be high levels of anxiety around performing tasks, even within a smaller group, for fear of ‘getting it wrong’ or ‘being made fun of’. Such anxiety is not just limited to the classroom but can be made even worse in a large playground situation at break times. The solution for some children is to walk around with the teaching assistant or teacher on duty and avoid taking part in games or activities with other children. Unless such social anxiety is tackled early on, and the child gradually supported to join in with other children using a step-by-step approach, then the avoidance can become so ingrained that any social situations can become extremely agonising as the child gets older.

6 Personal reflection

At the end of each session, you should take some time to reflect on the learning you have just completed and how it has helped you to understand more about children’s mental health. The following questions may help your reflection process each time.

Activity 3 Session 2 reflection

- What did you find helpful about this session’s learning and why?

- What did you find less helpful and why?

- What are the three main learning points from the session?

- What further reading or research might you like to do before the next session?

7 This session’s quiz

Well done – you have reached the end of Session 2. You can now check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window and come back here when you have finished.

8 Summary of Session 2

In this session, you’ve seen that a child’s mental health will fluctuate, and that very young children have the added difficulty of their inexperience which may mean they are unable to recognise, articulate or make sense of their own feelings. Children’s cognitive, social and emotional development is a process, just like any other aspect of their development. You’ve also seen that physical health conditions can have a detrimental impact on children’s emotional wellbeing and mental health, as demonstrated in the case study of Charlotte.

You should now be able to:

- appreciate that children’s mental health can vary for individuals and over time

- describe some of the common mental health conditions that affect children

- understand some of the factors that are associated with mental ill-health in children

- explore some of the effects of poor mental health and illness on children’s education and development

- identify ‘triggers’ for anxiety in children.

In the next session, you will look at the ‘ingredients’ of good mental health and wellbeing for young children.

You can now go to Session 3.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Jackie Musgrave and Liz Middleton. It was first published in October 2020.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Images

Figure 1: Tokarchuk Andrii; Shutterstock.com

Figure 3: Eakachai Leesin; Shutterstock.com

Figure 4: jennylipets; Shutterstock.com

Figure 6: fizkes; Shutterstock.com

Figure 7: Photographee.eu; Shutterstock.com

Figure 8: New Africa; Shutterstock.com

Figure 9: Cheryl Casey; Shutterstock.com

Figure 10: theshots.co; shutterstock.com

Figure 11: Ruslan Ivantsov; Shutterstock.com

Figure 13: ann131313; Shutterstock.com

Figure 14: CokaPoka; Shutterstock.com

Figure 15: Andrew Angelov; Shutterstock.com

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University.