Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 21 November 2025, 8:54 AM

Session 5: Wellbeing and mental health in education settings

Introduction

Around the world, many countries have developed national curricula for pre-school and school-aged children. Each curriculum includes principles aimed at improving children’s emotional and social development. Implementing these aims means that practitioners and teachers have an increasingly important role in creating an environment that is conducive for children to develop good mental health and wellbeing.

In this session, you will explore some of the ways that educators in pre-school and primary school settings are approaching this responsibility. You will discover how the ethos of the early childhood and/or school setting is critical to children’s wellbeing. For example, routines such as circle time (i.e. where the pupils and teacher come together in a physical circle to learn) that are embedded in practice can help adults to listen to children, and are important strategies for the development of good wellbeing and positive mental health.

In this session, you will explore how developing and implementing policies relating to anti-bullying and safeguarding can contribute to improving the mental health of children. Finally, you will consider the significance of play throughout a child’s life in promoting good mental health and wellbeing.

Now listen to the audio introduction to this session.

Transcript: Audio 1

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- explore ways to promote positive wellbeing through the curriculum in early years education settings and primary schools

- be aware of the critical role of the key worker/person in early care and education settings

- consider the role of whole school approaches to promoting wellbeing in early years and in primary schools

- reflect on the role of policies in the prevention of mental health issues.

1 Promoting wellbeing in young children’s care and education

As you have seen in previous sessions, there are many factors and resources within children’s lives that can make a positive contribution to their mental health. Education and care settings can provide an ideal environment for children to develop a good sense of wellbeing. And for children who are experiencing negative factors in their lives and have fewer resources available to support them, a pre-school or school setting can be a place of refuge. Well-ordered daily routines that are aimed at addressing and meeting all children’s needs, as well as policies and practice aimed at delivering high-quality care and education, play an important role in promoting positive wellbeing.

In much of this session, you will explore some of the strategies embedded within curricula for pre- and school-aged children that are aimed at supporting children’s wellbeing.

In the next section, you will look at how such strategies are embedded in pre-school curricula.

2 Early years education and care curriculum

Many high-income countries have a curriculum specifically designed for the care and education of infants and pre-school children. In 1996, New Zealand was one of the first countries to create its curriculum for the education and care of very young children, known as ‘Te Whāriki’. This is a Māori expression meaning ‘the woven mat’. The New Zealand vision of Te Whāriki is outlined in the curriculum guidance as follows:

Te Whāriki is underpinned by a vision for children who are competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society.

The Te Whāriki document goes on to emphasise the importance of developing good wellbeing in children by promoting their sense of belonging, providing routines and giving opportunities for communication. The four nations of the United Kingdom have each introduced their own early years curriculum:

- England: in 2007, the Early Years Foundation Stage was introduced, setting the standards for learning, development and care for children from birth to age five.

- Northern Ireland: in 2007, the Foundation Stage curriculum was introduced.

- Scotland: in 2006, Curriculum for Excellence was introduced.

- Wales: in 2010, the Foundation Phase was introduced.

The links to the current documents are listed in the ‘Further reading’ section at the end of the session.

In the same way that the New Zealand Te Whāriki curriculum includes principles that are aimed at developing good mental health, so do UK curricula. In the next section, you’ll examine some of the aims of England’s Early Years Foundation Stage.

2.1 Aims of the Early Years Foundation Stage

In England, the early years curriculum is the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS). The overarching principles for the EYFS are:

- every child is a unique child, who is constantly learning and can be resilient, capable, confident and self-assured

- children learn to be strong and independent through positive relationships

- children learn and develop well in enabling environments, in which their experiences respond to their individual needs and there is a strong partnership between practitioners and parents and/or carers

- children develop and learn in different ways.

The principle that each child develops and learns in different ways is important to bear in mind; however, the EYFS states that there are three characteristics of effective learning:

- playing and exploring: children being encouraged to ‘have a go’

- active learning: children concentrate and keep on trying if they encounter difficulties, and enjoy achievements

- creating and thinking critically: children have and develop their own ideas, make links between ideas and develop strategies for doing things.

If learning is planned to give opportunities for children based on the characteristics of effective learning, they will be able to experiment with alternative ideas and find strategies for doing things, either on their own or working with others. The notion of ‘having a go’ is linked with being persistent and this in turn helps to develop resilience. The concept of children exploring and experimenting at their own pace helps them to develop concentration. Creating learning opportunities for children that include these approaches helps them to develop a sense of achievement, which is linked to wellbeing.

Children’s wellbeing is therefore at the heart of the EYFS curriculum. In the next section, you will look at how positive relationships can help young children’s wellbeing, focusing on the role of the key person. The term ‘key person’ is used in the EYFS: the aim of the role is similar to the role of ‘key worker’.

The key person approach

The role of the key person is based on the work of Elfer, Goldschmied and Selleck (2003) and is a legal requirement of the EYFS statutory framework. The key person ensures that every child is designated a named member of staff who will ‘help the child become familiar with the setting, offer a settled relationship for the child and build a relationship with their parents’ (Department for Education, 2017a, p. 22, section 3.27).

The role of the key person is based on young children’s need to have sound attachments with adults. Such attachments can form the basis of a positive relationship, which can help children to learn to be strong and independent.

The key person needs to respond sensitively to the child’s feelings and behaviours. They need to reassure and support the child’s emotional needs and wellbeing as they transition to a new setting or class. This person should be someone who the child sees as a familiar and friendly person, who is accessible and understands how the child is attempting to make sense of their environment and the expectations that they encounter. As a result, the child is likely to feel more settled, happy and able to explore spaces and engage in activities more independently.

Activity 1 The benefits of the key person approach

What do you think are the benefits for a child in having a key person/worker? Make a note of your ideas.

Discussion

You may have included some of the following.

The key person/worker can:

- help their key child to develop positive and responsive relationships with staff and children

- help the child to have good quality interactions with other children and staff

- get to know the child very well

- create a welcoming environment for their key children and caregivers/parents

- know the key child’s likes and dislikes

- plan appropriate activities that reflect the child’s interests and help to promote development.

So, the role of the key person/worker is to get to know the child and their family or carers so that their needs can be met.

In the next section, you’ll look at wellbeing principles within curricula for school-age children.

3 Primary school-aged children’s mental health

In many countries, there has been increased understanding of the importance of promoting children’s social and emotional development, which, as you have already seen, can improve wellbeing and promote good mental health. This has resulted in strategies aimed at supporting children’s social and emotional development being embedded within school curricula.

In England, children in primary education are aged 4–11 and the National Curriculum for primary education includes statutory guidance relating to Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education (Department for Education, 2019). Is there an equivalent in Scotland?

The guidance states that at the end of primary school, in relation to their mental wellbeing, pupils should know the following:

- that mental wellbeing is a normal part of daily life, in the same way as physical health

- that there is a normal range of emotions (e.g. happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, nervousness) and scale of emotions that all humans experience in relation to different experiences and situations

- how to recognise and talk about their emotions, including having a varied vocabulary of words to use when talking about their own and others’ feelings

- how to judge whether what they are feeling and how they are behaving is appropriate and proportionate

- the benefits of physical exercise, time outdoors, community participation, voluntary and service-based activity on mental wellbeing and happiness

- simple self-care techniques, including the importance of rest, time spent with friends and family and the benefits of hobbies and interests

- isolation and loneliness can affect children and that it is very important for children to discuss their feelings with an adult and seek support

- that bullying (including cyberbullying) has a negative and often lasting impact on mental wellbeing

- where and how to seek support (including recognising the triggers for seeking support), including whom in school they should speak to if they are worried about their own or someone else’s mental wellbeing or ability to control their emotions (including issues arising online)

- it is common for people to experience mental ill health. For many people who do, the problems can be resolved if the right support is made available, especially if accessed early enough.

Activity 2 Mental health and wellbeing in primary school-aged children

Referring to the above extract about mental wellbeing from the Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education statutory guidance, consider the following questions:

- What are your thoughts about the expectations of children’s knowledge about mental wellbeing?

- What skills and qualities do adults working with children in education settings need in order to support children to achieve these aims?

- What can educators do to give children opportunities to gain this knowledge?

Discussion

You may have thought that the topics relating to mental wellbeing that children are expected to learn between the ages of 4 and 11 are extensive. You may also have noted that some of the topics relate to what you’ve explored in previous sessions. Some of the topics will be discussed in later sessions; for example, Session 8 looks at the internet and cyberbullying.

The topics may also have made you think that educational settings play a significant role in promoting opportunities for children to engage in activities that make them feel positive about themselves, which of course links to wellbeing.

An important skill that educators need to develop in order to be responsive to children is that of listening. The following sections explore why this is important, and ways of creating opportunities to listen to children.

4 Listening to children

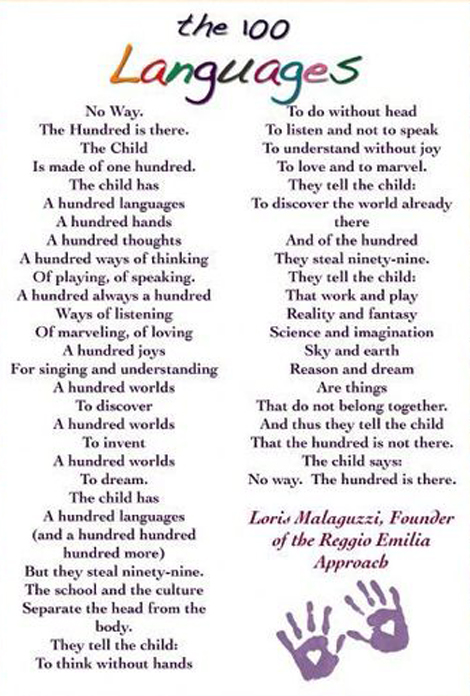

Listening to children is fundamental to understanding them; however, listening does not only mean hearing the words that children say. One of the pioneers of early education in Italy, Loris Malaguzzi (1920–94), was very attuned to the fact that children have many different ways in which they communicate their thoughts and feelings. He put together the following poem to express what he perceived as the 100 languages in which children attempt to express themselves if only adults could learn to listen attentively:

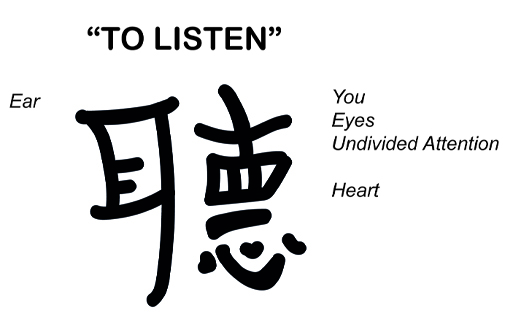

At this point, you might also note that the Chinese symbol for listening is as follows:

So, the verb ‘to listen’ moves beyond simple notions of ‘hearing’. Actions include using your eyes to observe; in this case, giving the child your undivided attention while you also open your heart and your mind to what the child is communicating to you.

Activity 3 Listening to children

In the following video, practitioners talk about their involvement in a listening project in an early years setting. Watch the video then consider the questions that follow.

Practitioners in an early years setting

- What is the importance of listening to children?

- What can the process of listening involve when we go beyond simply using our ears to hear?

- How does the poem you read about the 100 languages link to aspects of listening to children that the staff in the video mention?

- How do issues in the video relate to any previous work you have done in this course?

Discussion

You may recall staff talking about how they have found themselves increasingly open to all the different ways that children express themselves, and that listening goes beyond simply hearing what the young child says. Listening is as much about close and attentive observation, waiting patiently and the imitation of physical gestures, but wherever possible with the child leading the process.

You probably took note of two important processes that you have previously considered: attachment and attunement, which were in Session 3. You will come across these processes again when you examine the role of the counsellor in Session 7. Communication with the child and being finely attuned to everything they do helps to form effective social and emotional attachments.

The key component of listening to the whole child is for the process to be child-led. By observing and listening, adults can build up a much richer picture of the child and how they experience the world in which they live. In the broadest sense, listening can help to promote good wellbeing.

In the next section, you will explore one example of a practical way that adults in educational settings can listen to children.

4.1 Practical ways of listening to children: circle time

Creating opportunities to listen to children is an important way of developing confidence. One example of such an opportunity is circle time.

Circle time can be used in pre-school or primary school settings and is an approach that can help children to have their voice heard in a group. Doing so can help to develop and boost children’s self-esteem.

Circle time can help to foster positive and effective social relationships between children. At its heart is the time set aside to enable adults and children to join in activities that help to promote a sense of belonging within a safe emotional space where feelings can be explored and experiences shared. Circle time can help to improve children’s social and emotional skills.

In the next section, you will look at the importance of play and creativity in promoting children’s wellbeing.

5 The importance of play and creativity in promoting children’s wellbeing

In Session 4, you considered the importance of children’s rights. One of those rights is the right to play.

Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) states that all children (from birth) have the right to ‘rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts’ (UNICEF, 1989, p. 10).

The right for children to be able to play has influenced many of the early years curricula that you have looked at earlier in this session.

While early years curricula focus on play as a vehicle for children’s learning, the importance of play and creativity in primary education is sometimes not regarded as being as important. However, it is essential that all children have opportunities to engage with different types of play and that they have creative opportunities.

6 Promoting good mental health in primary education

As you saw in Session 3, the old saying that ‘prevention is better than cure’ is especially relevant to developing wellbeing and preventing mental health problems. In primary education, there are many initiatives aimed at promoting wellbeing. In the next section, you will explore how taking a whole school approach is important to achieve this aim.

6.1 A whole school approach

Glazzard and Bostwick (2018) outline how schools can address mental health through the curriculum as a way of reducing stigma and increasing pupils’ knowledge about topics including anxiety, depression, self-harm and resilience. As well as increasing knowledge, an aim of the whole school approach is to help children to develop strategies that help them to reduce the impact of factors or feelings that may impact negatively on their mental health. In addition, children are encouraged to be aware of and sensitive to other peers who may be experiencing such difficulties.

The curriculum of a school that is taking a whole school approach to promoting positive mental health includes opportunities for children to engage in play, physical activities, art, music, dance and drama. It is also important to include opportunities for discussions about gender and identity, race and ethnicity, religion and belief systems as well as disabilities and their impact, which can inform children about difference. By doing so, children who feel ‘different’, perhaps because of a disability for example, may feel a greater sense of belonging.

Developing effective policies that are aimed at addressing children’s wellbeing and mental health is a way that schools can work together and take a whole school approach. Policies relating to children’s wellbeing and mental health are discussed in the next section.

7 Policies to improve children’s mental health and wellbeing

You’ll now move on to how national government and local policies in educational settings can support children’s health and wellbeing.

7.1 Government policy

In addition to curriculum policy, since 2010, successive UK governments have pledged to improve support for children’s mental health. Here are some of the main policies.

The following is a summary of key policies in England taken from a House of Commons Briefing Paper, Children and young people’s mental health – policy, services, funding and education (Parkin, Long and Gheera, 2020).

- The Future in Mind taskforce report (Department of Health and Social Care, 2015) set out ambitions to improve mental health.

- The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health (NHS Mental Health Taskforce, 2016) includes specific objectives to improve treatment for children and young people by 2020/21.

- The Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision Green Paper (Department of Health and Department for Education, 2017), which was published jointly by the Department of Health and the Department for Education. Two of the main aims will require schools to designate a senior lead to oversee the approach to mental health and wellbeing, and to fund mental health support teams that are supervised by NHS staff that will be linked to schools.

- The NHS Long Term Plan (NHS, 2019) restated the Government’s commitment to deliver the recommendations in the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health and set out further measures to improve the provision of, and access to, mental health services for children and young people.

- The Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education (Department for Education, 2019) guidance is part of the National Curriculum in England and has been discussed in Section 2 of this session.

Government policies at national level are aimed at providing guidance about the services that are required to respond to the mental health needs of young children. However, policies at local level in education settings can also make a positive contribution to improving children’s mental health.

7.2 Policies in settings

Early years and school settings have many policies that cover a wide range of issues. Policies that relate to health and wellbeing are likely to address mental health. However, there are other policies that may not appear to be directly linked to wellbeing.

Activity 4 Policies that help to support children’s mental health

- List the policies in an education setting that you think can help to support children’s mental health.

- Give a brief explanation of why and how the policy can help to support children’s mental health.

Discussion

You may have thought of the following:

- behaviour management

- safeguarding

- anti-bullying interventions.

The following sections explain the ways that these policies can help to support children’s mental health.

Behaviour management

Children’s emotions are linked to their wellbeing and mental health. In a pre-school or school setting, there are many triggers for children to become highly emotional; for example, other children taking their toys, being asked to stop an enjoyable activity or simply being tired or hungry. As you saw in Session 2, understanding children’s development can help adults to appreciate that children’s reactions can vary depending on their age and stage of development. Knowing the circumstances of the child and their family can also help adults to understand the reasons why children behave in the way they do.

Young children need a calm and consistent response from the adults around them. For this reason, education settings will have a behaviour policy written by staff in the setting.

Ideally, policies should be written with input from all staff because this helps to develop a shared understanding of the behavioural issues (and expectations) that are relevant to the children in that specific setting. More recent initiatives regarding creation of policy and putting such policy into practice highlight the need to actively involve children in such decision-making from an early age so that, as rights holders, they can have a genuine say in the expectations, rules, routines and practices that affect their daily lives. Involving young children in a more active role as part of democratic decision-making processes can also help them understand what active citizenship entails. Including all stakeholders in writing policies is an example of a whole school approach.

Safeguarding

Safeguarding children and preventing abuse is important for many reasons, including that childhood abuse can lead to poor mental health.

Therefore, by being aware of the safeguarding policies in their setting and implementing them effectively, all adults who work with children can contribute to the prevention of mental health issues not only in childhood, but across the age span.

Anti-bullying

Many schools’ bullying policies are aimed at responding to bullying once it has started. However, preventing and tackling bullying is an effective way of improving children’s mental health and wellbeing (Brown, 2019).

Examples of anti-bullying strategies that can be part of a school’s policy include the use of circle time, peer group councils and buddy schemes for pupils who are at risk of being bullied. Whole school approaches can include anti-bullying assemblies and a week dedicated to activities linked to anti-bullying.

For more information about the government’s guidance for schools, see ‘Preventing and Tackling Bullying’ (Department for Education, 2017b).

On page 8 of the guidance, bullying is defined as follows:

Bullying is behaviour by an individual or group, repeated over time, that intentionally hurts another individual or group either physically or emotionally. Bullying can take many forms (for instance, cyber-bullying via text messages, social media or gaming, which can include the use of images and video) and is often motivated by prejudice against particular groups, for example on grounds of race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, special educational needs or disabilities, or because a child is adopted, in care or has caring responsibilities. It might be motivated by actual differences between children, or perceived differences. Stopping violence and ensuring immediate physical safety is obviously a school’s priority but emotional bullying can be more damaging than physical.

You have seen how policies that do not appear to be directly linked to supporting children’s wellbeing and improving their mental health can be instrumental in doing so. You may also have thought of other policies that could help to support children’s wellbeing.

By adopting a whole school approach where there is a supportive ethos and an environment where children can flourish, much can be done to prevent mental health problems from developing. However, some children will inevitably require further interventions, as you will see in the following section.

8 Early interventions: going beyond preventative

Much of what you have explored so far has highlighted the importance of creating an environment for children that is conducive to good wellbeing. However, there will be times when children are adversely affected by what is happening in their lives and require additional support. By offering an early intervention, it is possible to reduce the impact of events on children’s mental health. Examples of interventions that are aimed at improving children’s wellbeing include mindfulness and relaxation activities. In many schools, nurture groups are also used. In the next section, you will focus on the role of nurture groups in primary schools.

8.1 Nurture groups in primary schools

Nurture groups are increasingly being used to offer short-term support to children who are experiencing social and emotional difficulties. Nurture groups are described as:

The classic model for Nurture Groups involve classes of about 10–12 children, typically in the first few years of primary school, and staffed by a teacher and teaching/classroom assistant. The aim of the Groups is to provide children with a carefully planned, safe environment in which to build an attachment relationship with a consistent and reliable adult.

In Northern Ireland, the Department of Education funds nurture groups, and in the evaluation of nurture groups carried out by Queen’s University, they state:

This evaluation found clear evidence that Nurture Group provision in Northern Ireland is highly successful in its primary aim of achieving improvements in the social, emotional and behavioural skills of children from deprived areas exhibiting significant difficulties.

Part of the aim of nurture groups and other early intervention approaches is to give children opportunities to develop resilience, but what is this and why is it so important for good mental health?

8.2 Developing resilience

As you saw in Session 2, resilience is the ability to recover, or bounce back from adverse experiences. This means that we have a go at doing something and if we don’t succeed the first time, we try to achieve the same goal, but perhaps approach it in a different way.

Children can develop emotional resilience following exposure to risky or stressful events; however, their ability to ‘bounce back’ is increased with support from those around them. So, if children develop resilience when faced with exposure to risk and stress, it follows that if they are protected from all such events (i.e. they are ‘wrapped in cotton wool’), they may not have opportunities to develop emotional resilience.

However, it is not only emotional events that can help to build resilience. Giving children opportunities to take part in risky play helps to build resilience because they learn to assess risks.

9 Personal reflection

At the end of each session, you should take some time to reflect on the learning you have just completed and how it has helped you to understand more about children’s mental health. The following questions may help your reflection process each time.

Activity 5 Session 5 reflection

- What did you find helpful about this session’s learning and why?

- What did you find less helpful and why?

- What are the three main learning points from the session?

- What further reading or research might you like to do before the next session?

10 This session’s quiz

Well done – you have reached the end of Session 5. You can now check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come here when you’ve finished.

11 Summary of Session 5

In this session, you’ve focused on how pre-school and school curricula can support young children’s wellbeing and mental health.

You should now be able to:

- explore ways to promote positive wellbeing through the curriculum in early years education settings and primary schools

- be aware of the critical role of the key worker/person in early care and education settings

- consider the role of whole school approaches to promoting wellbeing in early years and in primary schools

- reflect on the role of policies in the prevention of mental health issues.

In the next session, you will explore how professionals in health, education and social sectors can work together to support children’s health and mental wellbeing.

You can now go to Session 6.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Jackie Musgrave and Liz Middleton. It was first published in October 2020.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

Figure 1: FatCamera; Getty Images

Figure 2: yaruta; Getty Images

Figure 3: Weekend Images Inc.; Getty Images

Figure 4: Lokibaho; Getty Images

Figure 5: skynesher; Getty Images

Figure 6: Loris Malaguzzi; taken from https://reggioemilia2015.weebly.com/ the-100-languages.html

Figure 8: SDI Productions; Getty Images

Figure 9: davidf; Getty Images

Figure 10: Mykhailo Polenok; 123rf.com

Figure 11: DGLimages; Getty Images

Figure 12: energyy; Getty Images

Figure 13: monkeybusinessimages; Getty Images

Figure 14: Hakase_; Getty Images

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.