Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 5:50 PM

Session 7: Exploring some of the interventions to support children’s mental health

Introduction

In the last session, you looked at some of the roles of different professionals and the processes that relate to facilitating children’s mental health and wellbeing within the child’s community. This session, you will be looking in more depth at several of the other therapeutic approaches that might be used by practitioners such as therapists and counsellors. You will also watch a video demonstrating how engaging playful activities are used with younger children and how these can be adapted as forms of therapeutic occupation or activities.

You will be introduced to the ways that specially trained dogs are used therapeutically in non-clinical settings and what the positive advantages of this creative approach might be. You will also have the opportunity to reflect on the use of medication to treat some mental health conditions, in particular attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In addition to this, you will explore behaviour management through the use of a particular toolkit and re-examine the role of schools, parents and wider organisations in helping to support children’s mental health and wellbeing.

Now listen to the audio introduction to this session.

Transcript: Audio 1

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- recognise how the power imbalances between child and adult can affect the therapeutic processes

- understand what is meant by cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

- appreciate the role of play and creativity in counselling and therapy with young children

- realise some of the challenges associated with prescribing medication to treat a child’s mental health condition

- understand how parents might be helped to manage children’s behaviour and support their wellbeing.

1 Counselling and therapy

One of the issues to be aware of around counselling and all other talk-based therapy is how terms are used by a range of professionals across numerous different contexts. For example, teachers and support workers in schools and in the social care services may well use counselling micro skills very effectively (e.g. active listening and paraphrasing). However, they will not be trained counsellors or registered health professionals, which include specialists like clinical psychologists who have had extensive therapy training, often to doctoral level. In order to be an accredited counsellor or psychotherapist specialised in working with children, you need to have completed training approved by the British Association of Counsellors and Psychotherapists (BACP). Other therapists, for instance practitioner psychologists (which include clinical psychologists), occupational therapists, and art therapists (specifically music, dance and drama therapists) have completed accredited training to at least degree level and are registered by the Health and Care Professions Council.

1.1 Adult–child power imbalance

When working with children in any therapeutic way, adults should be aware that children often come into therapy through referral by other agencies and carers, as you have seen in Session 6. They are therefore not necessarily entering into the relationship with a therapist through their own choice, but because adults feel they would benefit from the process.

Children are not emancipated adults and as such they will always be part of a system which includes carers (usually their parents and other family members) and professionals (especially teachers) who make decisions on their behalf, often without sufficient negotiation with the child themselves. This means that the child can struggle to understand what is going on, especially in the case of a referral to CAMHS where the child is unaware of the depth of concern the adults in their life have about them. For example, young children are not always perceived as being competent enough to make important decisions, even around their lived experiences, but being unaware of a CAMHS referral can mean that they struggle to engage in their initial assessment, because they may incorrectly assume they are being seen in CAMHS as part of a punishment. Furthermore, children are developing and, despite being extremely adaptable as well as capable in many respects, they are emotionally vulnerable, especially if they have had to deal with complex challenges in life such as trauma.

So, adult–child relationships within therapy can still mirror power imbalances and potential misuses of power (including abuse for some) that children may well have endured prior to entering therapy. For this reason, therapeutic work with children needs to be undertaken skilfully by suitably qualified personnel with appropriate safeguards in place to protect the child.

2 Cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a widely used evidence-based form of treatment that is used with children and adolescents, and is delivered in a developmentally appropriate way to fit with individual children’s needs in terms of their cognitive, social and emotional skills.

2.1 Aims of cognitive behavioural therapy with young children

CBT works on the basis that an individual’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours are all interrelated. For instance, a child might struggle to manage negative (or maladaptive) thoughts, such as ruminating about their parents dying in a volcanic eruption in the UK (where these eruptions are unheard of) which then results in the child feeling sad and anxious, to the point where they frequently become tearful. This in turn results in ‘extra clingy’ behaviour where the child can even become aggressive when their mother tries to leave them for fairly short periods of time. CBT, after a thorough psychosocial assessment, would then involve supporting the child to develop more positive (or adaptive) thoughts that challenge the ruminations as well as skills (such as controlled breathing) while working with the child’s parents to employ behavioural strategies to treat the child’s anxiety.

The process usually involves a therapist working regularly with an individual child (perhaps weekly or fortnightly) often for an hour over a number of sessions. The main aim is to help modify or replace existing ‘faulty thinking’ and unhelpful behaviours, which in turn help to improve a child’s mood and improve their functioning, hence resolving or lessening the presenting problem. The focus in CBT is therefore centred on the present rather than working through an individual’s earlier life experiences (as might happen in other forms of psychotherapy).

Implementing CBT in practice

The implementation of CBT in practice involves three key stages: assessment; intervention and evaluation (Zandt and Barrett, 2017).

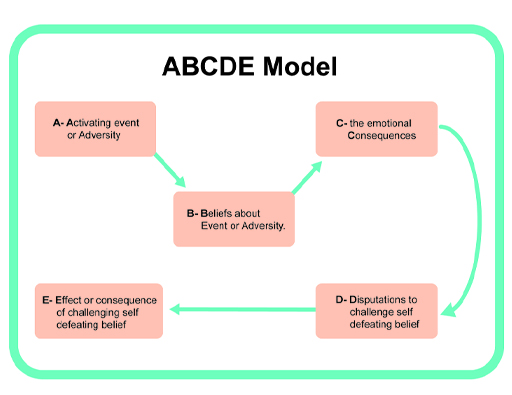

The ABC model is often used at the initial assessment stage as a means to make sense of the presenting issues.

- A being the activating event (i.e. what seems to trigger the behaviours/responses)

- B being the individual’s belief system or attitude in relation to the event

- C being the consequences as reflected in behavioural or emotional reactions.

The key idea behind CBT is that when faced with any external event we can change our thoughts, feelings and behaviours, although this is not always easy to do, and that is why so many people have benefited from CBT as a form of therapy. As a result, we can challenge how we perceive events and look at alternative and potentially more helpful ways to view our experiences.

As part of intervention, steps D and E are included (as shown in Figure 3):

- D being the challenges/questions around the more negative, self-defeating belief

- E being the effect of challenging previous attitudes and beliefs.

To help illustrate how CBT can be applied in practice, you will first be asked to think about a case study of an adult before thinking about psychotherapy with children. Any new ways of dealing with the problem that have been put into place and practised are evaluated to see how effective they have been. For example, this will include whether there have been changes in any interactions, how the person is now feeling and how they currently see themselves.

Activity 1 The ABCDE model in practice in adults

Sam has been having problems at work over a number of months (Activating event) and things feel like they are getting worse. As a result he is feeling very low, tired and irritable (Physical and Emotional Consequences). As a result he has been avoiding people, especially his usually supportive family (Behavioural Consequences) who tend to be ‘stiff upper lip’ sorts. He comes home one day, after a tough day at work, when he is feeling especially low and tries to talk to his wife, Amy, about what has been going on for him.

Amy seems preoccupied and Sam gets angry (Emotional Consequence). He thinks ‘No one ever cares about me or has time for me’ (‘All or nothing’ self-defeating/negative Belief).

How do you think Sam might start to challenge his negative thinking (step D)? What questions could he start to ask himself?

How might any of the responses to his questions help him to change his initial thinking (Step E)?

Discussion

You might have thought of some of the following in relation to questions and the ABCDE model:

- When did the issues at work begin? Was there a particular trigger or event?

- What appears to make things better or worse? Has Sam noticed improvements in his mood on, say, a Friday night (i.e. leaving work for the weekend)?

- Carefully consider the evidence. Who are the people that Sam cares about? How likely is it that none of these people care about him?

- How does he know that Amy was ‘preoccupied’, and how has their relationship been more generally since he has been avoiding family members?

- Who has he tried talking to about his problems so far and how does he usually go about communicating his feelings to others?

- Why might Amy be preoccupied and what has helped him and Amy to communicate about important matters in the past?

If we delve more deeply into our own negative thinking and the automatic responses and conclusions we can reach, we are more likely to find alternative ways to solve our problems. We can gently interrogate ourselves to see if our original thinking holds true.

CBT techniques can work in a similar way with older children and adolescents, using worksheets or other resources to help them to make sense of the problems they are encountering. They can talk and draw diagrams to help explain what is happening for them in different contexts and begin to understand more about how and why they react to certain triggers. They can then learn to find alternative ways to think about their problems and create their own solutions with the adult guiding them along the way.

However, how is such a focus on the way feelings, thoughts and behaviours are linked together possible with young children, who are perhaps not able to express their thoughts or feelings verbally?

In adaptations of CBT for use with children, play is used in various activities to help explain some of the issues in a simpler and more meaningful way. For example, through an activity such as using a pair of coloured glasses to look at different objects, a child can begin to understand how we might ‘distort’ things ourselves when we experience certain situations.

3 Play therapy

Play is, in effect, a symbolic language: a means of communication by which children can express themselves without necessarily having to use words. Through play, children can communicate their understandings and stories about their worlds and reshape their experiences as a natural way of recovering from daily emotional upheavals. Play can therefore have a very powerful therapeutic effect as a vehicle that trained personnel can use to help channel thoughts and emotions, including in very distressed young children.

Through play therapy, the practitioner enables both a structure to the session as well as the creation of a ‘safe space’ to work through powerful emotional reactions. The practitioner (such as a counsellor) will carefully observe the objects the child chooses to use in their play, the ways in which they use these objects and how the child interacts with the counsellor through play.

3.1 Play therapy in action

Children often find it easier to talk while they are playing. In a play-based therapy a practitioner uses a range of toys, books or other activities as a way of encouraging children to communicate their feelings and thoughts. The therapist will listen and observe the child during a play therapy session. In Session 5 you examined the importance of listening to children, the points covered included:

- the importance of listening to the ‘whole child’, not just what they say verbally

- keeping the child at the centre of the listening process

- allowing the child to take the lead

- how listening was related to the processes of attachment and attunement.

Attunement can be perceived as the art of reading body language, reading what the child is doing in their attempt to communicate with us. As adults, we need to feel open to what children are saying, demonstrating and expressing. Then we can affirm what they have said by repeating their expressions and body language so that we are ‘in tune’ with what they want us to see, rather than what we think we want for or from them.

Activity 2 Counselling children through play therapy

As you listen to Christine (who is a play therapist) in the following video clips, consider how she is explaining the art of listening to children and how she allows the child to take the lead in the counselling process.

You might want to watch all the video clips at once or just dip into each as and when you want to.

Transcript: Video 1

Transcript: Video 2

Transcript: Video 3

Transcript: Video 4

Transcript: Video 5

Transcript: Video 6

Transcript: Video 7

Transcript: Video 8

Transcript: Video 9

After watching the video clips, note your responses to the following questions:

- How would you describe the key aspects of the counsellor’s approach to working with children explained in the videos?

- In what ways does Christine suggest her role is different from other adults who might be supporting children?

- What processes were described in each of the three counselling phases Christine mentioned?

- How did Christine explain the ways in which she uses her therapy dog, Sammy?

- Which activities demonstrated by the counsellor interested you the most?

- Why do you think that was?

- How do you think children would respond to the different activities?

Discussion

In the video clips you will have noticed how Christine, the counsellor, stresses how she keeps the child at the centre of her focus and is very much guided by what the child chooses to do. Christine’s role is more of a ‘watchful presence’, allowing the child to explore their environment and their feelings and reactions while she ‘actively listens’ to what they can share with her. These processes may well remind you of the role of the adult listening to children in early years’ settings, as you explored in Session 5.

4 Art therapy with refugee children

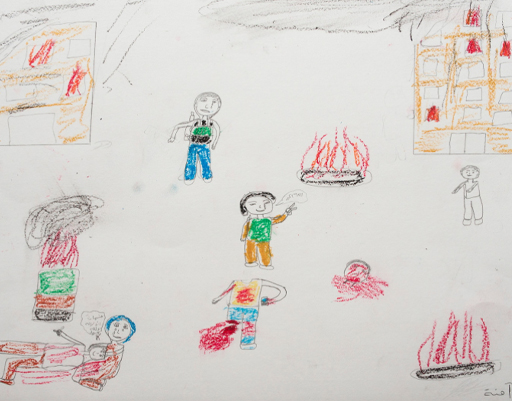

Creative art-based therapies are increasingly being used to help refugee children traumatised by the effects of conflict and crisis to express their feelings and narrate their own experiences (Tyrer and Fazel, 2014).

As you heard from the counsellor in Activity 2 and elsewhere in the course, art materials and creative processes can allow children to come to terms with emotional conflicts, develop greater self-awareness and social skills and encourage more effective coping strategies. They can help to increase self-esteem, reduce anxiety and enable children to learn various problem-solving skills.

Can you also see how use of such materials and therapy with refugee children might help them feel a sense of control over their environment, and enable them to reform a sense of who they are after experiencing the multiple losses that you read about in Session 4?

A qualified art therapy is a more recent intervention in places like Lebanon. Here is a link to a news feature about some of the positive work that is being done with children and their parents there:

News Feature on use of art therapy in Lebanon (make sure to open the link in a new tab/window)

You will notice how parents are being encouraged to mirror their child’s drawings as a way of becoming more attuned to what their children are attempting to express about the experiences they have had.

5 Medication

For some children who have been diagnosed with selected mental health conditions, the symptoms may best be managed by introducing medication. Medication in the field of child and adolescent mental health is almost always recommended to be used in combination with other interventions, such as evidence-based psychotherapies like CBT. The decision to prescribe medication is a significant one and is usually only considered after a thorough assessment and when other interventions on their own are not making a sufficient difference to the child’s symptoms. Medication is prescribed by a medical doctor, usually a child or adolescent psychiatrist working in CAMHS, and the decision to do so should be in consultation with the child and their parents or guardians, frequently with input from other professionals involved in the child’s care.

Prescription of medication is limited in the child and adolescent mental health field, but when used it is important that the child is reviewed regularly to assess for possible side effects as well as improvements. For example, an older child with moderate or severe and persistent depressive symptoms may be prescribed an anti-depressant frequently alongside other interventions (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2019).

The most common conditions in the child and adolescent mental health field where medication is prescribed are for severe ‘treatment resistant’ depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and (in older adolescents and adults) psychosis.

It is important to note that there is varying guidance about the prescribing of medication for very young children; some medication is not licensed for children below a certain age. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) is part of the Department of Health in the UK and it produces guidance that is based on evidence about a wide range of health treatments and approaches to management.

Further information about prescribing medication for children with mental health conditions can be found in NICE guidance. You can find the details of some of this guidance in the ‘Further reading’ section at the end of the session.

5.1 The pros and cons of medication

There are of course pros and cons relating to the administration of drugs to manage symptoms of mental ill-health. Some medication is not prescribed, but are still ‘psychoactive drugs’ (i.e. is a chemical substance that changes brain function) nonetheless. For instance, when parents give their children ‘natural remedies’ such as St John’s wort, usually without any medical advice.

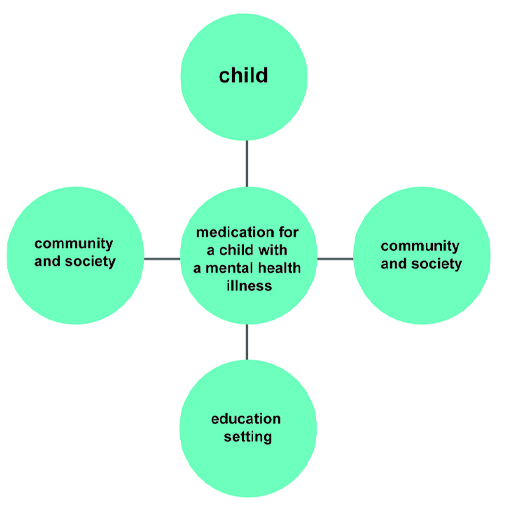

Activity 3 The advantages and disadvantages of medication for children with mental illness

Consider the pros and cons, or advantages and disadvantages, of prescribed medication when recommended by a medical doctor for a child who has been diagnosed with a mental health illness. Think about the possible advantages and disadvantages for the child, the family, their education setting.

Discussion

Here are some of the advantages and disadvantages of prescribing medication. You may have identified others.

The child

Advantages: Prescribing medication can help to address symptoms or features of a disorder and enhance a child’s functioning. For example, a child who has been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) after a comprehensive assessment across a range of environments, including their home and school, may find that medication, in particular Ritalin, can help to reduce their impulsive behaviour. Burton et al. (2014) illustrate this point by recounting their experience of working with children who report that an advantage of taking medication in this context is that it gives them ‘thinking time’ (p. 30), meaning that the medication can help increase their concentration. Increased concentration can help children to better engage with their education and learning.

Disadvantages: Not all medication works in the same way, and for some conditions efficacious medications are not available. Plus, we are all individual and dosage and personal preferences are important. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for medications to cause side effects. This is why, prior to being prescribed a medical doctor will do a careful ‘cost-benefit analysis’ to determine whether the possible advantages (or benefits) clearly outweigh the costs (such as the side effects). Children who have been prescribed medication for ADHD may experience sleep problems, headaches and mood swings (National Health Service, n.d.). But without their medication they may struggle to function adequately, disrupting their learning and negatively impacting on their relationships with others.

When medication is having a positive impact there are also disadvantages. A compromise may be reached by introducing what Pavord et al. describe as treatment ‘holidays’ (2014, p. 30). This is where, for example, the child may take a break from medication when they are not at school.

Parents

Advantages: Having a child with a mental health condition can be distressing for parents and the whole family. The symptoms of a mental illness can have a profound impact on parents, who frequently blame themselves for their child’s diagnosis, which can be difficult for them to manage. Prescribing medication occurs infrequently with younger children, and should always be done when it is in the best interests of the child. Reducing symptoms and improving functioning as a result of medication can mean that parents will experience less pressure and in turn it makes parenting a ‘challenging child’ less difficult. Reducing the pressure on the family can help make a positive contribution to the wellbeing of parents and other siblings.

Disadvantages: Parents may find that medication, in particular the treatment adherence associated with it, becomes an added task which requires extra effort and time. This can include remembering to order the medication, administering it suitably, liaising with the child’s education setting and taking the child to review appointments. Some parents may have cultural or religious beliefs that mean they are reluctant for their child to receive medication, and many parents will be opposed to their child taking medication because they would prefer talk-based therapy.

Education

Advantages: If the medication assists the child, in terms of their functioning, this can mean that the child is able to more fully participate in their education setting. This has advantages for the child, and potentially for other children and for the staff.

Disadvantages: Staff may need to be aware of potential side effects of medication. Learning about this will require time to access training and to be able to liaise with parents. Some medication is formulated so that it can be given at home; however, this may not always be the case, therefore a medication policy will need to be written. Consideration will need to be given about the storage and administration of medication and who at the school is responsible for this.

Prescribing medication needs to be a joint decision, as far as possible. It is important to review the impact of the medication and to weigh up the pros and cons. Of course, not all medication is prescribed – ‘natural remedies’ purchased over the counter also carry risks, and there is limited evidence to support their effectiveness.

6 Trauma-informed schools

The UK government’s green paper ‘Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision’ states that:

There is evidence that appropriately-trained and supported staff such as teachers, school nurses, counsellors, and teaching assistants can achieve results comparable to those achieved by trained therapists in delivering a number of interventions addressing mild to moderate mental health problems (such as anxiety, conduct disorder, substance use disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder).

Therefore, a growing body of training for staff is now becoming available to help develop more effective strategies for dealing with various mental health issues in children and young people. Staff are also being encouraged to become more vigilant (on the alert) and proactive (prepared to act) in response to potential triggers and stresses that might lead to mental health problems.

You have already examined many of the issues that affect children’s mental wellbeing throughout the course so far. Can you recall some of these?

You may have thought of the following:

- bullying

- loss, including the death of significant carers, siblings, friends

- parental separation

- physical, emotional and sexual abuse

- neglect

- personal and family illness or disability

- frequent house moves

- living in poverty

- lack of financial stability and resources at home.

Trauma-informed practice means that everybody within an organisation such as a school – from administrators to governors, teachers and parents – can understand, recognise and respond to the effects of all types of trauma.

You might like to look at the following website to see the kind of training that might be involved, and how such training relates back to many of the issues around supporting children’s mental health and wellbeing that have been addressed in this course to date:

Trauma informed schools (make sure to open the link in a new tab/window)

Activity 4 Trauma-informed practice

Watch the two clips of Christine describing her personal journey from teaching in school to counselling children.

As you watch the clips, reflect on what Christine found difficult about the school system, and how perhaps with more effective training in trauma-informed practice as discussed previously in this session, the situations Christine described might be better supported.

Transcript: Video 10

Transcript: Video 11

7 Parenting programmes

You may have heard the comment that, unlike items such as a washing machine, babies do not arrive with an instruction manual. Professional support for parenthood is part of the antenatal care available to pregnant women, and included in antenatal care are practices that are aimed at maximising the chances of strong attachment bonds forming between the baby and parent(s).

Every child born in the UK has a health visitor assigned to them. Part of the health visitor role is to provide support and guidance to parents about their children’s health and development. Session 6 included some information about the role of the health visitor.

Despite the professional support that is available, a shortage of services in some areas and other factors can mean that some parents find parenting a challenge and would benefit from further support. An area of challenge for many parents is their children’s behaviour. Many parents struggle when their children’s behaviour is deemed to be unacceptable both by themselves and others. Support for such parents is available via parenting programmes. However, the reduction in the number of children’s centres has affected the availability of such parenting courses in many areas. Furthermore, professionals need to be careful that deficit models of parenting are not the focus of support programmes and workshops. Deficit models can make parents feel inadequate and undermine perceptions of the family as a whole system with varying strengths, weaknesses and levels of resilience.

7.1 Evaluating parenting programmes

Burton et al. (2014) summarise the key objectives of parenting programmes, which are to:

- promote positive parenting

- improve parent–child relationships

- help parents to manage their children’s behaviour

- reduce the need for discipline and increase the use of positive strategies.

There are several parenting programmes which have been evaluated positively and are evidence-based, such as ‘The Incredible Years’. Programmes such as this one have proven to show significant improvements in children’s behaviour and these ‘parent management training’ interventions are the treatment of choice for children with conduct disorder. A Public Health England (2014) publication includes more information about parenting programmes. There are features of parenting programmes that are essential for the programme to be effective and have a positive impact on the child and family:

- group based: giving parents the opportunity to discuss and learn from each other.

- strengths based: all parents have strengths, and these should be identified and built upon.

- use of a manual: parenting programmes should have a manual that is referred to and used in the classes.

- homework: parents should have tasks to carry out at home to reinforce messages from the parenting classes.

- role play: opportunities to practise skills.

8 Personal reflection

At the end of each session, you should take some time to reflect on the learning you have just completed and how it has helped you to understand more about children’s mental health. The following questions may help your reflection process each time.

Activity 5 Session 7 reflection

- What did you find helpful about this session’s learning and why?

- What did you find less helpful and why?

- What are the three main learning points from the session?

- What further reading or research might you like to do before the next session?

9 This session’s quiz

Well done – you have reached the end of Session 7. You can now check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window and come back here when you have finished.

10 Summary of Session 7

In this session, you have focused on various interventions that can be useful when trained specialists work with individual children and their parents in helping to improve children’s mental health and wellbeing. You have also seen how prescribed medication can sometimes be administered but needs to be undertaken very carefully according to clinical guidelines, such as those developed by NICE. There is also a growing acceptance that children’s wellbeing needs to be the responsibility of everyone who works or is involved with children in a variety of settings, and at different levels within an organisation.

You should now be able to:

- recognise how the power imbalances between child and adult can affect the therapeutic processes

- understand what is meant by cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

- appreciate the role of play and creativity in counselling and therapy with young children

- realise some of the challenges associated with prescribing medication to treat a child’s mental health condition

- understand how parents might be helped to manage children’s behaviour and support their wellbeing.

In the next session, which is the final session of the course, you will be examining the effects of technology on children’s mental health. You will also review the key messages you have hopefully gathered from all of the sessions in this course.

You can now go to Session 8.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Jackie Musgrave and Liz Middleton. It was first published in October 2020.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

Figure 1: Africa Studio; Shutterstock.com

Figure 2: mrfiza; Shutterstock.com

Figure 4: Jantanee Runpranomkorn; Shutterstock.com

Figure 5: courtesy of David Goss, https://www.davidgross.org/

Figure 6: GOLFX; Shutterstock.com

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – The Open University.