Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 21 November 2025, 8:33 AM

Session 8: The influence of screen time on young children’s mental health and wellbeing

Introduction

Much has been written about the impact of screen time and the internet on very young children. As the course draws to a close, you’ll start the final session by looking at the influence of screen time and the internet on young children’s lives, and consider the potential physical and mental health effects. You’ll start to explore some of the ways that we can support children to develop healthy habits in relation to the use of electronic devices and access to the internet and, for older children and adolescents, social media. You’ll also review the systems around children and look at the responsibilities of all who work and care for young children, not just in relation to managing their access to screen time, but also to supporting children’s mental health in broader terms.

Now listen to the audio introduction to this session.

Transcript: Audio 1

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- explain why it is important to support young children to develop healthy approaches to screen time

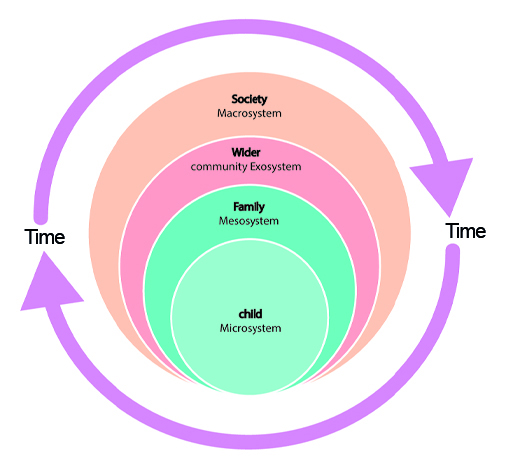

- summarise the ways that the systems around children can support their mental health and wellbeing

- identify your role in supporting young children’s health and wellbeing.

1 Screen time and internet use in the early years

Screen time can be defined as the time spent using a device such as an electronic tablet, computer or games console, as well as time spent watching television. Children increasingly have access to the internet via mobile devices, and many older children also access social media via the accounts of other people known to them. This course is focused on children aged 0–8 years; however, Glazzard and Mitchell (2018) have previously estimated that as many as ‘one in four of 8 to 11 year olds have a social media profile’ (p. 7). This suggests that children become interested in social media and are accessing and engaging with the internet before the age of 8. Therefore, it is important to start educating children from a young age to prepare them to be able to develop healthy ways of using the internet and, when older, social media.

In relation to children aged 0–8 years, it is reported that very young children are being exposed to screen time because they are using electronic devices. This relatively new phenomenon of babies and toddlers using electronic devices is causing alarm because of the concerns that screen time is affecting young children’s health. In response to such concerns, the World Health Organization (WHO) (2019) issued guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age. The guidelines state that babies under one should not have any screen time and children aged 3–4 should be limited to one hour per day.

However, the WHO guidance has not been endorsed by the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, and there is lack of clear guidance for parents and professionals about how much screen time children under 5 should be allowed. This may be seen as unhelpful to parents and professionals who are responsible for educating and bringing up children in a digital world. However, it stands to reason that if children become interested in and, in some cases even potentially dependent on, the use of electronic devices from a very young age, then they are less likely to be engaging with physical activity, which can therefore lead to a higher level of sedentary behaviour. It is suggested that higher levels of sedentary behaviour are associated with childhood obesity (Public Health England, 2019). It is also likely that engaging with screen time from a very young age will ‘fuel’ children’s interest in the internet and also social media as they grow older

As stated previously, many children are thought to be using social media from the age of 8, even when a young person has to be at least 13 years old before they can have an account for TikTok, Facebook and Instagram. Therefore, social media is featuring in the lives of many young people – for better or for worse – and this in turn may have an impact on their mental health. The influences of social media are suspected of being mostly negative, so this session aims to outline some of the concerns about social media and the risks it can pose to children’s mental health, as well as outlining some of the possible positive influences.

Look at the statistics in the infographic in Figure 2. It’s a snapshot of children’s digital lives (Ofcom, 2017).

1.1 The risks of social media for children

The effects of social media on older children’s mental health is of concern, which has been borne out by research by Viner et al. (2019).

Activity 1 Identifying the risks of social media for young children

Make a list of the ways that you think social media, and the internet more generally, can be unhelpful in relation to children’s mental health and wellbeing.

Discussion

The possible impacts of social media and the internet on children’s mental health might include:

- The effect of being exposed to cyberbullying or receiving inappropriate unsolicited messages from adults who are strangers.

- Being able to access problematic websites that promote self-harm and eating disorders. Seeing such information can normalise behaviours for children when they are particularly impressionable.

- An increased risk of developing poor body image because the constant use online of ‘beautiful’ bodies is thought to be linked to lower body esteem and body surveillance (Frith, 2017).

- A greater risk of being exposed to pornographic material and content that promotes violence and intolerance.

- Addiction: children who spend a great deal of time on social media, and the internet more generally, run the risk of becoming addicted to its use. Hoffmann et al. have gone as far as to assert that ‘social media is more addictive than cigarettes and alcohol’ (cited in All Party Parliamentary Group, 2018, p. 66). But it is worth remembering that something can be highly addictive (like caffeine) and not have major negative consequences in the same way as alcohol and other drugs.

As well as affecting young children’s mental health, social media can impact on physical health because:

- The lack of sleep that children and young people experience when using the internet and social media late into the night can lead to tiredness, irritability and a general lack of energy.

- Engaging with the internet and social media can mean that there is less time for taking exercise, so children are being deprived of the positive effects on wellbeing that are associated with exercise.

Viner et al.’s (2019) findings, which were published in The Lancet: Child & Adolescent Health journal, were taken from a study carried out involving 866 children aged 13–16 in England. They concluded that children who ‘frequently use social media’ (defined as ‘used multiple times daily’) are significantly more likely to experience mental health problems, and that the situation is probably worse for girls than it is for boys. The researchers suggested that exposure to cyberbullying or displacement of sleep or physical activity as a result of very frequent social media use could explain the increased risk. The findings from Viner et al.’s study highlight the importance of ensuring that early work occurs to help avoid the negative impact of social media on children’s mental health. Such interventions should include measures to increase resilience to cyberbullying, as well as ensuring children receive adequate sleep and physical activity. You will return to these points later in this session.

Although the negative effects of screen time, including social media use, are discussed extensively, it is important to consider the benefits of screen time, the internet and social media for older children. You will look at this briefly in the next section.

1.2 The benefits of the internet and social media for children

Using the internet can open channels of communication that were previously unavailable to people. For those who live in remote areas of the world, who have a disability, are from a minority group (for instance intersex children who are born with Variations of Sex Characteristics) or have other restrictions on how they access information, the internet is a rich and important resource. It gives access to information that is beneficial and useful, and it also allows them to connect with others like themselves so that they can develop knowledge and understanding of the world around them.

Young children have been born into a world where the internet is a taken-for-granted resource. However, the internet has only been around for the last 25 years or so and for many adults, it is still a source of wonder. Because it is relatively new, and because the ways that we can use the internet are continuously evolving, it can be tricky to know how to teach and guide children about its use. Clearly, the digital world is not going away, so it is important to identify ways that we can work together to support children and teach them how to harness the positive effects of living with screens and accessing the digital world.

1.3 Working together to manage children’s screen time

Concerns about the impact of the internet and social media on young children’s mental health are common in countries where children and young people can easily access electronic devices, the internet and social media. Society has a shared responsibility to guide children to develop healthy ways of using electronic devices and accessing the internet, ensuring that screen time does not become ‘digital babysitting’ and overused. You’ll now look at this responsibility from the different perspectives of all involved.

Governments around the world: In England, there is work in progress to produce an internet safety strategy (Her Majesty's Government, 2018), which will set out more detailed measures to address harmful and illegal online content. This will include proposals on a social media code of practice and online advertising.

Health service guidance: There is a need for screen time to be a public health issue and responded to in a similar way that other activities that potentially damage health are approached. The Chief Medical Officer (2019) has published a commentary on the use of children’s screen time, as has the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2018).

Pre-schools and schools: All policies need to include health promotion messages relating to managing screen time, promoting physical health and ensuring pre-school children get adequate sleep.

Parents and families: Of course, parental and caregiver supervision of screen time usage is very important, but in addition to this, the previously mentioned Chief Medical Officer’s commentary (CMO) (2019) suggests that parents need to examine their own behaviour in relation to how much time they spend on screens. The CMO includes the following discussion questions, produced by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, to help families make decisions about their screen use:

- Is your family’s screen time under control?

- Does screen use interfere with what your family want to do?

- Does screen use interfere with sleep?

Activity 2 How can you manage children’s screen time?

The following points are taken from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) report (2018), which includes guidance taken from the American Academy of Paediatrics (2016). Consider whether these points are relevant to the children you work with or care for. (For children younger than 18 months, avoid use of screen media other than video chatting.)

- Parents of children 18 to 24 months of age who want to introduce digital media should choose high-quality programming and watch it with their children to help them understand what they're seeing.

- For children age 2 to 5 years, limit screen use to 1 hour per day of high-quality programs. Parents should co-view media with children to help them understand what they are seeing and apply it to the world around them.

- For children age 6 and older, place consistent limits on the time spent using media, and the types of media, and make sure media does not take the place of adequate sleep, physical activity and other behaviours essential to health.

- Designate media-free times together, such as dinner or driving, as well as media-free locations at home, such as bedrooms.

Discussion

Were you surprised by any of the above points? Have you identified a point that you feel needs to be addressed in relation to the children you work with or care for? Do you think there are difficulties or barriers to working with this guidance?

You may think that managing children’s screen habits needs to start very early in childhood; if so, you are absolutely correct. In the same way that children need to be supported in learning about their behaviour in all aspects of life, they need to be taught about safe and healthy ways of using the internet and social media. Children need support to develop their digital habits so they reflect respect for others. In this way, the negative impact of using the internet and social media can be reduced.

Clearly, there is a need for an international agreement about consistent and robust guidance relating to safe levels of screen use for children. In addition, more reliable research and support needs to be available for parents to help them understand the importance of developing healthy habits in relation to screen time.

From a one-day event on research, policy and communication in a digital age, Jon Sutton (2018) reports on the need for better research on the whole topic of screen time use by children to better inform parents.

What do parents want from us as psychologists? Tamsin Greenough Graham represented the Parenting Science Gang, 2000 parents united by a desire to have scientific evidence to drive parenting. She said that a common fear among parents is the judgement of other parents and healthcare professionals, many of whom ask: ‘how long does your child spend in front of screens each day?’ In determining whether it’s a problem, Greenough Graham said: ‘We don’t know those answers. The information has not been made available to us, at least in a way we can use it.’ But she also reported that parents want to know the benefits of screen time, and what screen time life skills we need to teach our children: ‘If our children were off playing with LEGO during that time, none of us would feel guilty. We value LEGO. What is there to value about screen time? Tell us.’

To read more about this subject, see the links in the ‘Further reading’ section at the end of the session.

On a final, more optimistic note, you may now be aware that there is a great deal of work that can be done to educate very young children about the impact of inappropriate use of social media. As you have seen, the use of electronic devices (like gaming) has been found to be addictive, while at the same time having positive benefits. So, it is important that good habits are developed in very early childhood. Parents also need to be supported to help them implement restrictions as well as optimise the use of technology so that children are better prepared to engage more positively within various digital environments.

In this section, you’ve seen that supporting children to develop good screen time habits is important in order to lay the foundations for the use of the internet and social media in later childhood.

You’ve also seen that managing children’s access to social media cannot be solely a responsibility for government. There is an urgent need for adults – especially parents and professionals who work with children – to devise approaches to manage and limit children’s access to social media. In addition, there is a great deal of work that can be done to educate very young children to learn about the impact of inappropriate use of social media, and help them increase more positive engagement with new technologies they encounter in the current digital age.

In the next section, you will review the content of previous sessions and summarise the key points. These key points will be useful as you complete the final quiz at the end of the session to earn your badge.

2 Reviewing the way that the systems around the child support mental health

In the final part of the course, you will review some of the main points from the previous sessions.

As you saw in Session 1, over time some children have always been affected by mental ill-health, but it has only recently been recognised as such.

In the following sections, you will review some of the content of the previous sessions and summarise the roles and responsibilities of individuals within each of the systems in promoting good mental health in children.

2.1 Within the child

It is crucial to view mental health concerns at an individual level, since not all children react or respond in a similar way. It is also important to look beyond the often generalised and negative issues raised by concerns such as the impact of the internet and social media on children’s mental health. However, the presence of some factors in the immediate system around the child are clearly beneficial to promoting good wellbeing and good mental health.

Play is an integral aspect of the everyday life of very young children. As you’ve seen, giving children opportunities to engage with play in different contexts is vital. Ensuring that children have access to outdoor play and activities is also highly beneficial in promoting wellbeing.

You have considered the importance of giving children opportunities to develop resilience so they can thrive and develop self-esteem and confidence. Children can develop resilience in the face of adversity, especially if they have support from their family and professionals, such as teachers.

2.2 Within the family and parents

Parents need to be able to access good antenatal care and to receive appropriate support with parenting. Parenting support can help to promote children’s wellbeing and make a positive contribution to their mental health; this can prevent problems from developing.

As you saw earlier this session, excessive screen time is appearing to have some negative effects on young children, so parents need to be supported to introduce safe ways for their children to engage with the digital world.

2.3 Within the wider community

The wider community includes the local neighbourhood and services. For example, children’s centres provide parenting classes, play services and early education and they make a positive contribution to supporting children’s mental health and wellbeing. However, many children’s centres have closed since 2010, leaving a gap in the services available in the wider community.

Local neighbourhoods: safe outdoor areas with well-maintained parks and playgrounds can make a positive contribution to children’s wellbeing. Being outdoors and engaging with others can also help to reduce children’s screen time (All Party Parliamentary Group, 2019).

Professionals delivering children’s services: there is a need to promote knowledge about children’s mental health as well as greater understanding of the ways that children’s wellbeing can be improved. In relation to very young children, educators in pre-school and school settings can make a positive contribution to supporting children’s mental health and wellbeing. Early childhood and primary curricula have many strategies that can make a positive contribution. High-quality early education is especially important; for instance, the key person helps young children to develop a relationship with practitioners who know the children’s needs and, in negotiation with parents, can help identify how best to meet such needs. High-quality early education and care requires adults to listen to how children express themselves, both verbally and non-verbally, so that the children’s voices can be taken into account in all decision-making affecting their lives.

2.4 The role of society

Of course, each individual child and adult is a member of society. Therefore, it can be argued that everyone has a responsibility to support children’s mental health and wellbeing.

There are many ways that such support can be demonstrated, for example:

- Increased understanding of the critical 0–2-year period of life and how good foundations for the future are laid down when parents and young children have loving relationships and strong attachments. In line with this suggestion, there needs to be funding for high-quality early education for children.

- Adopting the messages in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, listening to children and taking their views into account.

- Creating safe environments for children to be able to explore and enjoy both indoor and outdoor play activities.

- Changing attitudes towards children so that there is increased tolerance for children.

There is a pressing need for government to support the creation of a curriculum that is not only suitable for children’s age and stage of development, but one that can increase children’s autonomy as well as enhance their creativity and wellbeing.

The Department of Health and Department for Education’s green paper ‘Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision’ (2018) is a significant contribution to reacting to the number of children being diagnosed with mental health conditions. The green paper promotes an integrated and holistic approach to addressing the problem. One proposal is for schools to have a designated senior lead for mental health in schools by 2025. There will be a need for high-quality training to equip staff to be able to identify children with mental health problems and know how to support them in schools.

3 The future

As parents and/or professionals working and caring for children, increasing our knowledge of how to prevent some of the issues that can contribute to poor mental health and mental illness is a positive step to take. It is important to keep in mind the ‘recipe’ for emotional wellbeing and the holistic nature of children’s health and wellbeing. While funding for children’s services to improve wellbeing and mental health is important, as well as having high-quality professionals, it needs to be kept in mind that many of the ingredients in the recipe relate to how well we develop relationships with children, and we can all do more to develop and maintain those relationships.

The final section includes some useful resources for anyone with an interest in children’s health and wellbeing.

4 Resources for parents and professionals

This section includes some resources that are available for parents and professionals:

Action for Children: Children’s mental health

Barnardos: Adverse Childhood Experiences

Public Health England: The mental health of children and young people in England

Time to Change: Mental health resources for schools and parents

5 Personal reflection

At the end of each session, you should take some time to reflect on the learning you have just completed and how it has helped you to understand more about children’s mental health. The following questions may help your reflection process each time.

Activity 3 Session 8 reflection

- What did you find helpful about this session’s learning and why?

- What did you find less helpful and why?

- What are the three main learning points from the session?

- What further reading or research might you like to do now that you’ve finished this course?

6 This session’s quiz

It’s now time to complete the Session 8 badged quiz. It is similar to the previous quizzes but this time, instead of answering 5 questions there will be 15, covering Sessions 5–8.

Session 8 compulsory badge quiz

Remember that the quiz counts towards your badge. If you’re not successful the first time, you can attempt the quiz again.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window by holding down Ctrl (or Cmd on a Mac) when you click the link. Come back here when you are done.

7 Summary of Session 8

Children’s mental health is a cause for global concern. It is thought in England alone that 10% of children aged 5–16 have a diagnosable mental health disorder that will require professional support. However, many causes that can lead to compromised mental health in children can start at conception, and it is important not to overlook the importance of the 0–2 year age group. Therefore, we need to increase awareness of how good mental health can be promoted in early childhood.

It is important that adults – both parents and professionals – are equipped to understand, identify and become more knowledgeable about the prevention and causes of children’s mental health. Increasing knowledge and understanding of the role of adults in supporting children’s mental health is vital to reverse the trend of increasing numbers of children who are being diagnosed with a mental health condition.

You should now be able to:

- explain why it is important to support young children to develop healthy approaches to screen time

- summarise the ways that the systems around children can support their mental health and wellbeing

- identify your role in supporting young children’s health and wellbeing.

Where next?

You might be particularly interested in the course, Introduction to adolescent mental health, which can also be found on the Universal level courses page of the North Lanarkshire Council Skills Pathway portal.

New to University study? You may be interested in our courses on Education or Early Years.

Making the decision to study can be a big step and The Open University has over 40 years of experience supporting its students through their chosen learning paths. You can find out more about studying with us by visiting our online prospectus.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Jackie Musgrave and Liz Middleton. It was first published in October 2020.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Images

Figure 1: chameleonseye; Getty Images

Figure 2: Children and Parents: Media Use and Attitudes Report 29 November 2017 ; (c) Ofcom

Figure 3: Syda Productions; Shutterstock.com

Figure 4: karelnoppe; Shutterstock.com

Figure 5: Patryk Kosmider; Shutterstock.com

Figure 7: Olga Enger; Shutterstock.com

Figure 8: EdBockStock; Shutterstock.com

Figure 9: DenKuvaiev; Getty Images

Figure 10: Rawpixel.com; Shutterstock. com

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – The Open University.