Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 23 February 2026, 9:52 PM

Unit 4: Towards new futures – a role for partnership

Introduction

Welcome to Unit 4 of Sustainable pedagogies.

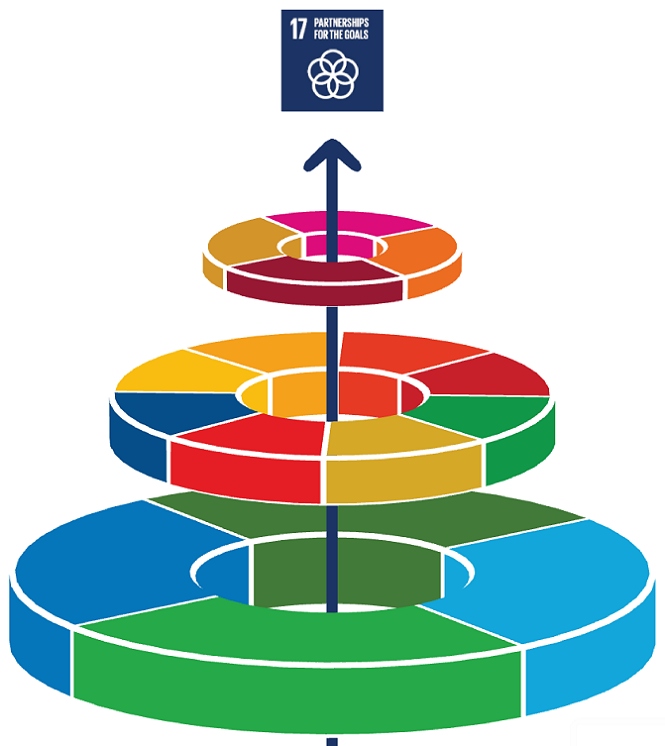

Meeting the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as set out by UNESCO (Figure 1) and ratified by its member countries, becomes more and more urgent as the world suffers an increase in climate-related events such as wildfires and flooding. These events are directly attributable to human activity affecting the climate.

The idea of partnership is part of SDG 17 which is about revitalising global partnerships for sustainable development. The SDG agenda needs to be universal and call for action by all countries – developed and less well-developed – because actions by and within one country can be seen to affect every country. Therefore, meeting all the SDGs requires partnerships between governments, the private sector, and civil society, which is why partnership runs through all other goals.

Figure 2 shows partnership running through the three layers of SDGs and the layer each SDG relates to:

- Biosphere (base) – SDGs 6, 13, 14, 15.

- Society (middle) – SDGs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 11, 16.

- Economy (top) – SDGs 8, 9, 10, 12.

Working with others may seem like an obvious approach to sustainability but it is in considering why and how partnership is so important that the imperative to act that way is understood. Partnership links to other aspects of sustainable pedagogy (transdisciplinarity, compassion, participation) discussed in this course and cuts across many other pedagogies.

In this unit, we will discuss not just how to use partnership as a pedagogy but also how important it can be to exemplify it to learners so that they see and understand its power. This unit outlines what partnership means and why this term is used as opposed to collaboration. It also looks at the tensions that exist in conventional pedagogies and how partnership can address these. The unit ends by giving you a chance to consider what partnership might look like to you.

Remember, to obtain your digital badge, you must have posted a contribution to at least one forum discussion in Units 1–7 and one of the forum discussions in Unit 8. You must also have completed the quiz at the end of Week 5 and scored at least 80%.

The items labelled ‘Explore’, which have the binoculars ![]() icon beside them, are optional and are offered for those who want to explore the ideas being discussed further.

icon beside them, are optional and are offered for those who want to explore the ideas being discussed further.

Next go to Unit 4 learning outcomes.

Unit 4 learning outcomes

By the end of this unit you will have:

- Considered the idea of ‘wicked problems’ that can only be resolved not solved and explored how partnerships and collaboration can help.

- Considered tensions in different types of pedagogy and relation to education for sustainable development (ESD).

- Evaluated pedagogies for partnership in your own setting.

Activity planner

| Activity | Task | Timing (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| 4.1 | Read about wicked problems. Apply the notion of wicked problems and partnership to your own teaching context. Post on forum discussion. | 45 |

| 4.2 | Watch video and write notes about the impact of the methodologies used. Post on forum discussion. | 45 |

| 4.3 | Heart, head and hands Building partnerships from the ground up. Post on forum discussion. | 45 |

1 Why partnership?

Partnership as envisioned in SDG 17 involves working with others towards a common goal. In this case partnership seems a better term to use than collaboration to describe the needful enduring and committed relationships that will enable progress towards sustainability. A partnership can be regarded as a defined relationship, a long-term understanding of the commitment offered and required by all the parties that are involved.

Collaboration can be seen as a less formal commitment. Two institutions, groups or individuals may collaborate on a certain task, each using the skills they have in pursuit of completing that task, informally filling in for the other if support becomes necessary or circumstances alter. Collaborations often are formed for short-term, specific projects without formal obligations. Partnerships, on the other hand, are more structured and typically involve a long-term commitment with shared responsibilities, risks, and benefits. It is in the setting out of those roles, responsibilities, risks and benefits that partnerships are formed. So, in this unit partnerships formed for learning will be discussed, with their defined roles and responsibilities rather than collaborative learning. Within effective partnerships the benefits of collaborative learning are likely to be realised as the structure of a partnership will help those benefits to be realised.

In order to use partnership as a pedagogy, learners will need to develop the skills and qualities that support partnership working. Partnership is seen as a sustainable pedagogy through learning to form, structure and work within a partnership, within which learners can grow and develop the collaborative skills that are seen as necessary to live sustainably.

Activity 4.1 Wicked problems

1. ![]() Read Head (2022) ‘The Rise of “Wicked Problems”—Uncertainty, Complexity and Divergence’, from page 25 ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning’, to the end of page 27, then the table at the top of page 32.

Read Head (2022) ‘The Rise of “Wicked Problems”—Uncertainty, Complexity and Divergence’, from page 25 ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning’, to the end of page 27, then the table at the top of page 32.

These extracts have been included to help you understand more about wicked problems.

2 Partnership as a pedagogy

Many current pedagogies used in schools and in Higher Education settings are inherently individualistic, but the evidence review by the Educational Endowment Foundation (EEF) in 2021 showed there are clear benefits in using collaborative pedagogies, including partnership ways of working, in terms of improved learning. Such a view is antagonistic to the current neoliberal society but is considered a necessity by UNESCO if society is to move towards living sustainably. Neoliberalism (Venugopal, 2015) refers to the current political, economic and social arrangements within society that emphasise market relations, re-tasking the role of the state and individualism.

Partnership as a pedagogy is an important focus in learning and education as it allows individuals to learn about ways of working which will benefit them and progress their learning. Partnership echoes Littleton and Mercer’s (2013) book on ‘interthinking’ as a way to enhance learning, in that each partnership must move towards meeting agreed goals together, including listening to and respecting the views of each member of the partnership. Importantly in partnership, as in interthinking, the shared responsibilities, risks, and benefits are set out at the beginning of the cooperative task. Working in partnership whilst in formal education will build the learners’ skills and understanding that learning and knowledge can be used for the betterment of not just themselves, but of society and the world.

Partnership pedagogies in formal education are vital because:

Young people will require a level of democracy, citizenship and altruism that is lacking in our current education system and is often antagonistic to the dominant neoliberal values, structures and underlying assumptions of our increasingly globalized education systems.

2.1 Partnerships to act and transform

As explained earlier, although partnership involves collaboration, it involves more structure and better-defined roles and responsibilities. Collaboration is a skill, which may come naturally to some, but which others need to be helped to learn. It is a vital part of partnerships hence part of using partnerships as a pedagogy will be facilitating ways for learners to understand the power of collaborative working.

As partnership is defined as a structure to meet goals, it offers a frame for building an understanding of concepts important to resolving an issue, but it also offers access to multiple different views of what constitutes resolution, which often results in a shifting of views. This way of working also allows learners to see and appreciate how ideas and realities are connected worldwide. Such ways of working are vital in living sustainably where compassion and change are required along with building an understanding of someone’s place and power in the world, and their effect on others and the environment.

Partnership working is seen by UNESCO (2023) as a transformative aspect of education for sustainable development (ESD) as the partnerships act as a bridge between learning and action and facilitate a ‘shift—from learning how to understand to learning how to act and transform’ (Schnitzler, 2019, p. 243).

Reflection

Reflection

Think of partnerships that you know about.

Why do we form partnerships?

![]() Write down three (or more) reasons why you would partner with someone else. Think of partnerships from both an educator’s point of view and from the learner’s point of view.

Write down three (or more) reasons why you would partner with someone else. Think of partnerships from both an educator’s point of view and from the learner’s point of view.

What could be the purpose of a possible partnership(s)?

In the case of the existing partnerships you have identified, how are the roles and responsibilities set out? In the case of the newly imagined partnership(s), how would roles and responsibilities be set up optimally?

3 Layers of partnership

Partnership can be seen as being formed in layers. Partnership between individuals, groups of individuals or organisations initially requires a clear purpose and structure. The first layer is the initial partnering, which will include decisions about the purpose, the structure and the roles and responsibilities each element of the partnership will take on. As the partnership becomes more established deeper layers are created in the form of the relationships which will uphold and sustain that partnership. These layers create opportunities for learning within that partnership to be stimulated.

A key part of partnership as a pedagogy is creating learning spaces where learning in the partnership can take place. To be successful as a pedagogy, the purpose of the partnership must allow for a move from simply learning as individuals to putting that learning into action. The more the purpose of the partnership is to tackle complex problems or difficult issues (i.e. wicked problems) the more learners will be involved in pedagogies that develop their skills to work sustainably, allowing them to learn the skills, understanding and compassion that are vital for living and learning sustainably.

UNESCO (2023) sees global partnerships as a vital part of SDG 4 (Quality Education) and EDS. Therefore, creating learning spaces and communities that allow for external as well as internal partnering will be important in helping learners understand themselves as global citizens (Bennell, 2015). There can be much to consider in these networks and educators often describe partnership work as challenging. Where internal collaboration and networking are frequent, such that the knowledge, skills, and understanding of key players are shared, commitment to ESD can grow. In Audio 1 below, Sheila Bennell outlines what can work well, particularly in busy school environments, to build a global citizenship approach in partnership with both internal and external colleagues.

Transcript: Audio 1 Sheila Bennell on partnership and a global citizenship approach

3.1 Brave spaces and critical dialogue

The use of a language of appreciation and cooperation is part of the necessary communication and dialogue which is a crucial part of partnership work. Partnership working requires that all those in that partnership engage in critical dialogue. The benefits of collaborative learning spaces which are set up through partnerships can be seen as ‘brave spaces’ (Arao and Clemens, 2013) in which experiences and knowledge can be shared and the formation of action through dialogue can be experienced and learned. The creation of ‘brave spaces’ acknowledges that it is often impossible to remove risk and ‘implies that there is indeed likely be danger or harm – threats that require bravery on the part of those who enter. But those who enter the space have the courage to face that danger and to take risks because they know they will be taken care of’ (Cook-Sather and Workworth, 2016, p. 1). The four stages of critical dialogue which are needed to build this courage are set out in Table 1 below.

Table 1 The four stages of critical dialogue (Wood, 2017)

| Problematisation | Being able to see what we accept as ‘normal’ through different eyes and so challenge assumptions. |

|---|---|

| Conscientisation | Becoming conscious of our situation and organising to resist it. |

| Humanisation | Building solidarity as peers stop regarding those regarded as oppressed as an abstract category and start to see them as persons who have been dealt with unjustly and have been deprived of their voice’ (Freire, 1970). |

| Praxis | Acquisition of critical awareness by oppressed people of their own condition, and, in solidarity with one another, begin to ‘struggle for liberation’ (Freire, 1970). |

These stages of critical dialogue can be exemplified in the ‘Youth Solidarity Dialogue Model’ (Wood, 2017) which was set up as the mode of partnership between marginalised young people in Malawi and young people in Scotland. This model explores the nature of equality versus equity in partnerships. Thinking about power and context within partnerships is important if learners are to understand social justice and global citizenship. Critical dialogue takes the partnership beyond simple to something more complex which has the power to change and develop the attributes required for living sustainably.

Explore

Explore

Learn more about the power of partnering across the globe and using critical dialogue as a way to engender learning within the Scotland–Malawi Partnership.

Access and read the STEKA skills report.

Activity 4.2 Learning from partnerships

![]() Watch Video 1 below of Emma Wood talking about partnerships.

Watch Video 1 below of Emma Wood talking about partnerships.

Video 1 Emma Wood on partnerships (around 8 minutes)

Consider the purpose of the partnerships that were created and make notes in your learning journal about your responses to the following questions:

2a. What are the key impacts of the project on the young people involved, both in Scotland and in Malawi?

3. ![]() What do you feel the young people involved learned from it and how might it be termed an example of a sustainable pedagogy?

What do you feel the young people involved learned from it and how might it be termed an example of a sustainable pedagogy?

Post around 200 words on the Activity 4.2 forum discussion summarising your reactions to this partnership.

Explore

Explore

Read the short editorial of an issue of Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education which provides an overview of five reflections by three undergraduate students and two academic members of staff who participated in a Students as Learners and Teachers (SaLT) program at Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges.

Cook-Sather, A. (2016) ‘Creating Brave Spaces within and through Student-Faculty Pedagogical Partnerships’ (brynmawr.edu), Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education. Available at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1143&context=tlthe (Accessed 27 October 2023).

4 Learning to partner while partnering – performing and exemplifying partnerships

It is important not to see partnership as always warm and cosy. Just a short reflection will identify partnerships that have not succeeded or that have taken a great deal of work to establish and/or to keep going. Häggström and Schmidt (2022) suggest that partnerships will only succeed where the complexity, sharp edges, fuzziness and contradictions which constitute a shared situation are embraced. Just as Freeth and Caniglia (2020) showed that sustainability researchers learned best to collaborate while collaborating, learners will only learn the skills and understandings that are necessary to be an effective partner in a collaborative learning partnership. Collaborations can be spaces that comprise epistemic, social, symbolic, spatial, and temporal dimensions and that produce different degrees of comfort and discomfort in those that participate in them.

In creating the conditions necessary for learning to take place within a partnership, learners will also need to pay attention to the feeling of discomfort and risk which are experienced in any space where learning takes place. When learners are developing their understanding of how partnerships work, how to be a partner and how to learn within that partnership they will, of necessity, make mistakes, feel they could have done better and experience failures in some way. Sometimes the partnership itself will be at risk of failure because of lack of commitment, ineffective structuring of the partnership or because an important part of the partnership is unable to fulfil their commitments for some good reason. Therefore, recognition of the risks that learners take in entering that learning space is necessary, as is support to overcome any negative or uncomfortable feelings and when learning from the discomfort of making mistakes.

4.1 Heart, head and hands

There are three ways that engaging in partnerships or collaborations can strengthen learners’ capacities to continue to work collaboratively and build partnerships:

Ways of working

| 1. Ways of being (heart) – Learners can be encouraged to develop ways of being in collaborative or partnership learning situations that increase tolerance for discomfort in the face of challenges and openness so that they can gain new collaborative knowledge and skills. | |

| 2. Ways of knowing (head) – Encouraging reflection on the partnership, its effectiveness and impact can develop insight, understanding and awareness that support further collaboration and partnerships. | |

| 3. Ways of acting (hands) – Partnerships that have a practical and measurable purpose within their communities locally and globally, advance collaboration skills interpersonally, practically and technically. |

Activity 4.3 Heart, head and hands

1a. ![]() Consider a partnership that you might develop (local or global) that might help your learners develop the skills they need to act sustainably in the world. This can be:

Consider a partnership that you might develop (local or global) that might help your learners develop the skills they need to act sustainably in the world. This can be:

- Realistic – one you could add into your learners’ scheme of work fairly soon

- Aspirational – one you think would really open your learners’ eyes to the value of partnership but that you currently cannot see how to make work in your learning context.

1b. ![]() Now think in terms of ‘heart, head and hands’:

Now think in terms of ‘heart, head and hands’:

- i.First, refer to the table in your learning journal then outline your idea for partnership as a pedagogy in your learning context.

- ii.Now draw three columns – one for each way of thinking about partnership learning. Think quite practically for each column – the idea is to think about how these skills can be built into a partnership from the ground up?

See the example questions in Table 2 below and use the boxes in the row below to record your thoughts.

Table 2 Partnership learning and ‘heart, head and hands’

| Partnership learning | ||

|---|---|---|

| How will the partnership work? Who will be in the partnership? Will it be local, in the wider community or global? What will be the purpose of the partnership – what is it intended to achieve? What will be the roles and responsibilities within your partnership? What impact do you see the partnership having? | ||

| Heart | Head | Hands |

| Ways of being – how will learners be encouraged to increase their tolerance for discomfort in the face of challenges and be open- minded so that they can gain new knowledge and skills? | Ways of knowing – how will learners reflect on the effectiveness and impact of this partnership in order to develop insight, understanding and awareness? | Ways of acting – how will learners consider the practical and measurable purposes of the partnership within local and global communities, and therefore develop interpersonal, practical and technical skills and understanding? |

2a. How have you been considering building in these capacities (heart, head and hands) from the ground up in this partnership? You may have thought about this in terms of participation, as has been explored in the previous unit by the inclusion of your learners at every step of the process in building and maintaining a partnership.

2b. ![]() Participation pedagogies go hand in hand with partnership, and particularly in terms of ideas of equity and equality as has already been seen.

Participation pedagogies go hand in hand with partnership, and particularly in terms of ideas of equity and equality as has already been seen.

Summarise your ideas for partnership, paying particular attention to what you consider your learners may learn from engaging within this partnership and post around 100 words on the Activity 4.3 forum discussion.

5 Summary of Unit 4

Partnership is considered within the Sustainable Development Goals set out by UNESCO as key to reaching all seventeen of the SDGs. The skills, understanding and learning that can be achieved through partnership locally and globally are regarded as fundamental to achieving a sustainable way for all to live in this world. Collaboration as a competency is essential in forming effective partnerships but partnership also requires commitment that is longer term than many of the ways collaborative skills are used.

When used as a pedagogy, partnership can move learners understanding from an individualistic view to a more compassionate and empathetic collective view as part of communities and wider society and can help learners understand their role and responsibility for the world around us, both human and non-human.

Effective communication is essential in creating effective partnerships. Creating learning spaces where critical dialogue can be learned and used can create brave spaces that can allow learners to both learn about issues in their immediate environment and globally, and to deliberate and learn about what must be done in terms of putting the learning into action. These need to be supported spaces to recognise the courage needed to deal with tensions and discomfort in challenging norms and assumptions, and recognising vulnerabilities due to power imbalances. Where learners recognise and address imbalances within a partnership this allows the partnership to engender more skills to be learned that will allow learners to engage in sustainable reasoning and action.

Finally, learners can only understand and learn all the skills that are needed to be an effective partner while acting in a partnership. To develop collaborative capacities, learners need to consider their ways of being, knowing and acting and to become comfortable with discomfort as that will allow them to see transformation through learning.

Unit 4 cards

Click/tap each card to reveal the text.

Continue to Unit 5: Transdisciplinarity.

Further reading

Cook-Sather, A., and Woodworth, M.K. (2016) ‘Creating brave spaces within and through student-faculty pedagogical partnerships’, Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education, 1(18), p.1. Available at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/ cgi/ viewcontent.cgi?article=1143&context=tlthe (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Wood, E. (2017) ‘An Alternative to Voluntourism’, Steka skills and Queen Margaret University. Available at: https://www.stekaskills.com/ our-model-of-critical-dialogue-for- (Accessed: 14 February 2024).

References

Arao, B., and Clemens, K. (2013) ‘From safe spaces to brave spaces: A new way to frame dialogue around diversity and social justice’, in L. M. Landreman (Ed.), The art of effective facilitation, pp. 135–150. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Bennell, S. (2015) ‘Education for sustainable development and global citizenship: Leadership, collaboration, and networking in primary schools’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 7(1), pp. 5–32. Available at: https://uclpress.scienceopen.com/ hosted-document?doi=10.18546/ IJDEGL.07.1.02 (Accessed: 5 March 2024).

Carcasson, M. (2016) ‘Tackling Wicked Problems Through Deliberative Engagement’ National Civic Review, 105(1), pp. 44–47. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ ncr.21258 (Accessed: 5 March 2024).

Cook-Sather, A., and Woodworth, M.K. (2016) ‘Creating brave spaces within and through student-faculty pedagogical partnerships’, Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education, 1(18), pp.1. Available at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/ cgi/ viewcontent.cgi?article=1143&context=tlthe (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

EEF (2021) Collaborative learning approaches, Educational Endowment Fund. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/ education-evidence/ teaching-learning-toolkit/ collaborative-learning-approaches (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Freeth, R. and Caniglia, G. (2020) ‘Learning to collaborate while collaborating: advancing interdisciplinary sustainability research’, Sustain Sci, 15, pp. 247–26. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/ s11625-019-00701-z (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Freire, P. (1970) The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum Books.

Häggström, M. and Schmidt C. (2022) Relational and Critical Perspectives on Education for Sustainable Development. New York, NY: Springer.

Head, B.W. (2022) ‘The Rise of “Wicked Problems”—Uncertainty, Complexity and Divergence’, in: Wicked Problems in Public Policy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/ 978-3-030-94580-0_2 (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Littleton, K. and Mercer, N. (2013) Interthinking: Putting talk to work. London: Routledge. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.4324/ 9780203809433 (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Lundström, N., Raisio, H., Vartiainen, P. and Lindell, J. (2016) ‘Wicked games changing the storyline of urban planning’, Landscape and Urban Planning, 154, pp. 20–28. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/ j.landurbplan.2016.01.010 (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Orr, D. (1992) Ecological literacy: Education for a post modern world. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Rittel, H. and Webber, M. (1973) ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning’, Policy Sciences, 4(2), pp. 155–169. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/ stable/ 4531523 (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Schnitzler, T. (2019) ‘The Bridge Between Education for Sustainable Development and Transformative Learning: Towards New Collaborative Learning Spaces’, Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 13(2), pp. 242–253. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1177/ 0973408219873827 (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Schulte, M. (2022) ‘Exploring the Inherent Tensions at the Nexus of Education for Sustainable Development and Neoliberalism’, Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 16(1–2), pp. 80–101. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1177/ 09734082221118621 (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

UNESCO (2023) Renewing the Social Contract for Education. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/ en/ futures-education/ new-social-contract?hub=81942 (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Venugopal, R. (2015) ‘Neoliberalism as Concept’, Economy and Society, 44(2), pp. 165–187. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/ doi/ abs/ 10.1080/ 03085147.2015.1013356 (Accessed: 5 March 2024).

Wood, E. (2017) ‘An Alternative to Voluntourism’, Steka skills and Queen Margaret University. Available at: https://www.stekaskills.com/ our-model-of-critical-dialogue-for- (Accessed: 14 February 2024).