Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 23 February 2026, 9:51 PM

Unit 6: Learning in transition − perspectives and practices

Introduction

Welcome to Unit 6 of Sustainable pedagogies.

At this moment in time, there is globally agreed scientific data on the impacts of human-induced planetary warming. There are also lived experiences of a changing climate and widespread environmental degradation. Our climate is changing but actual societal changes are not keeping pace. What is lacking is a sufficient urgency to respond to the certainty of the consequences of climate change. Indeed, the urgent need for change is ultimately about human survival. Over vast geological timespans the climate has warmed and cooled and extinctions have occurred along the way. Climate change at the rate it is occurring today affects the immediate environment that allows humans to flourish. However, human flourishing has both historically impacted and is presently impacting, the survival of many other species and ecosystems. As the impacts of change become more obviously related to human behaviour, goals and actions to mitigate damage and adapt to change are beginning to emerge.

Empowering learners to develop new understanding, skills and practices is foundational to an effective transition from a society dependent on fossil fuels to one based on renewable energy and regenerative resources. In this sustainable transition, eco-literacy is as critical a literacy as numeracy and traditional literacy have always been. Understanding our place in nature and natural systems is fundamental to developing a society that can care for and protect, the Earth and its diversity.

Goleman et al. (2012) suggest that ecological intelligence is inherently collective and cannot be built in isolation. Rather it is constructed because of a shared understanding and shared actions that support networks of relationships where ecological sensibility can be built. This presents opportunities for existing collectives to create new spaces for learning and practice towards a sustainable transition – whether they be formal learning places in the form of schools or colleges or informal learning environments such as workplaces and communities. Transition demands interventions in existing systems to facilitate change.

Next go to Unit 6 learning outcomes.

Unit 6 learning outcomes

By the end of this unit you will have:

- Understood different perspectives on education for sustainability.

- Explored the characteristics of transformative learning needed to build effective ecological intelligence for sustainable transitions.

- Investigated an eco-literacy activity aimed at different learners.

Activity planner

| Activity | Task | Timing (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| 6.1 | Reflect on how we might successfully enable education for sustainability. Post on forum discussion. | 30 |

| 6.2 | Explore transformative learning experience characteristics and describe and share how you could integrate these approaches into your teaching. Post on forum discussion. | 30 |

| 6.3 | Create an eco-literacy learning activity. Post on forum discussion. | 60 |

1 Transitioning to ‘education for sustainability’

There are many different views on education for sustainability or sustainable development, where the latter term is more often used. A global goal for sustainable education is defined as part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) under Goal 4 Quality Education:

Target 4.7: By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development.

In this SDG (Quality Education – Target 4.7) sustainable development is clearly stated alongside issues of social equity, diversity, and global citizenship. Less emphasised is the environmental imperative and the relevance of ecological literacy in understanding and responding to the climate crisis. Historically, environmental education and environmental citizenship have been identified as important areas of education for sustainability.

1.1 Environmental education

The concept of environmental education was first formalised by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 1970 and further supported by the establishment of the International Environmental Education Programme (IEEP) in 1975, following the recommendation from the United Nations (UN) conference on Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972.

The United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) convened the first intergovernmental conference on environmental education in Tbilisi in 1977, to unanimously declare the significant role of environmental education in the preservation and improvement of the world's environment, and in supporting equitable global development. Known as the Tbilisi Declaration, it built on the Belgrade Charter (UNESCO, 1975) that defined the goal of environmental education (EE):

To develop a world population that is aware of, and concerned about, the environment and its associated problems, and which has the knowledge, skills, attitudes, motivations, and commitment to work individually and collectively toward solutions of current problems and the prevention of new ones.

The Tbilisi Declaration promoted clear goals and objectives of EE and defined a series of guiding principles (Box 1).

Box 1 Guiding principles for environmental education – Tbilisi Declaration (1977)

Environmental education should:

- consider the environment in its totality – natural and built, technological and social (economic, political, cultural-historical, ethical, esthetic);

- be a continuous lifelong process, beginning at the preschool level and continuing through all formal and non-formal stages;

- be interdisciplinary in its approach, drawing on the specific content of each discipline in making possible a holistic and balanced perspective;

- examine major environmental issues from local, national, regional, and international points of view so that students receive insights into environmental conditions in other geographical areas;

- focus on current and potential environmental situations while taking into account the historical perspective;

- promote the value and necessity of local, national, and international cooperation in the prevention and solution of environmental problems;

- explicitly consider environmental aspects in plans for development and growth;

- enable learners to have a role in planning their learning experiences and provide an opportunity for making decisions and accepting their consequences;

- relate environmental sensitivity, knowledge, problem-solving skills, and values clarification to every age, but with special emphasis on environmental sensitivity to the learner's own community in early years;

- help learners discover the symptoms and real causes of environmental problems;

- emphasize the complexity of environmental problems and thus the need to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills;

- utilize diverse learning environments and a broad array of educational approaches to teaching, learning about and from the environment with due stress on practical activities and first-hand experience.

The ambition for environmental education in the context of sustainable development was further promoted in the Agenda 21 framework generated as a result of the Earth Summit (UN Conference on Environment and Development) held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1992, where a reorienting of education towards sustainable development was developed (Box 2). After this event the UK created a Sustainable Development Education Panel (SDEP) to look at the development and application of Agenda 21 across levels of education and proposed seven concepts of sustainable development (Box 3) to be covered across wide-ranging curricula.

The different agreements and policy initiatives are evidence of growing calls for a much-needed transition in education. They are a window on some key initiatives of education for sustainability over the last 50 years that show a common pattern calling for an environmental imperative to be integrated within formal, and informal learning structures. Core to these calls for education for sustainability is the importance of seeing sustainability in the round and its:

- concepts and complexity

- multi-scale

- diversity

- interdependency of systems

- inter and intra-generational impact

- local and global

- the rights of human and non-human

- equity and justice

- citizenship

- stewardship

- precautionary approaches.

These components describe the various facets (the ‘what’) of education for sustainability over a 50-year period. However, the concept of transition requires us to not only scope the agenda but to actualise change through practice. The rest of the unit will explore the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ of education for sustainability.

Box 2 Agenda 21 Chapter 36 – Basis for action

36.3. Education, including formal education, public awareness and training should be recognized as a process by which human beings and societies can reach their fullest potential. Education is critical for promoting sustainable development and improving the capacity of the people to address environment and development issues. While basic education provides the underpinning for any environmental and development education, the latter needs to be incorporated as an essential part of learning. Both formal and non-formal education are indispensable to changing people's attitudes so that they have the capacity to assess and address their sustainable development concerns. It is also critical for achieving environmental and ethical awareness, values and attitudes, skills and behaviour consistent with sustainable development and for effective public participation in decision-making. To be effective, environment and development education should deal with the dynamics of both the physical/biological and socio-economic environment and human (which may include spiritual) development, should be integrated in all disciplines, and should employ formal and non-formal methods and effective means of communication.

Box 3 Seven concepts of sustainable development

- Interdependence – of society, economy and the national environment, from local to global

- Citizenship and stewardship – rights and responsibilities, participation and co-operation

- Needs and rights of future generations

- Diversity – cultural, social, economic and biological

- Quality of life, equity and justice

- Sustainable change – development and carrying capacity [the number of people, animals, or crops which a region can support without environmental degradation]

- Uncertainty, and precaution in action

Activity 6.1 Actions towards education for sustainability

This section has highlighted some of the environmental and sustainability education agendas over a 50-year period.

3. ![]() Select three adaptations and three challenges and share them with your peer online learners in the Activity 6.1 forum discussion.

Select three adaptations and three challenges and share them with your peer online learners in the Activity 6.1 forum discussion.

2 Exploring a transformative approach to learning

You have looked back across time at different perspectives on education for sustainability. This overview illustrates the legacy of education transitions that have aimed to address sustainability agendas. Such perspectives highlight the urgent need to scope, integrate and apply sustainability concepts in both formal and informal learning spaces. UNESCO (2017) identifies eight sustainability competencies and highlights the importance education plays in meeting global sustainability goals. Their sustainability competencies include:

- systems thinking

- anticipatory (future thinking)

- normative (values thinking)

- strategic thinking

- collaboration

- critical thinking

- self-awareness

- integrated problem solving.

The characteristics that underpin these competencies show a shift from specialism and seeing things in disciplines and parts, to a more integrative, holistic and relational thinking that values patterns and new ways of approaching uncertainty and complexity.

These competencies and associated knowledge and skills are critical for the (green) economy that new graduates will enter. This is an emergent economy with many unknowns. We are in transition, journeying across paradigms from industrial to information to the emergent structures of organisms as an organising paradigm. Humans have experienced great shifts in knowledge, skills and technology over a relatively brief period of history, and on a minuscule scale in geological time. Educators have yet to catch up. What is needed is an education paradigm that shakes off its original brief of delivering skilled people for industrial service. Education must reframe its learning scope as systemic, holistic, relational and transdisciplinary to meet the needs of sustainability in the twenty-first century. The sustainable education transition cannot be achieved with the same thinking that created unsustainability through earlier (and current) practices; we need a wisdom revolution to proliferate effective, sustainable transitions (Sterling, 2001). This is the ‘why’ of sustainable education transitions. The ‘how’ is perhaps the most difficult to grapple with.

Educationalist, Sterling (2001), asks educators to consider how we can design an ecological paradigm for education. He presents three different elements which need to be considered in this new educational paradigm:

- Ethos – where education is reoriented to reflect ecological thinking in terms of education theory, research and practice: in other words, how is education perceived?

- Eidos – how do the organising structures of education align with whole systems thinking and how can they recognise the importance and value of new patterns of relationship: in other words, how do we connect?

- Praxis – how teaching and learning approaches embed a systems view of the learner and develop participatory and transformative practices – in other words, how do we integrate?

Perhaps similarly to the sustainability competencies outlined by UNESCO, Sterling suggests a number of characteristics of the ecological education paradigm (transformative education) in contrast to the more mechanistic view (transmissive education) that dominates in education today (see Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of transmissive and transformative education practice and policy

| TRANSMISSIVE | TRANSFORMATIVE | |

|---|---|---|

EDUCATION FOR CHANGE (Practice) | Instructive | Constructive |

| Instrumental | Instrumental /Intrinsic | |

| Training | Education | |

| Teaching | Learning (Iterative) | |

| Communication of message | Construction of meaning | |

| Interested in behavioural change | Interested in mutual transformation | |

| Information – one size fits all | Local and/ or appropriate knowledge | |

| Control centralised | Local ownership | |

| First order change* | First and second order change* | |

| Product oriented | Process oriented | |

| Problem solving – time bound | Problem reframing – iterative change over time | |

| Rigid | Responsive and dynamic | |

| Factual knowledge and skills | Conceptual understanding and capacity building | |

| Imposed | Participative | |

EDUCATION IN CHANGE (Policy) | Top-down | Bottom up [often] |

| Directed hierarchy | Democratic networks | |

| Expert-led | Everyone can contribute expertise | |

| Pre-determined outcomes | Open-ended enquiry | |

| Externally inspected and evaluated | Internally evaluated, iterative process and externally supported | |

| Time-bound goals | Ongoing process | |

| Language of deficit and managerialism | Language of appreciation and cooperation |

Reflection

Reflection

Reflect on the characteristics of transformative learning in education practice and policy, presented in Table 1.

Which characteristics do you feel you already incorporate in your practice?

Which seem most urgent to incorporate to transition towards sustainable pedagogies?

Transformative learning demands new frames of thinking, being and doing. The ‘how’ of achieving this is indeed tricky and perhaps speaks to the fact the same agendas for sustainable and environmental education have been debated repeatedly, as we have shown, for the last 50-years, but ineffectively implemented, at least in mainstream education.

2.1 Systems thinking and new paradigms

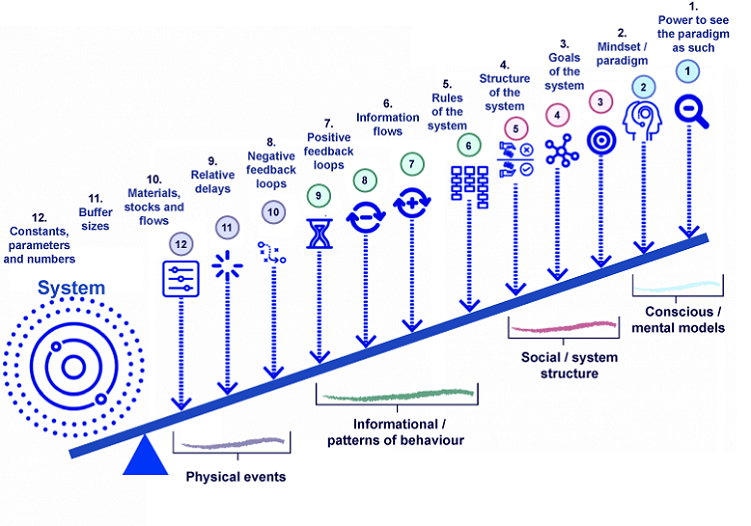

Systems thinker, Donella Meadows identifies the achingly difficult job of rethinking the present in terms of conceptualising system change through a series of intervention points. Although the paper was first published in 1999, it is still of great value in its ability to discuss the complex scope of systems change in ways that resonate with non-experts.

Meadows (1999) posits that there are several opportunities to intervene in a system but, society tends to only focus on ones that are familiar in terms of what is observed and understood and that resonate with known ways of evaluation and decision making. In broad terms this links to quantitative, visible stocks and resource flows and feedback that can be measured (in numerate ways), analysed and redistributed.

Figure 3 shows the points of intervention Meadows describes, with the current system on one side of the fulcrum, and points of system intervention reaching out on the other side. The nearer the intervention to the fulcrum, the less impact it has on changing system parameters (e.g. a force pushing down near the fulcrum has negligible impact on the system on the other side). Conversely, intervention opportunities far away from the fulcrum, once initiated, can make significant differences in system organisation where forces pushing down at the far end of the lever have greater impact (e.g. there is more leverage for pivoting the system to a different position (or paradigm)). Meadows shows that even small interventions can provide shifts in paradigms and many small changes at the right point in a system can have a big impact:

Paradigms are the sources of systems. ... There’s nothing necessarily physical or expensive or even slow in the process of paradigm change. In a single individual it can happen in a millisecond. All it takes is a click in the mind, a falling of scales from eyes, a new way of seeing. Whole societies are another matter. They resist challenges to their paradigm harder than they resist anything else.

A takeaway here is that change is impossible (or at least immeasurably difficult) if we try and make change in contexts where success, or not, is measured by existing ways of knowing and valuing.

Sterling’s call for a wisdom revolution is poignant in terms of creating new ways of seeing, being and doing, and in our case, of reframing education as sustainability (rather than just learning about it). So, the ‘how’ of change is going to require not only new knowledge but also the mechanisms, structures, organisation, policy, processes and communities to generate new curricula and learning practices that reflect the social system structures and conscious mental models of a new ecological paradigm.

Transformations in the way things are done depend on transformations in the way things are understood – in the worldview or perspective assumptions that condition those understandings.

This is a transition in practice.

Activity 6.2 Characteristics of transformative learning experiences

3. ![]() Share three opportunities or barriers to transformative education practice or policy with your peer online learners on the Activity 6.2 forum discussion.

Share three opportunities or barriers to transformative education practice or policy with your peer online learners on the Activity 6.2 forum discussion.

3 Designing eco-literacy for sustainable transitions

On the one hand Meadows says that small system interventions in the right place, can make a meaningful impact to systems change; on the other hand, Sterling (2001) gives a long list of comparisons between transmissive and transformative education practices which indicate the difficulties in shifting from one operating space to another. There are multiple ways of viewing the changes to systems required for an effective sustainable transition. At some point though, individuals must ask the questions:

- So, what can I do?

- How can I influence sustainable change as a citizen, an educator, a businessperson, a community worker, a parent, a grandparent, a friend, a child …?

- What is my role in moving us towards a sustainable future?

Amongst all the doom and gloom of predicted outcomes of a warming climate, hope and opportunity for new horizons and outcomes that transformative education can bring must be demonstrated. The UN poster designed to support UN SDG 4, shown in Figure 1 (repeated below), states ‘Education can change the world’. This last section begins to explore what this might mean and how you can be part of a new learning practice.

The European Union’s (EU) Horizon 2020 research project, CreaTures – Creative Practices for Transformational Futures, summarised in Video 1, is an interesting example of transdisciplinary responses to current social and ecological challenges. Its activities and outcomes result from an amalgamation of dialogue and exploration across different creative and critically reflective art and design practices, and related cultural fields.

The work shows the value of supporting transformational change by providing equitable spaces for discovery and building new networks and capacities. Participants’ imaginations provide a leaping-off point to other worlds and ways of seeing, and together sprout opportunities for different ways of existing in transition. As one participant articulates in the summary film, ‘It is important to realise that there is no future that would look the same for everyone and there is just a shared sense of urgency’ (CreaTures EU, 2023, 2:05 minutes).

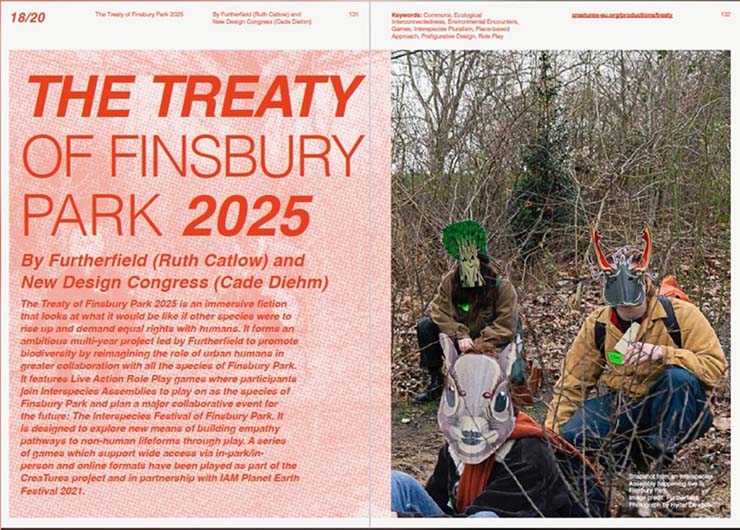

One of the projects supported by CreaTures is the ‘Treaty of Finsbury Park 2025’ (Figure 4) which explores new ways to build empathy to non-human lifeforms through play. The five-year project focuses on a local green space, Finsbury Park, and develops creative and playful ways such as an immersive, role-play festival, through which connecting communities can nurture a much deeper understanding of that green space and its human, animal, fungi and plant inhabitants.

The CreaTures project certainly has resonance with many of the elements of transformative practice: from construction of meaning and capacity building, to open-ended enquiry, emergence and processes of iteration. Alongside transformative learning characteristics, Sterling calls for the ecological design of education for sustainability. He asks the question ‘How can we design in an open and non-deterministic way, educational systems and institutions that promote healthy emergence?’ (Sterling, 2001, p. 80).

Design as a reflective and iterative practice should enable such reflective action towards a vision and purpose, that includes the core values and ideas underlying it, to deliver sustainable education. However, to date, there has been little evidence of success in this area. While there has been significant scoping and agenda setting around education for sustainable development (ESD) there has only been marginal examples of integrated and emergent transformative education practices. There are various reasons for this but one big one must be the chasm that exists between the values, structures, and measurement of existing, transmissive education, compared to an education ethos of a transformative learning approach.

3.1 An ecological design approach

The rest of this section takes an ecological design approach to explore how transformative learning practices may be imagined and integrated.

Architects, Sim Van der Ryn and Stuart Cowan, established a series of ‘principles of ecological design’ (Box 4). While these are generally reflective of design practices and processes associated with people, buildings, landscapes, and places, they nonetheless provide a useful stimulus to design ‘education as sustainability’.

Box 4 Principles of ecological design

Principle 1: Solutions grow from place – this is the counter view to the dominant one that supports centralisation and standardisation, economies of scale and decisions in isolation from a context of practice.

Principle 2: Ecological accounting informs design – we have become removed from, and ignorant of, natural systems of resource and waste flows in favour of solutions dominated by economic costs. Ecological accounting traces all ecological costs (resource depletion, pollution, habitat loss), to address system impacts.

Principle 3: Design with nature – a regenerative approach; to understand and work with the patterns and processes favoured by the living world to limit the ecological impacts of our activities.

Principle 4: Everyone is a designer – understanding the value of listening to shared experiences, knowledge, values and needs. Diminishing the idea of expert in favour of participatory process, dialogue, emergence, and action.

Principle 5: Make nature visible – developing an understanding of our place in nature and in the systems that support us. Create opportunities for engagement, responsibility, and accountability.

(Van der Ryn and Cowan, 1996, pp. 72–74)

How might we apply these principles to creating an eco-literacy practice in education?

We have seen through the work of Sterling (2001) that design should be a continuous learning process, and through Meadows (1999), that interventions to system change can be small and radical to enable a paradigm to shift at scale. Considering the large leap in underpinning ethos between transmissive and transformative modes of learning, the ecological design of education needs to frame the overview as well as enable smaller steps to be taken towards sustainable transition.

Let’s take the theme of ‘habitat’ as an illustrative example of a learning activity for school-age learners.

3.2 Learning about sustainable habitats

A series of lessons designed to foster eco-literacy in children are given here as an example for the learning experience you are asked to design in Activity 6.3 that follows.

Objective: To foster eco-literacy through a transformative learning approach that encourages students to observe, reflect, and learn from their relationship with the environment, creatures and their different habitats.

UK Key Stage 2 (ages 7–11)

Learners may be introduced to the habitat concept through narratives of different creatures, their environment, and their needs. The principles of ecological design (Box 4) can help frame these activities.

Lesson 1 Observe different habitats of different creatures

- Principle 1: Solutions grow from place –

Use the school grounds to observe and record different insects, birds and mammals.

Develop a shared storyboard of what you see and what you can research about the non-humans that share the playground.

Discover different habitats, patterns of hibernation and migration, and food sources.

Represent and collate information in drawings, photographs, role-play, stories and myths, and convene opportunities for small group working.

Lesson 2 Understand the design of sustainable habitat

Principle 3: Design with nature –

Explore different creature habitats and their locations.

Introduce contextual information about sustainable living and sustainable habitats.

Discuss how different habitats are constructed and why (e.g. in a high place or hidden under logs) and build an understanding of other things that might influence characteristics of habitat, for example:

- protection

- food sources

- weather

- temperature

- wind

- predators.

Think about how creatures’ habitats differ from our own. This helps learners to think about how different materials meet different needs and the importance of understanding local conditions.

Lesson 3 Co-creating your creature’s habitat: prototyping and storytelling ‘a day in the life of …’

Principle 4: Everyone is a designer –

If your creature was looking for a new habitat, how would you design and build it? Facilitate small groups to create ideas for a selected creature’s new home.

Use their research to support story boards and perhaps role-playing to understand what the creature’s needs are, and if they can be met in the design of a new home.

Explore different materials to co-create a creature’s habitat indicating key characteristics and features.

Activity 6.3 Create an eco-literacy learning activity

This activity asks you to design an eco-literacy activity for adults or school-age learners to explore the theme of habitat in more critical ways and explore ideas of regenerative design and the circular patterns of resource flows practiced in nature. The idea is to clarify the contrast between the linear resource flows that make human ‘developed’ systems and infrastructures of place unsustainable and the circular patterns of resource flows in nature.

For example, ‘Principle 2: Ecological accounting informs design’ and ‘Principle 5: Make nature visible’, can be used to illustrate differences between creature habitat and our built environment that highlight the unsustainable consequences of linear and invisible resource flows in developing new structures and systems of service.

The structures of human-made buildings could be considered alongside the structures of creature habitats. Human-made structures often rely on global supply chains and creatures’ habitats always rely on local resources.

Energy and water systems of buildings are hidden (e.g. toilet waste or grey water waste are not generally visible, nor is the energy that goes into making things work) so this makes their value and impact on supporting us seem invisible, whereas creatures rely totally on their immediate habitat.

1. ![]() Inspired by the five principles of ecological design, create a playful eco-literacy activity.

Inspired by the five principles of ecological design, create a playful eco-literacy activity.

Think about what you want to achieve, the structure and focus of the activity and who the learner audience is, then decide which principles your activity will align with.

You can present the activity in a number of different ways, for example, as a:

- list

- map

- storyboard

- image.

We encourage you to consider which aspects of your activity align with a transformative learning approach.

2. ![]() Present your activity idea in the Activity 6.3 forum discussion.

Present your activity idea in the Activity 6.3 forum discussion.

4 Summary of Unit 6

Sustainability requires changes in the way we think and conceptualise ourselves as part of nature, rather than having dominance over it. In education terms it is important that this ethos begins early and, as educators, our challenge is to introduce important relational thinking to learners in creative, exploratory and playful ways as part of a transformative learning landscape to support sustainable transitions.

In this unit you have looked at what it means to develop eco-literacy and why doing so is so important. You looked back to how the concepts around sustainability have been developed and thought about your own understanding of sustainability, then considered where the points of leverage are within a system that could allow the system to become more attuned to sustainability. You finished the unit by designing learning that would allow the learners you teach to develop their eco-literacy.

Unit 6 cards

Click/tap each card to reveal the text.

Continue to Unit 7: Ecological wisdom in traditional knowledge.

References

Catlow, R. and Diehm, C. (2020) ‘The Treaty of Finsbury Park 2025’, New Design Congress (10 April). Available at: https://newdesigncongress.org/ en/ pub/ finsbury-park-2025/ (Accessed: 10 March 2024).

CreaTures EU (2023) CreaTures (short version). 13 January. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=iBDmPn4Am_s (Accessed: 10 March 2024).

EU Horizon 2020 (2020) CreaTures – Creative Practices for Transformational Futures. Available at: https://creatures-eu.org/ about/ (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Fear, F. A., Rosaen, C. L., Bawden, R. J., and Foster-Fishman, P. G. (2006) Coming to Critical Engagement – An autoethnographic exploration. Maryland: University Press of America, Lanham.

Goleman, D. Bennett, L. and Barlow, Z. (2012) Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating, Emotional, Social and Ecological Intelligence. The Center for Ecoliteracy, San Fransisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Meadows, D. (1999) Leverage points: places to intervene in a system, Hartland, VT: The Sustainability Institute. Available at: https://donellameadows.org/ archives/ leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/ (Accessed: 4 September 2023).

Sustainable Development Education Panel (SDEP) (1998) First Annual Report 1998/ A Report to DfEE/QCA on Education for Sustainable Development in the Schools Sector from the Panel for Education for Sustainable Development - 14 September 1998, SDEP/DEFRA. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ 20080305115859/ http://www.defra.gov.uk/ environment/ sustainable/ educpanel/ 1998ar/ ann4.htm (Accessed: 11 December 2023).

Sterling, S. (2001) Sustainable Education – Re-visioning learning and change. Schumacher Briefing no. 6. Schumacher Society/Green Books, Dartington. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/ Sustainable-Education-Re-visioning-Schumacher-Briefings/ dp/ 1870098994 (Accessed: 11 December 2023).

UNESCO (2017) Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. Paris: UNESCO. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ images/ 0024/ 002474/ 247444e.pdf (Accessed: 11 December 2023).

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (n.d.) Core Publications – Agenda 21 Section IV Means of Implementation, Division for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/ content/ dsd/ agenda21/ res_agenda21_36.shtml (Accessed: 6 March 2024).

UNESCO–UNEP (1978) Inter-governmental Conference on Environmental Education, 14–26 October 1977, Tbilisi, USSR: UNESCO–UNEP, Paris, France. Recommendation 2, pp. 27. Available at: https://www.gdrc.org/ uem/ ee/ Tbilisi-Declaration.pdf (Accessed: 6 March 2024).

UNESCO-UNEP (1975) The Belgrade Charter: A Framework for Environmental Education:, UNESCO-UNEP International Workshop on Environmental Education at Belgrade, 13–22 October 1975. Available at: https://www.eusteps.eu/ wp-content/ uploads/ 2020/ 12/ Belgrade-Charter.pdf (Accessed: 6 March 2024)

Van der Ryn, S. and Cowan, S. (1996) Ecological Design. Michigan: Island Press.