Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 11:45 PM

Section 3: Nurturing connections – building positive relationships

The role of relationships

‘Relationships always underpin everything. Always invest in them.’

In this section, you will explore how personal, community, and workplace relationships support others in overcoming stressors and trauma. You will learn how to nurture relationships and build meaningful connections, especially with those who have experienced trauma.

This learning will provide examples of trauma-informed, relationship-based practices and explore how people and organisations can develop their approach accordingly.

Throughout this learning, the terms ‘relationship-based practice’ and ‘relationship-based approach’ are used interchangeably. While they may seem relevant only to workplace practices, it is essential to recognise that relationship-based principles apply universally within all interactions. Whether termed as a practice or an approach, the focus is on valuing and nurturing relationships to enhance communication, cooperation and well-being. Understanding this broad application highlights that positive relationships enrich both personal and professional lives.

At both the individual and community levels, relationships are the cornerstone of everyday interactions and central to our lives. We are surrounded by relationships, whether with immediate and extended family, friends, acquaintances, pets, community leaders, schoolteachers, healthcare staff and many others. No matter the specific context of a relationship, what they all have in common is that they provide the foundations for how others relate to you and you relate to them, and how well you can respond to and support each other.

This also applies to the care system where good relationships help to improve current and future experiences for children and young people. When we get it right, children and young people will have more opportunities to thrive and they are more likely to do well in school, have good mental health and succeed at work.

Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

After completing this section, you should be able to:

Explain how personal, community, and professional relationships contribute to positive emotional well-being and outcomes for those impacted by trauma, and particularly the care-experienced population.

Apply positive relationship skills to enhance interpersonal connections and interactions. These include empathetic listening, boundary-setting, and strategies that create environments where individuals feel safe, valued and understood.

The box below provides a selection of course download options for use offline or on other devices.

3.1 Childhood – early life influences

‘Every child deserves a champion – an adult who will never give up on them, who understands the power of connection and insists that they become the best they can possibly be.’

In the previous section, you learned about Jemma and her experience of care and potential trauma.

Experience of trauma can overwhelm an individual's capacity to handle everyday situations, impacting their sense of safety, ability to self-regulate, and approach to forming relationships. Everyone’s upbringing, including their experiences of trauma, influences the relationships they have both in childhood and later in life.

Traumatic events in early childhood can influence not only the attachment style of the child but also their adult attachment style. Attachment styles describe the patterns of behaviours and expectations an individual demonstrates in relationships, and can affect the ways in which intimacy, trust, separation, and communication are handled.

3.2 Attachment theory

Attachment theory was initially put forward by John Bowlby, a psychologist at the Tavistock Clinic in London in the 1950s. His work focused mainly on children who had been separated from their parents (particularly mothers) in early childhood due to prolonged hospital stays, as well as children living in children’s homes.

Bowlby’s work was set within the time frame following the Second World War where many children had lost parents or were temporarily separated from them as evacuees due to bomb threats in large cities. What was ground-breaking about Bowlby’s work at the time was that for the first time the emotional health of children was being considered as equally important as their physical health for their overall well-being (Bowlby, 1969).

The most effective way to visualise attachment is as a process. Through the development of close, caring and positive relationships in childhood, a young child can build up an effective internal set of ideas or what has been called an internal working model of how they see themselves, how they interact with others, and also how they develop their own sense of who they are and who they can become within the social world around them.

The following diagram shows the interconnections between self, other and the world in order for the young child to build up an internal working model of how relationships work.

Reflecting on the diagram and the questions that might be asked or addressed through different interactions, you might go back to Jemma’s journey through care and notice how different ways of being attached or connected to significant others, may have affected Jemma’s beliefs about herself, the world around her, as well as her sense of self.

Consistent, warm and loving connections with significant caregivers, who have been attuned to their emotional needs, can support individuals to develop secure and positive attachments with others. By being given positive acceptance for who they are, individuals are more likely to grow up feeling they are worthy of other people’s attentions and can express their emotions more openly. This can then help individuals to be better prepared to make positive contributions to relationships with others in the future. They are also more likely to trust their own emotions and perceptions as well as accept the support of others.

Activity 2: Trauma-informed lens

Activity 2: Trauma-informed lens

In this activity, you’ll use your ‘trauma-informed lens’ to understand and recognise how trauma might influence behaviours. While not all behaviours stem from trauma, it’s important to consider trauma’s potential impact before forming conclusions.

When we use our trauma-informed lens and consider the role trauma may be playing in how Jemma may be behaving at school, we start to think and talk about her and her behaviours differently.

Think about Jemma’s experiences of starting a new secondary school.

This was the hardest part of moving homes as she was in classes with children that she didn’t know, and changing teachers meant that her learning was different. Her new classmates knew that she was in care, and this made Jemma feel uncomfortable.

Imagine, for the purpose of this exercise, some of Jemma’s responses at school were labelled ‘manipulative’ or that she appeared disinterested, was seen to fidget and avoid eye contact and conversation.

What if teachers had said that Jemma had understood her learning but wouldn’t engage with other pupils who were trying to engage with her and viewed her as ‘disrespectful’, or that they feel frustrated and say that Jemma is ‘lazy’ because she puts her head down and attempts to sleep during class?

By completing this activity, you have practised reframing behaviours through a trauma-informed lens which fosters empathy and creates environments where individuals feel understood and supported.

The trauma-informed approach encourages compassion, minimises judgement and promotes supportive and trusting relationships.

3.3 Relationships

All relationships look different depending on who they are with, but one thing that all relationships should have is respect and a two-way balance of understanding.

Relationships can foster healthy interactions and well-being, as well as develop growth and recovery, but they can also cause harm.

Positive relationships are characterised by mutual respect, trust, and empathy, fostering emotional well-being and personal development – other relationships marked by abuse and neglect may lead to distress and trauma.

Self-care booklet

Self-care booklet

The course also emphasises the value of looking after yourself and knowing where to find further help and support for anyone who needs it.

You may find this self-care booklet useful.

What can affect relationships?

Differences in wealth and resources – and societal inequalities such as race, gender, religion, education, and more – can have a deep impact on relationship-building and engagement.

Recognising these factors is central to relationship-based approaches as it ensures that everyone’s situation is considered, and this helps to support meaningful and supportive interactions.

Understanding these factors can help nurture healthier relationships for those with lived experience of care.

3.4 The importance of positive relationships from a care-experienced lens

Everyone has positive and negative interactions and relationship experiences, but we know that positive relationships are crucial to well-being because they boost emotional and physical health.

Using the trauma-informed principles in everyday life can help to build trust, respect and supportive relationships, empowering individuals to grow and thrive long term.

This concept is explored further below where East Lothian Champions Board talk about the importance of positive relationships and delegates at the Children in Scotland conference discuss what relationship-based practice means to them.

East Lothian Champions Board

East Lothian Champions (Champs) Board is a group for young people aged 12+ making change to local policy and creating a sense belonging for young people who have experience of care (East Lothian Council, 2024).

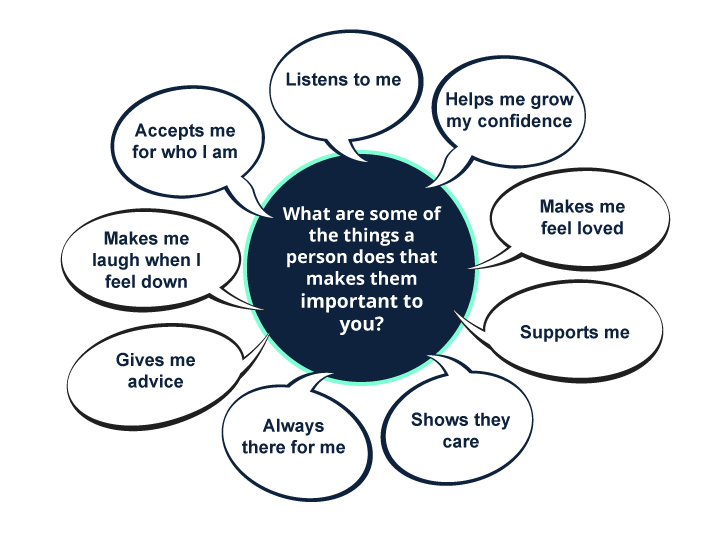

The Champions Board shared their thoughts about how positive relationships made them feel. The key points were that they felt cared for, understood, heard, safe, loved, wanted, important, happy and confident.

This is what the Champs Board said.

Click on the play button below to listen to and read the three quotes.

Champions Boards were funded from 2016 to 2019 by the Life Changes Trust care-experience programme and their legacy work is available to see on Staf’s Life Changes Trust Resource Hub.

To find out more, explore Resources for professionals, shaped by young people with care experience.

Care experience and relationship-based approach

At a development workshop, at the Children in Scotland conference May 2024, people who work with the care-experienced community explored, ‘what comes to mind when you think about relationship-based practice?’ Here’s what they said:

Feedback from both the workshop and the East Lothian Champions Board, highlighted that positive relationships can improve well-being. It also emphasises the importance of the trauma-informed principles – safety, trust, choice, collaboration and empowerment in relationships.

This would be a good opportunity to consider the principles and how they can be used to better strengthen relationships and approaches.

All children and young people will have different relationships throughout their lives. Children and young people with experience of care may have the following types of relationships that make up their scaffolding of support. (Scaffolding is a tested metaphor that helps people understand all the different components of support that exist within the ‘care system’.)

3.5 Informal relationships

In this section, we'll look at why family, friendships, pets and animals, and objects and belongings are so important.

Family – who is important?

It’s essential to recognise that the definition of family can vary greatly among individuals, depending on their unique circumstances and situations.

‘Family’ typically refers to a group of individuals connected by blood, marriage, or adoption, often living together or maintaining close, supportive relationships. Other ‘family’ can include chosen relationships, such as close friends or community members, who provide similar support and connection.

For children and young people with experience of care, the idea of ‘family’ can be complex, therefore, it’s important for them to have the opportunity to choose their own trusted relationships and have those prioritised and supported as far as possible. We know that these connections offer emotional stability, a sense of belonging, and a foundation for personal growth.

Consider Jemma’s experience of family and what this could have meant to her.

Friendships

Our friendships can provide emotional support, companionship, and a sense of belonging.

The Care Experience and Friendship Insight Summary (Roesch-Marsh and Emond, 2022) explores this concept and highlights the following key points:

- The desire for friendship is common to most children and young people.

- A lack of supportive friendships is linked to poorer health and well-being.

- Friendship can be defined in many ways.

- People with care experience should have the same opportunities for friendship as others.

- Adults should recognise how important friendships are for children when making plans.

If you would like to learn more, Roesch-Marsh and Emond discuss this further in the following webinar (University of Strathclyde, 2023). You may wish to view the whole webinar (90 minutes) but if you only want to watch Professor Emond and Dr Roesch-Marsch's presentation, this can be viewed from 42:43 onwards.

Pets and animals

The University of Edinburgh (2022) carried out a study to explore the significance of pets for children and young people with care experience and the impact of disruption to those relationships when moving between homes.

Children and young people who took part in the study highlighted the importance of pets in their lives, such as:

| Mental health support (physical and emotional). |

| Companionship/prevents loneliness. |

| Non-judgemental/good listeners. |

| Physical exercise/engagement with outside world. |

| Need to nurture/receive unconditional love. |

| Pets can provide a secure base. |

| Relationships with pets may be stronger than those with other family members. |

| Pets can support the transition to independent living and care leavers’ mental health. |

If you would like to learn more, you can read the study in more detail (The University of Edinburgh, 2022).

Objects and belongings

For children and young people with lived experience of care, objects and belongings can be especially important because they can provide a sense of continuity, comfort, and personal identity.

These items often carry emotional significance and can help children feel connected to their past and maintain a sense of stability during transitions. Having familiar belongings can offer reassurance, ease feelings of displacement, and support emotional well-being.

If you would like to learn more, Who Cares? Scotland explore this in more detail in podcast interviews with care-experienced individuals (Armitage, 2021).

Take time, to reflect on Jemma’s experience of leaving her family home with her belongings. As part of its ‘My Things Matter’ campaign, the National Youth Advocacy Service (NYAS) have conducted extensive research (NYAS, 2022) with care-experienced young people to delve deeper into this.

If you would like to learn more, you can read about it in more detail.

3.6 Formal relationships

In this section, we'll look at corporate parents, education and the workforce.

Corporate parents

Not everyone has an understanding of the term ‘corporate parent’.

‘A corporate parent is a name given to an organisation or person who has special responsibilities to care-experienced children and young people.’

Corporate parents are especially important because of the vital role that they hold in their lives.

Corporate parent services include housing, education, healthcare, and social support that work together to create opportunities and a caring environment for children in care to thrive.

Education

We know that in educational settings, positive teacher–pupil relationships promote a safe and supportive learning environment. This approach can help to create consistency and stability for children and young people with care experience.

The following video discusses the importance of relationship-based and trauma-sensitive practice.

‘Being trauma-sensitive is about having wonderful relationships with everyone in our school community.’

‘I’ve been in the profession for 34 years. I haven’t always thought like that. It’s taken me a long time to come to this realisation. They are all our young people, and it is up to us to change and to work differently and to understand better so that we can support every young person.’

Workforce

The workforce must ensure that they provide a high level of care and support for children and young people and that relationships are supported to continue through and beyond care.

The ‘workforce’ includes:

- Social workers.

- Health workers.

- Teachers.

- Youth workers.

- Family support workers.

- Kinship and foster carers (who may regard their role to be professional or vocational).

A trauma-informed organisation understands that nurturing positive relationships among colleagues, and between managers and employees, fosters a safe and trusting work environment and a shared vision of good practice.

‘The personal and the professional must not be seen as two different things; the workforce must be supported to be human with the people they work with.’

In this podcast (21 minutes), The Forum (2019), Pamela Graham of the Scottish Throughcare and Aftercare Forum (STAF), talks to Pauline Connelly of Tremanna, a children’s home near Falkirk in Scotland, about how nurturing positive relationships has supported the delivery of a unique model of care at the home for children and young people.

3.7 Positive relationship skills

Relationship skills are needed by everybody – they will enable you to connect with others and form bonds. They can help you to have healthy, happy and strong interactions with people.

By offering stable, positive relationships, the right support and calming environments, this can help to build resilience for children and young people.

Watch this video which explains how this can be done.

Different skills are required for different types of relationships and situations.

Look at the scenarios in the relationships below.

Click on each of the six headings to learn more.

Think about how you could develop these suggested strategies and techniques further to achieve positive relationship skills.

Boundaries

What do we mean by boundaries?

Personal boundaries are limits we set to protect our emotional and physical well-being in relationships. Good boundaries can help to build positive relationship skills, and they can help us to stay within our window of tolerance. It is important to be mindful of our own boundaries and the boundaries of the person you are supporting, as they need to feel emotionally safe, and this may not be easy for them.

We may avoid setting boundaries due to the fear of feeling uncomfortable. However, there is kindness in the use of boundaries – it is kind action to take as it promotes respect and clarity. It’s ok to say ‘no’ and this can help you to become better at setting and maintaining boundaries.

Creating emotional safety

Emotional safety is essential for positive relationships in any setting. When people feel listened to and understood, they feel safe, appreciated, valued, worthwhile, and trusted. This allows them to feel vulnerable and take responsibility for their actions.

In emotionally safe relationships, people feel comfortable around each other, can share thoughts and opinions, repair conflicts quickly, express sensitive feelings and feel connected. We are all responsible for creating emotional safety – by using the trauma-informed principles in our everyday practice we are more likely to achieve this.

Listening with empathy

Empathetic listening improves collaboration, trust and builds connection. When somebody is listening empathetically to us, we are likely to be more open and less defensive.

Watch this short video with Brene Brown by the Royal Society of Arts (RSA, 2013) on empathy.

Listening with empathy means to:

| Pay attention – make sure the other person has your undivided attention. |

| Pause your talking – give time for the other person to share, don’t interrupt. |

| Maintain open body language – consider non-verbal communication and responses such as eye contact and posture. |

| Provide invitation to explore – ‘Please, let me know your views on this’, ‘I’m really interested to hear what you think’. |

| Listen for deeper meaning – ‘Take as long as you need, I’m here to listen’. |

| Acknowledge and validate – ‘That sounds really hard’, ‘It sounds like you’re dealing with a lot’. |

| Check your understanding – ‘So what you mean is’, ‘Let me make sure I’ve got this right’. |

Listening with empathy will help to create a space for people to feel safe. In addition to how you listen, it’s important to consider the language that you use too.

3.8 Language

‘Scotland must understand that ‘language creates realities’. Those with care-experience must hold and own the narrative of their stories and lives; simple, caring language must be used in the writing of care files.’

The language we use helps us to communicate our thoughts, feelings and ideas. Using language that is non-stigmatising and easily understood fosters an understanding and connection with the person you are communicating with.

Watch this video which explores the experiences of children and young people who have interacted with the Children’s Hearings System in Scotland. The video illustrates the importance of language and how saying and doing things differently can help to make a positive difference (Our Hearings Our Voice, 2024).

Each and Every Child explains how this can be done.

Each and every child should have what they need to feel safe, included and to thrive, now and in the future.

However, we know that stigma can impact on people with lived experience of care in all aspects of their lives. The wider public often do not always have a full understanding of all the different aspects of care experience and the care system, which can lead to assumptions about what’s happening.

These assumptions often are not accurate and are shaped by the way care experience and the care system is spoken about in media, culture and through our own work – the words that we use, and the ideas that we share.

Framing is the choices we make about how we tell stories: what we share and how we share them. It’s these choices that change how people think, feel and act. Each and Every Child exists to tell a different story about care experience and to support and guide everyone with a story to tell.

We draw on research from FrameWorks UK to share eight ways we can communicate about care experience and the care system that counter stigma and discrimination. These recommendations help build wider public understanding of care experience, and direct people to solutions that will create meaningful and sustained change. They are simple, easy to use, and can be adapted to different ways of sharing information.

If you would like to learn more, you can explore the full toolkit.

Activity 3: Positive relationship skills

Activity 3: Positive relationship skills

In this activity, you will enhance your understanding of positive relationship skills which are essential for fostering trust, safety and connection, particularly for those with experiences of trauma, like Jemma.

By completing this activity, you've strengthened your understanding of positive relationship skills essential for fostering trust and safety, particularly for those who have experienced trauma.

You’ve identified the skills needed for a trauma-informed approach which not only nurtures a compassionate environment, but paves the way for meaningful, supportive relationships that can impact the journey toward healing.

3.9 Summary

In this section you have learned about relationships and in particular:

- The importance of positive relationships and relationship skills.

- Attachment Theory and how attachment affects children and adults.

- The types of relationships, including formal and informal.

- How setting boundaries can help to protect our emotional and physical well-being in relationships.

- How emotional safety is essential for positive relationships in any setting.

- How listening with empathy helps to build collaboration, trust and connection in relationships.

- The importance of language and how saying and doing things differently can help to make a positive difference in relationships.

Moving on

When you are ready, you can move on to Section 4: Making it happen – turning knowledge into action.