Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 9 February 2026, 4:53 AM

Isolating and identifying bacteria (animal health)

Introduction

In this course, you will learn about microbiology techniques for isolating and identifying bacteria from clinical specimens collected from farm animals, including bacteria of interest for

Basic knowledge of concepts related to bacterial infection, growth and structure is assumed. If you would like a refresher course on these concepts, you might look back at the Introducing Antimicrobial Resistance course or this Microbiology textbook (OpenStax, 2021).

After completing this course, you will be able to:

- rationalise specimen collection protocols with the aim of improving the effectiveness of the bacteriology diagnostic laboratory

- evaluate how different types of specimens, and their quality and condition, may impact the performance of microbiological tests

- describe the principles of laboratory tests used to isolate and identify the bacterial pathogens on which this course focuses

- critically analyse microbiological methods used by front-line veterinary diagnostic laboratories

- know when, why and how advanced testing (e.g. by mass spectrometry, automated systems and DNA-based tests) is used

- reflect on the importance of procedures designed to ensure the quality of laboratory work relating to isolating and identifying bacteria.

In order to achieve your digital badge and Statement of Participation for this course, you must:

- click on every page of the course

- pass the end-of-course quiz

- complete the course satisfaction survey.

The quiz allows up to three attempts at each question. A passing grade is 50% or more.

When you have successfully achieved the completion criteria listed above you will receive an email notification that your badge and Statement of Participation have been awarded. (Please note that it can take up to 24 hours for these to be issued.)

Activity 1: Reflecting on your current knowledge and skills

Before you begin this course, think about your current level of knowledge and skills in the areas covered in this course. You will have an opportunity to repeat this activity when you have completed the course. Do not worry if you lack confidence in some areas, as you are likely to develop it by studying this course. For areas where you feel fully confident, it is always good to refresh and update knowledge and skills.

Use the interactive tool to rate your confidence in these areas using the following scale.

- 5 Very confident

- 4 Confident

- 3 Somewhat confident

- 2 Slightly confident

- 1 Not at all confident

Try to use the full range of ratings shown above to rate yourself.

1 Specimens

In this course, the term ‘specimen’ refers to material collected from an animal for bacteriological analysis. Sample indicates a set of specimens collected for that purpose. This course focuses on clinical specimens. The actual collection of non-clinical specimens for AMR surveillance purposes is described in AMR surveillance in animals and Sampling (animal health).

1.1 Reasons to submit clinical specimens for bacterial isolation and identification

Bacterial isolation and identification through culture is valuable for disease diagnosis in the following situations:

- If it is more cost-effective or easier to use than non-culture-based diagnostic methods.

- If the pathogen cannot be accurately predicted clinically and its identification is likely to influence treatment/disease management decisions.

- As part of complex disease investigations or multifactorial/polymicrobial infections.

- If a farm

antibiogram is needed (hence the need to obtain an isolate). - If bacterial subtyping is required, for example, for surveillance purposes (hence the need to obtain an isolate).

- When a definitive

aetiological diagnosis is necessary by law (e.g. notifiable diseases).

However, bacterial isolation is not commonly used for the routine diagnosis of some important bacterial diseases of farm animals, and alternative diagnostic methods are used for various reasons.

Activity 2: Endemic bacterial diseases of animals where the diagnosis is usually made without bacterial isolation

Use the text box to list important animal bacterial diseases that are common in your area where the diagnosis is usually made without bacterial isolation and the reasons why.

Answer

Some examples are below; you may have others.

- Bovine tuberculosis is generally diagnosed via tuberculin skin testing as infections are subclinical and Mycobacterium bovis is a slow grower (long turnaround time of culture).

- Glasser disease of pigs is often diagnosed by

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) due to the fragility of Hemophilus parasuis which often dies in the specimens during transport. - Mycoplasma gallisepticum/synoviae infections in poultry are often diagnosed by means of PCR or serology due to the slow growth rate of these pathogens.

1.2 Types of specimens submitted for bacterial isolation

Animal health laboratories should be able to process of a wide range of specimens for bacterial culture.

Activity 3: Types of specimen

Make notes on the types of specimen that are sent to your microbiology laboratory for bacterial culture. Compare your response with the sample answer.

Answer

Your laboratory may receive some or all of the following specimens.

- Sick animals or whole carcasses submitted for necropsy

- Visceral organs

- Tissue

- Body fluids: milk, urine, blood/serum/plasma, synovial/pleural fluid

- Faeces

- Swabs from body secretions/fluids

- Scrapings (skin; tissue)

An example of the range of specimens processed by animal diagnostic laboratories can be found on this website.

1.3 Selecting specimens for submission

Specimens are submitted for bacterial culture based on the suspicion that they may contain pathogenic bacteria. Submission of inadequate specimens may compromise the accuracy of the laboratory test results.

It is important to consider factors which may lead to a false negative or false positive test result for bacterial growth.

1.3.1 Avoiding a false negative result

What factors might lead to no bacterial growth in the presence of a bacterial infection (false negative result)?

Answer

Dead, damaged or low bacterial numbers in the specimen may result in no bacterial growth even if the animal from which the specimen was collected had a bacterial infection.

Examples of situations which can lead to dead or damaged bacteria are:

- specimens collected from animals recently treated with antimicrobials

- specimens collected/transported in preservatives or disinfectants

- frozen specimens.

Examples of specimens that are likely to have small bacterial numbers are:

- pus from old abscesses

- specimens consisting of a few drops of fluid and swabs.

1.3.2 Avoiding a false positive result

What is the most common cause of a false positive result for bacterial growth?

Answer

Contaminated specimens will yield bacterial growth unrelated to the disease leading to a false positive result.

The anatomical sites of origin of animal specimens can be normally sterile or non-sterile. Sterile sites are sites where living bacterial cells are not normally found. Therefore, if a sterile site specimen is obtained

Examples of sterile site specimens are:

- cerebrospinal fluid

- blood

- pleural fluid

- pericardial fluid

- bone marrow

- joint fluids

- needle aspirates of closed lesions

- internal organs (except organs in direct contact with, or connected to the gut)

- aqueous humour of the eye.

Conversely, non-sterile site specimens present interpretive challenges. Very often the same bacteria colonising a healthy site are

Examples of non-sterile site specimens are:

- faeces

- milk (when the external teat canal is colonised with commensal bacteria)

- sinus tract specimens

- nasal swabs

- skin scrapes/swabs

- needle aspirate/swabs from open wound/abscess

- urine (except when taken by

cystocentesis ).

During the

Sick animals euthanised immediately prior to the

2 Specimen collection, labelling, preservation and transport

Proper specimen collection, preservation, labelling and transport are vital to ensure:

- an adequate specimen in terms of quality and quantity

- the specimen’s bacterial flora remains stable until arrival at the laboratory

- that the laboratory performs the most appropriate tests for each case

- that the case’s data can be used for disease diagnosis/AMR surveillance.

As you will learn later, failure to follow proper procedures can compromise laboratory test results and undermine confidence in bacterial culture results in different ways.

2.1 Specimen collection

Specimens submitted for bacterial isolation must be collected using sterile tools in strict aseptic conditions. Immediately after collection, each specimen should be placed in an individual, leak-proof jar or bag free of preservatives, fixatives, or any other substance with antibacterial activity.

2.1.1 Fluid/semi-fluid specimens

Most fluid specimens are inoculated by transferring a 5-20 µl aliquot into liquid or solid media. However, some procedures require larger volumes of inoculum, for example, when inoculating different types of media in parallel to enable the isolation of a range of pathogens with different nutritional requirements (see Section 4.3). Hence, specimens consisting of only a few drops of fluid are inadequate and at least 1 mL should be submitted.

Swabs absorb a limited amount of fluid and should only be used when fluids cannot be collected in containers, for example, genital secretions or when collection in a container is likely to introduce contamination, such as a

2.1.2 Solid specimens

Whole organs or pieces of viscera covered by the intact

- sufficient core material can be obtained for inoculation into different types of media

- the use of aseptic technique during necropsy will ensure the core material is not contaminated with bacteria (see Section 1.3.2)

When septicaemic sepsis is suspected, culture of bone marrow from a 6–10 cm of aseptically cut piece of rib, or from aseptically collected brain tissue, will often yield the bacterial cause of the infection, as these organs are less accessible to post-mortem invasion by commensals.

Specimens collected from animals recently treated with antimicrobials may contain sub-lethally injured bacteria that will not grow in the laboratory and should be avoided. What should the submitting professional do if this cannot be avoided?

Answer

Information about any antimicrobial treatment should be specified in the

Specimens collected from organs of animals euthanised using barbiturates are also suitable for bacterial culture, as barbiturates do not have an antibacterial activity.

2.2 The importance of proper labelling and form completion

The importance of proper specimen labelling and completion of the submission form cannot be overemphasised.

In a diagnostic investigation, all the specimens submitted on the same day from a single or multiple animals from the same farm that appear to have a clinically related condition, are of a similar age or belong to the same group, should be submitted using a single form, and the laboratory should consider them as a single case number. This will enable a holistic interpretation of the results.

Poorly completed submission forms, in particular when accompanying multiple specimens, may lead to misunderstandings with undesired consequences for correctly interpreting diagnostic results. In addition:

- Regulatory testing or testing for notifiable bacteria may require the use of official forms. Failure to submit them may elicit government sanctions.

- Incomplete submission forms may exclude the submissions from any applicable public subsidy.

- Most laboratories offer pre-defined testing panels for different syndromes. The lack of details such as animal’s age or clinical findings may result in unnecessary testing. For example, testing for entero-toxigenic Escherichia coli in calves older than 10 days of age is unnecessary as only younger calves are affected.

- Poorly completed submission forms often prevents the recovery of the information from the laboratory database for passive surveillance purposes.

Activity 4: Receiving and processing specimens in your workplace

Use the question prompts below to think about the clinical specimens arriving in your laboratory and how they are processed.

- Are multiple, related specimens taken on the same day from animals considered as a single case?

- How frequently are inadequate forms submitted, and what is the procedure if this happens?

- Is there anything that can be improved in your system?

Discussion

Guidance on the correct procedures to follow should be given in the appropriate

You may want to have a discussion with your laboratory manager if you notice omissions or errors in the SOP or have improvements to suggest.

2.3 Specimen preservation and transport

The composition of the specimen’s bacterial flora begins to change from the moment of specimen collection, and this change may undermine the diagnosis.

Potential consequences of suboptimal specimen preservation include:

- lethal/sub-lethal injury of fragile organisms – false negative culture result

- overgrowth of normal flora or environmental contaminants – false positive culture result, incorrect diagnosis

- pathogen overgrowth during transport – false semi-quantitative estimates of pathogen numbers.

Specimens should be refrigerated as soon as possible after collection to reduce bacterial replication. This is critical if testing involves semi-quantitative estimations of viable bacterial numbers, for example, as used for the bacteriological diagnosis of cow

What might happen if specimens are not kept cold?

Answer

If the cold chain is not maintained, contaminants or co-infecting bacteria may overgrow the pathogen, hampering its detection in culture. This is a serious problem for fastidious pathogens such as Haemophilus parasuis, that are easily overgrown by contaminants.

Storage by freezing has detrimental effects on bacterial viability and should only be used if specimens cannot reach the laboratory within 24 hours. Repeated freezing and thawing should also be avoided as the number of viable bacteria may fall below the limit of detection of culture.

Swab specimens should be transported in transport media designed to avoid desiccation, while specimens for anaerobic culture should be preserved in sealed containers immediately after collection until they can be cultured.

3 Specimen collection for farm-level diagnosis of bacterial infections

The identification of a contagious agent on a farm often triggers infection control measures aimed at mitigating the economic impact of the disease on the whole farm. The need to diagnose contagious diseases at the group- or farm-level and less so at the individual animal-level is, therefore, a distinctive feature of farm animal medicine.

Bacteriological culture may yield a true negative result (an uninfected animal) or a false negative result (no bacterial growth from a specimen collected from an infected animal). False negatives may be due to:

- a non-viable agent

- an imperfect sensitivity of culture

- the bacterium not being present in the specimen (intermittent shedding), or present in numbers that are below the

limit of detection (LoD) of culture – common situations in many infectious diseases.

Sampling strategies that can bypass these problems and may increase the testing regime sensitivity at the farm level are:

- analysis of multiple specimens

- pooling of specimens

- aggregate testing.

3.1 Analysis of multiple specimens

Although the sensitivity of a culture method remains constant across specimens, culturing in parallel multiple specimens increases the probability of detecting the agent on the farm. In other words, it increases the farm-level testing regime sensitivity. This is achieved without compromising testing regime specificity, as a culture’s specificity depends mainly on how stringent the bacterial identification method used is. Multiple specimens may be analysed from a single animal (for instance, analysis of visceral organs and faeces) or multiple animals.

The disadvantage of parallel analysis of multiple specimens is the high cost of testing compared with the cost of a single culture. An alternative option, if the pathogen is expected to remain viable in the specimen for 48–72 hours, is for the submitting professional to request an initial culture of one specimen, with further cultures conditional upon a negative result.

The advantage of parallel testing of multiple specimens is exemplified in the following hypothetical case.

Figure 3 shows the variation in the number of Staphylococcus aureus colony-forming units (CFU) per mL of milk over time in 10 goats, after an experimental infection with a S. aureus strain. The horizontal blue arrow represents the hypothetical limit of detection of culture. Note that none of the goats would be culture-positive in the first six hours post infection. All the goats would be positive between 12 and 24h. From then on, the number of positive goats varies over time, and analysis of multiple specimens can increase the probability of detecting at least one infected goat. Multiple specimen analysis does not compromise culture specificity as the organism is identified to the species level using the same method.

3.2 Analysis of pooled specimens

Pooling of specimens involves combining aliquots of individual specimens and testing the pooled sample. If the pool is negative, all the specimens are considered negative. If the pool is positive and one needs to know the status of each individual specimen, each specimen must be collected separately and then be tested separately. Specimens can be pooled from a single subject, for example, four milk specimens taken from four quarters of the same cow or from different animals.

What are the advantages of pooling specimens?

Answer

Advantages of specimen pooling can include:

- reduced cost (test all for the price of one)

- increased farm-level testing sensitivity when it is uneconomical to test each animal separately

- detection of multiple pathogens (co-infections) at the farm level, without the need to test all the specimens for all the pathogens.

The disadvantage of pooling is that the number of bacteria in each combined specimen is diluted. Thus, if the bacterial load is small, the bacterial numbers may fall below the LoD of culture. Hence, the decision on pooling must be taken on a case-by-case basis considering the dilution effect.

3.3 Analysis of aggregate samples

The analysis of aggregate samples uses material widely available on the farm, rather than blends of specimens from a known number of subjects as in the case of pooled specimens.

Examples of aggregate samples that can be used for analysis are:

- manure samples

- feed samples

- tank milk samples.

What is the main advantage of analysing aggregate samples?

Answer

Using aggregate samples enables a cost-effective screening of large number of farms for many different pathogens without the elevated costs of sampling.

An example of aggregate sample analysis is the milk ring test for Brucella antibody (Figure 4), which is used for a cost-effective surveillance of dairy herds for brucellosis in areas that have achieved a disease-free status. Often, calculations of the impact of dilution on the sensitivity of aggregate sample analysis are difficult to carry out if the number of animals contributing to the sample is not known.

Aggregate sample analysis of tank milk is currently in use by some farms in New Zealand to isolate S. aureus and generate farm

Activity 5: Advantages and disadvantages of each approach

Reflect on the relative strengths and weaknesses of individual animal specimen, multiple specimen, pooled specimen and aggregate sample analysis, and complete Table 2.

| Type of specimen | Relative strengths | Relative weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Individual specimen | ||

| Multiple specimen | ||

| Pooled specimen | ||

| Aggregate sample |

Answer

| Type of specimen | Relative strengths | Relative weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Individual specimen | Identifies the presence of a pathogen in an animal; agent not diluted | Test result is negative if agent is not present in the specimen or is present below the LoD |

| Multiple specimen | Always increases farm-level testing regime sensitivity | High cost |

| Pooled specimen | May increase farm level testing regime sensitivity. Enables cost effective analysis for multiple pathogens | Pathogen may be diluted below culture LoD |

| Aggregate sample | Avoids expensive sampling activities | Agent’s dilution factor unknown |

4 Bacterial isolation

4.1 Different specimens require different treatments

Specimens received by the microbiology laboratory must be inoculated without delay into an appropriate bacteriological medium. This allows optimal growth of the bacteria present in the specimen and ultimately obtaining a ‘clinical isolate’, which is a pure culture of the presumed pathogen. Methods for inoculation into primary media differ between fluid and solid specimens.

Fluid and semi-fluid specimens are taken directly from the specimen and inoculated into liquid growth medium or spread on the surface of solid medium using bacteriological loops or pipetting.

In the case of solid specimens, it is necessary to inoculate core material taken from below the surface of the specimen. Why is this?

Answer

Core material taken from solid specimens is used to avoid introducing into the media contaminants present on the specimen’s surface.

A common method of dealing with solid specimens consists of:

- an initial sterilisation of the specimen’s surface by searing it with a hot spatula

- an incision of the seared surface using a sterile scalpel to expose the core of the specimen

- extraction of material from the core and transfer to the primary media using a bacteriological loop or a Pasteur pipette.

For small specimens (for example, an avian spleen), the external surface can be sterilised by passing it through a Bunsen flame several times and then cutting it with sterile tools to expose the core. The whole or part of the specimen is then inoculated into the media. The surface of very small specimens is difficult to sterilise and the laboratory depends upon strict aseptic specimen collection techniques. This highlights the need to submit large pieces of tissue.

4.2 Types of media

The choice of media and incubation conditions are guided by the specific requests in the submission form and the type of organisms expected, depending on the range of pathogens circulating in the region.

Bacteriological media are classified according to physical state (Figure 5) and nutrient characteristics.

Liquid media (broths) provide a fertile environment for the amplification of the bacteria present in the specimen, and are usually used to ‘enrich’ the target organism so that it surpasses the LoD of culture.

What are the potential disadvantages of using a liquid rather than a solid medium as the primary growth medium?

Answer

The disadvantages are:

- Unlike on solid media, no discrete bacterial colonies are formed, so it is not possible to obtain individual colonies for testing. This may present difficulties if there is a mixed infection.

- The relative abundance of the bacterial species initially present changes during culture and, in the case of a mixed flora, the target organism might be overgrown by a faster competitor.

All bacteriological media contain a balanced blend of energy sources and micro and macronutrients necessary for in vitro bacterial growth. Supplements may be added to encourage or suppress the growth of particular microorganisms, or to help identify potential pathogens. Table 3 describes the main media types used in microbiology laboratories.

| Media | Characteristics/example | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Basic | Contain a balanced mix of nutrients to support bacterial growth. Example: nutrient agar/broth | For |

| Enriched | Supplemented with extra nutrients (blood, serum, vitamins etc). Example: blood agar | For |

| Selective | Contain substances (antibiotics, salts, dyes) which suppress certain organisms while favouring the growth of others. Example: Mannitol Salt agar used to recover Staphylococcus aureus from Selective broths are often called ‘selective enrichment’ broths, as they enrich the target organism while inhibiting others. |

For non-sterile specimens where competing |

| Differential | Contain a substance, such as a pH indicator, that changes colour in response to bacterial activity, for example, when carbohydrate fermentation leads to acid production by certain organisms. Differential media are sometimes referred to as indicator media. | For basic differentiation of target organisms from other organisms potentially present in the inoculum. |

| Selective-differential | Combine the properties of selective and differential media. Example: MacConkey agar – see Figure 6. Also referred to as selective-indicator media. | To select for and differentiate target organisms from others. |

4.2.1 Storage or preservation media

Storage, or preservation, media are used for storing viable bacterial isolates for long periods. This is necessary to enable further analyses, for example antimicrobial susceptibility testing for surveillance.

What property is required of a good storage medium?

Answer

One important property is the ability to retain moisture, particularly if the sample is to be stored at room temperature. Hence, storage media are often provided in slants (see Figure 5), rather than plates, as slants have a reduced air-to-surface interface compared with plates.

Once inoculated onto an appropriate storage medium, the isolates are kept at the correct temperature according to future use (see Section 6).

4.2.2 Transport media

Transport media are designed to preserve bacterial viability during transport, without allowing their multiplication. They contain buffers, carbohydrates and other nutrients that maintain a stable bacterial composition from the time of specimen collection to its processing in the laboratory.

4.2.3 Activity 6: Culture media in your workplace

Activity 6: Culture media in your workplace

Complete Table 4 based on the types of media you use in your laboratory. What considerations guide your laboratory’s choice of media?

| Name of medium | Use | Category |

|---|---|---|

Discussion

You may use other media not shown in the table.

The media available to your laboratory will depend on factors such as local suppliers, transport and logistics, preferences in your country/region, and cost.

There may be more up-to-date media than the ones you are using. Ready-made media save time in pouring, sterilising and quality control (QC).

| Name of medium | Use | Category |

|---|---|---|

| MacConkey | To select for Gram-negatives and differentiate lactose fermenters from non-lactose fermenters | Solid selective differential |

| Blood agar | Enriched with 5% whole blood. For fastidious organisms. Is also differential by the |

Solid enriched differential |

| Tetrathionate broth | Primary selective broth used for Salmonella | Broth, selective |

4.3 Incubation of bacterial cultures

The incubation of primary cultures has one aim: to obtain a bacterial growth resulting in a visible bacterial population.

Some species will grow better than others, and some will not grow at all. Incubation conditions are used so that they best support the growth of:

- the target bacteria

- a range of other bacteria present in the specimen.

The main parameters are atmosphere, temperature and duration of incubation.

Parallel culture with different sets of media, sometimes incubated under different conditions, is used when the target bacteria have different growth requirements. This has a significant increase in workload and costs.

4.3.1 Incubation atmosphere

Clinically relevant bacteria may be classified based on their atmospheric requirement into:

Anaerobic bacteria vary widely in their tolerance to atmospheric oxygen. For example, Bacteroides and Clostridium species are

Animal health laboratories incubate most specimens in aerobic and/or microaerophilic atmospheres, enabling the growth of aerobes, facultative aerobes and some

Culture for obligate anaerobes requires strict specimen collection and transport techniques to prevent the exposure of the bacteria to the damaging effect of atmospheric oxygen during transport. In many animal health diagnostic laboratories, anaerobic culture is carried out only upon specific request. The identification of obligate anaerobes requires expertise and tests not widely available at regional laboratories, so many anaerobic infections in farm animals are routinely diagnosed using culture-free methods or not diagnosed at all (see Section 5.4.4).

4.3.2 Incubation temperature

Most animal pathogens are mesophiles with optimal growth at of 30–37°C (range: 20–45°C). For this reason, laboratories routinely incubate media at approximately the normal body temperature, between 35 and 37°C.

Lower or higher incubation temperatures are used to target specific organisms. For instance:

- incubation at 4°C may be used for the ‘cold’ enrichment of

psychrophilic species such as Yersinia enterocolitica/Y. pseudotuberculosis and Listeria monocytogenes - incubation at 42°C for the selective enrichment of thermophilic Campylobacter species such as C. jejuni.

Should simultaneous incubation at different temperatures be required, the use of separate incubators is necessary.

4.3.3 Duration of incubation

In the diagnostic setting, the incubation period is the time elapsing between the inoculation of the media and the planned visual inspection of the bacterial growth.

How does bacterial growth appear in liquid and on solid media?

Answer

In liquid media, the growth may appear as a turbid (cloudy) medium, as a sediment on the bottom of the tube or a meniscus on the surface, with a colour change if a chemical growth indicator is present.

On solid media, the bacterial growth appears as a confluent growth or as discrete colonies along the inoculated areas (Figure 8).

The time of inspection varies depending on the expected bacterial species and the bacterial load in the inoculum. Fast-growing bacteria such as Escherichia coli double in number every 10–20 minutes and require short incubations to reach a visible growth, while slow-growing organisms such as pathogenic mycobacteria have a

Long incubation times increase the likelihood of growth of contaminants such as environmental bacteria, and other organisms that require prolonged incubation times.

4.4 Procedures for bacterial isolation

The process of bacterial isolation starts with the arrival of the specimen and concludes with obtaining the ‘clinical isolate’: a pure culture or suspension of the bacterium presumed to be the cause of the infection.

Most laboratories, including animal health laboratories, offer culture routines which target clinically or economically important organisms relevant for the region. Animal health laboratories will generally only look for and identify bacteria relevant for the animal from which the sample has been taken and endemic for the particular country.

Laboratories establish their own routine culture procedures based on various considerations, including the:

- pathogens common in the region

- number and types of specimens received

- availability of technical personnel, supply and equipment

- cost-effectiveness of culture compared with other tests.

Cultures for uncommon organisms, or organisms with complex nutritional requirements (for example, strict anaerobes, rickettsial pathogens, mycobacteria, mycoplasmas) are often not offered (non-culture-based methods may be offered instead), or are only offered by reference or specialist laboratories.

4.4.1 Routine procedures

Animal health laboratories implement highly streamlined microbiological workflows, which should adhere to the laboratory’s SOPs. Individualised analyses are only carried out in specific circumstances, such as during investigations of severe disease outbreaks.

Activity 7: Who decides what procedures to undertake?

What happens in your laboratory when a specimen arrives? Who deals with the specimen first and what actions do they take?

Write in the text box and then compare your notes with the sample answer.

Discussion

Your laboratory may operate differently, but usually a qualified staff member – ideally a veterinary microbiologist – examines the submission form to determine the most appropriate tests for the case based on the clinical information provided.

Any major discrepancy between the microbiologist’s understanding of the case and the tests requested is clarified with the submitting professional at this stage.

The main phases of bacterial isolation are illustrated in Figure 9. The process involves one to three incubation periods, depending on whether a short or long protocol is followed.

Which pathway is best suited for specimens taken from sterile sites, and why?

Answer

The short pathway (blue arrows) is usually used for sterile-site specimens (for example, from pneumonia lung lesions), as direct inoculation on a primary solid medium is likely to yield a

The long pathway (red arrows) is often used for the analysis of non-sterile site specimens where commensals or contaminants are present (for example, faeces), or when an enrichment of a sub-lethally injured pathogen, or a pathogen that may be present below the LoD is needed (for example, specimens collected from an animal treated with antimicrobials).

What is the purpose of the additional sub-culturing step? (See Section 4.2)

Answer

Initial growth in a selective broth enables the growth of the target organism and suppresses the growth of other bacteria present in the inoculum. This allows you to obtain visible colonies of the target organism on the secondary solid medium.

As you will learn in Section 7.3, isolation procedures for Salmonella often combine the two pathways to increase overall testing sensitivity. If salmonellosis is suspected, visceral organs can be cultured on solid primary media and selective enrichment, and faeces in selective enrichment only.

5 Bacterial identification

Bacterial identification is the stepwise process by which a clinical isolate is assigned to a

5.1 Using multiple phenotypic tests to identify the taxon

Experienced bacteriologists can often tentatively identify bacteria on the primary medium based on the type of specimen from which it originated, the colony size, colour and even smell. These traits, along with the

However, most commonly the identification requires obtaining a clinical isolate, as no identification method works on a mixture. Many bacterial groups comprise species with overlapping phenotypes, requiring multiple tests for the identification of the isolate’s species. By selecting the most parsimonious set of differential tests needed for identification, microbiologists can help to make significant savings in both labour and reagents.

Activity 8: Making savings

Let us hypothesise that Streptococcus agalactiae, S. dysgalactiae and S. uberis account for 99% of all streptococcal infections in veterinary practice and infections caused by other streptococci are extremely rare. The laboratory manager wants to implement a cost-effective testing scheme to identify these three streptococci to species level.

Which test is the least useful to distinguish between the three species, and why is this?

Answer

The lactose fermentation test does not differentiate between these species and is the least useful.

- Is there any value/advantage in including the lactose fermentation test in the identification panel?

Answer

The lactose fermentation test may still be useful for differentiation from other streptococci, but we said that the latter are extremely rare. Moreover, the added value of this test for the identification of rarely occurring species will probably be offset by the false negative and false positive results that will inevitably occur. This shows you the limitations of phenotypic testing for bacterial identification, and why you should use the smallest set of tests that offer the best discrimination in your own area. When you add a test, you also add a certain amount of error associated with it that must be accounted for.

5.2 Identification to genus and species level

If the identification of a pathogen’s species requires costly or time-consuming testing schemes or expertise only available in specialised laboratories, the identification may be limited to the genus level. For example, animal diagnostic laboratories often report ‘Salmonella spp.’ (i.e. genus-level), and sometimes the serogroup (for example, ‘Group D’ Salmonella). The identification of Salmonella to species and serovar levels is often performed at reference laboratories.

The professional requesting the tests is responsible for the interpretation of the bacteriological results. For instance, a laboratory report of the isolation of a coagulase-positive Staphylococcus from a case of bovine mastitis is usually interpreted as an infection with the species S. aureus, as non-aureus coagulase-positive staphylococci are extremely uncommon in cows.

Lastly, some bacterial groups include species with broadly overlapping phenotypes, making it difficult to distinguish between them using phenotypic keys. In these cases, the species could be defined using genetic markers or advanced techniques, as you will learn in Sections 7.4–7.5.

5.3 Commercially sourced manual phenotypic tests

Many phenotypic tests used for bacterial identification are done manually and require sterile media and glassware. Commercial self-contained kits containing arrays of miniaturised biochemical tests are designed to replace these traditional test-tube biochemical tests.

What are the general disadvantages of commercial phenotypic tests?

Answer

Limited shelf life and relatively high cost.

Activity 9: Exploring common commercial tests

Part 2 (Optional):

If you have access to the Internet and wish to explore commercial testing kits further, click on each test listed below to access the information.

- API®

- Bacterial Biochemical Identification Kits by Creative Diagnostics®

5.4 Other commercially sourced technologies

This section introduces a range of technologies for bacterial identification, not all yet in common use in animal health laboratories.

5.4.1 Automated systems

Automated systems such as Vitek II (Biomerieux), BD Phoenix (Beckton Dickinson) and Beckman-Coulter-MicroScan are used in large human clinical laboratories.

Effectively, these are automated versions of the biochemical test kits, with more reagents, automated reading of results and analytic software so that technician interpretation is not required.

The cost of these systems is high, but they require less work than traditional tests. Another advantage is that

5.4.2 Rapid methods

Traditional bacterial identification techniques rely on long incubations. Rapid, culture-free techniques that employ fluorescence, light scattering or other techniques to detect bacteria before their colonies can be seen by the naked eye are used by some large human laboratories.

5.4.3 MALDI-TOF MS

Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time Of Flight mass spectrometry (

The MALDI-TOF MS ‘fingerprints’ the isolate’s

Can you think of any potential disadvantages of using MALDI-TOF MS to identify animal pathogens?

Answer

The main disadvantage, common to both human and animal health laboratories, is the high cost of the instruments and ongoing service contracts. However, where sample throughput is very high, this may be off-set by savings in reagent and work-force costs. As the caseloads of many animal health laboratories is not very high, these laboratories may need to submit the isolates to external service providers.

Another perceived problem is the lack of comprehensive proteome databases for animal pathogens. However, this knowledge gap is being filled quickly.

If you are unfamiliar with MALDI-TOF, watch the short video below describing it.

5.4.4 PCR-based bacterial identification

As you learned in Section 5.2, bacterial genera may comprise species that share overlapping phenotypes, and it may be necessary to apply PCR-based

Two main PCR-based genotyping strategies are used for species identification:

- Sequence analysis of 16S rRNA (16S ribosomal RNA) gene regions is often used for bacterial species identification as this gene regularly displays greater variation between than within species. Hence, comparative analysis of 16S rRNA sequence data may allow the identification of the species where phenotypic tests alone fail to do so.

- PCR amplification of species-specific gene fragments. Many bacterial species contain genes that are not present in the

genomes of related bacteria. Detection of such genes can be used to confirm or rule out a species. Identification of some Campylobacter species, and even S. aureus can be achieved using this method.

5.4.5 Whole genome sequencing (WGS)

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is a method for rapid sequencing of the chromosomal DNA and mitochondrial DNA (and chloroplasts DNA in plants). WGS is carried out using next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, which allows the rapid generation of large quantities of genomic data.

WGS has the potential to become an important tool in pathogen surveillance. However, the challenge in AMR is the timely processing of the large volumes of data, particularly during emergency pathogen outbreaks (Bogaerts, 2021 and Jauneikaite, 2023). As a result, the Surveillance and Epidemiology of Drug-resistant Infections Consortium (SEDRIC, n.d.) working group are working on a series of recommendations on the use of genomic surveillance via WGS for AMR. The working group has identified various advantages and barriers to the use of WGS in AMR.

Advantages

Healthcare-associated infections in hospitalised patients pose a significant challenge globally. Genomic AMR surveillance of pathogens using WGS from healthcare-associated infections can provide much better identification of the causative agent, such as genomic subtypes. It can also help to identify facility-level trends.

One particular advantage of WGS is its use to investigate outbreaks and to improve support for infection prevention and control in AMR surveillance in healthcare facilities. It can help to identify complex epidemiological patterns, such as the emergence of new strains and expansion of new multidrug-resistant strains.

Barriers

Despite many advantages, there are still many barriers to WGS in AMR surveillance. The initial set-up and running costs can be prohibitive, or the equipment difficult to obtain due to poor distribution networks and supply chains.

There are also significant challenges in the analysis and interpretation of the genomic data, which typically requires bioinformaticians. Quality assurance processes for both laboratory sequencing and bioinformatic analysis have yet to be clearly defined.

The course Whole genome sequencing in AMR surveillance discusses WGS in more detail.

6 Preservation of isolates

Although bacteria may remain viable on the isolation plates for several days, longer-term viability of isolates requires either inoculation onto storage/preservation media (see Section 4.2.1) or an alternative preservation method. The choice of method largely depends on the experimental purpose and the availability of specific equipment and deep freezers.

The length of time that an isolate will remain viable depends on the bacterial species in question. A certain level of cell death during storage is inevitable, but it can be minimised. As a rule, the lower the storage temperature, the longer the viable period.

Activity 10: Storing isolates

Reflect on the reasons to store isolates in your laboratory.

Discussion

Reference strains for QC (including for AST) are stored in most laboratories. Laboratories may also store isolates of Salmonella and other notifiable agents and periodically submit batches to reference laboratories for typing. Laboratories may also need to participate in surveillance or research programs where their isolates are re-tested in other laboratories.

6.1 At room temperature or in refrigeration

Isolates used daily or weekly (for example, control strains) can be preserved in refrigeration at 2–4°C. It is hard to put a time limit, but Salmonella and S. aureus might remain viable for up to 2–3 months in refrigeration and for shorter terms at room temperature.

The isolates to be stored are grown on an appropriate solid storage medium slant to reduce desiccation. Strict aseptic techniques during subculture and manipulations of the isolate are important to prevent bacterial and fungal contamination.

Frozen or freeze-dried ‘copies’ (see Sections 6.2–6.3) that can be resuscitated when needed, should be prepared and kept in reserve.

A final consideration concerns successive subcultures. These should be kept to a minimum due to the risk of mutations and phenotypic changes. For example, when repeatedly passaged in the laboratory, some strains may lose plasmids harbouring antibiotic resistance genes.

6.2 By freezing

Freezing damages bacterial cells due to the localised increase in salt concentration and the damage to cell membranes caused by the forming of ice crystals. Despite this, most bacteria survive well.

Key factors to successful bacterial freezing are:

- a large initial cell density of at least 107 CFU per mL

- using

cryoprotectants for freezing (e.g. glycerol; DMSO) - ‘snap freezing’.

Reductions in bacterial viability occur during the initial freezing and each time the bacteria are thawed. Thus, the greater the initial cell density and the more protected the cells, the better the isolate’s survivability. Efficient bacterial freezing kits are also available on the market.

It is a good idea to preserve each isolate in several screw-cap cryogenic vials so that the same sample is not taken out of the freezer each time the isolate is required. It is not necessary to thaw the whole vial each time the isolate is needed – the frozen surface can be scraped to obtain a small amount of bacteria.

Snap freezing in dry ice or liquid nitrogen limits cell damage. The frozen bacteria can then be stored between ‑20°C and -80°C, or in liquid nitrogen at -150°C. If snap freezing is not possible, it is acceptable to put unfrozen bacteria directly into -70°C or -80°C or into liquid nitrogen. Direct storage at -20°C is not recommended as it is likely to drastically reduce viability.

6.3 By freeze-drying

Bacteria can be freeze-dried in central laboratories by suspending them in a

What are the disadvantages of freeze-drying?

Answer

- Successful bacterial freeze-drying requires expertise and quite expensive equipment.

- Not all bacteria can be freeze-dried.

7 Isolation and identification of key pathogens of interest in terrestrial farmed animals

In this section, we focus on key animal pathogens and their identification.

7.1 Organisms of interest

This course focuses on three common animal pathogens included in the list of thirteen priority bacterial pathogens for surveillance of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS), and on two bacterial genera widely used in the monitoring of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in farm animals (Table 6). Information about the GLASS programme can be found in the Introducing AMR surveillance systems course.

| Animal pathogen | Notes | |

|---|---|---|

| GLASS pathogens | Escherichia coli | Common in poultry and livestock |

| Salmonella species | Common in all production animals | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Common in poultry, farmed ruminants and pigs | |

| Used for AMR monitoring | Enterococcus species particularly E. faecium and E. faecalis | Causes infections in humans and resistance is a particular problem Can cause sporadic infections in farm animals |

| Campylobacter spp. | An important cause of human gastroenteritis which may result in antimicrobial use, especially C. jejuni and C. coli C. fetus subsp. fetus and C. fetus subspecies venerealis cause infections in sheep and cattle |

7.2 Escherichia coli

What are the main characteristics of E. coli?

Answer

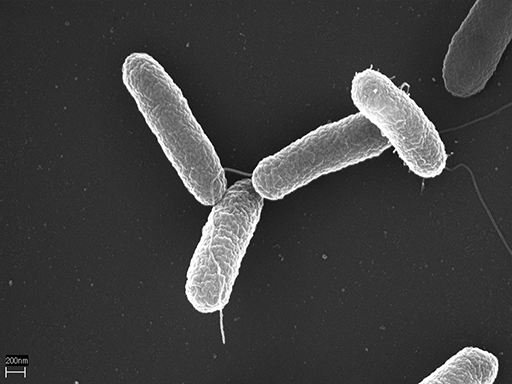

E. coli is a Gram-negative, oxidase-negative, facultative anaerobic Enterobacterales.

E. coli live as commensals of the large intestine of humans and animals, and low virulence strains may cause a range of sporadic

In farmed animals, E. coli is associated with specific endemic diseases of significant economic impact, such as:

- Entero-toxigenic E. coli diarrhoea in newborn calves and piglets

- E. coli oedema disease in piglets

- Bovine mastitis

- Colibacillosis of poultry.

7.2.1 Isolation of E. coli

Is the isolation of E. coli from a faecal specimen a diagnostic confirmation of an infection?

Answer

It depends. Unlike Salmonella, E. coli are usually harmless intestinal commensals. Their isolation from faeces is trivial, but it has a diagnostic value if followed by the identification of specific virulence factors, such as the K99 factor in an E. coli isolated from a calf with diarrhoea.

Is the isolation of E. coli from a sterile site specimen indicative of an infection?

Answer

Recovery of these bacteria in pure culture from sterile site specimens is suggestive of an infection, although agonic and post-mortem invasion should also be considered.

A common isolation and identification protocol for E. coli from sterile sites is shown in Figure 11.

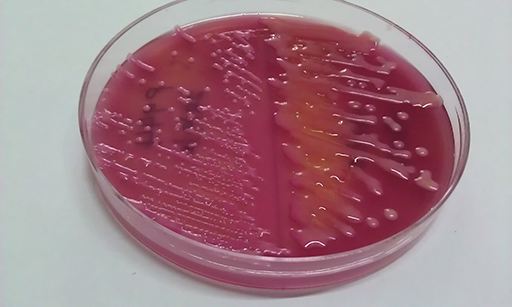

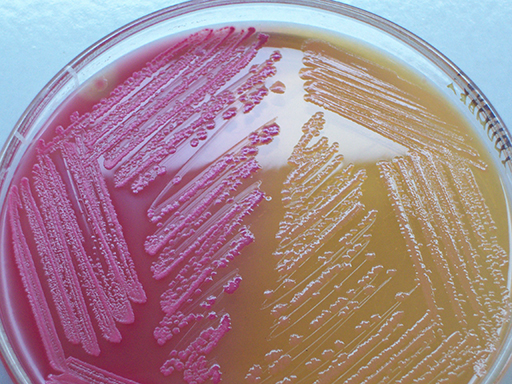

These organisms are normally cultured using solid media. Note that to cover Gram-negatives and Gram-positives, in this scheme specimens are plated in parallel on blood agar and selective-differential MacConkey agar. E. coli is a lactose fermenter, producing red colonies on MacConkey (Figure 12). The isolate is then tested by a panel of biochemical tests for identification.

7.3 Salmonella species

What are the main characteristics of Salmonella?

Answer

Salmonella is a genus of Gram-negative rods with two species: S. enterica, which is divided into six sub-species, and S. bongori. A further level of classification, which is perhaps the most important from a practical standpoint, is the classification into more than 2500 Salmonella ‘

Salmonella is included in the list of priority pathogens for AMR surveillance in humans and animals as some species colonise the intestinal tract of humans and production animals and cause severe human diseases such as typhoid fever (humans) and salmonellosis (humans and animals). In animals, Salmonella strains cause clinical conditions ranging in severity from subclinical carriage to abortions, diarrhoeal disease, septicaemia and death.

Salmonella infections in farm animals are of great concern not only due to the significant impact of salmonellosis on farm economics, but mainly because of the severe consequences direct zoonotic and food-borne transmission have on public health. For these reasons, Salmonella isolation and identification represents a core capacity in animal microbiology diagnostic laboratories worldwide.

7.3.1 Isolation of Salmonella

Salmonella comprise fast-growing facultatively anaerobic species that grow well in basal media such as nutrient agar or nutrient broth.

Activity 11: Isolating Salmonella in your workplace

Think about your workplace activities and consider these questions.

- What types of specimens are commonly submitted for Salmonella culture?

- What types of primary media are used, and why?

Answer

- Faeces and visceral organs are the most common specimen types submitted to diagnostic laboratories for Salmonella culture. Sometimes, feed may be submitted to identify possible feed-borne outbreaks of salmonellosis.

- Basal media are not commonly used as the primary isolation medium for the isolation of Salmonella from faeces, as they will promote the growth of many organisms and the salmonellae will remain undifferentiated.

Clinical specimens obtained from sterile-sites can be inoculated on primary solid selective differential media suitable for Salmonella, such as MacConkey agar,

A common isolation protocol for Salmonella from clinical specimens is shown in Figure 14. Different Salmonella serovars may have different recovery characteristics in selective enrichment media. Therefore, some isolation protocols include two different enrichment broths inoculated in parallel. Note that media are incubated at 35–37°C for 24h in aerobic atmosphere, but some laboratories incubate one broth at 42°C. This provides an additional selection barrier, as many serovars grow well at such a restrictive temperature.

A complete identification scheme for Salmonella spp. requires an agglutination test using an anti-Salmonella polyvalent serum. Further identification would require the definition of the serovar, as different serovars have different

Salmonella isolates can be stored frozen, freeze dried or refrigerated, and may remain viable for several weeks on storage media slants in refrigeration, or even at room temperature.

7.4 Staphylococcus aureus

What are the main characteristics of S. aureus?

Answer

S. aureus belongs to the genus Staphylococcus. It is a Gram-positive, catalase-positive and coagulase-positive aerobic coccus, although the capacity to produce coagulase enzyme may be weak in some strains.

S. aureus is included in the list of priority pathogens for AMR surveillance since many lineages carry genes that confer resistance to virtually all the

MRSA are less problematic in veterinary medicine as infections with such strains are not very prevalent. However, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) strains cause a range of infections in production animal species, including:

- contagious mastitis in farmed ruminants

- sporadic or endemic skin infections in all animals

- sporadic wound, soft tissue and bone infections in all animals

- endemic joint infections in poultry.

Despite some worrisome documented evolutionary host-jumps from livestock to humans, transmission of S. aureus from farm animals to humans is not common and usually, S. aureus is not considered a zoonotic agent. Moreover, comparative genomic analyses of human and animal strains indicate that humans and livestock are generally infected with host-specialised lineages that tend to remain confined within their host-niche.

7.4.1 Isolation of S. aureus

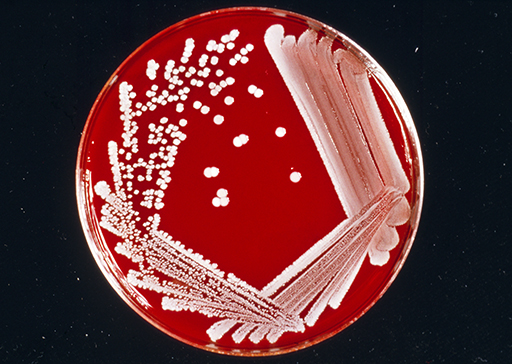

S. aureus is a fast-growing bacterium that grows well in basal medium but is usually cultured on sheep blood agar plates that are more widely used as primary media. Occasionally, clinical specimens from non-sterile sites may need an initial incubation into selective enrichment broth (see Section 4.4.1). This can be achieved in a basal nutrient broth supplemented with 7.5% NaCl (S. aureus is

The characteristic colony appearance, coupled with the Gram-stain reaction and a positive rapid catalase test, allow its tentative identification by the experienced microbiologist (Figure 16). Regardless of whether a preliminary identification is made based on the above, a comprehensive procedure can be used to identify S. aureus (Figure 17).

S. aureus can be stored frozen, freeze dried or refrigerated, and may remain viable for several weeks on storage media slants in refrigeration, or even at room temperature.

7.5 Enterococcus faecium and E. faecalis

What are the main characteristics of E. faecium and E. faecalis?

Answer

E. faecium and E. faecalis are Gram-positive, catalase-negative, facultative anaerobic cocci. There are significant phenotypic overlaps between enterococci and some streptococci, and between various species of enterococci.

The enterococci are part of the normal intestinal flora of humans and animals. E. faecalis and E. faecium are the most common species isolated from human infections and are among the most important causes of

In farm animals, enterococci are sporadically isolated from cases of bovine mastitis, septicaemia and internal organ infections in newborn farmed ruminants and poultry. E. faecium and E. faecalis are associated with MDR and the two species are widely used as indicators of antimicrobial resistance in production animals.

7.5.1 Isolation of E. faecium and E. faecalis

Primary inoculation of blood agar incubated aerobically or in 5–10% CO2 at 35–37°C for 24–48h will support the growth of many species of Enterococcus. Often, however, selective azide blood agar is used to inhibit Gram-negatives.

Activity 12: Isolating E. faecium and E. faecalis in your workplace

Think about your workplace activities and/or reflect on what you have learned so far in the course and consider these questions.

- How could you isolate E. faecium and E. faecalis reliably from clinical specimens and differentiate these organisms from Streptococcus and from other Enterococcus species?

- What characteristic appearance would colonies of these organisms display on blood agar and what further tests might you use to confirm E. faecium and E. faecalis?

Answer

- Selective solid media containing sodium azide for the suppression of the growth of Gram-negatives can be used as primary medium in addition to blood agar.

- Colonies are 1–3 mm in diameter, non-haemolytic or partially-haemolytic. A further catalase test would be negative.

- However, both these features are not specific, and further testing is necessary.

Due to the difficulty in distinguishing enterococci from each other and from streptococci, the identification of E. faecium and E. faecalis is not always straightforward. Most animal diagnostic laboratories therefore apply rudimentary identification routines for the enterococci, probably leading to many false positive and false negative results.

The following differential features enable the identification of the enterococci.

- Enterococcus spp. express

Lancefield group D surface antigen, enabling a differentiation from non-D streptococci. - Many enterococci hydrolyse aesculin in the presence of bile, and grow in the presence of 6.5% NaCl.

- The application of a purposive combination of biochemical and antimicrobial susceptibility tests will enable a correct differentiation between

group D streptococci and Enterococcus spp. in many cases. However, any stringent scheme should include PCR-amplification of Enterococcus genus-specific loci. - The use of commercial chromogenic agar media enable the differentiation between E. faecium and E. faecalis. Further analysis could include specific antimicrobial resistance tests and other phenotypic tests, or sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene.

Enterococci can be stored frozen, freeze dried or refrigerated, and may remain viable for several weeks on storage media slants in refrigeration, or even at room temperature.

7.6 Campylobacter species

What are the main characteristics of Campylobacter?

Answer

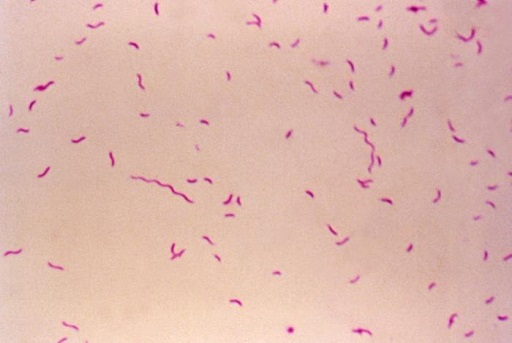

Campylobacter are Gram-negative, oxidase-positive microaerophilic bacteria requiring incubation at atmospheres enriched with 3–5% CO2. Some species, for example, Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli, are thermophilic and grow well at 42°C.

Many species of Campylobacter are commensals of the intestinal tract of birds and mammals. C. jejuni and C. coli are among the most frequently reported bacterial causes of human gastroenteritis globally, but in farm animals these organisms remain harmless, except C. jejuni, that was found to be a cause of abortion in sheep.

Disease-causing Campylobacter species in animals include:

- C. fetus subspecies fetus: an important cause of abortions in cows and sheep.

- C. fetus subspecies venerealis: a venereally transmitted organism causing bovine genital campylobacteriosis, a subclinical infection of bulls that causes early abortion and infertility in cows.

- C. hepaticus: recently associated with acute necrotic hepatitis in laying hens.

7.6.1 Isolation of Campylobacter species

All Campylobacter species are fastidious and relatively slow growers, and small colonies are evident on enriched media after 48–72h of incubation. There are many established protocols for the isolation and identification of C. jejuni and C. coli from animal faeces for surveillance and research purposes.

Diagnosis of C. fetus subspecies fetus relies on the isolation of the bacterium from fetal stomach, liver, lungs, or placental cotyledons. Sterile site lung and stomach specimens from aborted fetuses can be plated directly on blood agar plates and incubated in 3–5% CO2 for up to five days. Contaminated specimens will require inoculation onto selective media containing antibiotics, but such media may also inhibit the growth of many C. fetus strains.

C. fetus subspecies venerealis is more fastidious, with low recovery rates of culture reported worldwide. Hence, diagnosis of bovine genital campylobacteriosis is often done using PCR or other culture-free methods (see Section 5.4.4).

Genus identification is done phenotypically by assessing colony morphology, and the presence of typical gull-shaped, oxidase-positive, Gram-negative bacteria (Figure 20). Biochemical reactions allow a presumptive species identification. If needed, species-specific PCR or 16S rRNA gene sequencing can be done for species confirmation.

Campylobacter can be stored frozen or freeze dried, but viability drops significantly when stored at room temperature or refrigerated.

8 Fundamentals of quality control for isolating and identifying bacteria

In a veterinary microbiology laboratory, several factors can affect the accuracy and reliability of test results. Quality control (QC) measures are therefore put in place to monitor whether tests perform as expected and do so reliably. You will learn more about QC and other

Activity 13: QC in veterinary microbiology laboratories

Based on your work experience and on what you have learned in this course, why do you think QC is important when identifying pathogens from clinical specimens?

Discussion

QC ensures the following:

- Media fertility: you can actually grow the organisms you’re looking for.

- Media sterility: your media do not contain viable contaminating bacteria that can grow during incubation.

- Your media and test reagents are working correctly, for example, if they have deteriorated during storage or there is something wrong with what the manufacturer has supplied, the QC tests will pick this up.

- You are performing the tests under optimal conditions, for example, the incubator is at the right temperature.

- Your tests are repeatable: each time you use the same strain, you get the same result.

9 Identifying pathogens in your workplace

You should now have a better understanding of the microbiology techniques used in a veterinary microbiology laboratory for isolating and identifying pathogenic bacteria of particular interest for diagnosis and/or AMR surveillance. Before you finish the course, complete this final activity, which will help you think about your laboratory’s diagnostic capacity.

Activity 14: Identifying pathogens in your workplace

Think about the six types of pathogen of interest in farm animals and reflect and make notes in response to the following questions.

- Are you identifying all of these pathogens to the required level in your laboratory?

- Are you confident that the identification is accurate?

- Are there areas where you feel your laboratory may not be reliably identifying pathogens? Which pathogen(s) does this apply to?

- How could the diagnostic capacity of your laboratory be improved and what are the barriers to achieving this? For example, what extra equipment and reagents might you need? Are the correct controls being used? Do staff need more training?

Finally, think about how you would make a case to your Laboratory Manager to convince them to support you in improving your laboratory’s diagnostic capacity.

Discussion

You may find it helpful to discuss your thoughts with colleagues before talking to your Laboratory Manager.

You may also wish to return to this activity when you have completed the Quality assurance and AMR surveillance course.

10 End-of-course quiz

Well done – you have reached the end of this course and can now do the quiz to test your learning.

This quiz is an opportunity for you to reflect on what you have learned rather than a test, and you can revisit it as many times as you like.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window by holding down ‘Ctrl’ (or ‘Cmd’ on a Mac) when you click on the link.

11 Summary

In this course, you have learned about the principles of bacterial isolation and identification in the veterinary clinical setting, with reference to production animal medicine. Some of these tests are routinely performed in veterinary microbiology laboratories, while other techniques are used only in reference laboratories. You have also been introduced to factors related to specimen collection, quality and handling which can positively or negatively impact testing.

You should now be able to:

- rationalise specimen collection protocols with the aim of improving the effectiveness of the bacteriology diagnostic laboratory

- evaluate how different types of specimens, and their quality and condition, may impact the performance of microbiological tests

- describe the principles of laboratory tests used to isolate and identify the bacterial pathogens on which this course focuses

- critically analyse microbiological methods used by front-line veterinary diagnostic laboratories

- know when, why and how advanced testing (e.g. by mass spectrometry, automated systems and DNA-based tests) are used

- reflect on the importance of procedures designed to ensure the quality of laboratory work relating to isolating and identifying bacteria.

Now that you have completed this course, consider the following questions:

- What is the single most important lesson that you have taken away from this course?

- How relevant is it to your work?

- Can you suggest ways in which this new knowledge can benefit your practice?

When you have reflected on these, go to your reflective blog and note down your thoughts.

Activity 15: Reflecting on your progress

Do you remember at the beginning of this course you were asked to take a moment to think about these learning outcomes and how confident you felt about your knowledge and skills in these areas? Now that you have almost completed this course, take some time to reflect on your progress and use the interactive tool to rate your confidence in these areas using the following 1–5 scale.

- 5 Very confident

- 4 Confident

- 3 Somewhat confident

- 2 Slightly confident

- 1 Not at all confident

Try to use the full range of ratings shown above to rate yourself.

Reflect on your progress by comparing your answers here to those you wrote at the beginning of the course. Have your responses changed?

When you have reflected on your answers and your progress on this course, go to your reflective blog and note down your thoughts.

12 Your experience of this course

You’ve now reached the end of this course. If you’ve enrolled on a pathway, please go back to the pathway page and tick the box to confirm that you’ve completed this course. On the pathway page you’ll see both your progress so far as well as the other courses you need to complete in order to achieve your Certificate of Completion for that pathway.

Now that you have completed this course, take a few moments to reflect on your experience of working through it. Please complete a survey to tell us about your reflections. Your responses will allow us to gauge how useful you have found this course and how effectively you have engaged with the content. We will also use your feedback on this pathway to better inform the design of future online experiences for our learners.

Many thanks for your help.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Alex Grinberg and Sarah Palmer and reviewed by Liz Sheridan. The course was reviewed and updated by Maria Garza Valles,Vikki Haley and Rachel McMullan in 2025.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Course image: Andriy Popov / Alamy Stock Photo

Figure 2: Westpoint Farm Vets

Figure 3: Rainard, P., et al. (2018) Host factors determine the evolution of infection with Staphylococcus aureus to gangrenous mastitis in goats, Veterinary Research, 49, 72, https://doi.org/ 10.1186/ s13567-018-0564-4 This file is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license, https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by/ 4.0/

Figure 4: Taken from Srinu, B., Anumolu, Vijaya kumar & Kumar, M & Narayana, B.V.L. & Rao, T. (2012) Assessment of Microbiological quality and associated health risks of raw milk sold in and around Hyderabad city, International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences ISSN 0975-6299, Oct; 3(4): (B) 609 – 614

Figure 5: Adapted from itsfareedtareen, 'Culture Media Preparation', Quizlet, https://quizlet.com/ 132061981/ 9-culture-media-preparation-flash-cards/

Figure 6: Medimicro, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/ File:MacConkey_agar_with_LF_and_LF_colonies.jpg

Figure 7 (top): Don Whitley Scientific

Figure 7 (bottom): Taken from Taha, M. (2013) Microbiology Practical Invaders, https://www.slideshare.net/ MohamedTaha16/ invaders-09-102012

Figure 8 (top): Science Prof Online (SPO), www.scienceprofonline.com

Figure 8 (bottom): JOHN DURHAM / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Figure 9: From G. R. Carter, Diagnostic Procedures in Veterinary Bacteriology and Mycology, 3rd Edition, 1979. Courtesy of Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd., Springfield, Illinois

Figure 10: DAVID MCCARTHY / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Figure 12: Microrao, 'E.coli vs K.pneumoniae', https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/ File:E.coli_vs_K.pneumoniae.jpg This file is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license, https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 4.0/ deed.en

Figure 13: Volker Brinkmann, Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin, Germany in 'A Novel Data-Mining Approach Systematically Links Genes to Traits' (2005) PLOS Biology 3(5): e166. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/ journal.pbio.0030166 This file is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic (CC BY 2.5) license, https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by/ 2.5/

Figure 15: National Institutes of Health / Stocktrek Images / Getty Images

Figure 16: Rich Davis, PhD, D(ABMM), MLS, @richdavisphd, https://twitter.com/ richdavisphd/ status/ 1369813213555003393?lang=ar

Figure 18: EYE OF SCIENCE / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Figure 19: DENNIS KUNKEL MICROSCOPY / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Figure 20: Public domain image sourced from: CDC, https://phil.cdc.gov/ Details.aspx?pid=6657