Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 22 January 2026, 5:51 AM

Health Management, Ethics and Research Module: 10. General Principles of Health Research and Introduction to Community Surveys

Study Session 10 General Principles of Health Research and Introduction to Community Surveys

Introduction

One of the very first tasks that you will do as a Health Extension Practitioner when you are deployed to a kebele is to find out everything you can about the people in your community and the factors that influence their health. This information is vitally important because the services you provide must be targeted to meet the community’s needs. The way you begin to find out this information is to conduct a community survey, which is a specific type of health research. The purpose of the survey is to generate data to help you construct a community profile – a report on the households in the community, their inhabitants and their health needs and problems. Your knowledge of what data to collect, how to collect it and how to make sense of your findings by analysing and interpreting the data, will be covered in detail in Study Sessions 11 to 15.

However, before you can conduct your community survey, you need to understand the general principles of health research, which apply not only to community surveys, but to other types of health research which you may wish to undertake in the future. This study session will introduce you to those principles and prepare you for later study sessions. You may be asking yourself why it is necessary for you to learn about health research. You can think of health research as a problem solving tool, to focus your efforts on health interventions in areas that will be of most benefit to your community. In order to know what these interventions are, you require accurate information on community health needs, and reliable knowledge about the possible consequences of any actions you take to address those needs. The community survey is the most important form of health research that you will undertake, but you may also be able to conduct some small-scale health research projects to investigate specific health issues in your community. This study session will help to prepare you for these possibilities.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 10

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

10.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 10.1, 10.2, 10.3 and 10.4)

10.2 Describe the general principles and purposes of health research, distinguishing between basic and applied, quantitative and qualitative, and cross-sectional and longitudinal health research. (SAQs 101, 10.2 and 10.4)

10.3 Describe the types of data collected in national censuses, large-scale surveys and local community surveys, and the common methods and questions used to collect survey data. (SAQs 10.3 and 10.4)

10.1 What is health research?

Research is the collection, analysis and interpretation of data with the aim of answering certain questions or solving certain problems. Health research is aimed at investigating health-related problems systematically and using this knowledge to design better solutions for these problems. It is concerned with improving the health of people and communities by improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the health system, and supporting the community’s own ability to take actions that preserve and protect the health of community members.

When we say that research has to be systematic, this means that a clear ‘system’ is used for collecting, recording, analysing and interpreting all the data, that the system does not change during the research, and that everyone involved handles the data in exactly the same way.

The focus of health research that will be of most interest to you as a Health Extension Practitioner includes:

- The health needs in your community, including for health promoting services such as family planning and antenatal care (Figure 10.1).

- Resources necessary to provide the essential health services that your community needs.

- The effective organisation and management of the health services you provide.

- The monitoring and evaluation of your health education initiatives and health service provision in terms of their outcomes and impact on community health.

10.1.1 Guidelines for health research

The essential guidelines for every health research study (including your community survey) are listed below.

- Research should focus on priority health problems in the community, and there should be a clear statement of the problems.

- A research study needs clear objectives and a plan; it should not be aimlessly looking for something in the hope that you will come across a solution.

- The research plan should be action-oriented, i.e. aimed at discovering solutions for a priority health problem.

- It should be participatory in nature, involving all stakeholders (see Section 10.1.2).

- Simple, short-term research designs that are likely to yield practical results quickly should be used wherever possible.

- The planned research should be cost-effective, i.e. affordable within available budgets and offering good ‘value for money’ in terms of its likely outcomes.

- The researcher(s) should have appropriate expertise in the data collection methods and study design; the work should be carried out systematically and with patience, and should not be hurried.

- The results should be based on observable evidence; observations, descriptions and results should be carefully recorded and accurately reported without any bias.

- The research should be scheduled in such a way that results will be available in time to take the necessary actions recommended by the research findings.

- Results should be presented in formats that are most useful for administrators, decision makers and community members to understand (see Study Session 13).

- The research should be reproducible, so that the same result could be obtained by different investigators if they used the same methods.

10.1.2 Stakeholder participation in health research

Many health-related problems and concerns are interrelated and are influenced by factors in other areas beyond those directly connected to health. For example, health may be affected by problems concerning agriculture, water, roads, environmental factors, poverty and so on. It is better if everyone directly or indirectly concerned with a particular health or healthcare problem is involved in designing and implementing a health research project (including your community survey). The stakeholders may include policymakers, managers from the health and other public services, healthcare providers, and community leaders and members. Their close involvement helps the research findings to be relevant and accepted by all stakeholders, and the resulting solutions are more likely to make a difference to the health problems identified by the research.

Here are some examples of what can go wrong without full stakeholder participation in health research in a community:

- If decision-makers are only involved after a study is completed, the report may just be shelved and the results ignored.

- If the staff of health and other public services are only involved in data collection, but not in the development of the survey or research proposal, or in the analysis and interpretation of the results, they will have less interest in the research and may not be motivated to collect accurate data or carry out the recommendations.

- If community members are only asked to respond to questions determined by the researchers, the recommendations from the study may not be acceptable because the local cultural context, beliefs and wishes have not been taken into account.

- If community members are not involved in the implementation of recommendations, they may have little concern for whether the actions are feasible, affordable or cost-effective.

The roles that various types of participants will play in the health research will depend on its area of focus and also on the level and complexity of the particular study. For example, the health needs in your community may be connected with problems or deficiencies elsewhere, such as agriculture (e.g. whether there has been a good harvest), water (e.g. whether clean drinking water is available, Figure 10.2), roads (e.g. how long it takes to get to the health centre), or broader environmental factors (e.g. how much rain there has been). Health research to identify problems that have a connection to factors outside the health system will require collaboration with all the concerned parties in order to design effective solutions.

In the sections that follow, because of the participatory nature of health research, especially your community survey, we will use the term ‘researcher’ to mean anyone actively involved in planning and conducting the survey or other research – which of course includes you!

10.2 Types of health research

There are different ways of classifying health research. You will learn more about these in Study Session 14, but here we will give a brief outline of some of the key terms and principles.

10.2.1 Basic and applied research

Research can be basic or applied depending on its objectives. Basic (or pure) research is designed to extend knowledge for the sake of understanding itself. The results may not have any applications – discovering new knowledge and understanding is the objective. Applied research is carried out in order to solve specific and practical problems. Applied research is sometimes called action research. Of course, some of the new knowledge obtained through basic research may later be applied to solve practical problems.

Applied health research is mainly intended to improve community health and health services, and add to greater professional effectiveness in a practical manner. Most of the problems faced by healthcare providers, policymakers and administrators are investigated through applied health research. Applied health research emphasises the identification of priority health problems, evaluation of the effectiveness of health programmes and policies, and managing the optimal use of available resources. As you will see later, a community survey is a type of applied health research.

10.2.2 Quantitative and qualitative research

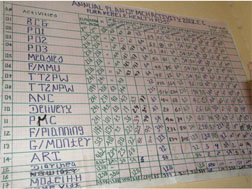

Quantitative research is a type of research that utilises quantitative (numerical) data and seeks answers to questions such as ‘How many?’, ‘How much?’ and ‘How often?’ It involves measurement or counting, for example: ‘What is the average number of people living in households in your kebele?’, ‘How many women are there in the childbearing age groups?’ and ‘What percentage of the children have been fully immunized by the age of one year?’ Quantitative research can be used to describe current situations, to investigate relationships and to study causes and effects. When you conduct your community survey, the majority of the data that you collect will be quantitative data that you can present in tables and charts like the one in Figure 10.3.

Qualitative research is a type of research that utilises qualitative (descriptive) data and seeks answers to questions such as ‘Why?’ and ‘How?’ It is concerned with what people think and how they feel. For example, you might need to know why some parents are not bringing their children for immunizations, or why some pregnant women are reluctant to see you for antenatal care (Figure 10.4). You may need to conduct interviews or focus groups to find the answers, which you will report by writing about your findings.

There is more about the application of qualitative research in Part 2 of the Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation Module.

10.3 An introduction to surveys

A survey is a method of gathering information about a large number of individuals in a population. Surveys can differ in their scale (how many people are questioned), whether the survey occurs once at a single point in time or is repeated again and again, and in the methods used to collect the data. All of these points will be discussed and illustrated in more detail in later study sessions, but it will be easier for you to grasp the details if we first give you a general overview.

10.3.1 Censuses, large-scale surveys and community surveys

A census is a collection of information on everyone in a population – usually everyone in a national population, such as the whole of Ethiopia, or everyone in a national region such as Oromiya or Tigray. Census information is collected in order to gain important data that is relevant to the population as a whole and is ideally collected from every household, although this is not always possible in remote rural areas or where nomadic people are moving from place to place. Large-scale surveys are similar to a census, but the large numbers of people who are questioned are selected to be representative of the population (i.e. not everyone is questioned). In a community survey, the aim is to obtain information about everyone in a local community, usually by questioning an adult member of each household.

The national census, large-scale population surveys and local community surveys all tend to collect demographic and/or epidemiological data. Demographic data are counts of certain social characteristics of a human population: for example, the number of people in a household, their age, gender, ethnic group, whether married, single or divorced, when children were born, etc. – and sometimes also the religion, economic circumstances and other personal characteristics of the population. Epidemiological data refers to counts of diseases, disorders and disabilities in the population, including those leading to deaths. The combination of demographic and epidemiological surveys can shed light on factors that increase the risk of developing particular diseases, or dying from certain causes. The data can be collected at the national level in a census or large-scale survey, or at the local level in a community survey.

An example of a large-scale national survey is the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), which is a nationally representative household survey that collects data on health and population characteristics every five years (Figure 10.5). The EDHS collects data from a large number of households spread throughout the whole of the country on a wide range of factors, including birth rates, average family size, knowledge of issues such as family planning, mortality (death) rates in different age groups, and the main causes of death and illness.

10.3.2 Cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys

In addition to the size and distribution of the population surveyed (e.g. national or local), surveys can also be either cross-sectional or longitudinal. Cross-sectional surveys are used to gather information on a population at a single point in time, for example, on a certain date, or during a particular month. An example of a cross-sectional survey would be a questionnaire that collects data in a single month on how parents feel about adolescent reproductive health services. Alternatively, a questionnaire might try to determine the relationship between two factors at a particular point in time, such as the religious views of parents and whether they accept or reject family planning services.

Longitudinal surveys gather data over a period of time, which may be several months or even several years. The researcher may then analyse changes in the population’s demographic or epidemiological features as time passes, and attempt to describe and/or explain these changes. For example, a longitudinal survey could discover that the birth rate in a particular region was falling steadily over time, and that this seemed to be related to a rise in the acceptance of family planning methods in the community.

Is a national census a cross-sectional or a longitudinal survey?

It is cross-sectional, because it takes place at one point in time (e.g. every five years).

A community survey may be cross-sectional (e.g. you will conduct a community survey to collect data for your community profile when you are first deployed to a kebele), but if you continue to collect data on the same topics every year for several years, your survey will become longitudinal.

Usually several people are trained to collect the data for a survey, because a large number of individuals have to be asked the same questions and this would take a long time if one person tries to do it alone. The common survey data-collection tools are questionnaires, interviews and focus groups.

10.3.3 Questionnaires, interviews and focus groups

Questionnaires are a list of questions with a space under each one for the researcher to write the answers given by the respondent (the person ‘responding’ to the questionnaire). Alternatively, questionnaires can have several possible answers to each question and the respondent chooses which one best represents their status, knowledge or opinions. Interviews are less formal and the interviewer has a structured conversation with one or more respondents about topics of interest, and writes down the answers based on what the respondent says. Focus groups are guided discussions in a group of people who have agreed to ‘focus’ on a particular subject, sharing their views and experiences in order to shed light on a problem and its possible solutions. The group has a facilitator, who keeps the group focused on the agreed topic and records the points made in the discussion (Figure 10.6). You will learn more about these (and other) data collection methods in Study Session 12.

10.3.4 Basic questions to ask in a community survey

The responses to questionnaires, interviews and focus groups in your community will help you to understand and tackle the priority health problems locally. Questions that relate to these problems might include:

- What are the most important health needs of different groups of people in your community? It is important to establish these health needs from the point of view of people living in your community, as well as the needs expressed by health professionals. Your community survey can be seen as a form of health needs assessment.

- Does the current set of health interventions cover these needs? Are the interventions acceptable to local people in terms of culture and cost, especially to the poorer members of the society? Are the interventions provided as cost-effectively as possible?

- Given the resources available, could your health service cover more needs, or more people, in a more cost-effective way?

- Is it possible to better control the environmental factors that influence health and healthcare? Can other sectors help (education, water, agriculture, public works/roads, etc.)?

Information collected through health research help these questions to be answered better. That is why research is done and why you will be doing a community survey of your own when you have completed your training and are deployed to a kebele. After you have completed your community survey and analysed the results, it will probably raise questions in your mind about the reasons for certain health problems and what you could do about them. One way of finding the answers is to conduct small-scale health research projects, to investigate health-related problems in your community more closely, and to see whether the results help in finding better solutions.

Summary of Study Session 10

In Study Session 10, you have learned that:

- Health research investigates health needs and health-related problems and aims to develop better solutions to resolve them. A community survey is a type of health research aimed at investigating local health needs and suggesting solutions to priority health problems.

- Community surveys and other forms of health research should begin with a clear statement of the problem, have clear objectives and a plan that is directed towards the solution of a particular problem. They should be simple to carry out and the results should be based on observable and accurate evidence.

- Researchers should have appropriate expertise in data collection methods and study design, their findings should be carefully recorded and reported, and the research should be reproducible by different investigators using the same methods.

- Participation of community members, healthworkers, policymakers and other stakeholders in the design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation of health research results is important for maximum acceptability and effectiveness of decisions based on the outcomes. Local stakeholder participation is essential for the success of a community survey.

- Different types of health research can be conducted, including pure or applied research, quantitative or qualitative studies, with cross-sectional or longitudinal designs.

- The results of health research (including community surveys) have most impact if they can influence policy and practice by health professionals and community members at a local level.

- National censuses, large-scale surveys and local community surveys are types of health research that involve the systematic collection of demographic and epidemiological data. The main data collection methods are questionnaires, interviews and focus group discussions.

- The basic questions asked by health researchers focus on the health needs of the respondents, the available interventions and resources, and the possibility that environmental management or collaboration with other sectors could help to resolve identified health problems.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 10

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

First read Case Study 10.1 and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 10.1 A community survey of conditions leading to diarrhoeal diseases

Aster (the Health Extension Practitioner) was concerned that she was referring a large number of cases of severe diarrhoeal diseases to the nearby health centre. Despite the good access of health services in this community, the average number of visits to the health centre for severe diarrhoeal diseases was two to three times for each household every year. Aster noticed that some community members were using the river and unprotected springs as a source of drinking water. She also noticed the practice of open defecation (passing stools in the open fields) by community members. She decided to investigate why these behaviours were happening.

In October 2009, she trained and deployed volunteer data collectors from the community to conduct a household community survey. She gave them all the same questionnaire, which asked simple questions about access to safe drinking water and access to a latrine. The volunteers questioned people in all the households, wrote down the answers given by the respondents and brought Aster the results. She carefully recorded and analysed the data herself, using the same method for all the questionnaires.

The survey showed that 68% of the households did not have access to a safe water supply, and 25% did not have a latrine near their home. Of the 75% of households who had a latrine, many people were not using it due to the following reasons: they preferred open defecation, they disliked being forced to dig the latrine, and they hated squatting over the hole in the latrine (they described it as ‘like calling death to oneself’). Lack of awareness on the mode of transmission of diarrhoeal diseases from drinking water contaminated with faeces was also identified among the community members.

Based on the findings of her survey, Aster made the following recommendations to the community leaders:

- She planned a health education programme at the community level on:

- Awareness creation on the modes of diarrhoeal disease transmission.

- The importance of handwashing with soap and always using latrines in the control and prevention of diarrhoeal diseases.

- The use of household-level water treatment chemicals available in the local market to prevent transmission.

- Community mobilisation for construction of latrines for the 25% of households without a latrine, using locally available resources.

- Promotion of a policy to stop open defecation in the fields.

SAQ 10.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1 and 10.2)

- a.Is the type of research used in Case Study 10.1 applied or basic?

- b.Is it cross-sectional or longitudinal?

In each case, explain your answers by referring to details of the case study.

Answer

- a.Case Study 10.1 is an example of applied research: it focuses on investigating the causes of a prevailing problem (diarrhoeal diseases) and suggested ways of tackling it.

- b.It is a cross-sectional study which was conducted at one point in time: October 2009.

SAQ 10.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1 and 10.2)

- a.Give two examples of quantitative data collected in the community survey in Case Study 10.1.

- b.Give one example of qualitative data collected in the community survey.

Answer

- a.Two examples of quantitative data collected in the community survey are the numbers and percentage of households without latrines, and the number without access to safe water.

- b.An example of qualitative data collected in the community survey is that it sought explanations for the low utilisation of latrines in terms of people’s feelings and attitudes to latrine use, and discovered that there were cultural and practical barriers.

SAQ 10.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1 and 10.3)

If Aster wanted to follow up the results of her community survey by investigating people’s reasons for not using their latrines, what methods could she use to collect more in-depth qualitative data?

Answer

Aster could interview people identified from the survey as having a latrine, but who are unwilling to use it. She may learn more personal in-depth information in a one-to-one interview about why they prefer open defecation. She could also arrange a focus group discussion between people who do use their latrine and people who don’t, so they can share their views and experiences.

SAQ 10.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1, 10.2 and 10.3)

What features of Aster’s conduct of her community survey show that she was being systematic in her approach to data collection and data analysis?

Answer

Aster’s survey was systematic because she gave the same questionnaire to the volunteer data collectors and trained them all to use it in the same way. When they returned the questionnaire, she recorded and analysed all the results herself, using the same method for all the questionnaires.