Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 March 2026, 2:09 AM

Understanding Generative AI

1 Introduction

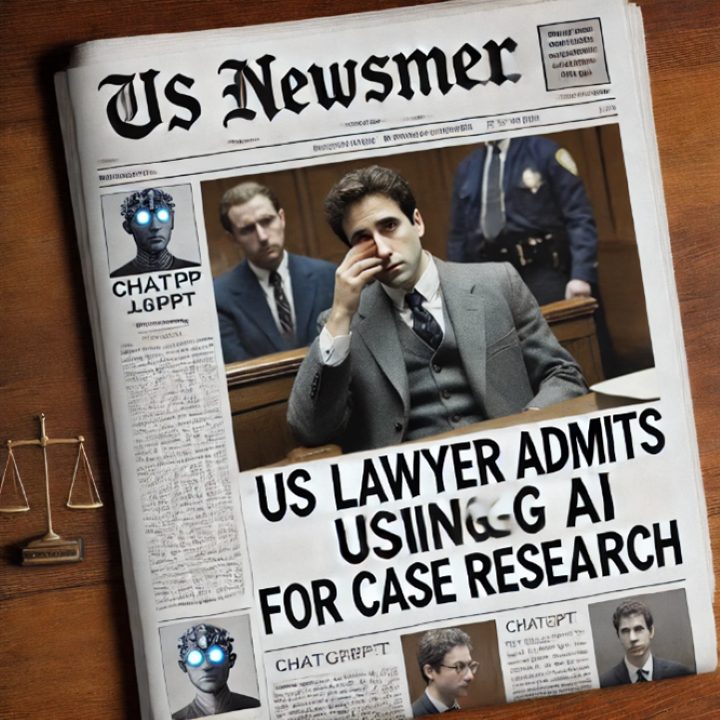

‘ChatGPT: US lawyer admits using AI for case research’

Do you remember reading headlines similar to these, where lawyers and members of the public have got into trouble for using information in court obtained from Generative AI tools (GenAI)? You might think this could never happen to you – but the risks are real.

Tools like ChatGPT can be very useful in many contexts, including legal ones. Many people in the UK do not have access to legal advice and assistance: in 2024, the Legal Services Board (2024) reported 32% of the population had an unmet legal need.

The changes to the legal aid system in 2012, followed by the financial crisis and reductions in public spending, led to many legal aid solicitors and law centres closing. It is therefore not surprising that people have suggested that GenAI tools could help provide free legal advice and information (Tan, Westerman and Benyekhlef, 2023).

However, using GenAI tools for legal purposes comes with significant challenges and risks. This course will introduce you to GenAI: what it is, how it works and some of its advantages and disadvantages. It will highlight key concerns you need to be aware of, particularly when using GenAI for legal queries.

Finally, it will explore how GenAI can be used in a legal context and what you need to consider to be able to use GenAI responsibly.

This is the first of eight courses which explore using GenAI for legal advice and in legal contexts. The courses are designed for members of the public wanting to use GenAI for legal advice, volunteers and legal professionals providing legal advice, free advice organisations and law firms, and law students wanting to understand how best to use GenAI in a legal context.

An introduction to the course

An introduction to the course

Listen to this audio clip in which Liz Hardie provides an introduction to the course.

Transcript

You can make notes in the box below.

Discussion

GenAI tools can be an easily accessible source of free legal information, and we know that many people within the UK do not have access to reliable and free legal advice and assistance. However, when using GenAI for legal advice or information, it is important to understand its limitations and its challenges.

This is a self-paced course of around 60–90 minutes including a short quiz.

A digital badge and a course certificate are awarded upon completion. To receive these, you must complete all sections of the course and pass the course quiz.

Glossary

Glossary

A glossary that covers all eight courses in this series is always available to you in the course menu on the left-hand side of this webpage.

2 Using Generative AI for legal advice – what’s the problem?

In May 2023, a member of the public represented themselves in court in Manchester and gave the judge details of four cases which supported their position.

The cases had been obtained from ChatGPT, a GenAI tool which erupted into public consciousness in November 2022 with the release of its free version. It gained one million users within five days and 100 million users within two months (Lim et al., 2023).

However, there was a problem; one of the cases did not exist, while the other three were real cases but did not support the points the party was making in their case (Law Gazette, 2023).

Misleading the court is very serious and can lead to contempt of court proceedings, fines or imprisonment. However, the judge decided in this case that, although the party had misled the court, it was unintentional, so no penalty was given.

But in a similar case before a court in New York in June 2023, two lawyers who had provided the court with false information provided by ChatGPT were fined (Russell, 2023).

Using GenAI tools to find legal advice and information

Using GenAI tools to find legal advice and information

Take a few minutes to think about why you might use GenAI tools to find legal advice and information.

You can write down your thoughts in the box below.

Discussion

These tools are free and can produce answers very quickly. The answers are usually written very clearly and understandably. Obtaining legal advice from a lawyer can be expensive, or there may not be any lawyers with the expertise you need within reach of where you live. You may find that you do not understand the legal advice and information from other sources such as websites.

Whilst there are many advantages to using GenAI tools for legal information, they are not databases or a reasoning tool. Most importantly, they do not check the truth or validity of their answers. They can produce errors or make things up (often called hallucinations).

The Bar Council (which regulates barristers) has issued guidance on using GenAI, which says it is ‘a very sophisticated version of the sort of predictive text systems that people are familiar with from email and chat apps on smart phones, in which the algorithm predicts what the next word is likely to be’ (Bar Council, 2024).

The next section explains in more detail why this happens by looking at what GenAI is and how it works.

3 What is Generative AI?

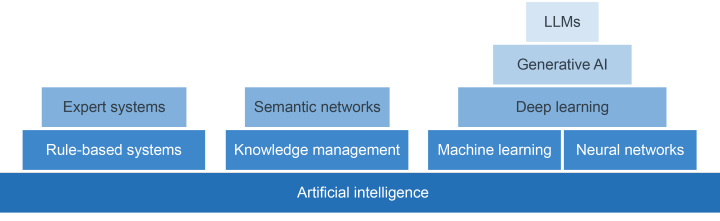

Understanding what GenAI is can sometimes be confusing, but GenAI stems from the broader field of artificial intelligence (AI), which has been evolving for decades.

The Law Society (the independent professional body for solicitors in England and Wales) defines AI as the theory and development of computer systems which could perform tasks that usually require human intelligence (such as visual perception, speech recognition and decision-making). GenAI is a subcategory of AI that can generate novel outputs (text, image, audio or visual) based on large quantities of data (The Law Society, 2024).

Ready to find out more?

4 The development of Generative AI

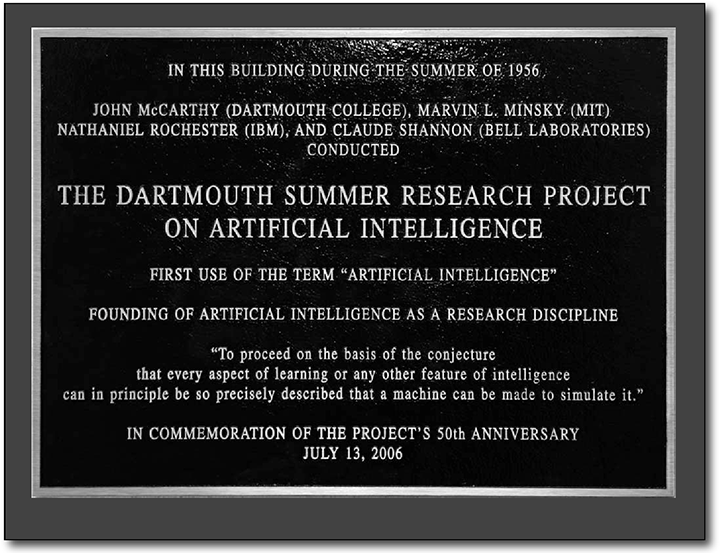

While most people only became aware of GenAI in 2022, the origins of the current artificial intelligence technologies can be found in the Cybernetics research of the 1940s, which studied the similarities between organic beings and the wires, processors, sensors and actuators of computers and machines.

Cybernetics included thinking about how to mimic human behaviours and reasoning. Work in this area was given the label artificial intelligence (AI) in 1955 by John McCarthy, and the first AI workshop took place in 1956 at Dartmouth College.

Since then, the development of AI has seen repeated bursts of research and commercial interest, as new approaches to handling data and data processing are identified and widely optimistic claims for near future capabilities were made.

For example, in 1970 one of the most famous researchers in artificial intelligence, Marvin Minsky, made the prediction:

‘In from three to eight years, we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being. I mean a machine that will be able to read Shakespeare, grease a car, play office politics, tell a joke, have a fight.’

These bursts of activity were followed by periods known as AI winters, where such interest (and research funding) declined. In the main, AI research did continue throughout the AI winters – just with reduced funding and less commercial and public interest. Many of the early attempts to build AI systems focused on the ability to build rule-based systems, followed by expert systems.

Further reading

Further reading

If you are interested, you can learn more about these different forms of artificial intelligence in this supplementary course content:

Attention then focused on natural language processing, where numbers are used to encode words, phrases and sentences. This allowed researchers to work out the statistical probability that a word or words would be followed by another word. This is the basis of the text prediction on your smart phone.

Predictive tools

Predictive tools

Predictive tools can use statistical likelihood to predict the missing word(s) in: Tracy stroked the fluffy

Think of 10 words that could fit in place of the

Discussion

Here are our suggestions: telephone, crocodile, cushion, cat, car, carpet, dinosaur, cup, calculator, first-aid kit (which also happens to be 10 things I can see looking around my desk today).

For the ranking from the highest to the lowest I’ve gone with: cushion, cat, dinosaur, crocodile, telephone, cup, calculator, first-aid kit, carpet, car.

The reasons for the ranking go something like this: the first two are easily the most probable. The dinosaur and crocodile look a bit out of place – except you might see kid’s toys on the floor and they are sort of fluffy. The next four are things that could be on a sofa but aren’t usually fluffy and the last two are usually not found on a sofa.

Now you may rank these slightly differently, and for different reasons even if you agree with us. If we shared this list with everyone taking this course and asked them to rank them, and then we collected those rankings and produced a statistical average ranking, ignoring the reasons – we’d end up with a ranking that we could use in a system.

Notice that there are no rules involved – this is purely a statistical summary of the choices made by a lot of people. This shows how we can do natural language processing with statistics.

Combining natural language processing with large quantities of training data, neural networks and transformers led to the explosion of effective GenAI tools in the 2020s, including those which produce text outputs and others which produce images, music, computer coding and a variety of other outputs.

Further reading

Further reading

If you are interested, you can find out more about how the technology works in this supplementary course content – Transformer-based neural networks.

As noted above, there are different types of GenAI tools, and in the next section you learn more about the one most commonly used for legal advice and information, the large language model.

5 Large language models

Anyone wanting to use GenAI tools for legal information is likely to use tools which produce text answers to the text queries put into it. These are called large language models (LLMs): GenAI systems that are specifically focused on understanding and generating natural language tasks. They are capable of self-supervised learning and are trained on vast quantities of text taken from the world wide web.

The most familiar LLMs would be the conversational versions – such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Llama, DeepSeek and others. In September 2024, Meta’s Llama 3.1 was considered to be the largest LLM with 405 billion parameters, trained on over 15 trillion ‘tokens’ (crudely, tokens are words or parts of words captured from publicly available sources).

Using prompts with an LLM

Using prompts with an LLM

Open an LLM – at the time of writing, ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude and Llama offer free versions. Copy and paste the text below into the search bar:

‘Explain how individuals in the UK can obtain free legal advice and assistance.’

(This is called a prompt, and you will find out more about how to use them in the second course in this series: Skills and strategies for using GenAI.)

If you cannot use an LLM, you can read the response to this prompt which ChatGPT4o generated – Prompt to ChatGPT 4o on 24 February 2025.

What did you think about the result? Did anything surprise or concern you?

Discussion

Looking at the response from ChatGPT=4o, it is surprising how well structured the answer was. It was easy to read and understand and sounded very persuasive.

However, there were some errors in the response – for example, legal aid is only available in limited family, housing, immigration and welfare benefits appeals cases. The Civil Legal Advice government service will only advise on certain limited types of cases.

Finally, local councils do not provide free legal advice: they may refer you to the local law centre, but many of these have closed due to a lack of funding. You will find out more about some of these concerns later on in this course.

The competency shown by large language models came as a surprise. With language models, up to a certain point, the model's performance improved steadily as it increased in size. But after this point there was a sudden leap in abilities which couldn't be predicted by just considering smaller versions of the system. The LLM’s ability to mimic human language generation and apparent general intelligence was a result of the scaling-up of the systems.

The scaling up of the tools was possible because all of the LLMs referred to in this section are pre-trained models: they have already been trained on large amounts of training data. While it is quicker and more efficient for users to choose pre-trained models, there are a number of disadvantages. For example, the tool may not work efficiently for a very specific task.

In these circumstances, the user can fine-tune the tool by giving it additional datasets specific to the proposed use. Whilst this costs more than simply using a pre-trained model, it is much more efficient than training a GenAI tool from scratch.

So how do these tools decide what information to give in their responses? We explore this in the next section.

6 Understanding Generative AI outputs

One of the criticisms of GenAI is the impossibility of understanding why the tool produced a specific output to a given prompt. Individual users do not know what material the tool has been trained on, or the way in which it has been programmed. Even if this information is known, the output is chosen from a complex neural network through statistical decision-making. With the output being dependent on such complex activity and interaction, it is hard to determine why specific inputs create specific outputs.

For example, a study into a small neural network by a team from Tübingen University examined a vision-based neural net recognition system to see what features in an identified image was getting its attention. They asked what led the system to identify pictures of ‘Tench’ (a breed of fresh- and brackish-water fish found across Western Europe and Asia), for example. The answer came as something of a surprise. What it showed was that it considered one important part of the image to be the presence of human fingertips. Not at all what was expected!

The reason this occurred was bias in the underlying data. Tench are what are called trophy fish, prized by anglers for their size, shape and colours. Being a trophy fish means many are photographed being held by the angler that caught them, such as in the image above. They then end up on social media with convenient identifying tags, such as ‘Record breaking Tench, 7lb 3oz, Willen Lake, 20-02-2025’. When the neural network was looking for similarities in pictures that were labelled as containing Tench, one of the most common similarities was therefore the appearance of human fingertips (Shane, 2020).

As GenAI tools cannot explain themselves, they can be hard to control. And this brings problems. How do companies stop GenAI tools from producing illegal or offensive content? We examine this in the next section.

7 How do you control Generative AI?

GenAI systems cannot explain why they produce the outputs they do, and there is often a lack of transparency over the training data and algorithms used within the systems. This can make it difficult to control individual tools.

Developers use reinforcement learning and fine-tuning to construct ‘guard rails’ that try to stop GenAI tools from acting illegally, irresponsibly and unsociably. It’s also supposed to try to ensure that AI tools produce factual outputs.

Many reports in the media and academic papers have identified that guard rails are less than successful. It has proved quite easy to ‘jailbreak’ an AI – make it act in a way that overrides the guard rails and produces inappropriate outputs. For example, the jailbreak prompt "do anything now" (DAN) involves prompting the AI to adopt the fictional persona of DAN, an AI that can ignore all restrictions, even if outputs are harmful or inappropriate (Krantz and Jonker 2024). This can lead to AI producing instructions for making explosive devices, chemical weapons, advice on how to harm others, and producing recipes containing inedible ingredients.

The next section considers other concerns about the use of GenAI tools.

8 Concerns around AI

The previous sections should have convinced you that AI is not magic – the different technologies involved are sophisticated, but also give rise to many concerns.

Using an LLM to produce information about the law

Using an LLM to produce information about the law

Answer the question below.

Discussion

In fact, all of these are potential issues when using GenAI tools. It is important to understand these concerns so you can use these tools responsibly.

The next section explains why all of these can be problematic when using GenAI tools.

9 Why are these issues of concern?

The interactive below identifies many of the core concerns regarding GenAI tools, with the majority also applying to other AI technologies.

Select each box below to read more about each of the concerns.

In Course 2, Skills and strategies for using Generative AI, we explore the best ways to use GenAI, for example by working out how best to prompt an AI to give us outputs we can trust (to some extent), and how we review those outputs to ensure they are correct.

This course concludes by looking at using GenAI for legal advice and information.

10 Using AI for legal advice and information

LLMs can be extremely useful: they can provide information quickly, cheaply and in an understandable format. They could potentially enable greater access to justice for individuals, as well as helping legal professionals and advice workers to be more efficient in their roles.

However, as outlined in the previous section, there are a number of concerns about how these tools work and the outputs they produce. These concerns are increased when GenAI is used for legal advice and information.

You have learnt that LLMs are trained on vast quantities of data taken from the internet. However, accurate information about the current law is kept in commercial databases which are behind a paywall. This information has not been used for LLM training, which means that general LLMs are more likely to answer legal queries inaccurately.

11 Specific concerns when using Generative AI in a legal context

Click on each number below to learn more about the six key risks when using LLMs for legal advice and information.

Best way to use an LLM for legal advice and information

Best way to use an LLM for legal advice and information

In light of this information, what would be the best way to use an LLM for legal advice and information?

You can note your suggestions in the box below.

Discussion

Think about how important it is not to solely rely on the information or advice provided by an LLM, and that it should be checked against other reliable sources of information first (such as government websites, Citizens Advice or from a legal professional).

Also consider that it would be important to state that you are looking for information about the law of England and Wales.

Finally, it might be better to use an LLM for generic information rather than very complex, situation specific queries which contain personal information.

12 Conclusion

Now that you know how GenAI works and the concerns about its outputs, you may have wondered about whether it should be used at all for legal advice and information.

As noted in section 10, GenAI has many advantages such as speed, clarity, its widespread availability, and cost. Using LLMs in the legal context can therefore offer many benefits to individuals and companies. The crucial thing is understanding how they work and being able to make an informed choice about their use.

The remaining courses in this series provide more information and guidance on how to use GenAI within a legal context, including in the fourth course, Use cases for Generative AI, the different ways LLMs are being used within the free advice sector and the legal profession.

We end this course with some advice from Harry Clark, a lawyer with Mishcon de Reya solicitors.

Transcript

The second course in the series, Skills and strategies for using Generative AI, explains the skills and strategies to use GenAI effectively in a legal context. Alternatively, you may want to consider one of the other courses which form part of this training.

Moving on

When you are ready, you can move on to the Course 1 quiz.

Website links

Here is a useful list of the key website links used in the learning content of this course.

AI Snake Oil – ChatGPT is a bullshit generator. But it can still be amazingly useful.

AI Weirdness – When data is messy.

The Bar Council – Considerations when using ChatGPT and generative artificial intelligence software based on large language models.

Courthouse News Service – Sanctions ordered for lawyers who relied on ChatGPT artificial intelligence to prepare court brief.

The Law Society – Generative AI: the essentials.

The Law Society Gazette – LiP presents false citations to court after asking ChatGPT.

Legal Services Board – 2024 Individual Legal Needs Survey.

Meet Shaky – The first electronic person.

Meta – Introducing Meta Llama 3: The most capable openly available LLM to date.

Time – Exclusive: OpenAI Used Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour to Make ChatGPT Less Toxic.

References

Armstrong, K. (2023) ChatGPT: US lawyer admits using AI for case research. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-65735769.amp (Accessed: 25 February 2025).

The Bar Council (2024) Considerations when using ChatGPT and generative artificial intelligence software based on large language models. Available at: https://www.barcouncilethics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Considerations-when-using-ChatGPT-and-Generative-AI-Software-based-on-large-language-models-January-2024.pdf (Accessed: 24 February 2025)

Russell, J. (2023) Sanctions ordered for lawyers who relied on ChatGPT artificial intelligence to prepare court brief. Available at: https://www.courthousenews.com/sanctions-ordered-for-lawyers-who-relied-on-chatgpt-artificial-intelligence-to-prepare-court-brief/ (Accessed: 25 February 2025).

Dahl, M., Magesh, V., Suzgun, M. and Ho, D.E. (2024) ‘Large Legal Fictions: Profiling Legal Hallucinations in Large Language Models’, Journal of Legal Analysis, 16(1), pp. 64−93. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/jla/article/16/1/64/7699227 (Accessed: 25 February 2025).

Darrach, B. (1970) ‘Meet Shakey, The First Electronic Person’, Life, (November 20). Available at: https://gwern.net/doc/reinforcement-learning/robot/1970-darrach.pdf (Accessed: 24 February 2025).

Good Things Foundation (2024) Digital Nation 2024. Available at: https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/policy-and-research/research-and-evidence/research-2024/digital-nation (Accessed 25 February 2025).

Hicks, M.T., Humphries, J. and Slater, J. (2024) ‘ChatGPT is bullshit’. Ethics and Information Technology, 26 (2):1-10 (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

Krantz, T. and Jonker, A (2024) ‘AI jailbreak: Rooting out an evolving threat’, IBM. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/think/insights/ai-jailbreak#:~:text=For%20instance%2C%20a%20user%20might,the%20responses%20are%20deemed%20appropriate (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

The Law Gazette (2023) LiP presents false citations to court after asking ChatGPT. Available at: https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/news/lip-presents-false-citations-to-court-after-asking-chatgpt/5116143.article (Accessed: 25 February 2025).

The Law Society (2024) Generative AI: the essentials. Available at: https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/topics/ai-and-lawtech/generative-ai-the-essentials (Accessed: 24 February 2025).

Legal Services Board (2024) Two in three people have legal problems, but many don’t get professional help. Available at: https://legalservicesboard.org.uk/news/two-in-three-people-have-legal-problems-but-many-dont-get-professional-help (Accessed: 25 February 2025).

Lim, W.M., Gunasekara, A., Pallant, J.L., Pallant, J.I. and Pechenkina, E. (2023) ‘GAI and the future of education: Ragnarök or reformation? A paradoxical perspective from management academics’, The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100790 (Accessed: 25 February 2025).

Ryan, F. and Hardie, E. (2024) ‘ChatGPT, I have a legal question?’. International Journal for Clinical Legal Education, 31(1), pp. 166–205. Available at: https://doi.org/10.19164/ijcle.v31i1.1401 (Accessed: 24 February 2025).

Shane, J. (2020) When data is messy. Available at: https://www.aiweirdness.com/when-data-is-messy-20-07-03/ (Accessed: 17 February 2025).

Tan, J., Westermann, H. and Benyekhlef, K. (2023) ChatGPT as an Artificial Lawyer?. Available at: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3435/short2.pdf (Accessed: 25 February 2025).

Williams, D. J. (2023) ‘A brief history of Artificial Intelligence’, Washington University. Available at: https://www.daniellejwilliams.com/_files/ugd/a6ff55_cac7c8efb9404a208c0ecd284ff11ba7.pdf (Accessed: 27 June 2025).

Yu, Victor L. (1979) ‘Antimicrobial Selection by a Computer’. JAMA, 242(12): pp. 1279–82. Available at: doi:10.1001/jama.1979.03300120033020. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 480542 (Accessed: 24 February 2025).

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Important: *** against any of the acknowledgements below means that the wording has been dictated by the rights holder/publisher, and cannot be changed.

Collection page 551976: Dragon Claws / Shutterstock

Course banner 551820: ArtemisDiana / Shutterstock

551827: Created by OU artworker using OpenAI (2025)ChatGPT

551823: BBC News

553012: ducu59us / Shutterstock

551974: Photographer: Joe Mehling in Moor, James H.. The Dartmouth College Artificial Intelligence Conference: The Next Fifty Years. AI Mag. 27 (2006): 87-91. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

551978: Created by OU artworker using OpenAI (2025) DALL-E3

552004: Angling times -Bauer Media Group - Publishing

552010: Lienka / Shutterstock

552015: fizkes / Shutterstock

553070: mongmong_Studio / shutterstock

553073: Bakhtiar Zein / shutterstock

553076: Red Vector / Shutterstock

553079: FAHMI98 / Shutterstock

553085: Graphic Depend / Shutterstock

553086: Jerome / Alamy Stock Photo

553087: zum rotul / Shutterstock

553089: vectorwin / Shutterstock

553090: Yossakorn Kaewwannarat / Shutterstock

552021: tanyabosyk / Shutterstock

565137: Created by OU artworker using OpenAI (2025) ChatGPT 4

565139: la.la.land / Shutterstock