Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 20 November 2025, 12:50 AM

Health Management, Ethics and Research: 14. Research Strategies and Study Designs for Small-Scale Research

Study Session 14 Research Strategies and Study Designs for Small-Scale Research

Introduction

In the previous study sessions you became familiar with conducting a community survey and using the data to create a community profile for the kebele in which you will be working. You were also introduced to the general principles of health research and how they apply to any small-scale research projects that you may be able to conduct as a Health Extension Practitioner in a rural area at some time in the future. Although you may not be involved directly in research at an early stage in your career, it is important that you know about some simple research methods and how you could use them to inform your understanding of health problems in your area.

Selection of a research strategy and study design is the most important decision a researcher has to make before beginning any research activity. The main focus of this study session is to outline the essential components of research strategies and study designs, which include defining the population of interest and the study variables. These terms will be fully explained in this study session. You will also learn about the selection of an appropriate study design for your particular study population and variables, and how to collect useful data that has the potential to improve the health services you provide in your community.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 14

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

14.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 14.1, 14.3 and 14.4)

14.2 Identify and define appropriate study populations for a specific type of research study. (SAQ 14.1)

14.3 Identify the study variables in descriptions of small-scale research projects presented to you. (SAQs 14.1, 14.2 and 14.3)

14.4 Describe the three survey designs most commonly used in small-scale health research and comment on their relative advantages and disadvantages. (SAQ 14.4)

14.1 What is the study population?

In your work you may have identified something interesting that you would like to investigate further and which could form the basis of a possible research problem. It will probably involve particular groups, for example young people, or people with a specific health problem such as malaria. So, investigating the problem will almost certainly require a research project. These particular groups of interest are referred to as the study population. This study population is the total members of a defined class of people, objects, places or events selected because they are relevant to your research question. For example, if you want to study maternal healthcare, the study population would be all the pregnant women who are under your care. However, a study population may consist of villages, institutions, records, or events such as death due to accidents, etc.

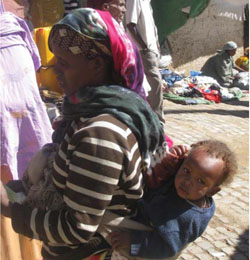

In any research study, the study population has to be clearly defined according to particular characteristics such as age, sex, residence or geographical accessibility to health services (Figure 14.1). The way you define your study population depends on the problem you want to investigate and on the objectives of the study. For example to investigate health problems of orphans whose parents have died of HIV/AIDS, then your study population could be all children below twelve years of age whose parents have died as a result of HIV/AIDS. On the other hand, to investigate the problem of worm infestation in primary school children your study population could be all primary schools in your kebele.

If you want to make a study of malaria in your kebele, what would be your study population?

Your study population would be all the people in your kebele. Some of these people will have malaria, but you will probably want to consider the situation of everyone in your community.

When considering what your study population might be, there may also be practical questions to consider such as how easy is to get access to the study population you are hoping to study (Figure 14.2).

14.2 Variables in health research

If you do have a chance to do some research in your village, then you will need to know about what sorts of variables might be suitable for study. A variable is something that can take on different values. A variable may be in the form of numbers (such as weight or age), or non-numerical characteristics (such as occupation, ethnicity, education level or gender). It can be a characteristic of a person, object, place, event or phenomenon. For instance, a water filter is an object that exists in several different types (or variables), so you could study the effectiveness of different water filters as the variable in a research study on prevention of diarrhoeal diseases. The type of house that people live in is a variable ‘place’ that affects health, and an accidental injury is an example of a variable ‘event or phenomenon’ that you could study.

Variables may take numerical (quantitative) or non-numerical (qualitative) values. Measurements such as weight expressed in kilograms or pounds, height expressed in metres or centimetres, income expressed in dollars or birr, and number of children per family are examples of numerical or quantitative variables.

Which of these is a quantitative variable? Explain why.

- a.Marital status.

- b.Temperature of person suffering from fever.

- c.Travel time to the nearest health centre.

- d.Number of visits to a Health Post in one year.

- e.Family support from grandparents and other elders.

b., c., d. are quantitative variables, because we can use numbers to express, count or measure them.

Qualitative variables are attributes described in terms of the presence or absence of certain characteristics, such as diseased or non-diseased, smoker or non-smoker, married or unmarried. Qualitative variables may also be descriptive, such as occupation or political views. In the question above, items A (marital status) and E (family support) are qualitative variables.

Knowing about variables is very important, because you will not be able to undertake useful research or discuss your research findings unless you understand which variables you are dealing with. The identification of variables as non-numerical or numerical determines whether the data is qualitative or quantitative, and this in turn determines the method of analysing the data. Remember that you have already learned about qualitative and quantitative data in Study Session 12.

Why do you think it is important to know what your variables are before starting any research?

Knowing your study variables will help you to identify clearly what measurements to make or what data to collect from the study population.

14.3 Types of study design

If you are interested in doing some small-scale research in your kebele, then you will certainly need to think carefully about the design of your study. Study designs can be observational (in which the researcher simply observes what is going on), or experimental (in which the researcher intervenes in some way and then observes what happens as a result).

14.3.1 Observational and experimental studies

In an observational study you just observe and analyse your study subjects or situations in their natural condition, but the researcher does not intervene in any way. However, the observations should not just be a haphazard collection of facts; observational studies should apply the same rigour as experimental studies by recording the observations in a systematic way that can lead to meaningful interpretations. You are more likely to be involved in observational studies than in experimental studies.

An experimental study is a type of research design in which some of the conditions are under the direct control of the researcher. He or she intentionally alters one or more factors (e.g. the behaviour of participants, or their circumstances and situations), and then measures the outcomes to analyse the effects of the alteration. For example, you could implement a health education campaign on the benefits of immunization (this is the intervention), and then measure any improvement in immunization coverage rates (by analysing the outcomes of your intervention).

A study in your village is set up to see whether people are using their insecticide treated bed nets (ITNs) correctly (Figure 14.3). You also want to know whether the number of malaria cases is influenced by incorrect use of ITNs. Is this an experimental study or an observational study?

This is an observational study, because you are observing how people use ITNs without any intervention from you, and you are counting the number of malaria cases associated with incorrect use of ITNs.

Next, you teach people how to use ITNs correctly and you distribute new nets to households where the ITNs were damaged. Then you measure the outcomes in terms of any reduction in malaria cases. Is this an experimental study or an observational study?

It is an experimental study. You intervened in the situation by giving education about ITNs and distributing new nets; then you measured the outcome in terms of any reduction in malaria cases.

One thing we have to remind you here is that it would not be ethical to introduce ITNs to some households in your community and intentionally leave other households without nets, in order to conduct an experimental study on the effect of ITNs on preventing malaria. The knowledge that ITNs protect people from the mosquitoes that transmit malaria is already well established by research. Therefore, there is no need for you to duplicate this research and deny protection to some families by leaving them out of the ITN distribution programme. This example reminds you that your actions in designing a research study must observe strict ethical guidelines (refer back to Study Sessions 7 and 8).

Another study in your village is set up to measure how much malnutrition or stunting there is in the children aged six months to three years (Figure 14.4). Is this an observational study or an experimental study?

This is an observational study, because you are describing malnutrition or stunting without any intervention, such as introducing nutritional supplements.

14.3.2 Types of observational studies

As a Health Extension Practitioner you will probably only be directly concerned with observational studies. These generally take the form of sample surveys (of selected individuals) or population surveys (covering everyone in the population), where the sample or the population is observed for various characteristics. This may be done by interviewing study subjects, using questionnaires or focus groups, by obtaining measurements of physical characteristics (e.g. height or age), or by simply extracting information from existing sources, such as disease registries or hospital records. The most common type of study design you will be involved in is the observational survey, in which information is systematically collected from your study population on a specific topic.

There are three types of observational survey which are most likely to use if you conduct a small-scale research project, and each has a different study design. They are:

- cross-sectional study

- case-control study

- cohort study.

These are just three of many types of research study. These three will be covered in more detail in the sections that follow.

14.3.3 Cross-sectional studies

You may remember from Study Session 10 that cross-sectional studies look at something that is going on at a particular moment in time. If you do a cross-sectional study, you would collect information about the current situation, for example the current state of a particular disease in a particular section of your community, or the current exposure of a certain group of individuals in your community to an infection. Therefore, in cross-sectional studies the information on the possible cause and the possible effect is collected at the same time. However, the problem with cross-sectional studies is that there is no way of knowing whether the possible cause is really responsible for the effect you measured – or could it be the other way around? The following example illustrates what we mean by this problem.

A cross-sectional study has been set up in your village to see if children who are underweight are more likely to get measles than other children of normal weight. The study finds that more children who are underweight have measles than those who are of normal weight. Does this mean that underweight children are more likely to get measles, or that children become underweight because they have been ill with measles?

You would not know whether they had become infected with measles because they were underweight, or whether they were underweight because they had been ill with measles. A cross-sectional study cannot resolve this uncertainty because the information was collected at just at one point in time.

Cross-sectional studies aim at describing the distribution of certain variables in a study population at a certain time, for example in the last month. Examples might include studies of:

- Physical characteristics of people: e.g. surveys of the occurrence of tuberculosis, HIV, malnutrition, high blood pressure, diabetes, anaemia, etc.

- Physical characteristics of the environment: e.g. evaluation of latrine usage, access to safe water supply, distance from the nearest health centre, etc.

- Demographic or socio-economic characteristics of people: e.g. their age, education, marital status, number of children and income.

- The behaviour or practices of people and their knowledge, attitudes, beliefs or opinions, which may help to explain that behaviour: e.g. attitudes to contraception, or harmful traditional practices, healthcare-seeking behaviour if a child has measles or diarrhoea, etc.

- Adverse events that occurred in the population, e.g. the occurrence of road traffic accidents or burns, and natural disasters like flooding or drought.

Cross-sectional studies usually cover a selected sample of the population. For example, it would be impossible to study all children with measles in a country, so a sample of children with measles is chosen randomly without any bias in the selection. Data are collected at the same time from the sample of children on the risk factor or characteristic (in the example above, it is being underweight) and the disease condition (having measles). If a cross-sectional survey covers the total population of a country it is called a census (as you already learned in Study Session 10). A cross-sectional survey of a sample of the population is cheaper than doing a census because it consumes fewer resources. A cross-sectional survey may be repeated at a later date in order to measure changes over time in the characteristics that were studied. Case Study 14.1 gives a simple example of a cross-sectional study.

Case Study 14.1 A cross-sectional study on household characteristics

A questionnaire was sent to 250 individuals who had visited a Health Post. They were asked information about the layout of their home, such as type of floor covering and number of windows. The investigators wished to determine the number of people affected with fever and cough in the previous month and whether there was any relationship between household characteristics and the risk of having these symptoms, which may possibly indicate tuberculosis.

What feature of Case Study 14.1 indicates that the study design is cross-sectional?

A population sample was surveyed and asked questions about diseases suffered during a short period of time (the last month). So this is a cross-sectional study design.

14.3.4 Case-control studies

If you want to find out more about health conditions in your village it would be necessary to use a slightly more complicated research design than a cross-sectional study. Usually, this will involve a case-control study. You begin by selecting two groups for comparison: one group of the population (the cases) who have a characteristic that you wish to investigate (such as mothers whose child died within one month of birth, or children with malnutrition), and another group (the controls) where that problem is absent. The aim of a case-control study is to find out what factors have contributed to the problem under investigation. Case Study 14.2 gives an example to illustrate this type of study.

Case Study 14.2 A case-control study of the causes of newborn deaths

If you want to study the causes of neonatal (newborn) deaths in your area, you would first select the cases (babies who died within the first month of life) and the controls (babies who survived their first month of life). Then you would interview their mothers to compare the history of these two groups of babies, to determine whether certain factors are more common among the babies who died than among those who survived.

What feature of Case Study 14.2 indicates that this is a case-control study?

Two groups were compared to see if there were any differences in their situation that could explain why the cases died within the first month of life and the controls survived the first month. So this is a case-control study.

It is important to ensure that cases and controls in your study come from the same study population. For example, in a case-control study of vaccination of pregnant women against tetanus, where cases of unvaccinated women are being selected from a particular health centre, controls should be selected from mothers who have attended vaccination at the same health centre. If controls are selected from another centre, they would not be from the same study population and therefore they would not be directly comparable to the cases.

14.3.5 Cohort studies

In order to study a health issue in more detail, it may be necessary to follow a group of people over a long period of time to see which members of the group (or cohort) develop the condition. As you can imagine this type of study is complicated and may be very expensive because it covers a long time. Usually this type of study is done by external agencies such as university researchers or NGOs.

The term cohort describes a specific group of people who are all in a particular situation during a certain period of time, for example, everyone who was born in a particular year, or everyone who shares a particular characteristic (e.g. all farmers, or all women of childbearing age). If these people are studied over a long period of time to see what diseases they develop, this is called a cohort study. The most common type of cohort study begins with a population who share the same general characteristics (e.g. all men aged between 40 and 50 years), but then compares those individuals in the cohort who are exposed to a disease risk factor (e.g. the tobacco smokers) with those individuals in the cohort who are not exposed to the risk factor (in this example, the non-smokers). Then you follow everyone in the cohort over a period of months or years, and compare the occurrence of the problem that you expect to be related to the risk factor (for example, lung cancer or pneumonia) in the two groups. This allows you to determine whether a greater proportion of those with the risk factor (in this example, smoking) are indeed affected by the disease.

What is the main difference between the health of ‘smokers’ in a cohort study and that of the ‘cases’ in a case-control study?

Everyone in a cohort study is well at the outset – including the smokers in our example – whereas the cases in a case-control study all have the disease ‘problem’ at the outset of the study.

Cohort studies may take a long time to yield meaningful results, so they are generally expensive to conduct. However, they have the great advantage of resolving the ‘cause or effect’ problem we mentioned earlier in relation to cross-sectional studies. Because everyone in the cohort is well at the beginning of the research period, it is possible to say that (for example) being a smoker is a contributory cause of lung cancer, if the smokers develop more lung cancers than the non-smokers over time.

14.4 Selecting the appropriate study type to investigate a particular problem

The choice of your study design may depend on the following factors:

- type of problem

- knowledge already available about the problem

- resources available for the study.

For example, as we said earlier, cohort studies are very expensive because they have to follow-up a large number of individuals over a long period of time until the results become clear. Some possible investigations, and the type of study design which would be most suitable in each case, are shown in Table 14.1.

| Investigation | Appropriate study type |

|---|---|

| Investigation of current practice, e.g. treatment of fever at a household level | Cross-sectional study |

| Investigation of a disease which is rare in the community, e.g. breast cancer | Case-control study |

| Investigation of multiple exposures to a single disease agent, e.g. HIV/AIDS | Case-control study |

| Investigation of outcomes of an intervention, e.g. protecting a water source (Figure 14.5) and observing the number of diarrhoea cases in a community over time | Cohort study |

Summary of Study Session 14

In Study Session 14, you have learned that:

- Defining the study population and study variables, and choosing the study type, are an essential starting point for every research project.

- The way you define your study population depends on the problem you want to investigate and on the objectives of your study.

- Variables may be numerical or non-numerical, so the data collected may be quantitative or qualitative, and this determines the appropriate method of analysing the data.

- Study designs may be observational or experimental. Observational studies involve making observations. Experimental studies involve modifying or changing something about the study participants and looking at the effect of this intervention.

- The three common observational study designs are cross-sectional, case-control and cohort studies, all of which involve a survey of some kind.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 14

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

First read Case Study 14.3 and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 14.3 Nutritional problems of women and children

You suspect that a large proportion of women in your kebele are malnourished, in particular women of childbearing age. You would like to determine the nutritional status of the women, assessing this in terms of their weight relative to their height.

SAQ 14.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 14.1, 14.2 and 14.3)

- a.In Case Study 14.3, who will be your study population?

- b.What study variable would you investigate? Is this a numerical or a non-numerical variable?

- c.What type of study design will you choose and why?

Answer

- a.The study population is the total members of a defined class of people, objects or events. Therefore, women in the childbearing age group will be your study population for this research project.

- b.The variable you will consider is their nutritional status, which is assessed in terms of their weight relative to their height. This is a numerical variable.

- c.A cross-sectional study design will be appropriate, because it is possible to assess the current nutritional status of the study population and it will be cheaper than the other two study types.

SAQ 14.2 (tests Learning Outcome 14.3)

You also want to know whether the women perceive their nutritional status as a problem. Furthermore you would like to know whether and how the women could contribute to improving their nutritional status.

- a.What questions could you ask mothers in order to shed light on the causes of malnutrition?

- b.What research tool would you use to ask these questions to ensure that the same data are collected from every respondent? (Think back to Study Session 10.)

Answer

- a.You may ask the mothers about their perceptions, symptoms and causes of malnutrition, and their current diets. Also whether they think it would be possible to improve their nutrition, and if not, what are the barriers preventing this.

- b.A structured questionnaire would be a systematic way to ask each woman about the same issues in the same way.

SAQ 14.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 14.1 and 14.3)

What other possible study variables will you investigate in Case Study 14.3?

Answer

We don’t know exactly what you suggested, but we expect you will have thought of at least some of the possible list of variables below:

woman’s age

number of children

education

ethnicity

types of food in the diet.

Now read Case Study 14.4 and then answer the question that follows it.

Case Study 14.4 Reducing the number of cases of malaria

In your area an indoor spraying programme was completed recently to try to reduce the mosquito population. Nevertheless, the number of malaria cases shows peaks in certain households in the kebele, which you cannot explain. You suspect that there may have been opposition to the spraying in some households, and want to find out if there is a relationship between the houses that were sprayed and the occupants who have suffered from malaria since the spraying was done.

SAQ 14.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 14.1 and 14.4)

Describe the study design that you would use in Case Study 14.4 and explain why you chose it.

Answer

In the example in Case Study 14.4, a cross-sectional study design will be most appropriate. You would ask every household at the same point in time whether they had accepted or refused to have their houses sprayed during the recent programme, and whether any members of the household have suffered from malaria since the spraying was done. This would be a suitable study design because it will give you a quick answer about whether those households where spraying was not done have the most cases of malaria. In addition, it would be cheap to conduct.

You may instead have suggested a case-control study. You would investigate whether malaria cases were more likely to come from unsprayed households, whereas people who did not develop malaria (the controls) came mainly from sprayed households. This would also be a suitable study design for investigating this problem, so would be a correct answer. However, it would be more complex and expensive to undertake than a cross-sectional study, so the cross-sectional design is preferable.