Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 23 November 2025, 10:00 AM

Ethical and responsible use of Generative AI

Introduction

Did Taylor Swift endorse Donald Trump in the 2024 presidential election in the USA?

Trump appeared to think so, sharing on social media some artificial intelligence (AI) generated imagery that appeared to suggest this.

However, a month later, Swift made public her support for Kamala Harris, the other candidate, doing so because of her concerns about the misinformation spread by the false AI-generated images, saying:

“It really conjured up my fears around AI, and the dangers of spreading misinformation. It brought me to the conclusion that I need to be very transparent about my actual plans for this election as a voter. The simplest way to combat misinformation is with the truth.”

This example may make you smile or roll your eyes at the hype surrounding elections.

However, it is an example of how the unethical and irresponsible use of Generative AI (GenAI) can lead to real-world problems. The endorsement of politicians by celebrities has always been important (for example, Frank Sinatra’s endorsement of John F Kennedy), and with 53% of USA adults saying they were a fan of Taylor Swift in March 2023, her fans were a voting bloc which couldn’t be ignored.

This course will explore the importance of using GenAI ethically and responsibly in the context of the legal profession. It will consider some of the ethical concerns around GenAI and how to mitigate against those risks. It will also discuss the importance of human oversight and trust in GenAI tools.

An introduction to the course

An introduction to the course

Listen to this audio clip in which Liz Hardie discusses some of the issues that will be considered in this course.

You can make notes in the box below.

Transcript

Discussion

Generative AI can be a fantastic tool but when it is misused it can have real world harmful consequences. You have already seen how a Generative AI image of Taylor Swift had the potential to influence the American elections in 2024.

The next section will start with a reminder of some of the concerns about using GenAI tools for legal advice and information, which was introduced in the first course in the series. This fifth course assumes you understand how GenAI and LLMs work: if you are not sure about this, we recommend you complete the first course Understanding Generative AI.

This is a self-paced course of around 180 minutes including a short quiz. We have divided the course into three sessions, so you do not need to complete the course in one go. You can do as much or as little as you like. If you pause you will be able to return to complete the course at a later date. Your answers to any activities will be saved for you.

Course sessions

The sessions are:

Session 1: Key concerns about using Generative AI – 45 minutes (Sections 1 and 2)

Session 2: Bias, societal and environmental concerns – 90 minutes (Sections 3, 4, 5 and 6)

Session 3: How to use Generative AI responsibly and ethically – 45 minutes (Sections 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11)

A digital badge and a course certificate are awarded upon completion. To receive these, you must complete all sections of the course and pass the course quiz.

Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

After completing this course, you will be able to:

Explain the ethical concerns about the use of Generative AI.

Identify ways to mitigate the ethical risks.

Understand the importance of human oversight and trust in Generative AI tools.

Glossary

Glossary

A glossary that covers all eight courses in this series is always available to you in the course menu on the left-hand side of this webpage.

Session 1: Key concerns about using Generative AI – 45 minutes

1 Using Generative AI ethically and responsibly

You will remember from the first course that GenAI tools are statistical probability tools trained on vast quantities of data and driven by powerful technology. They do not check the truth or validity of their outputs, and this has led to a number of concerns about their use. We introduced these in the first course Understanding Generative AI and will consider them further here.

GenAI tools being used unethically or irresponsibly

GenAI tools being used unethically or irresponsibly

From your study of the first course, or your knowledge from the general media about GenAI tools, what are some of the concerns which may lead to GenAI tools being used unethically or irresponsibly?

Discussion

There are a number of concerns about the use of GenAI tools (and other AI tools) including the risk of them producing incorrect or inaccurate outputs (also called hallucinations), their explainability, the digital divide, the deskilling of humans, legal implications, data protection issues, bias, ethical considerations and environmental concerns. This course will consider all of these in more detail. As the technology continues to develop at pace, you may have also identified other concerns which have developed since this course was written.

The next section will consider the first six of these concerns: hallucinations, inexplicability, digital poverty, deskilling, legal implications and data protection.

2 Some key concerns about Generative AI tools

This section will consider a number of concerns that are explored in greater detail in the first, second, sixth and seventh courses in the series.

Two of these are about the reliability and relevance of the outputs of GenAI tools (the risk of hallucinations and explainability) – two are about the potential legal consequences of using GenAI inappropriately (data privacy and legal implications) – while the final two are about the consequences of GenAI use on individuals (deskilling and the digital divide).

We will first look in slightly more detail at the risks relating to the output of the LLMs: hallucinations and explainability.

Hallucinations

As LLMs are predicting the next word in the sentence based on their training data, their responses can sometimes include errors or be nonsensical.

One of the classic examples of this is Google’s experimental ‘AI Overviews’ tool encouraging pizza-lovers to use non-toxic glue to make cheese stick to pizza better. A quick search online will let you find many other examples.

In the second course, Skills and strategies for using Generative AI, we learnt about some of the ways to use – or prompt – Large Language Models (LLMs) to try and ensure their outputs are relevant and as reliable as possible. Even using the clearest prompts possible however, there is a risk of incorrect or made-up information being produced.

Some errors are based on poor-quality training data, so there is not enough information on that topic in the training data for the tool to be able to predict with high accuracy the next words. These topics can be more prone to mistakes or errors, and this is the situation with legal queries at the time of writing this course.

Much of the information about the law is hidden behind paywalls and so the general LLMs have not been trained how to use it. This causes two different types of hallucinations: either the tool will make up a law or case, or it will include a relevant law or case in its answer but the content of that case or law does not relate to the legal query.

Listen to the following video from Harry Clark, a lawyer with Mishcon de Raya, who explains this further.

Transcript

Another problem with the legal information within the training data is that it is predominantly from the USA, and there is a lack of reliable and up-to-date information about English law. The tools can therefore make errors (for example, basing the answer on out-of-date law or the law relating to other countries). Sometimes this can be easy to identify, but due to the persuasive and authoritative tone of the LLMs it can sometimes be more difficult to identify these errors.

A 2024 study found that both generic LLMs and legal LLMs were prone to making errors when answering legal queries: ChatGPT only gave a complete and accurate answer in 49% of cases. The same study compared this to specific legal GenAI tools which are trained on the legal information found within the Lexis and Westlaw databases (and therefore behind the paywalls referred to above). Despite this, the study found Lexis+ only gave accurate and complete answers to the same set of legal queries 69% of the time, while Westlaw precision had an accuracy rating of 42% (Magesh et al., 2024).

As the tools get access to more legal data and are combined with reasoning tools, their accuracy may increase. However, the risk of errors is likely to be always present due to them working as a probability tool rather than a search engine or database.

Explainability

As you learnt in the first course, GenAI tools have access to so much training data, with complex and self-learning algorithms powering them, that it is difficult for us to understand why the tool has produced a particular output.

The neural networks underpinning GenAI tools can have many billions of parameters. It is therefore challenging for such tools themselves to explain how they have produced a given response to a prompt. This can make it difficult for a user to work out whether they can have confidence in the reliability and accuracy of the output.

There is ongoing research into explainable AI – in how to provide a clear reasoning to users as to why certain responses were produced – so the explainability of tools may become clearer over time.

This section will now consider two concerns that relate to the legal consequences of using GenAI outputs. These are also considered in more detail in the sixth and seventh courses.

Data privacy

The terms and conditions of some of these LLMs mean that any data you put into the tool can be used by the company as part of its ongoing training data sets. You may therefore effectively lose any copyright you had over those materials.

Some of the large volumes of data used to train the models are under copyright, and some were publicly posted but under certain usage conditions (in other words, only for use on a certain platform).

Nevertheless, this material was used within the training data of the tools, and there are a number of copyright court cases pending in different countries to establish whether the GenAI companies are liable for these breaches (for example, at the time of writing cases involving the BBC, Getty and Disney). It is unclear at the moment whether a user would be liable for breach of copyright if the output of a GenAI tool was substantially based on copyrighted material.

Finally, it is also not clear who legally owns the output of a GenAI tool. Many of the terms and conditions state that the output is owned by the user, but this may not be upheld by the courts if they are based on copyrighted materials or are very generic outputs.

Legal implications

The use of any prompts within the tools’ training data can also cause legal issues relating to data protection.

Inputting information by which a client can be identified will potentially breach professional responsibilities to keep client information confidential. There may also be breaches of data protection law if individuals have not consented to their information being shared in this way.

Finally, as with all technology, there are the risks of the system being hacked or held to ransom. The usual concerns about cybersecurity apply to GenAI as well as other IT systems – GenAI can also be used as a tool in more sophisticated cyber-attacks.

This section will now consider two concerns that relate to the consequences on individuals of using GenAI: the digital divide and deskilling (the former is considered in the fourth course, and the latter in the eighth course).

Digital divide

It has long been acknowledged that access and competency in using technology can lead to societal impacts, with those unable to make use of such technologies being disadvantaged.

New divides are likely to emerge surrounding GenAI. Currently, GenAI is predominantly being used in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic) countries, which have good Internet connectivity, and where English is widely understood. Most GenAI tools have been predominantly trained on material from these societies.

Some countries dominate the production of the technology needed for GenAI systems: more than 90% of the chips which analyse and process the data used by LLMs are designed and assembled in only a handful of countries: the United States, Taiwan, China, South Korea, and Japan (Giattino et al., 2024). These countries could therefore decide on the future development and evolution of AI technologies.

Exacerbating these issues, some GenAI tools have underlying political biases. DeepSeek, the Chinese-developed GenAI tool, refuses to discuss the events in Tiananmen square.

Even within the UK, there are individuals and communities who do not have access to digital tools such as GenAI due to poverty, a lack of skills, or their geographical location.

Deskilling

There are concerns that an increasing reliance and use of GenAI tools may lead to a lack of skills amongst individuals and workers.

This may affect the ability of people and organisations to evaluate and check the outputs of these tools, or to identify when a system has gone wrong or made an error (see the later section on the ‘human in the loop’).

It could also lead to an over-reliance on a small number of corporate entities to deliver key services.

Finally, it could limit the critical interpretation skills which are essential in the knowledge economy.

Risk and concerns

Risk and concerns

Next, we will consider one of the additional risks that Francine highlighted – the risk of bias within the tool and its outputs.

Session 2: Bias, societal and environmental concerns – 90 minutes

3 Bias

We discussed in the first course the age-old adage in computer science of “rubbish in, rubbish out”. Why is this relevant when discussing GenAI tools?

These tools have typically been developed by white, westernised, English-speaking men and the training data from the internet is typically produced by white, westernised, English-speaking men.

The outputs of GenAI tools therefore reflect the bias of the data the tools have been trained on. This bias can also be seen in the images depicting GenAI itself.

Images of Generative AI robots

Images of Generative AI robots

Use a general internet search engine and search for ‘images of generative-AI robots’. Are there any similarities in the results?

Discussion

When this search was done, at the time of writing the course, the robots were nearly all human-like with recognizable bodies. They were white and were predominantly male, such as the image below.

The same white humanoid robot figure also appears in films and TV series such as iRobot, Terminator, Artificial intelligence and Ex Machina.

The bias within GenAI tools can arise in two ways.

Firstly, bias can be due to the biases in the training data itself, which may reflect stereotypes, include discriminatory texts or be based on a limited range of materials that does not include diverse perspectives. For example, studies show that LLMs are prone to reinforce existing gender stereotypes with females being portrayed as warm and likeable, and males being portrayed as natural leaders and role models (Krook et al., 2024).

When considering picture generation, if the training data is not representative (such as ensuring balance between genders, age groups or ethnicity) this imbalance is often reflected the outputs.

One of the classic illustrations of this is to take a photo generation tool – such as DALL-E – and ask it to generate an image of a stereotypically gendered profession (nurses, judges). When asked to create an image of a lawyer, the person depicted is often young, male and white. This can be particularly worrying when using these tools for legal advice if the person needing advice is not white and male.

This bias is recognised and GenAI tools have created additional safeguards to ensure such requests produce less obviously biased outputs.

The other way bias can be produced in a GenAI output is due to the bias present in the algorithms that process the data. Most of the teams developing the tools and algorithms are not diverse, with a preponderance of white men. There is therefore often a lack of perspectives and viewpoints drawn from different experiences, which can weaken the product being developed. As a result, algorithms can be coded in a way that inadvertently favours certain outcomes or overlooks critical factors (Marr, 2024).

Why does this matter? Bernard Marr (2024) suggests that:

“The danger with AI is that it is designed to work at scale, making huge numbers of predictions based on vast amounts of data. Because of this, the effect of just a small amount of bias present in either the data or the algorithms can quickly be magnified exponentially.”

There have been a number of well-reported instances when bias in AI systems has led to harm. For example:

Amazon’s recruitment tool for software engineering roles discriminated against women – it had been trained on historic data from a time when fewer women applied and so there was less data available to properly assess applications from women (Reuters, 2018).

Facial recognition systems struggle to identify those from an ethnic minority and have been banned from the EU (Amnesty International, 2023).

COMPAS, a tool used within the USA to assess the risk of convicted criminals reoffending, was found to overestimate the risk of reoffending by black people (ProPublica, 2016).

Within the legal context, it is important that GenAI users are aware of the risk of bias in the outputs, and evaluate and assess whether the outputs should be used. This is particularly relevant when advising those who come from historically disadvantaged groups within the justice system, such as Black people, those from ethnic minorities, women and those with disabilities.

Having considered possible bias which may cause harm to individuals when using GenAI, in the next section we will consider some broader societal concerns.

4 Societal concerns

At the start of this course, we discussed an example of an image generated by AI which was shared on social media to wrongly suggest Taylor Swift supported Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. This is an example of some of the broader societal concerns around the use of GenAI.

Deepfakes involve the use of GenAI tools to mimic someone’s image or voice in a way that appears real. Whilst this can be fun, it potentially has frightening consequences if the image of a world leader or company owner is used to spread wrong information, or the deepfake is used to de-fraud individuals.

Whilst it has been possible to generate these fakes for some time, the advances in GenAI now means that these deepfakes can be done much more easily, cheaply, quickly and with very little original data (a photo or short audio clip is now sufficient to train the GenAI tool). The speed of these changes and the improvement in the quality of both images and text is remarkable (Giattino et al., 2024) but could be harmful if used for misinformation or phishing.

Ofcom research from 2024 revealed that two in five people say they have seen at least one deepfake in the last six months, and this typically involves the generation of sexual content and scam adverts (Ofcom 2024).

Listen to this video of Harry Clark, a lawyer with Mishcon de Reya, discussing the importance of verifying information in a GenAI era.

Transcript

There are also concerns that GenAI tools can be used in a way they were not envisaged originally, sometimes in a harmful way. For example, could GenAI meeting summarisation software, or GenAI facial recognition software, potentially be used for surveillance by companies or governments (Olvera, 2024; Pfau, 2024)?

Finally, GenAI systems are labour intensive and use low-paid workers in the Global South to work through some of the training data used, tagging a vast number of examples of racist, sexist, or violent language. This has allowed the tool to identify inappropriate content and implement guardrails (discussed in the first course). For example, OpenAI reportedly used workers from Kenya to go through such material, paying $2 an hour (Time, 2023).

Whilst these concerns may not directly impact you, your clients or your organisation, it is important when using AI tools to inform yourself of the societal concerns surrounding both the development of the tool, and how it can be misused. You will then be able to make choices that minimise harm to others and to society.

As well as being labour intensive, the development of GenAI tools is also resource intensive. The next section discusses the final ethical concern about GenAI use, which is the impact such tools have on the environment.

5 Environmental impact

As discussed in the first course, GenAI tools rely on data centres which require vast amounts of energy and water to work. At a time when many organisations are looking to reduce their carbon footprint, and countries are working towards net zero, the environmental impact of the increasing use of GenAI tools is problematic.

The energy demands of GenAI are so high that Microsoft has taken out a 20-year contract to use energy from the nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island. The 2024 AI Trends report (So, 2024) raised concerns that the demand for power from these companies is outpacing the ability of utilities to expand capacity. The resulting energy gap could become a bottleneck and limit the growth of AI and other power-intensive applications.

In addition to energy use, computers also produce heat – and data centres produce a lot of heat. Water is commonly used to transfer that heat out of the centre. An average hyperscale data centre, such as those used for training AI models, uses around 550,000 gallons (2.1 million litres) of water daily. This is especially concerning considering that these data centres are often located in areas with limited water supply. One estimate suggests that by 2027 the cooling demands of AI would be more than half the total annual water consumption of the United Kingdom.

However, it can be difficult to get accurate or complete data on environmental impacts as precise numbers are closely guarded by tech companies and are often under-documented.

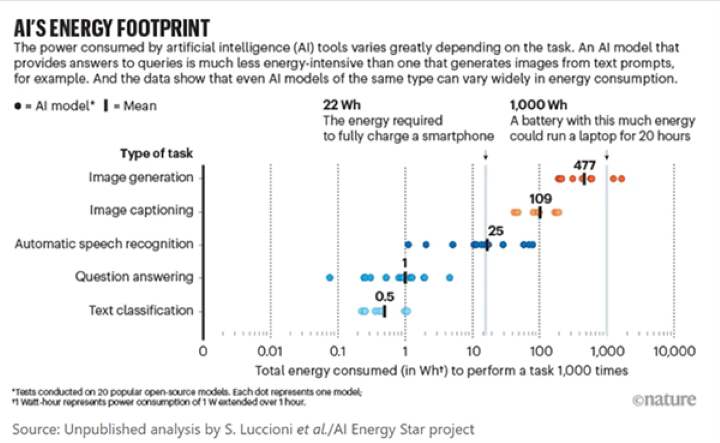

When using a GenAI tool, there is also a difference in energy consumption depending on the task. In general, supervised tasks such as question answering or text classification – in which models are provided with a set of options to choose from or a document that contains the answer – are much more energy efficient than generative tasks that rely on the patterns learnt from the training data to produce a response from scratch (Luccioni et al., 2024). In addition, the energy required for image generation is considerably higher than that needed for question answering.

So, what can individuals do to reduce the environmental impact of using GenAI tools? As different types of AI vary in their environmental footprint, choosing the right tool for the task will minimise the environmental impact and energy costs.

Do you know the environmental impact of using GenAI tools?

Do you know the environmental impact of using GenAI tools?

Answer the three questions below.

a.

The same as turning on an LED lightbulb for five minutes

b.

The same as boiling a kettle

c.

The same as using a hairdryer for five minutes

The correct answer is b.

a.

20 times

b.

40 times

c.

60 times

The correct answer is c.

a.

The same as fully charging your smart phone

b.

The same as using a hairdryer for five minutes

c.

The same as boiling a kettle

The correct answer is a.

The image below shows the total power consumed by different AI tools when completing different tasks.

Generally, using a general internet search engine instead of GenAI is much more energy efficient. Individuals should therefore ask themselves if they need to use GenAI for the task or whether other tools would work as well and be less energy intensive.

As well as thinking carefully about the right tool for the task, crafting effective AI prompts can minimise unnecessary prompting and reduce environmental impact. If you have not already done so, you may want to look at the second course, Skills and strategies for using Generative AI.

Having explored a range of different ethical concerns regarding GenAI use, the next section will now consider why this is important for individuals and organisations.

6 Why is this important?

So what? As you learnt about the different ethical concerns in the previous sections of this course, hopefully you have already started to think about why it is important to be aware of these issues when using GenAI.

As well as an individual being disadvantaged due to a wrong, misleading or offensive output, law firms and organisations can also be harmed by an inappropriate use of GenAI.

Harms caused by an unethical or irresponsible use of a GenAI tool

Harms caused by an unethical or irresponsible use of a GenAI tool

a.

This could affect the individual user.

b.

This could affect a law firm or other organisation.

c.

This could affect both.

The correct answer is c.

Comment

The Solicitors Regulation Authority is concerned that individuals using GenAI risk relying on hallucinations or wrong information and, therefore, will not be able to get a legal remedy for their problem (Solicitors Regulation Authority, 2023). There is also the risk that court cases involving inaccurate GenAI information will take longer to resolve, which may increase the delays faced by individuals in getting a court hearing. For organisations, relying on wrong information generated by AI will damage their reputation, potentially leading to negligence claims against them and, if court proceedings are issued, allegations of misleading the court and possibly wasted cost orders to compensate the other party for the costs they have incurred.

a.

This could affect the individual user.

b.

This could affect a law firm or other organisation.

c.

This could affect both.

The correct answer is b.

Comment

This type of deepfake can damage the organisation’s reputation, and lead to a loss of clients and potentially revenue. It could also cause concern and upset amongst the employees of the organisation.

a.

This could affect the individual user.

b.

This could affect a law firm or other organisation.

c.

This could affect both.

The correct answer is b.

Comment

If this information is made public, it risks the reputation of the company and adverse comments being made by clients and employees – particularly if the company has committed to reducing its carbon footprint or it champions environmental causes.

a.

This could affect the individual user.

b.

This could affect a law firm or other organisation.

c.

This could affect both.

The correct answer is b.

Discussion

This may reflect the bias within the GenAI tool, but in using the video the organisation risks reputational damage, adverse comment and being unable to recruit diverse employees or clients.

a.

This could affect the individual user.

b.

This could affect a law firm or other organisation.

c.

This could affect both.

The correct answer is c.

Comment

Depending on the contractual terms of the LLM, if the information can form part of the training data, the adviser has potentially breached their professional responsibilities to keep their client’s information confidential. For the organisation, there may be breaches of data protection law, they may face consequences from the regulators, and there may also be a risk of a security breach. This type of scenario is more common than you might expect: a recent study of over 10,000 employees found that 15 percent of employees input company data into ChatGPT (Responsible Artificial Intelligence Organisation, 2024).

a.

This could affect the individual user.

b.

This could affect a law firm or other organisation.

c.

This could affect both.

The correct answer is a.

Comment

Where GenAI tools are only trained on information from certain groups, it can lead to unfair and unrepresentative outcomes as in this example. If the client can prove bias, they may have a case for discrimination.

a.

This could affect the individual user.

b.

This could affect a law firm or other organisation.

c.

This could affect both.

The correct answer is a.

Comment

The text in the blog appears to be copyrighted, and so there may be legal consequences of publishing it without the correct licence. This could also cause the individual reputational damage.

a.

This could affect the individual user.

b.

This could affect a law firm or other organisation.

c.

This could affect both.

The correct answer is b.

Discussion

Potentially there could be data protection concerns if the system was not secure or was not able to protect the client’s personal information. It could cause reputational damage if the tool did not work as expected, or the organisation was unable to explain how it came to its decisions. Finally, the organisation could lose clients if they did not have access to the internet due to digital poverty or exclusion, or did not trust GenAI systems.

This activity has shown that using GenAI tools without thinking of the ethical implications can lead to harm to both individuals and organisations. The next section suggests some best practices to use GenAI ethically and responsibly.

Session 3: How to use GenAI responsibly and ethically – 45 minutes

7 Best practice for using Generative AI ethically and responsibly

A number of guidance documents have been developed to help organisations mitigate the risks and concerns described in this course and use GenAI ethically and responsibly. Some of this guidance is listed below.

However, in general there are four main principles which underpin the guidance offered.

Click on each of the tiles below to learn more.

Professional standards

Professional standards

Further reading

Further reading

If you are interested in finding out more about GenAI guidance, you can also look at the following documents:

Government Digital Service – Artificial Intelligence Playbook for the UK Government (HTML).

USA guidance to the American Bar – ABA Ethics Opinion on Generative AI Offers Useful Framework.

Australian guidance for solicitors – A solicitor’s guide to responsible use of artificial intelligence.

Indian guidance – India’s Advance on AI Regulation.

This is a rapidly developing area. Since this course was written there may be other guidance and policies published that are relevant, for example by the government, professional regulators or other organisations.

Ethical and responsible use of Generative AI principles and guidance

Ethical and responsible use of Generative AI principles and guidance

Using a general internet search engine, carry out a search for ‘ethical and responsible use of Generative AI principles and guidance’. You may need to narrow your search by including terms such as ‘UK government’ ‘Law Society’ or ‘Solicitors Regulation Authority’.

Has any new guidance been issued? If so, read the guidance. Does it include anything new, or change any of the suggestions you already have made?

Discussion

In light of the rapid changes in technology and regulation in this area, you may need to repeat this exercise every year to ensure that both you and your organisation are complying with relevant regulators’ guidance and best practice.

Having considered some of the ways in which organisations can mitigate against the ethical risks presented by GenAI, this course will now consider one of the most important suggestions: the human in the loop.

8 Human in the loop

Another important safeguard to ensure the ethical and responsible use of GenAI tools is the concept of the ‘human in the loop’. This refers to the importance of having an individual responsible for reviewing the outputs of GenAI, overseeing the system and checking the output is correct.

The Nuffield Family Justice Observatory’s briefing paper on ‘AI in the family justice system’ (Saied-Tessier, 2024) recognised the importance of the human in the loop (HITL), defining it as being where “humans are directly involved in the system’s decision-making process. HITL is often used in situations where human judgement and expertise are crucial, and AI is used as a tool to assist human decision-making”.

Human in the loop requires that there is human oversight when GenAI systems are designed, developed and used. When using GenAI in legal contexts, for example, this would involve a person with legal expertise checking the outputs of an LLM to ensure it is accurate and does not include hallucinated, incorrect or biased results before it is used or relied on.

In particular, the human in the loop in a legal context would need to check the law was accurately stated, up-to-date and there were no relevant omissions; any cases or statutes referred to were real and related to the legal arguments being put forward; and that any legal arguments were evidenced and logical. You will find out more about AI literacy in the eighth course Preparing for tomorrow: horizon scanning and AI literacy.

A human in the loop addresses ethical concerns

A human in the loop addresses ethical concerns

a.

Bias

b.

Data protection issues

c.

Deskilling of humans

d.

Digital divide

e.

Environmental concerns.

f.

Explainability

g.

Hallucinations

h.

Legal implications

i.

Societal considerations such as deepfakes

The correct answers are a, b, g, h and i.

Discussion

Human in the loop can help address some, though not all, of these concerns. It would potentially identify the concerns identified above so they could be amended and rectified.

The idea of a human in the loop is endorsed by the Law Society (2024), whose GenAI guidance states:

“Even if outputs are derived from Generative AI tools, this does not absolve you of legal responsibility or liability if the results are incorrect or unfavourable. You remain subject to the same professional conduct rules if the requisite standards are not met…You should…carefully fact check its products and authenticate the outputs.”

Having considered some of the ways in which organisations and individuals can mitigate against the ethical concerns identified in this course, the next section discusses the legal consequences of using GenAI unethically or irresponsibly.

Further reading

Further reading

If you are interested, you can learn more about how important human skills are in this supplementary course content – The importance of human skills.

9 Legal liability for Generative AI use

What rights do users have if a GenAI tool provides inaccurate legal advice?

This section considers whether it is possible to hold the owners of the GenAI tools responsible for inaccurate legal advice, and the responsibility of organisations using these tools.

At the time of writing, it is unclear who would have liability for any harm caused by relying on inaccurate legal advice produced by a GenAI tool. The terms and conditions of LLMs which have been made freely available typically seek to pass on both liability and risk for using the tool to the user.

Since court cases were issued seeking compensation for breach of copyright related to the training materials of LLMs, the companies have offered indemnities to users. However, typically this only applies to commercial paying users and they are restricted and often subject to a cap.

For example, Microsoft has announced its Copilot Copyright Commitment, through which it pledges to assume responsibility for potential legal risks involved in using Microsoft’s Copilot services and the output they generate. If a third party were to bring a claim against a commercial customer of Copilot for copyright infringements for the use and distribution of its output, Microsoft has committed to defending the claim and covering any corresponding liabilities. (De Freitas and Costello, 2024)

It is unclear whether a case could be brought against the owners of a GenAI tool for inaccurate advice or harm caused by a biased decision. It is also important for individuals to be aware that technological companies offering GenAI legal advice are usually not regulated by the Law Society. This means that there is no access to compensation schemes for inaccurate advice obtained directly from the tools. The company is also not covered by legal professional rules such as client confidentiality or the duty to act in the best interests of the client.

By contrast, the legal organisations using GenAI tools may be liable for any harm caused by their unethical or irresponsible use. In providing services to clients, organisations have a duty of care towards them and may be liable in negligence for inaccurate advice, if it was foreseeable that relying on it uncritically could lead to harm.

GenAI guidelines by the Law Society, Bar Council and Judicial Guidance all stress the need to check the accuracy of outputs from an LLM. The guidance also confirms that the responsibility for what is presented to court and to clients remains with the legal adviser, even if it originates from a GenAI tool.

Given the likelihood that organisations will be held liable for any harm caused by the irresponsible use of GenAI, it is important that organisations put in place processes to evaluate the workings of GenAI tools such as ‘Human in the Loop’ and / or the adoption of an Ethical use framework. The third course, Key considerations for successful Generative AI adoption, also looks at how organisations can successfully use GenAI.

Finally, in the next section, this course considers whether the public trusts GenAI tools, and the implications this has for the ethical and responsible use of GenAI.

10 Building trust in Generative AI

For an organisation or individual planning to use a GenAI tool, it’s important to understand how other people will respond to its operation and the outputs it produces.

The trust employees and clients place in GenAI will affect how and when an organisation plans to use such tools. It is important to note however that this is a rapidly developing area, and the public’s trust in GenAI systems may well develop and increase, as the use of such tools becomes more familiar and frequent within society.

Current surveys suggest that the older generations are less likely to trust GenAI, with two thirds of those not using GenAI being born before 1980. By contrast, Gen Z (those born after 1995), who have grown up with technology, are most likely to use and trust GenAI (Koetsier, 2023). One consequence is that supervisors, managers and owners of organisations may not be aware of the extent of their employees’ use of GenAI tools.

For example, did you know that a 2024 survey of 4,500 employees and managers found that over half of Gen Z employees trusted GenAI more than their managers? The same survey suggested that employees’ expectations around GenAI use within work was not matched by their managers, with over half of Gen Z employees also expressing concerns about inadequate organisational guidelines (Khan, 2024). While these employees are more likely to trust GenAI and be confident in using it, they do so uncritically and are less likely to understand the tools’ limitations (Merrian and Saiz, 2024).

Organisations therefore need clear guidance on the responsible and ethical use of GenAI for employees and to ensure that they understand the limitations and risks of inappropriate use.

When considering client trust in GenAI, this will depend on their age, background and familiarity with GenAI tools. Businesses, older clients or clients who are unfamiliar with GenAI may need reassurances before trusting the use of GenAI tools for legal advice. They are likely to be concerned about data privacy, the accuracy of any outputs, and potential bias in outputs (Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2024).

Addressing these issues through a responsible and ethical use policy will encourage the client’s trust in the use of these tools. Simply not using these tools can also have consequences, in terms of reduced efficiency, increased expense and societal concerns. For example, the UN warns of the potential of widening digital divides if individuals and businesses fail to take advantage of GenAI due to a lack of trust (United Nations, 2024).

By contrast, individual clients (particularly if they are younger) are more likely to trust GenAI and adopt any output uncritically. An interesting study by Southampton University found that when offered advice written by a lawyer and by a GenAI tool, members of the public were more likely to choose to believe the GenAI tool. This remained true even when they knew the advice was from a GenAI tool (Schneiders et al., 2024). One possible reason may be the over-confident tone of advice produced by an LLM, which typically will not include the caveats and disclaimers likely to be included by lawyers.

Given these concerns, it is important that outputs of GenAI tools are evaluated before being released to clients, and that organisations and individuals are transparent in reporting when GenAI has been used, and outputs are being included in client communication.

How do you ensure your ethical and responsible use of GenAI?

How do you ensure your ethical and responsible use of GenAI?

Are your clients sceptical, or overconfident, when using GenAI tools? In light of the trust that they have (or do not have) in GenAI, what do you need to do to ensure your ethical and responsible use of GenAI (or that of your organisation)?

Make a note of this below and also in your work folders to ensure you address any identified issues in your GenAI guidance.

11 Conclusion

Having studied this course, you now know more about the ethical challenges posed by GenAI use and the harm that can be caused by its unethical and irresponsible use.

The course has outlined some of the ways in which individuals and organisations can identify ethical risks and mitigate against them, including the importance of ensuring there is a human in the loop and appropriate guidance.

If you are considering using GenAI in your organisation, we suggest you look at the sixth course, Navigating risk management.

For individuals interested in finding out more about using GenAI, we would recommend the eighth course which considers the future of GenAI: Preparing for tomorrow: horizon scanning and AI literacy.

Moving on

When you are ready, you can move on to the Course 5 quiz.

Website links

ABA – ABA Ethics Opinion on Generative AI Offers Useful Framework

Bar Council – New guidance on Generative AI for the Bar

BBC News – Glue pizza and eat rocks: Google AI search errors go viral

BBC News – Is China's AI tool DeepSeek as good as it seems?

Carnegie India – India’sh Advance on AI Regulation

Courts and tribunal judiciary – Artificial Intelligence (AI) – Judicial Guidance

Dgtl Infra – Data Center Water Usage: A Comprehensive Guide

Google – AI Overviews and your website

Government Digital Service – Artificial Intelligence Playbook for the UK Government (HTML)

Law Society – Generative AI: the essentials

LSJ Online – A solicitor’s guide to responsible use of artificial intelligence

TechTarget – 12 top resources to build an ethical AI framework

References

Amnesty International (2023) EU: European Parliament adopts ban on facial recognition but leaves migrants, refugees and asylum seekers at risk. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/06/eu-european-parliament-adopts-ban-on-facial-recognition-but-leaves-migrants-refugees-and-asylum-seekers-at-risk/ (Accessed 18 March 2025).

De Freitas, I. and Costello, E. (2023) ‘Exploring AI indemnities: their purpose and impact’, Farrar & Co., (3 October). Available at: https://www.farrer.co.uk/news-and-insights/exploring-ai-indemnities-their-purpose-and-impact/ (Accessed 19 March 2025).

Giattino, C., Mathieu, E., Samborska, V. and Roser, M. (2023) ‘Artificial Intelligence’, Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/artificial-intelligence (Accessed 17 March 2025).

Khan, Z. (2024) ‘Gen Z professionals trust GenAI more than their 'biased managers': Study’, Business Standard, (25 November). Available at: https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/gen-z-professionals-trust-genai-more-than-their-biased-managers-study-124112500889_1.html (Accessed 19 March 2025).

Koetsier, J. (2023) ‘Generative AI Generation Gap: 70% Of Gen Z Use It While Gen X, Boomers Don’t Get It’, Forbes , (9 September). Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2023/09/09/generative-ai-generation-gap-70-of-gen-z-use-it-while-gen-x-boomers-dont-get-it/ (Accessed 21 March 2025).

Krook, J., Schneiders, E., Seabrooke, T., Leesakul, N. and Clos, J. (2024) Large Language Models (LLMs) for Legal Advice: A Scoping Review (4 October). Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4976189 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4976189 (Accessed 17 March 2025).

Larsen, J, Mattu, S, Kirchner, L. and Angwin, J. (2016) ‘How We Analyzed the COMPAS Recidivism Algorithm’, ProPublica, (23 May). Available at: https://www.propublica.org/article/how-we-analyzed-the-compas-recidivism-algorithm (Accessed 18 March 2025).

The Law Society (2024) Generative AI: the essentials. Available at: https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/topics/ai-and-lawtech/generative-ai-the-essentials (Accessed 19 March 2025).

Luccioni, A. S., Jernite, Y. and Strubell, E. (in process) (2024) ACM Conference: Fairness, Accountability and Transparency [prepublication]. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-02680-3 (Accessed 17 March 2025).

Magesh, V., Surani, F. and Dahl, M. et al. (2024) Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools [prepublication]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2405.20362 (Accessed 17 March 2025).

Merrian, M. and Saiz, B. S. (2024) ‘How can we upskill Gen Z as fast as we train AI?’, Ernst & Young , (10 December). Available at: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/about-us/corporate-responsibility/how-can-we-upskill-gen-z-as-fast-as-we-train-ai (Accessed 17 March 2025).

Marr, B. (2024) ‘Building Responsible AI: How to Combat Bias and Promote Equity’, Bernard Marr & Co., (3 June). Available at: https://bernardmarr.com/building-responsible-ai-how-to-combat-bias-and-promote-equity/ (Accessed 18 March 2025).

Ofcom (2024) A deep dive into deepfakes that demean, defraud and disinform. Available at https://www.ofcom.org.uk/online-safety/illegal-and-harmful-content/deepfakes-demean-defraud-disinform (Accessed 27 June 2025).

Olvera, A. (2024) ‘How AI surveillance threatens democracy everywhere’, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (7 June). Available at: https://thebulletin.org/2024/06/how-ai-surveillance-threatens-democracy-everywhere/ (Accessed 18 March 2025).

Pfau, M. (2024) ‘Artificial Intelligence: The New Eyes of Surveillance’, Forbes, (2 Feb). Available at: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil/2024/02/02/artificial-intelligence-the-new-eyes-of-surveillance/ (Accessed 18 March 2025).

Price Waterhouse Coopers (2024) Risk Register: Principal risks and responses. Available at: https://www.pwc.co.uk/who-we-are/annual-report/principal-risks-and-responses.html (Accessed 20 March 2025).

Responsible Artificial Intelligence Institute (2024) Unlock the Power of Responsible Generative AI in Your Organization. Available at: https://www.responsible.ai/best-practices-in-generative-ai-guide/ (Accessed 19 March 2025).

Reuters (Dastin, J.) (2018) Insight - Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight-idUSKCN1MK08G/ (Accessed 18 March 2025).

So, K. (2024) ‘AI Trends 2024: Power laws and agents’, Generational, (13 December). Available at: https://www.generational.pub/p/ai-trends-2024 (Accessed 19 March 2025).

Saied-Tessier, A. (2024) ‘Artificial intelligence in the family justice system’, [Briefing] Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. Available at: https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/news/briefing-paper-ai-in-the-family-justice-system (Accessed 19 March 2025).

Schneiders, E., Seabrooke, T., Krook, J., Hyde, R., Leesakul, N., Clos, J and Fischer, J. (2024) Objection Overruled! Lay People can Distinguish Large Language Models from Lawyers, but still Favour Advice from an LLM. Available at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2409.07871 (Accessed 17 March 2025).

Solicitors Regulation Authority (2023) Risk Outlook report: The use of artificial intelligence in the legal market. Available at: https://www.sra.org.uk/sra/research-publications/artificial-intelligence-legal-market/ (Accessed 20 March 2025).

Time (Perrigo, B.) (2023) Exclusive: OpenAI Used Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour to Make ChatGPT Less Toxic. Available at: https://time.com/6247678/openai-chatgpt-kenya-workers/ (Accessed 18 March 2025).

United Nations (2024) Governing Ai for Humanity final report. Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4062495?v=pdf (Accessed 17 March 2025).

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Important: *** against any of the acknowledgements below means that the wording has been dictated by the rights holder/publisher, and cannot be changed.

554801: Summit Art Creations / Shutterstock

554683: Evan El-Amin / shutterstock

554685: Brian Friedman / shutterstock

554692: Quote from Taylor Swift's Instagram account on NBC News (2024) 'Taylor Swift endorses Kamala Harris after presidential debate' www.nbcnews.com/. Available from https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2024-election/taylor-swift-endorses-kamala-harris-rcna170547 [Accessed 9/5/25]

554774: Suri_Studio / Shutterstock

553070: mongmong_Studio / shutterstock

553087: zum rotul / Shutterstock

553085: Graphic Depend / Shutterstock

553079: FAHMI98 / Shutterstock

553089: vectorwin / Shutterstock

553090: Yossakorn Kaewwannarat / Shutterstock

553073: Bakhtiar Zein / shutterstock

554908: Created by OU artworker using OpenAI (2025) DALL-E3

553086: Jerome / Alamy Stock Photo

553076: Red Vector / Shutterstock

554954: Taken from Sasha Luccioni, Boris Gamazaychikov, Sara Hooker, Régis Pierrard, Emma Strubell, Yacine Jernite & Carole-Jean Wu (2024) 'Light bulbs have energy ratings so why cant AI chatbots?' Nature.com (Available from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-02680-3 [Accessed 22/05/25)

554987: RealPeopleStudio / shutterstock

555130: mikkelwilliam / Getty

555141: Boygointer | Dreamstime.com

555277: Matthias Ziegler| Dreamstime.com