Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 10:18 PM

Unit 2 – Working towards healing

Introduction

You will begin this unit by reading a poem written by a poet who fled Syria as a child, taking tiny precious things that would remind him of home and using these smells and textures to soothe him at a time when he faced hostility and fear while being displaced.

This poem highlights the anti-refugee hostility that many people face while being displaced but also sheds light on the small things that can help a person to heal like a certain smell, a certain memory or a certain item they carry with them.

In this unit, you will explore two approaches that you can use to appropriately support your students on their healing journey – trauma-informed care and identity-informed approaches. You will also explore psychosocial support and how certain strategies can be implemented in school to support all students and staff.

As you complete Unit 2, you will review several useful tools and resources to take away and use in your daily work. You will also learn about relevant frameworks and activities to help you use trauma and identity informed approaches in your work.

Finally, you will work through a short case study to try to implement some of the strategies you have covered.

Unit 2 Objectives

Unit 2 Objectives

- Explain the impacts of utilising trauma-informed approaches and identity-informed approaches.

- Identify ways that people can heal using individual or collective healing strategies.

- Formulate psychosocial support strategies to enable healing within school.

Poem – My Hazara people by Shukria Rezaei

In her poem, Shukria Rezaei explores the importance of identity when exploring an individual’s trauma.

Many refugees flee war and physical violence which is putting them in danger, but many face overlapping issues such as xenophobia, racism, ethnic cleansing as well as war.

Shukria wrote this poem when she was 15 years old.

As in Unit 1, you have the option to listen to the poem if you prefer. Or why not read and listen at the same time?

Transcript

These audio poems are a great resource to use in class.

In this unit, we will explore trauma-informed approaches with a detailed examination of identity and how this can impact a person’s experience of trauma and their route to healing.

Culture is a significant part of every person’s identity including music, food, crafts, beliefs and knowledge. Our senses can provide powerful moments of grounding and healing such as listening to a song from back home, smelling our favourite dish and working on a traditional craft we learnt as a child.

We often consider smells, sounds and images to be potential triggers when working with displaced children and youth. These can also be a part of the healing process. Sensory boxes can be a wonderful way for students to get back to a state of calm. They can be filled with sensory toys, scented objects, postcards, and nature (for example, leaves, stones or sticks) and can be useful for students of all ages.

In the next task, you will create a sensory box for yourself.

Take a quick moment to imagine what you would have taken with you to remind you of home if you were in Shukria’s situation.

Sensory boxes are a useful tool that can be used for mindfulness and grounding but can also be linked to academic tasks. For example, taking an item from the sensory box as a prompt for a story. If you are looking for ways to use sensory boxes in your classroom, in your own time, you may want to read the article, Using Sensory Experiences to Support Elementary Students.

When creating activities, building lesson plans and considering resources to use in lessons, it is important to work through a trauma-informed lens to minimise the chance of retraumatising children, make them feel safe and respected and to take chances to rebuild trusting relationships.

Trauma-informed care

What is a trauma-informed approach to education?

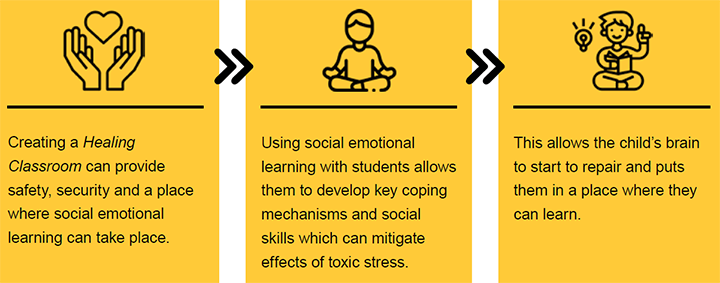

Trauma-informed care is an approach that recognises the widespread impacts of trauma on an individual’s life. It focuses on creating safe and supportive environments in order to avoid re-traumatisation. Schools are ideal places to implement trauma-informed care as they are already intended to be places aiming to nurture, support and guide children and youth.

Trauma-informed care is an assets-based approach which guides educators to focus on students’ strengths, rather than focusing on the challenges they may currently be facing (e.g., learning a new language, potentially struggling with trauma and cultural bereavement).

Trauma-informed care in education instead focuses on the existing knowledge and skills an individual brings with them into the classroom and utilises these as a route to healing.

Why is it needed in schools?

Trauma impacts individuals in numerous ways. One major impact is that it can block a child’s ability to focus and to learn. If students attend a school where the staff are not trauma-informed and the school is not set up as a safe space for people recovering from trauma, they will struggle to thrive.

Trauma-informed care is proven to improve educational outcomes, reduce problematic behaviours and improve feelings of self-worth for individuals to help them on their journey to healing.

Children and youth who have experienced war, danger and forced displacement need a safe place to land when they arrive in the UK. They need trauma-informed schools and staff to collaborate with them to help them resettle, rebuild, heal and learn.

How can it benefit students and teachers?

Trauma-informed care within education helps create safe learning environments and has been proven to result in improved student attendance, engagement and academic performance. It also has a huge impact on reducing behavioural issues and helps schools to find better ways to support students to stay in education and avoid exclusions.

This approach focuses on positive behaviour management through relationship building, goal setting and working in partnership with students rather than using shouting, exclusions, detentions and other common tools which may re-traumatise students and make them see school as a threatening place where they are unwelcome. Trauma-informed schools are happier more respectful places for everybody.

Explore ready-made tools from the National Education Union for transforming your school into a trauma-informed setting in this dedicated toolkit.

Trauma-informed settings focus on the six key principles of trauma-informed care.

Click on each tile below to learn more.

Look at the table below which explores potential past traumatic events, the likely impacts of these on students and strategies schools can utilise to work with these students in a trauma-informed way:

| What has the student experienced? | What is the likely impact of this? | Principles of trauma-informed care. Which TIC principle can support this student? | Example of school strategy. What does this principle look like in practice? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Killings, injury threat, disappearances. | Chronic fear, hypervigilance. | Safety. | Visual timetable with clear timings, warnings before fire alarms, introduce staff and roles. |

| Oppression, secrecy. | Unable to trust, destruction of core beliefs. | Trust and transparency. | Expectations, procedures and policies explained to families. Honest communication at all times. |

| Death of loved one, separation, forced displacement. | Breaking of bonds, loss of community. | Peer support. | Buddy schemes, staff mentors, group work, extra-curricular activities, games. |

| Oppression, impossible choices, human rights violations. | Powerlessness, unable to trust. | Collaboration and mutuality. | Regular, accessible communication with families, bilingual homework, translanguaging. |

| Human rights violations, oppression, lack of choice, impossible choices, helplessness. | Loss of agency, helplessness, humiliation, degradation, powerlessness. | Empowerment, voice and choice. | Student-led goal setting, student and family involved in key choices. Use culturally responsive pedagogy. Use culturally responsive pedagogy. |

| Discrimination, invasion, occupation. | Humiliation, powerlessness, unable to trust. | Cultural, historical and gender issues. | Ensure basic religious, cultural and gender needs are met (e.g., halal food, prayer spaces). Use culturally responsive pedagogy. |

In Units 3–5, you will review the strategies above in greater detail as part of the Healing Classrooms 3-step programme.

Risk and protective factors

It’s important to note that not all children who are refugees will be traumatised by their experiences of conflict, displacement or resettlement and that no two people will experience traumatic events in the same way.

Schools can be excellent places to provide sanctuary to students who have endured conflict and displacement. They can also be places where trauma is worsened.

The following table shows common risk and protective factors for you to consider when welcoming refugee students.

| Risk factors | Protective factors |

|---|---|

Lack of adequate language support:

| Opportunities for relationship building:

|

Limited support during transition:

| Engaging parents/caregivers:

|

Punishment-based behaviour management:

| Programmes to suit students’ needs:

|

Environments which are not inclusive:

| Use of interpreters. If children are able to communicate their needs, schools will be able to meet them:

|

Lack of adequate anti-bullying procedures:

| Continued support responsive to needs:

|

When making policy, teaching and interacting with students, always remember to work in line with these principles so as to not retraumatise a student accidentally. Ensure these are utilised when working with parents and families too, keeping in mind that parents have not only experienced these things themselves but had to protect their children from them simultaneously.

To provide more insights into what trauma-informed care can look like in the classroom, you may watch the following video.

To ensure trauma-informed care is implemented properly, ensure these principles are used to guide policy, programming and individual behaviour. Above all, school staff must ensure that they do no harm.

You must never push a child to share what happened to them or expect them to have the same response as another child with similar traumatic experiences. Singling out students for their behaviour can also seem very threatening to them.

Next, you will complete a task reviewing three scenarios and adapting them to ensure they follow the six principles of trauma-informed care.

Task 5: Responding in a trauma-informed approach

Task 5: Responding in a trauma-informed approach

Using the six principles of trauma-informed care, how could you respond to the situations below in a trauma-informed way?

Read the first example and then complete your own responses to the second and third examples in the text boxes below.

| NOT trauma-informed | Trauma-informed approach |

| “Everybody else is in their seats and again we’re waiting on YOU to listen!” | I would take time to sit with the student and decide on appropriate classroom behaviour together is a way of involving mutual collaboration. Involving the student in the process and discussing why we should behave this way can help get more buy-in from the student and help build rapport by showing I am a trusted adult who is honest and transparent with them. |

| “Ayesha has also come from Syria and she’s not using it as an excuse to misbehave.” | |

| “He won’t share anything about what happened to him in Afghanistan so how can I figure out how to help him?” |

Comment

No matter the situation or your needs as educators or as schools, you must always ensure that you do no harm.

The task may have helped you to consider other ways you can manage behaviour using positive classroom management, the clean slate approach and collaborative rulemaking as a class.

You will cover these in Units 3–5 as you complete more tasks and reflections using the recommended Healing Classrooms strategies.

Healing Classrooms is an example of trauma-informed care.

Next, you will learn about identity-informed approaches to healing.

Identity-informed approaches are an integral part of trauma-informed care and are especially important when working with people who have a culture different to your own.

All of the Healing Classrooms strategies are based upon trauma-informed and identity-informed approaches to reduce the chance of retraumatisation and to put the specific needs of refugee students at the centre of your work.

Identity-informed approach

In this section you will focus on a key area of trauma-informed care – identity-informed approaches to trauma recovery. This is a vital part of trauma-informed care to focus on, especially when working with students from cultures, races and religions different to your own.

An identity-informed approach is very much a part of trauma-informed care and is essential when working with people from cultures different to your own, to ensure you are working in a culturally appropriate and trauma-informed way with all students and really meeting their individual needs.

An identity-informed approach to trauma is taking into consideration who an individual is and how those factors may influence the way they experience, cope with, and recover from trauma.

An identity-informed approach recognises that an individual's various social identities (like race, gender, class, etc.) can significantly influence their experiences of trauma and their recovery process.

It focuses on understanding how these identities interact with trauma and how they can shape a person's perceptions, responses and access to resources.

Understanding the impact of identity

A person’s identities play a significant role in how they experience, process and heal from trauma. An identity-informed approach focuses on the three key impacts, as shown below:

Intersectional lens | Trauma-informed care acknowledges that individuals hold multiple, intersecting identities, and these identities can create unique vulnerabilities to trauma and influence recovery. |

Cultural context | A person's cultural background significantly shapes their understanding of trauma, their coping mechanisms, and their help-seeking behaviours. |

Social determinants | Factors like socioeconomic status, migration status, and disability can also play a crucial role in how trauma impacts an individual. |

Some of the benefits of using an identity-informed approach include:

Reduced retraumatisation | By understanding the impact of past trauma and creating supportive environments, these approaches can help prevent further harm. |

Recovery | By addressing the unique needs of individuals with diverse identities, trauma-informed care can promote healing and wellbeing. |

Enhanced engagement | When individuals feel safe, respected, and understood, they are more likely to engage in treatment and support services. |

You will now explore two frameworks and engage in a task that can help you to understand and utilise identity-informed approaches better in your classroom and wider school.

Identity-informed schools

Using an identity-informed approach and viewing situations through an identity-informed lens can help you better understand and support all students.

It can also help you avoid making certain assumptions or jumping to conclusions regarding behaviour, attainment and the impacts of trauma.

To understand the importance of an identity-informed approach, we need to understand three key theories – intersectionality, the invisible knapsack and the social GRACES model.

Intersectionality

Kimberle Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to describe a type of analysis which provides a more comprehensive way of understanding how our various identities overlap and interlink so that we can provide better support to people by gaining a better understanding of the challenges they face and the biases we may hold towards them (Crenshaw, 1989).

Intersectionality helps to understand the different ways that a person’s identity can bring them power or oppression in the society they currently live in.

For example, if you are a white student, your race will have unlikely been a barrier to gaining certain opportunities such as a place on a certain apprenticeship programme or on a college course. In fact, in many countries, your race may make it easier for you to be welcomed into certain spaces and take advantage of certain opportunities.

Now let’s consider those parts of your identity which don’t bring you power in your society and can actually act as a barrier or a risk of oppression.

If you are a white female student, it is unlikely that you will have experienced structural racism, but you are likely to have experienced misogyny to some extent, and this may well have been a barrier for you to access certain opportunities. For example, being bullied during your apprenticeship in Construction and facing daily jokes about your inability to complete your work as well as your male peers. In this case, a female student may leave the course because of the oppression she is facing based on this part of her identity.

If you are a Black female student, you may have faced the double oppressions of structural racism, plus misogyny. Intersectionality helps us make meaning of these complex power dynamics, helping us on the first step to undoing them and ensuring equity for our students.

The invisible knapsack

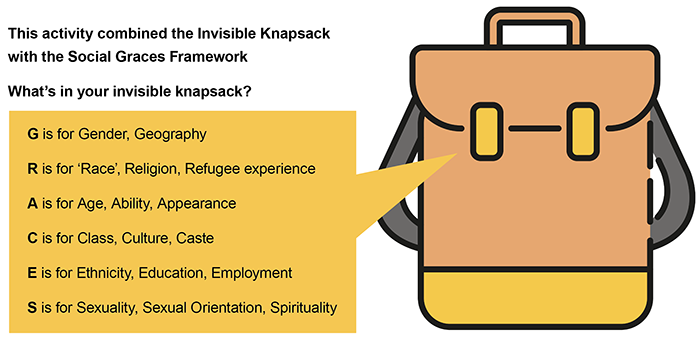

The invisible knapsack is an activity created by Peggy McIntosh which is meant to help you examine your various identities and the privileges and oppression that we carry with us throughout our lives in each society we live in (McIntosh and Privilege, 1989). It builds on the theory of intersectionality and gives people a tool to begin analysing their overlapping identities.

It was intended to help us better understand each other and challenge any biases we may have towards each other and ourselves.

This can be a very useful activity when thinking about how your school treats different members of the community and also to reflect on the needs of groups who may be members of minority groups in your setting.

For example, a student who is religious may require a place to pray during the school day. A student who is not religious will not require this. Factoring in this part of their identity is crucial to ensure their specific needs are met. Equity is achieved through providing different resources to allow students the same outcome rather than providing the same resources to every student.

The Social GRACES Framework

The Social GRACES Framework is an acronym standing for Gender, Geography, Race, Religion, Age, Ability, Appearance, Class, Culture, Education, Employment, Ethnicity, Sexuality, Sexual orientation, and Spirituality. It is another tool to help us understand our intersecting identities.

Created by John Burnham and Alison Roper-Hall, it is a tool used to understand how different aspects of personal identity intersect to create power and privilege differences. It explores how out intersecting identities can also put us at risk of different oppressions depending on the society we are currently in (Burnham and Roper-Hall, 2017).

For example, a student who belongs to the Pashtun ethnic group in Afghanistan will gain certain privileges due to how this group is treated and viewed in Afghanistan. However, if that student is displaced to Pakistan, he will likely face persecution and oppression due to his ethnicity, as Pashtun people are often shunned and targeted by the Pakistani military and government. His identity has not changed but the way it impacts him has.

The Social GRACES Framework is often used by social workers, healthcare professionals and teachers to analyse the unconscious biases we may hold towards certain groups and how that impacts the work we do with individuals belonging to those groups.

The invisible backpack framework when combined with the Social GRACES Framework can create a useful activity for reflecting on the multiple and overlapping identities every person in school has. In the following task, you will explore how these frameworks combine to make a useful tool.

Task 6: The invisible knapsack

Task 6: The invisible knapsack

Look at the GRACES model below and note what each letter stands for.

Use this model above to complete the blank version of the knapsack below with your own personal information.

| G |  | |

| R | ||

| A | ||

| C | ||

| E | ||

| S |

Comment

Hopefully, this activity helped you to gain deeper clarity over your own overlapping identities and gave you time to reflect on just how important these are in shaping your experiences in society. Take this knowledge back into your classroom and consider facilitating an age-appropriate version of the invisible knapsack (e.g., what makes you who you are) to help get to know your students better and use this knowledge to provide appropriate support where needed.

This tool can be adapted to be age appropriate. With younger children you can ask them to decorate their backpack with things that make them who they are. Students should only be encouraged to share what they are comfortable with, and teachers can model this activity for the class to show they types of things students can choose to share.

The invisible knapsack helps you to analyse how our identities can and do impact everyone's life and the way people view and treat others – this goes for your students too.

For some students, they will see people of their race and culture widely represented throughout the curriculum and be able to better identify with the content as it reflects their lived experiences. For others, they may only see their culture represented in a History or Geography lesson very occasionally or in a background character in a novel or play.

Some students will see people of their race regularly linked to crime in the news or on social media and they may notice that their behaviour is challenged or punished more than other students in class who are behaving in the same way.

It is vital that educators and other school staff become better at seeing and understanding these prejudices linked to identity so they can unlearn them, unteach them and examine their own behaviour towards their students which they may not have noticed before.

People's identities shape the way they are treated, the way they exist in their societies and, ultimately, the ways in which they can heal. If schools are not inclusive, both in their treatment of all students and the inclusion of their identities in the curriculum and school life, students may struggle to feel safe, welcome and to heal. It may be uncomfortable to have these conversations and to reflect on your own assumptions and behaviour, but it is vital work if schools are hoping to support all our students effectively.

Bringing identity into the classroom

Healing can take place through learning as well as focused wellbeing support. One way to aid this is through improving self-worth for your students by celebrating parts of their identities in lessons.

Think of a topic you have taught previously. Reflect on how you could bring elements of your students’ identities into their learning.

Consider the following examples for inspiration.

“I’m a Food Technology teacher and I encourage the children to bring in recipes from their cultures. They help to teach the recipes to the class and share information about the origins of the food. The students look so proud to be able to share a part of themselves and show off who they are.”

"I'm a History teacher and I ask each of my students to choose an event that they believe had a significant impact on the country of their ancestors."

"I'm an English teacher and I set homework for my students to find and translate poems from a country they have ancestral links to."

"I'm a Geography teacher and I asked each of my students to bring a case study of a natural resource found in a country they have a family link to."

In this section, you have looked at using an identity-informed approach to help you better understand and support all students. This is an important aspect of trauma-informed care. Another important aspect is psychosocial support that you are going to study next.

Psychosocial support as a route to healing

Psychosocial support (PSS) is a core component of trauma-informed care. Trauma-informed care is a framework that recognises the impact of trauma, and psychosocial support provides the essential emotional, social, and psychological assistance needed for healing and recovery after a traumatic event. The Healing Classrooms Approach prepares educators to provide PSS in their settings.

Psychosocial support (PSS) is a crucial component of trauma-informed care, as it addresses the mental, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of individuals who have experienced trauma.

Psychosocial support can be both preventive and curative.

It is preventive when it decreases the risk of developing mental health problems. It is curative when it helps individuals and communities to overcome and deal with psychosocial problems that may have arisen from the shock and effects of crises.

These two aspects of psychosocial support contribute to the building of resilience in the face of new crises or other challenging life circumstances (Papyrus Project, 2023).

“A lot of psychosocial support may seem like common sense because it is… our relationships can help us to stay well.”

Psychosocial support can be achieved by teachers, social workers, family members and friends – including adults and children. A school football club could be an example of psychosocial support where young people can have fun together, build their self-worth, celebrate wins and build relationships within the team.

The psychosocial support framework

“PSS is a process of facilitating resilience within individuals, families and communities.”

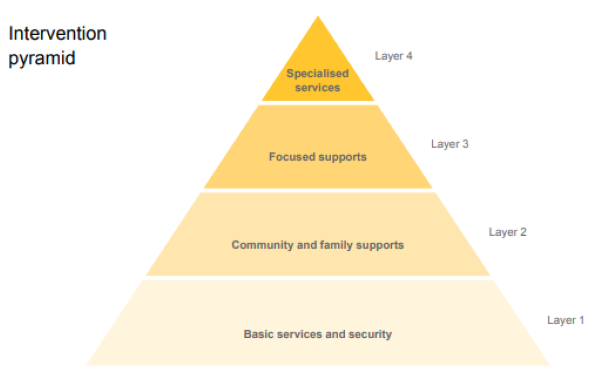

- Not everyone who has experienced traumatic events needs specialised mental health care.

- Good quality psychosocial support can help most people to recover.

- Classrooms which are healing spaces can provide this effectively.

- A lot of what you will already be doing is trauma informed.

Task 7: Intervention pyramid

Task 7: Intervention pyramid

1. Look at the intervention pyramid diagram below.

2. Using the drop-down menus below, try to match the suggested strategies with the correct layer of support on the intervention pyramid.

Comment

The Psychosocial Intervention Pyramid can help educators to see the value in everyday activities to help resettle refugee students. For example, a group activity which allows for relationship building, a school that is safe and nurturing, a teacher who takes the time to build a relationship with a new student. Most students only need these simple things in order to heal along with time to feel stable in their new setting.

Examples of psychosocial support in school

Click on each of the tiles below to learn how former trainees on the Healing Classroom programme have implemented psychosocial support in their schools.

“PSS aims to help individuals recover after a crisis has disrupted their lives and to enhance their ability to return to normality after experiencing adverse events.”

What is healing?

“The internal alarms can turn off, the high levels of energy subside, and the body can re-set itself to a normal state of balance and equilibrium.”

Look at the diagram below which explores the different areas of healing.

Use your mouse to hover over each section in the diagram to reveal examples of what this could look like for a person who has experienced forced displacement.

Task 8: Case study – the Rezai family from Afghanistan

Task 8: Case study – the Rezai family from Afghanistan

A new family has moved to your town from Afghanistan. They fled their country due to ongoing political unrest since the Taliban took over.

Both parents worked as translators for the British Embassy, so have excellent levels of English. Their two children Abdullah and Ayesha, speak some English due to this.

The family are one of very few Afghan families in the local area. The children often feel quite isolated and overwhelmed at school and can become withdrawn. Their parents have explained how they had to leave most of their relatives in Afghanistan and are lacking support and a sense of community.

How can you use the collective healing methods discussed so far to help this family to heal?

Write your notes in the text boxes below.

| Suggested activity | Intended impact |

|---|---|

Comment

This activity highlights the importance of community and collective healing methods for individuals who have been forced to leave their home, culture and community behind.

Unit 2 Summary

In this unit, you familiarised yourself with trauma-informed care and zoomed in on specific areas of this theory namely, an identity-informed approach and psychosocial support.

You explored examples of these approaches being put into use in schools to help support refugee students.

You reflected on your own identity and the importance of an individual’s identity in their experience of trauma, their ability to cope and their pathway to healing.

Finally, you put all of this learning to use in a case study where you were asked to provide appropriate support to a family who had resettled in the UK after being forcibly displaced due to unrest in their home country.

You will now move to Unit 3, where you will explore the first step to the Healing Classrooms Approach: Preparing a Safe Place to Land.

But before you do this, please complete a short multiple-choice quiz to solidify your learning.

Moving on

References

British Red Cross (2022) Psychosocial support [Online]. Available at: https://www.redcross.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/psychosocial-support (Accessed 16 June 2025).

Burnham, J. and Roper-Hall, A. (2017) 'Commentaries on this issue', Context, 151, 47-50.

Crenshaw, K. (1989) 'Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics', u. Chi. Legal f., p.139.

Foundation House (2022) Foundation House Annual Report 2022-2023 [Online]. Available at: https://foundationhouse.org.au/news/foundation-house-annual-report-2022-2023-published/ (Accessed 16 June 2025).

Inter-Agency Network for Education In Emergencies (2023) INEE 2023 Annual Report [Online]. Available at: https://inee.org/resources/inee-2023-annual-report (Accessed 16 June 2025).

McIntosh, P. and Privilege, W. (1989) 'Unpacking the invisible knapsack', Peace and freedom, 49, pp.10-12.

Papyrus Project (2023) What is psychosocial support? [Online]. Available at: https://papyrus-project.org/what-is-psychosocial-support/ (Accessed 16 June 2025).

Victoria State Department (2022) Better Help Initiative [Online]. Available at: https://www.vic.gov.au/ (Accessed 16 June 2025).

Welcome House (2022) Supporting Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Hull and East Riding [Online]. Available at: https://welcomehousehull.org.uk/ (Accessed 16 June 2025).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the real children and families whose stories inspired these case studies and all of the past participants who have shared their examples of good practice which have all helped feed into this course.

Thanks to Mohamad Alrefaai, a former refugee from Syria, for narrating the poem in this unit.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Important: *** against any of the acknowledgements below means that the wording has been dictated by the rights holder/publisher, and cannot be changed.

572953: Shukria Rezaei

572967: Image Provided by International Rescue Committee (IRC) Text adapted from John Burnham's acronym 'social graces'

572934: Adapted from image By Kateryna Fedorova Art/Shutterstock

572932: Wirestock Creators/Shutterstock