Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 10:18 PM

Unit 3 – Preparing a Safe Place to Land

Introduction

You will begin by reading a poem written by a London-based poet, JJ Bola, who has lived experience of being a refugee.

His poem explores themes of racism, anti-refugee hostility, resettlement, assimilation and gives a first-hand account of what it can be like to resettle in a new country after fleeing danger in your own.

In this unit, you will explore challenges refugees may face when they arrive in their new country, strategies for schools to help students and families to cope and explore real accounts of how teachers have adapted their work to provide the support needed for refugee students to resettle.

You will work through a series of case studies to try out the strategies you learn about in this unit and find a range of useful tools that you can download and utilise in your daily work.

You will also start working on an action plan for Preparing a Safe Place to Land, which you will complete by the end of this unit.

In this action plan, you will select the strategies you wish to take away and try out in your classroom or wider school. This action plan can help you to focus on your chosen strategies and reflect on how they have worked. Or ways in which you would like to adapt them, so they are more appropriate to your setting.

In Units 4 and 5, you will work on two more action plans, so you have one per unit.

Unit 3 Objectives

Unit 3 Objectives

- Explain the importance of creating a sense of control and a sense of self-worth for children who have experienced conflict and displacement.

- Explore tried and tested strategies to Prepare a Safe Place to Land for newcomers and existing refugee students.

- Implement key strategies using case studies and consider how they could be successful in your own context.

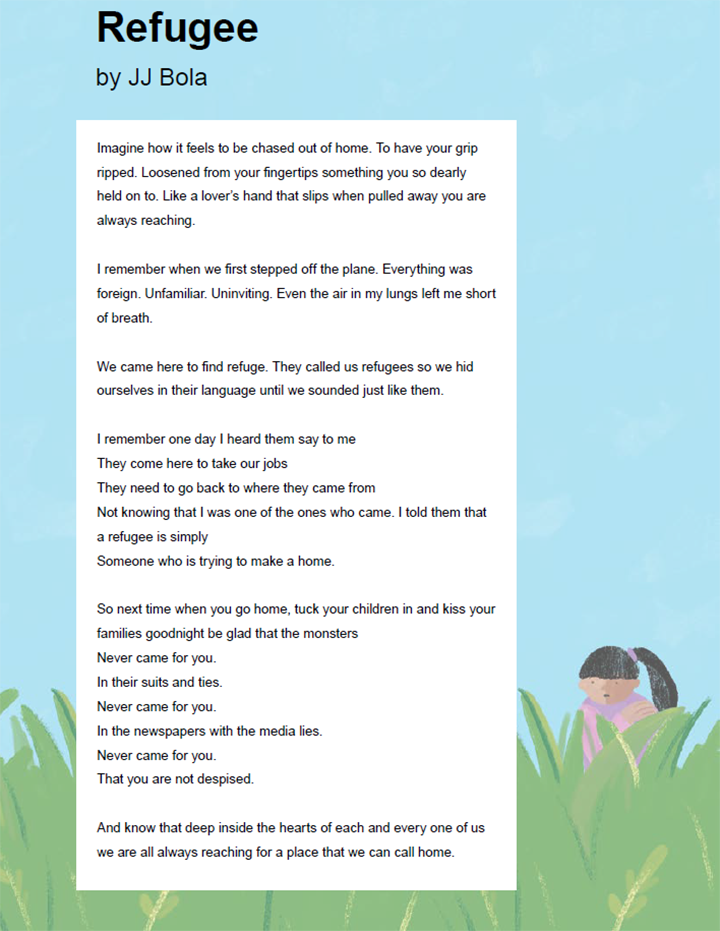

Poem – Refugee by JJ Bola

This poem highlights the importance of schools becoming safe, respectful and responsive communities for new refugee students – a safe place for them to land.

You can listen to the poem if you prefer. Or why not read and listen at the same time?

Transcript

These audio poems are a great resource to use in class.

As you work through this unit, keep in mind the themes in this poem and the importance of making schools places of welcome and sanctuary, especially at times when students and their families may be facing various types of hostility in the wider community.

Preparing a Safe Place to Land

Why do students need a safe place to land? Click on each number to learn more.

| Brains that are stuck in survival mode (constantly monitoring threats) cannot focus and learn. |

| Students who feel safe, welcome and understand what’s expected of them can finally begin to settle and start to learn. |

| School needs to be safe spaces where there are no sudden surprises and everyday follows a clear routine. |

Task 9: Put yourself in their shoes

Task 9: Put yourself in their shoes

JJ Bola helped you to explore some of the challenges that newcomer refugees may face in their communities and wider society.

As a teacher, you may already be aware of the specific challenges refugee students may face in school, especially if they are new to the language and if they have experienced gaps in their education or negative experiences of schooling in the past.

- Imagine you are a child who has had to flee the UK because a sudden war has broken out. Your family are one of the lucky few to be chosen for resettlement through the UNHCR and you find yourself entering this classroom on your first day of school. Imagine you don’t speak the language, and you have never visited this country before.

- List five things that the school, staff and pupils could do to Prepare a Safe Place to Land for you and your family. For example, offering a translator when meeting with you and your parents.

Comment

Now that you have taken the time to consider what it might be like to be a refugee student in a new country, a new school with a new language and culture, take a moment to reflect on the support your school already provides.

Refugees are often seen as numbers rather than individuals and can often feel like they have no control over their lives or futures. Rebuilding feelings of self-worth and control over their daily lives and choices is vital. Most importantly they need to be welcomed calmly into their new community.

You will now review some tried-and-tested strategies to help prepare a safe place to land in your school.

Recommended strategies for Preparing a Safe Place to Land

Establishing routines in school

A classroom routine creates stability in a child’s day. A schedule that is predictable, coupled with a structured environment, lends to a child’s feeling of security and control (University of Kansas, 2000).

There are simple activities that can aid in establishing a routine such as greeting students by name in the morning as they enter school, going over the class schedule and lesson objectives each day, and beginning and ending each day in the same way, such as with a brief class meeting to discuss what students have learned and upcoming topics (Elias, 2003).

Also, offering positive messages at the very end of the day and telling students that you will be happy to see them tomorrow adds another positive element to the routine. For younger grades, this could be in the form of a song that has encouraging words (UNICEF, 2009).

Use your mouse to hover over each tile in the interactive diagram below to reveal examples of recommended strategies to help you establish routines in your classroom and wider school.

You will now explore strategies to establish consistency in school and then explore strategies to utilise positive behaviour management.

Establishing consistency

The following techniques are built on the bedrock of trauma-informed and identity-informed approaches and aim to help students to feel welcome, in control and settled in the classroom.

Firstly, you learn about strategies that establish consistency and then you read about suggestions for positive behaviour management.

1. Orientation in school and in the community

Orientation around the school campus should be given in an understandable way to newcomers to show amenities like toilets and dining halls but also services like the school counsellor, reception and bus stop – using translators, if possible. A basic school map with translations or multilingual signs can be a great help to newcomers.

Students should be paired with another student who is on a similar timetable for the first few weeks until they can navigate the school independently. Students should be directed to support services and facilities like prayer rooms, if appropriate.

2. Buddy and mentoring schemes

Buddy schemes work best when they are properly structured with aims and objectives, are overseen by staff with regular check-ins, and reward students for taking part. Students should be paired up by a staff lead who will oversee the buddy programme.

A clear structure and objectives for the programme should be shared with students, parents, and other staff. Staff should carefully oversee the programme, meeting regularly with students involved in pairs and in groups. A strong focus on social emotional learning competencies can be embedded using the IRC Games Bank and Lesson Plan Bank.

Rewards and certificates should be given to amplify the significance of the programme. Before the programme starts, all mentees should receive foundational training about the services the school provides, how to report safeguarding issues, brief information about the student, and key steps to being an effective mentor. Download our Being a Buddy Pack.

3. Exit cards and designated safe spaces

Provide children with an exit card and explain to them that if they are feeling overwhelmed or panicked, they can show the card to any teacher, and they will be given time in a designated safe space with a member of staff to calm down.

This space should be equipped with mindfulness posters, toys and objects to calm down and drawing facilities. The member of staff should be trained in Psychological First Aid.

If you are interested in this topic, in your own time, you can check out this free course on the FutureLearn platform: Psychological First Aid: Supporting Children and Young People.

4. Embed social and emotional learning (SEL)

Social and Emotional learning (SEL) is proven to help mitigate against the impacts of toxic stress to help children recover. It is also useful for preparing all children to become emotionally intelligent adults who can cope with stress and adversity. The IRC provides a SEL Games Bank and Lesson Plan Bank for use in schools.

The IRC SEL resources focus on conflict resolution, brain building, social skills, perseverance and emotion regulation. In your own time, take time to read through the free resources and use them in assemblies, classroom activities, PE, and break times to teach SEL in a fun, interactive and effective way.

5. Assigned pastoral staff with trauma training

Ensure as many staff as possible have completed online psychological first aid training and trauma-informed practice training. The Healing Classrooms approach and the CPD course you are currently studying on is an example of such training.

Pastoral staff and designated safeguarding leads should be completing regular trauma training and have a strong awareness of refugee experiences to ensure children’s needs are being met. This can be done by reaching out to local refugee support groups or national organisations. To find local groups, search refugee support online in your local area or ask your local council for a list of organisations.

Mindfulness should be used with children across the school alongside social emotional learning games and lessons (IRC, 2019) – use the free SEL Games Bank and Lesson Plan Bank from the IRC.

Pastoral staff should also be seeking to build strong ties with new families, using translators, if necessary, enable families to collaborate with school to support their child’s education and to signpost families to basic services such as healthcare, English language support, and employment opportunities if they are unaware of this support.

6. Consistent routines

Ensure you have clear routines in the classroom for greeting students (try using home languages too), reviewing the visual timetable for each day, checking in with pupils, lining up and entering the room calmly, classroom roles, for example, book monitors, activities at break and lunch to facilitate friendships and calm transition between lessons using buddies.

Positive behaviour management

1. Co-creating classroom rules

Engaging students in understanding and creating rules to govern classroom behaviour can support a sense of control and a positive learning environment.

Establishing clearly defined classroom rules that compliment class routines boosts a sense of stability and calmness in the atmosphere.

By actively involving students in the creation of classroom rules, it will likely increase their adherence to the defined boundaries as they feel a sense of ownership and stronger incentive to cooperate (University of Kansas, 2000). When students feel that they have a voice in the way the classroom is run, they are more likely to take responsibility for self-monitoring classroom behaviour.

Another component is that disciplinary measures should be applied consistently and in a manner which prompts students to think about and learn from their mistakes. For example, a teacher or other staff member can meet with a student involved in disruptive behaviour to discuss what the student felt before and during the incident, why they made specific choices, and alternative actions they could have chosen (Pasi, 2001).

2. Five core rules

Having students choose rules gives a sense of control and ownership over the classroom. By keeping the list focused and limited to five rules, it allows all students to remember the rules.

Teachers should guide this rule-making activity around acceptance, respect, and compassion to help students choose rules that make the classroom a healing, safe space. Allow students to vote on rules to teach democracy, community building, and empathy.

Students can work together to create a poster displaying the rules of their classroom on the door or wall. Examples of rules could include “we show respect when a student is speaking but listening and being quiet”, “we don’t touch other people’s things unless we have asked first”, “we work as a team and offer help if another student is struggling”.

3. The clean slate

Mistakes are forgiven – every lesson offers a fresh start and chance to succeed. Provide a safe space for children to grow and learn.

Refugees may display certain behaviours in response to trauma – and it is vital that teachers move on from these, every lesson, and see the potential for change. Focus on emotion regulation games and lessons as a solution, rather than punishment and a hostile classroom.

4. Clear and consistent consequences

Students who are aware of boundaries are more likely to feel calm and in control of their behaviour. Students lose faith in rules and consequences if they are not applied consistently and fairly.

Dedicate a lesson to deciding fair consequences for students who break the rules. These should be common sense-based, for example, “we are putting the paint away now and stopping this activity because people are throwing paint around and being silly. We will have to spend our time cleaning up now instead of using it to finish our paintings”.

5. High expectations for all

Never assume that refugee students will not succeed or are not intelligent due to education gaps, language barriers and potential trauma. We must set high expectations for all students and identify ways to fill any learning gaps they may currently have.

The EAL Academy (an organisation that supports schools to provide better support to English learners) strongly encourages schools to place refugee children in high ability sets or on high ability tables so they can see good models of learning and use of English.

Placing newcomer refugee students in lower ability sets or tables isn’t necessarily the appropriate place for all students. It can often mean they won’t be academically challenged appropriately for their individual needs, and they could miss out on learning opportunities that other students in their year are getting. Students should be given time to settle in and then placed in the appropriate ability group.

Students in higher ability groups can often provide more support to new students, as can teachers, as the students in these classes are often more independent.

6. Meaningful praise

Using praise for small achievements academically, socially and behaviourally can help guide a student’s behaviour in a positive way rather than using the threat of punishment to push students into line.

Some newcomer refugee students may have had traumatic experiences in school before, such as experiencing the use of corporal punishment, racism and xenophobia from students and staff and other kinds of bulling.

Teachers collaborating with students and showing that they are noticing the work they are doing can help rebuild this trust and show students that they are valued and important members of the school community.

7. Personal goals

Refugee students have been disrupted in monumental ways.

Many have gaps in their education and may not have been given space to think about their future and goals. Teaching children to set achievable goals for themselves serves to increase their self-efficacy which leads to improved task performance and an increase in motivation.

Consider setting goals in a holistic rather than purely academic way, focusing on social skills, feelings, behaviour and participation to encourage the child’s inclusion in your school community.

For example, I will try to take part in one game at lunch time; I will use the breathing exercise if I feel overwhelmed; I will put my hand up to give a suggestion today. Remember that even the smallest steps can be huge for children who have experienced so much.

A staff member should work with the child on these and check in with regular rewards even for little wins to show that the child’s success is noticed and valued.

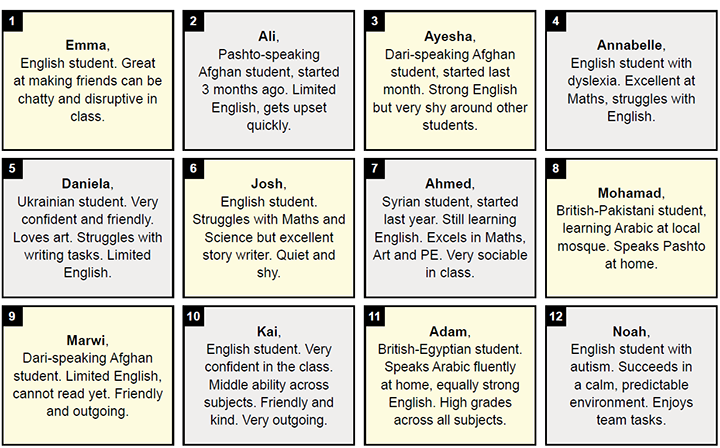

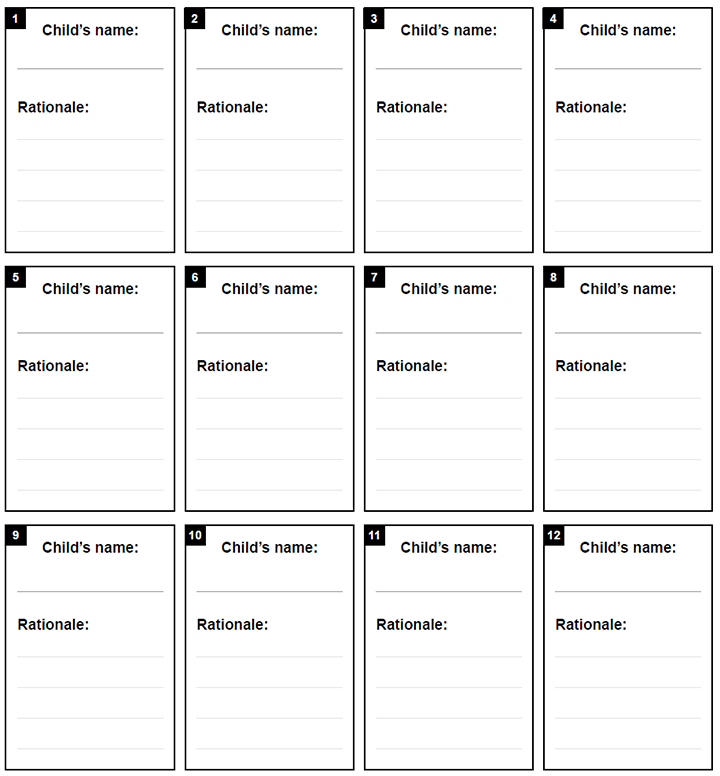

Strategies sheet and seating plan

Please download the Strategies Sheet so you can refer to this list as you complete the remaining tasks in this unit.

Below you will find a seating plan activity to download and use in your own time. This helps you consider if the students in your classroom are seated in the best places to support and challenge each other.

You may wish to use this in a staff meeting and work in small groups to discuss which students should be placed where and the reasons justifying this before asking your colleagues to reflect on their seating plans and how they are utilising students’ strengths, knowledge and skills to support each other and work well together.

You can download a PDF of the Seating Plan.

Task 10: Case study – Abdullah from Sayyan, Yemen

Task 10: Case study – Abdullah from Sayyan, Yemen

Now you have had time to familiarise yourself with the strategies, take a moment to read through the following case study and choose three strategies that you believe would be most appropriate to support this specific student.

Complete the table below justifying why you chose each strategy and how it could help that specific individual.

Abdullah from Sayyan, Yemen

Age: _________________ (Choose an age group that you work with)

Abdullah fled Yemen with his brother and father due to the famine and frequent bombings from Saudi Arabia.

His mother – a university lecturer – was invited to a conference in Europe and overstayed her visit visa to claim asylum and escape the war. Unfortunately, the process is slow, so the rest of the family had to leave before she could apply for reunification for her sons and husband.

They instead had to trust in smugglers to reach the UK. Abdullah is now at your school. He has made a few friends through the football team and speaks English well but is struggling to keep up with the school rules.

Which three strategies would you use to prepare a safe space for Abdullah to land?

| Chosen technique | How I would use it | How it could help |

Comment

Utilising personal goals and meaningful praise could help guide Abdullah's behaviour as well as co-creating five core rules as a class.

Yemen, located on the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, is plagued by war, poverty, malnutrition and cholera, amounting to one of the world’s most severe humanitarian crises. The IRC provides lifesaving assistance and emergency aid. Find out more about IRC’s work in Yemen.

Tools and resources

The IRC has a range of tools and resources to help you Prepare a Safe Place to Land in your classroom and wider school.

Next, you will read through two key resources which can help you to get to know your students better.

You can use these with your whole class and provide your own example so they can learn about you too or you can use these in small groups or one-to-one, depending on your role.

You can share both completed activities with other relevant staff to help them to build a relationship with newcomer refugee students.

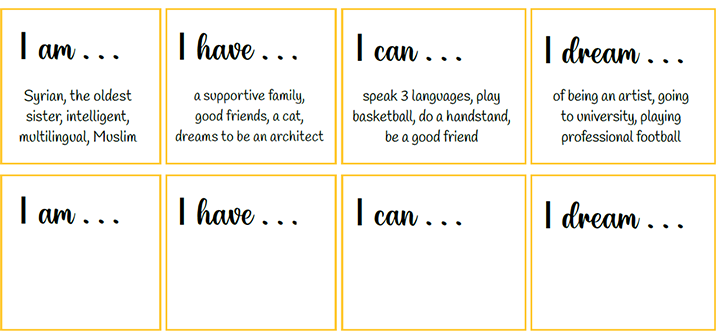

Resource 1: I am, I have, I can, I dream

You can download a PDF of I am, I have, I can, I dream.

A past trainee on the Healing Classrooms programme completed the I am, I have, I can, I dream activity with a newcomer refugee student and shared this with the headteacher.

The head then used the information given (such as a love of basketball) to strike up a conversation in the playground with the new student, helping them to start to build a relationship with them.

The head teacher voiced that “it was a wonderful way to gain insight into who the students are and what makes them tick”.

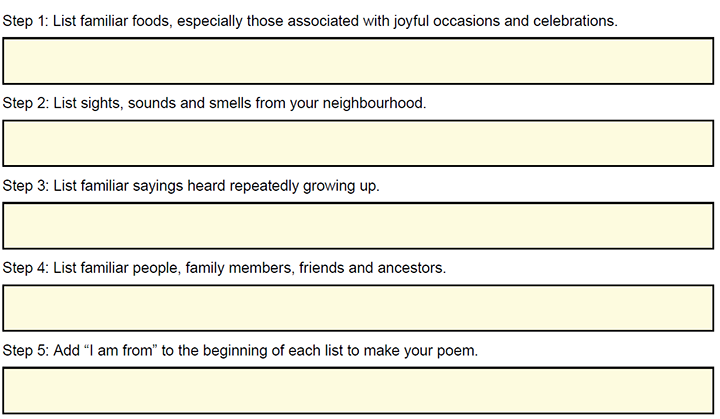

Resource 2: I Am From Poem

The I Am From Poem is a fantastic activity for all students to reflect on who they are and where they come from.

You can download a PDF of the I Am From Poem.

Read the completed I Am From Poem by our Senior Education Officer:

I am from Yorkshire puddings and roast beef,

I am from chip butties dipped in gravy,

I am from little slices of birthday cake with the white icing and jam inside,

I am from back alleys full of kids playing hopscotch,

I am from the smell of curry wafting through the rows of terraced houses,

I am from shrieks and laughing and cars beeping and “quick, car’s coming”,

I am from “going t’shop”, “y’alright chick”, “tarrar see you later”,

I am from Mancunian miners, cotton mill workers and grafters.

You can write your own poem below.

A past trainee on the Healing Classrooms programme said the following.

“I love, love, love the I Am From Poem. We get so hung up on what these students are missing or on how traumatised they might be from bad experiences in their past that we forget to celebrate the good times and the happy memories.

I have used this with two of my classes now as an introductory activity in the first week of term and it is an excellent way for the students to share who they are and for me to get to know them quickly and meaningfully”.

Next you will read through a selection of resources made by IRC and others to help you easily put the strategies you have read about into use in your daily work.

Tools to Prepare a Safe Place to Land

Meet-up with caregivers

In the initial meet-up with caregivers, to ensure you are asking the right questions to prepare the family and the new teacher, use this tool.

It is a collection of key questions with tips and guidance to support families as they join your school. This tool can be used retrospectively with a student who has been at your school for a while, but you lack key information on.

Buddy programme resources

Use our ready-made resources to set up a sustainable and well-organised buddy programme in your school. This pack includes application forms, training slides and a mini-handbook for buddies to ensure the project is meaningful to those involved.

Staff–student mentoring programme

Similar to a student–student buddy programme, a staff–student mentoring programme can provide that one person to confide it and know you are not alone in school.

| Year 7 Vulnerable New Starters mentoring project |

| Potential School Refusers mentoring project |

| Aspirations mentoring project |

| Refugee Newcomer mentoring project |

Staff mentoring schemes work best when they are:

Click on each number to reveal more.

Use the IRC’s Emotion Tracker to start a conversation with students about their day, check for any moments to celebrate and any concerns to support them with.

Try out the IRC’s Weekly Reflection Sheet to structure your meetings. Staff can share appropriate examples from their week, so the conversation is not one-sided (for example, “when I’m tired, I find it difficult too, because I don’t have much energy to concentrate on what I’m supposed to be doing”).

Other tools that can be useful to have to hand for these meetings include the IRC’s Zones of Regulation Worksheets, Feelings Volcano Sheets, Feelings Thermometer Sheets and Check-in Cards. Download and print any of these resources for free.

Positive behaviour management

Below is a behaviour management planner to help you consider which approaches may work best for the student you are supporting:

Clean slate approach

|

Staff mentor

|

Student buddy

|

Goal setting and meaningful praise

|

Five key rules and consistent consequences

| |

Use this template below to consider what might work to support your students.

| |

You can download a PDF of the Positive Behaviour Management Planner.

"An understanding of adverse childhood experiences and adverse childhood environments needs to dictate how we manage behaviour"

Watch this short video to see how less typical behaviour management strategies may have a better outcome for your students.

Task 11: Case study – Miguel from Sonsonate, El Salvador

Task 11: Case study – Miguel from Sonsonate, El Salvador

Using different strategies than you used in the first case study, choose three strategies or tools which you believe would support this specific student.

Miguel from Sonsonate, El Salvador

Age: _________________ (Choose an age group that you work with)

Miguel fled El Salvador after being recruited into a local gang. Sonsonate is currently the murder capital of El Salvador. His parents put him on a plane to England as soon as they could, but they couldn’t afford to bring any other family members.

Miguel is now an unaccompanied asylum-seeking child living in foster care. He can speak some English and has made friends quickly at school but is getting into fights with older students regularly.

Rumours have spread about the gang he was in, and it is causing trouble for him and preventing him from moving on. He had stopped attending school back home and was working full time.

He tells you he finds it strange being treated like a child when he was treated like an adult back home.

Which tools or strategies would you use to help prepare a safe space for Miguel to land?

| Tool or strategy | How I would use it | How it could help |

Comment

A student like Miguel could benefit from being given responsibilities in school, a staff mentor who can work with him to create meaningful goals and to learn more about why the rules are in place and how they benefit the school community.

Levels of violence in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala are akin to those in the deadliest war zones around the world. The International Rescue Committee provides emergency cash relief and lifesaving information services to people in El Salvador who have been uprooted by growing violence. Around 300,000 Salvadorans a year are internally displaced. Read more about IRC’s work in this region.

Action plan – Unit 3

In this unit you have explored the challenges newcomer refugees may face when they arrive in their new country, alongside key themes in our introductory poem.

You have looked through the eyes of a child placed in an unfamiliar setting and tried to imagine the support you would need if you were in their shoes.

You have read through recommended strategies for Preparing a Safe Place to Land to support students as they try to resettle in the UK so they can be shielded from some of the hostility that JJ Bola highlights in his poem, and you have tried out some of these strategies to help the students in two case studies.

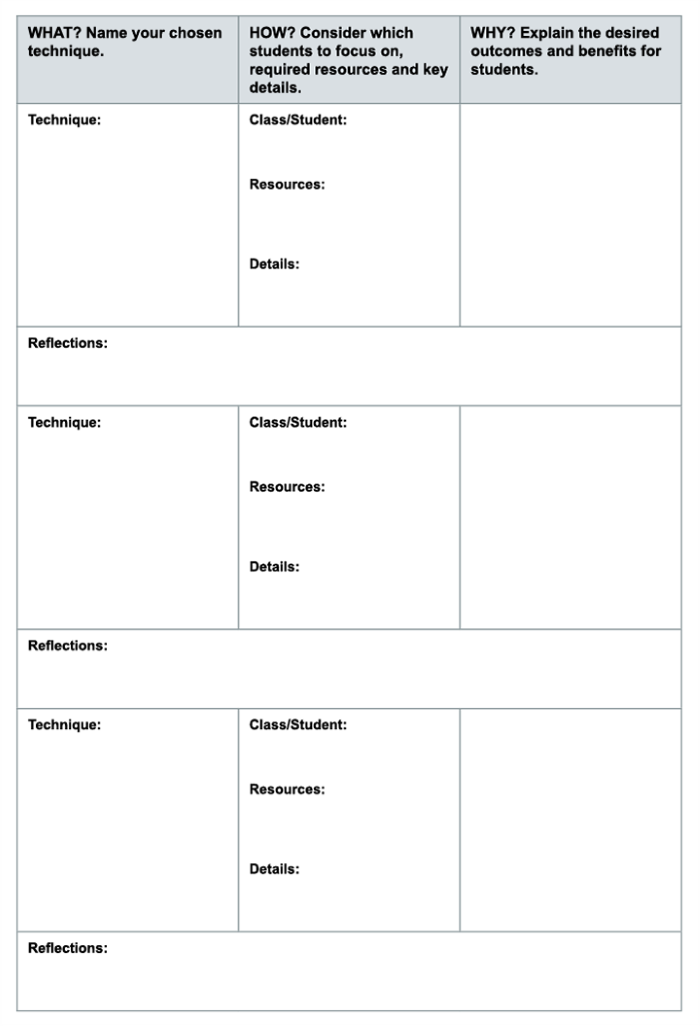

Task 12: Action plan

Task 12: Action plan

Before finishing this unit, complete this action plan to decide which three strategies you will take away from this session to try in your own classroom or wider school.

This is not to say you should limit yourself to just using three strategies forever, but it is a starting point to make meaningful and realistic adaptions to your daily work.

The Healing Classrooms Approach works best when all of the strategies are eventually put into place.

You can download a writable PDF of the Unit 3 Action plan.

Comment

Action plans can help you solidify your knowledge after completing each unit and take away key strategies to try in your own setting. Print and share these action plans with your colleagues and suggest activities you can all try and then feedback after a few weeks to see the impact across classrooms.

Unit 3 Summary

In this unit, you explored the challenges refugees may face when they arrive in their new country, strategies for schools to help students and families to cope and explored real accounts of how teachers have adapted their work to provide the support needed for refugee students to resettle.

You worked through a series of case studies to try out the strategies that you learned about in this unit and found a range of useful tools that you can download and utilise in your daily work.

Finally, you have completed your action plan for Preparing a Safe Place to Land. In this action plan, you have selected the strategies you wish to take away and try out in your classroom or wider school. This action plan can help you to focus on your chosen strategies and reflect on how they have worked. Or ways in which you would like to adapt the strategies, so they are more appropriate to your setting.

You will now move to Unit 4, where you will explore the second step to the Healing Classrooms Approach: Building a community for learning.

But before you do this, please complete a short multiple-choice quiz to solidify your learning.

Moving on

References

Elias, M. J. (2003) 'Academic and Social-Emotional Learning', International Academy of Education, France. Available at: http://www.iaoed.org/downloads/prac11e.pdf (Accessed 24 June 2025).

IRC (2019) This teacher uses mindfulness to help children recover from war. Available at: https://www.rescue.org/article/teacher-uses-mindfulness-help-children-recover-war (Accessed 24 June 2025).

Jarvis, P. (2019 'Why ACEs are key to behaviour management', TES Magazine. Available at: https://www.tes.com/magazine/archive/why-aces-are-key-behaviour-management (Accessed 24 June 2025).

Pasi, R. J. (2001) 'Higher Expectations: Promoting Social Emotional Learning and Academic Achievement in Your School', The Series on Social Emotional Learning. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

UNICEF (2009) The Psychosocial Care and Protection of Children in Emergencies: Teacher Training Manual. Available at: https://inee.org/sites/default/files/resources/Unicef_Psychosocial_Care_Protection_Children_Emergencies.pdf (Accessed 24 June 2025).

University of Kansas (2000) 'Preventative Approaches', Department of Special Education, Special Connections. Available at: https://specialconnections.ku.edu/behavior_plans/classroom_and_group_support/teacher_tools/preventative_approaches (Accessed 24 June 2025).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the real children and families whose stories inspired these case studies and all of the past participants who have shared their examples of good practice which have all helped feed into this course.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Important: *** against any of the acknowledgements below means that the wording has been dictated by the rights holder/publisher, and cannot be changed.

573038: JJ Bola

573039: Tom Saater/IRC

573042: strichfiguren.de/stock adobe

573043: stick-figures.com/Shutterstock

573046: Adapted from original image by Freepik on Flaticon

573048: Dashqin Huseynaliyev/Alamy

573049: mohsin majeed/Getty

573051: by ginkaewicons/stock adobe

573052: Freepik

573053: Redrawn by IRC from Line Art/Getty premium

573054: Adapted from COOL STUFF/Shutterstock

573055: Adapted from Abonti Roy/iStock / Getty Images Plus

573057: Adapted from Ulkar Gurbanova/shutterstock

572934: Adapted from Kateryna Fedorova Art/Shutterstock

572932: Wirestock Creators/Shutterstock