Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 7:19 PM

Unit 5 – Fostering academic success

Introduction

As with all the previous units, you will begin by reading a poem written by Afghan poet and former refugee, Shukria Rezaei.

In this unit, you will explore the challenges students can face with their learning when confronted with a new language, new styles of teaching and learning and new topics which may be completely alien to them at first.

You will uncover recommended strategies to enable new students to flourish academically. In Unit 5, you will explore education through the lens of culturally responsive pedagogy. You will work through a series of case studies to try out the strategies you learn about in this unit and find a range of useful tools that you can download and utilise in your daily work.

At the end of this unit, you will complete your third action plan for Fostering Academic Success. In this plan, you will choose the strategies you wish to take away and try out in your classroom or wider school. This action plan can help you to focus on your chosen strategies and reflect on how they have worked or ways in which you would like to adapt them, so they are most appropriate to your setting.

Unit 5 Objectives

Unit 5 Objectives

- Explain the importance of adapting current teaching and learning methods to ensure children can reach their academic potential.

- Identify ways to use Healing Classrooms strategies to achieve this.

- Formulate strategies to Foster Academic Success for displaced students in your own context.

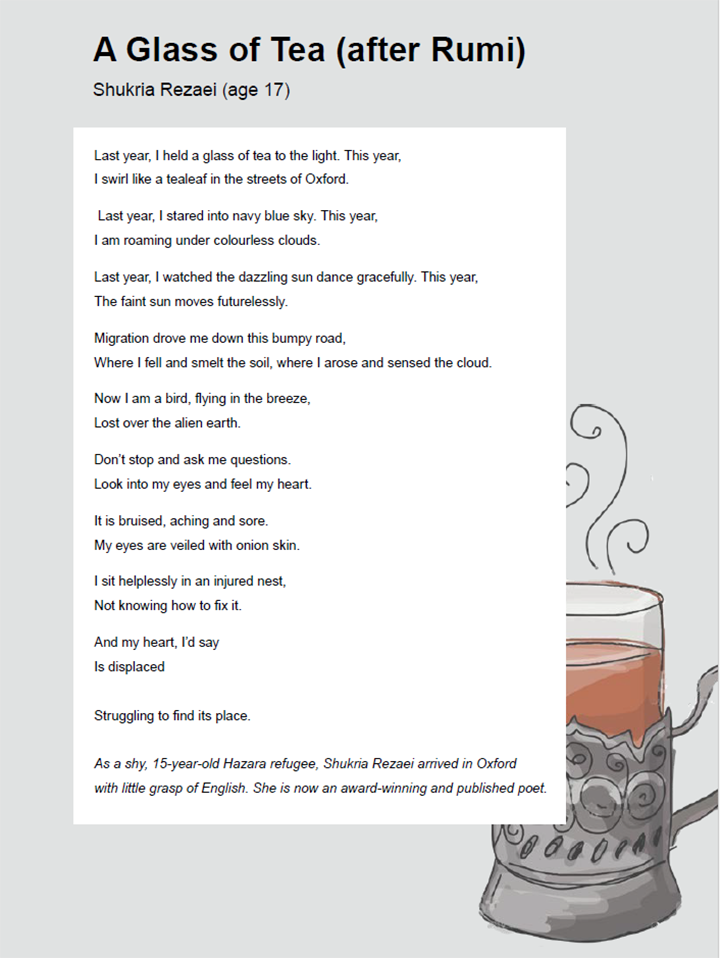

Poem – A Glass of Tea (After Rumi) By Shukria Rezaei

This poem, which Shukria Rezaei wrote as a newly arrived 15-year-old Afghan refugee being resettled from Pakistan to Oxford, covers the quiet feelings of distance that cultural bereavement can leave a child with; the stark differences between home and here; and the feeling of being slightly out of place when you first arrive in a new country.

Shukria's poem gives a powerful first-hand account of what resettlement can feel like for a child or young person and her story of going from English language learner to published poet in a matter of years, shows what young refugee students can achieve when given the right support in school.

You can listen to the poem if you prefer. Or why not read and listen at the same time?

Transcript

As you work through this unit, keep in mind the themes of loss, in its many forms, that are explored in this poem – a loss of self, a loss of home, and of feeling completely out of place and lost in a new country.

But it is also important to keep in mind the vast potential all students have and the importance of teachers and other staff supporting students to learn, to grow and to find who they want to be in the new life they are building in the UK.

In this unit, we will explore strategies and tools that provide you with help to support students in your school.

Fostering academic success

This step focuses on creating intellectually stimulating environments for all students by using culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP).

Why do students benefit from an environment that fosters academic success? Click on each number to learn more.

| Students who are refugees have likely experienced gaps in their education, and schooling using very different methods to the UK. |

| Creating a stimulating environment requires teachers to assess not only the knowledge but the skills children enter the classroom with. |

| Students should be able to relate to and interact with the content rather than just memorise and repeat it. |

| Learning should be a two-way street with teachers and students gaining new knowledge from each other. |

Task 17: Put yourself in their shoes

Task 17: Put yourself in their shoes

- Imagine you are sitting in a classroom, looking at the whiteboard and a worksheet and you can’t understand a word that is written on either.

- List five things the teacher could do to help you access the lesson (for example, add a list of keywords with images next to them, book me in for one-to-one time to learn the basics of the new language).

Comment

Now you have taken the time to consider what it might be like to be a refugee student in an unfamiliar classroom with a new language and teaching and learning style, take a moment to reflect on the support your school already provides.

Many children who’ve experienced displacement have had gaps in their education or received education in informal schools in refugee camps. Educators must acknowledge that lost learning or language barriers are not an indication of academic potential.

Refugee children should be held to high academic expectations and given the support they need to flourish at school. Schools should map out skills, talents and interests of new students to help include them in lessons.

As we saw with the case of Shukria who arrived in the UK with little knowledge of English, students who are given the right support can flourish even in a short amount of time. You will now read a list of recommended strategies to provide such support to students in your school.

Strategies for fostering academic success

All of the following recommended strategies fit into a theory called culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP). You will read more about this theory later in this unit.

Appreciating different cultural and religious norms and knowledge

Students may exhibit behaviours that seem unusual in Britain or hold beliefs about certain subjects that are influenced by their culture or religion. It is important that teachers understand this and appreciate that the types of knowledge which are important in British culture are not universal. Understanding key components of students’ religions can also help teachers prepare for topics which may be new or challenging for them and to avoid causing offence accidentally. For example, it is never appropriate in Islam to depict God or any of the Prophets in pictures or drawings. Whereas, in Christianity, it is common to see pictures, paintings, stained glass windows and statues depicting God and the Prophets.

Honest, open conversations

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) requires staff and students to have honest, open, and sometimes difficult conversations about society and their place in the world. Discussion of culture, religion, poverty and other factors that we see in society are vital to the learning process and helps teachers to understand their students better – putting them in a position to teach them more effectively in the future. Not all students are treated equally in society, and it is important that schools acknowledge this and try to unteach the prejudices leading to these kinds of inequality.

Creative, visual, hands-on and spoken activities

Using debates, discussions, effective questioning and hands-on projects can help students with limited English. These methods can help them access the learning and develop key skills. Giving new students space to speak English is vital even if they only know a few words. Wherever possible use graphs, charts and diagrams to display information so students who don’t have a strong grasp of English can still understand how content fits together (Bell Foundation, 2022). The EAL Academy advises to “focus on visual delivery of vocabulary” (Morrison, 2014).

Utilising all known languages

UNESCO’s research found that “early instruction in the home language can support children’s development of a positive self-image as well as their academic learning, preparing them to acquire foreign languages in the later years of schooling” as children learn a second language more efficiently when they have established a solid foundation in their native language (Dryden-Peterson, 2018).

Students may go back and forth between their languages to write or process, but that just means they are using all the languages at their disposal to learn English. If students are taught to think about the connections between their first and new language, their skills can develop exponentially. Encouraging students to translate songs, poems and short texts using Google Translate can help them to find these connections. When dealing with more complex pieces of work, you can allow students to answer in their native language first before translating it. This increases the chance that the student will better understand the topic.

Building on prior knowledge

If you have children from a range of cultures, countries and religions in your class, use existing knowledge as a starting point for learning. Ask students to present certain topics to show an appreciation of their lived experiences. When teaching abstract topics, look for links to the students’ contexts – be it local or in their home countries. For example, when teaching about gentrification in Geography, show examples in the local community or link it to development in countries where your students may have ancestral roots. When teaching about poetry, find diverse poets who tell stories we don’t often hear in Britain.

Have high expectations of newcomers. Students with refugee status may have experienced an interrupted education but lack of opportunity is not equivalent to lack of ability. Provide them with every opportunity to grow and develop as learners and community members. Refugees may require more guidance and support to reach aspirations.

Connect with families to check the educational history of your new students. You can use our induction guide to help collect this information. Find out which language they speak and if they are literate. Find out if they have any skills or interests that could help you teach them or build a rapport faster. Activities that enable learners to activate their prior knowledge of the topic of the lesson facilitate greater understanding and engagement.

Example strategies include taking advantage of the learner’s first language and finding out what the learner knows through questioning.

Pre-learning activities

A further technique to allow students to engage fully in lessons is to provide them with resources that outline what will be taught throughout the scheme of work along with key words. This pre-learning will allow students to become more engaged in the lesson. This is particularly useful for refugee students who may have covered the topics in their previous schools, but due to insufficient English, they cannot grasp what they are supposed to be learning and cannot participate.

Group problem solving tasks

Students can build a range of skills such as critical thinking, evaluation and cultural competence by being assigned tasks relating to real-world issues. For example, each group is given a global issue (for example, education, health, poverty) and asked to work together to present solutions. This could be used in PSHE lessons or embedded into humanities and English lessons to help students understand the intricacies of topics and develop viewpoints about them. Big questions work well in primary schools (for example, how can we make the world a happier place?).

Group projects offer students challenge, support and space to develop social skills. They can learn about cultural norms by watching how other students behave and interact. Teachers can facilitate a range of activities such as debates, role plays, project planning and creative projects where students build a product. Many of these learning strategies will help with language acquisition for newcomers and to build friendships.

Diverse case studies, resources and topics

Students will find it easier to engage with the learning if they feel connected to the content in some way. Take time to examine the books, case studies, examples, and images used in your schemes of work. Do they reflect a range of cultures, voices, and experiences or are they all depicting a similar culture, nationality and way of life? Making adaptions to schemes of work even as simple as using pictures of people and places outside of Britain can help students to feel appreciated in the classroom and more interested and willing to engage with the learning.

There are numerous books about refugees for all age groups, including Benjamin Zephaniah’s ‘Refugee Boy’ and Onjali Q. Rauf’s ‘The Boy at the Back of the Class’, and Khaled Hosseini’s ‘The Kite Runner’.

Place English language learners in higher ability sets

English language fluency is not an indicator of academic abilities. Students should not be placed in low sets where they may be exposed to bad behaviour and content that is too easy. Research shows that EAL students placed in higher ability sets pick up the language much faster as they see good practice and a wider range of vocabulary used. They are also able to access the learning due to better behaviour and the teacher having more time to support them, as students are able to work independently. Other students can also offer better support as they have a strong understanding of the content and expectations of tasks.

You can download a PDF of the Unit 5 Strategies Sheet.

Culturally responsive pedagogy

You will now explore a theory which all of this unit’s recommended strategies fit into – culturally responsive pedagogy.

CRP helps all students to learn better by using a vast range of teaching and learning techniques, making the content relevant to the lived experiences of students, and developing growth mindsets in students so they persevere even when the learning is challenging.

CRP helps develop an academic mindset to prepare students for further and higher education where they are required to mull over information until it makes sense.

Where CRP has been used effectively, children experiencing extreme adversity have gained higher grades, have improved school attendance, and have better mental health outcomes overall (Hammond, 2014).

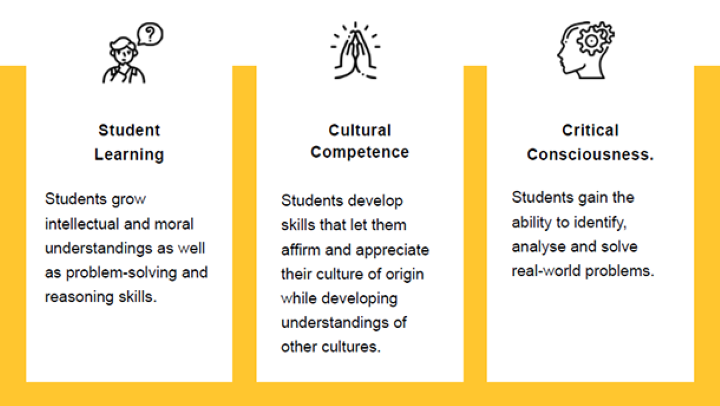

CRP can be broken down into three key components, as shown in the diagram below.

CRP teaches students about the process of learning itself, helping them to appreciate challenge and struggle, rather than always getting to the correct answer straight away. It explores a learning pit, where students may get stuck trying to figure out a task or a concept and it celebrates that moment of confusion and struggle before a student reaches an understanding of the content.

This struggle is what helps students to get into an academic mindset and build the skills required for further and higher education and life after school.

Why is culturally responsive pedagogy vital for refugee students?

Click on each number to learn more.

Strategies to introduce culturally responsive pedagogy into your classroom

Strategies to introduce CRP into your classroom could include the following.

CRP is focused on getting students into an academic mindset where they are confident challenging content, struggling through parts of their learning and sharing their own perspectives and understandings.

Task 18: Culturally responsive classroom

Task 18: Culturally responsive classroom

1. Watch this video to take a look at one example of a culturally responsive classroom.

You can reflect on these questions now or you can take these away and use them to start a short discussion with your colleagues.

- How is the classroom set up to facilitate varied ways of communication?

- How do teachers collaborate to support their students’ learning?

- How are different languages utilised to support learning?

- How would you describe this learning environment in a few words?

2. Watch this video to explore what CRP looks like more generally and across a school.

Comment

As these videos highlight, there is no one way a culturally responsive classroom will look but there are key commonalities in the way educators view their students through a strengths-based lens, utilising their cultures and identities as a starting point for learning.

Task 19: Case study

Task 19: Case study

Now you have had time to familiarise yourself with the strategies and with the basics of CRP, take a moment to read through the following case study and choose three strategies that you believe would be most appropriate to support this specific student. Complete the table below justifying which you chose each strategy and how it could help that specific individual.

Amira from Baghdad, Iraq

Age: _________________ (Choose an age group that you work with)

Amira came to the UK as a refugee several years ago. She often gets in trouble for challenging her teachers, especially in subjects like history. Coming from Iraq and with many relatives still there, she has a different understanding of the role Britain plays in global affairs to the other students in her lessons who are mostly British. Her teachers get frustrated with her and send her out and Amira often complains to her head of year that she’s not doing anything wrong and that she’s not telling any lies. She says she wants to drop history despite it being her favourite subject.

How can this school use CRP to support Amira?

| Chosen technique | How I would use it | How it could help |

Comment

As the case study highlights, refugee students have so much knowledge into bring the classroom and this should be celebrated and built upon rather than pushed aside or minimised.

By giving space for learners to share, challenge and debate the content, everybody learns something new, including the teacher.

Adapting the curriculum to foster academic success

You are now moving on to a section where the topic focuses on adapting the curriculum to meet the needs of your students and how that can be done in many different ways.

Read the example below:

Hadiyah was a Syrian student who loved to read. English was her favourite subject, and she was always asking her teacher how to improve.

Her teacher explained that she was losing marks because she was not showing an understanding of context in her essays. She gave her model answers, and they talked through them together.

After a while, the teacher realised that all of the poems were written by English men about World War I and World War II – events that have a very different meaning in Syrian society than they do in British society. While Syria was hugely impacted by both of these wars (being colonised and used as a place for British army bases), these wars are not a part of the national identity, as many Brits view them as here. Thus, despite the help, Hadiyah is still not grasping this idea of context.

Hadiyah’s teacher wonders how she can tap into a similar link that many Brits have with these wars in a Syrian context. She researches poems written by Syrian poets in English about the recent civil war. After asking Hadiyah if this poem would be useful to her, she gives it to Hadiyah to read as homework and asks her to answer an essay question about it.

While reading the poem, Hadiyah understands the reasons the poet feels so upset and frustrated. She understands why the poet is choosing certain words and metaphors because it links to her prior knowledge and experiences as a Syrian person. Hadiyah finally makes the link between context and writes an excellent essay.

Keep this example in mind as you return to your classroom and consider adaptions that could be made to future topics to ensure all students have various access points to the topic.

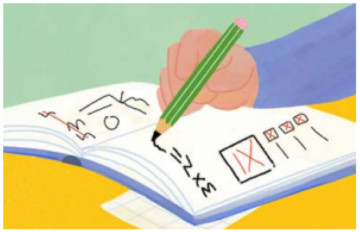

Task 20: Adapting the curriculum

Task 20: Adapting the curriculum

1. Read the following scenario:

You teach the same topic on mountains every year with a case study from North Wales. However, this year you have a new student, Hassan, from Afghanistan.

You’re aware that everything you have taught since he arrived has been about Britain and you want to make him feel more involved and tap into his prior knowledge.

Hassan is from a mountainous village in Afghanistan near the Wakhan Ridge. He speaks English almost fluently and is quite a confident student.

The IRC has a range of tools and resources to help you foster academic success in your classroom and wider school. Below are a series of relevant tools and resources available to download for free from our website.

IRC’s Personal Dictionary for Students

IRC’s Primary School Language Survey

IRC’s Secondary School and Higher Language Survey

IRC’s Strategy Tipsheet for Classroom Management

Gamification

In the recommended strategies list, you read about using games in class to build skills, friendships and to support learning.

There are many simple games which can be used as a fun and collaborative way to learn and help relationships develop between students. Consider how you could adapt games to learn other parts of the English language or use images to make it bilingual so children can learn each other’s language.

Gamification is more than simply adding games to your lesson. It includes taking key concepts from games such as points, scoreboards, levels, challenges and more and weaving these through lessons to encourage children to see learning as a fun, exciting process.

Translanguaging

Refugee students are often seen through a deficit-based approach (for example, he has missed three years of school, she doesn’t know a word of English, he’s never been to school ever).

However, culturally responsive pedagogy views all students through an assets-based approach (she has already mastered two languages, he has developed several skills from his experiences outside of school).

Translanguaging is an integral part of culturally responsive pedagogy which uses all of the known languages of a student to enable them to learn. It can be a lifesaver for children who are learning English, as they can utilise their known languages to access the learning.

To use translanguaging effectively, teachers must use lots of visual and diagrams to get the content of the lesson across but then allow students to take notes, do working out and express their ideas in their known languages before then going on to translate it into English.

This enables children to keep up with the pace of the lesson, to engage better with more complex content and to not miss out on learning due to their lack of English. Always provide EAL students with a spare notebook to complete work in their known languages and actively encourage them to use their known languages to learn.

Click on each number below to reveal four suggested methods for using translanguaging in the classroom.

A former participant of the Healing Classrooms programme said:

“I’m head of Year 10 and when I heard about translanguaging, I thought – amazing, that’s just what we need! I went back to my classroom and spoke to my Year-10 boys, who are still learning English, and I told them, you can write your notes in your own language for revision. You should have seen how excited they were showing off how they could write in Arabic and showing the other students which letters were which. They just looked so proud, and it was really emotional for me to watch.”

You have now covered the 3-step Healing Classrooms Approach:

Preparing a Safe Place to Land.

Building a Community for Learning.

Fostering Academic Success.

Before completing this unit, in the next section you will work on your action plan.

Action Plan – Unit 5

In this unit you have explored the feelings of loss a child or young person will likely feel as they try to settle into their new life in the UK, as you saw from the first-hand account in Shukria’s poem.

You have imagined you were a newcomer refugee student and explored what support you would need in the classroom in order to learn.

You have read through the recommended strategies for Fostering Academic Success and tried out these strategies in a case study activity.

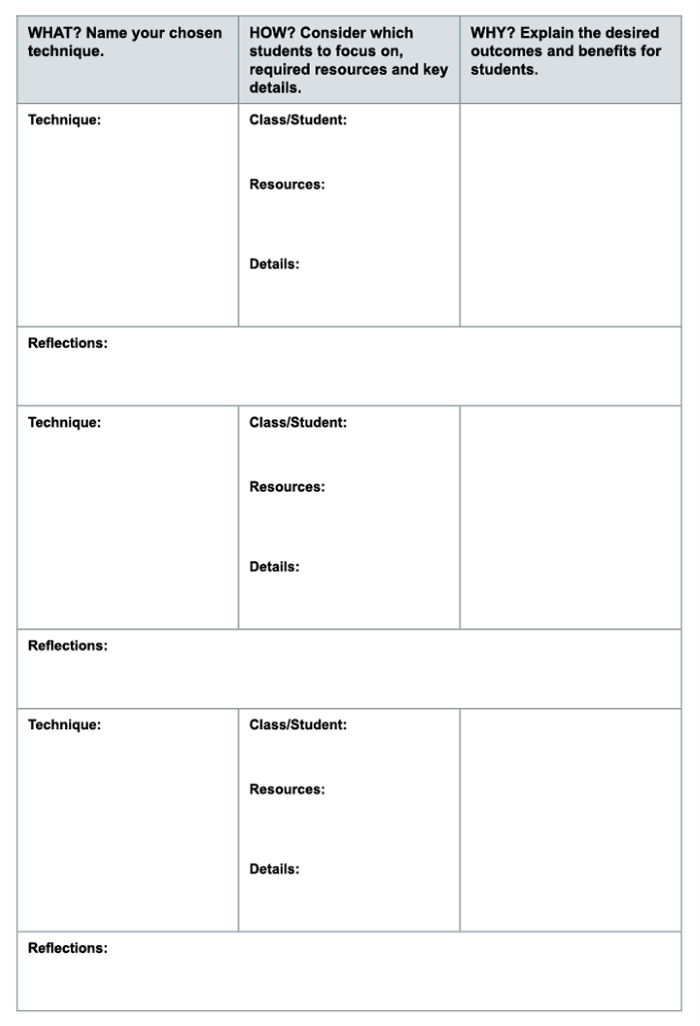

Task 21: Action plan

Task 21: Action plan

Before finishing this unit, complete this action plan to decide which strategies you will take away from this session to try in your own classroom or wider school.

This is not to say you should limit yourself to just using three strategies forever, but it is a starting point to make meaningful and realistic adaptions to your daily work.

The Healing Classrooms Approach works best when all of the strategies are eventually put into place.

You can download a writable PDF of the Unit 5 Action plan.

Comment

Action plans can help you solidify your knowledge after completing each unit and take away key strategies to try in your own setting.

Print and share these action plans with your colleagues and suggest activities you can all try and then feedback after a few weeks to see the impact across classrooms.

Unit 5 Summary

In this unit, you explored the challenges students can face with their learning when confronted with a new language, new styles of teaching and learning and new topics which may be completely alien to them at first.

You uncovered recommended strategies to enable new students to flourish academically, explored education through the lens of culturally responsive pedagogy, and worked through a series of case studies to try out the strategies you learned about in this unit and found a range of useful tools that you can download and utilise in your daily work.

You also completed your action plan for Fostering Academic Success and chose the strategies you wish to take away and try out in your classroom or wider school. This action plan can help you to focus on your chosen strategies and reflect on how they have worked or ways in which you would like to adapt them, so they are most appropriate to your setting.

This is just the beginning, so what now?

Congratulations! You have now completed the Healing Classrooms Course.

You have explored an introduction to trauma, different routes to healing including trauma-informed and identity-informed approaches, and the 3-step Healing Classroom Approach – the IRC’s trauma-informed approach to educating children exposed to crisis, displacement and potential trauma.

You have covered key theories such as trauma-informed care, identity-informed care, psychosocial support, cultural competence and humility and culturally responsive pedagogy – all of which are combined in the recommended strategies you have read in this course.

Now, consider the following ways that you can utilise what you have learnt:

Sign up your school for a whole staff training with a Healing Classrooms facilitator – for the 3-part Basics course or for the 5-part accredited CPD course. Alternatively, book a free Healing Classrooms Conference by emailing healingclassrooms.uk@rescue.org.

Sign up to become a Healing Classrooms Champion (our train-the-trainer programme) running since 2024.

Come along to our Monthly Monday Munch Club (a community of practice where we hear IRC speakers and others discuss refugee education). To sign up simply, drop us an email to healingclassrooms.uk@rescue.org.

Share the information you learnt and the resources with your colleagues, as well as recommending that they also study this online course.

Read through the IRC resources to see what you can use to benefit your students.

Arrange meetings/discussions with school leadership team to discuss what you have learnt.

Make adaptions to schemes of work. Add diverse images and examples as a first step.

Reach out to local charities who work with refugees to set up links and share resources.

Set up Social Emotional Learning clubs using the IRC’s Games Bank and Lesson Plan Bank, days or assemblies to introduce the topic to your school.

Consider practical changes that can be made instantly in your school.

Consider the needs of refugee families:

Can your school offer English classes?

Can staff/parents donate items needed for a new families’ homes?

Can school pay for uniforms if the family cannot afford them or donate good quality second-hand uniforms?

Schools should translate all key documents and staple them to original forms so families can know what needs to be completed and how. Sit with families while they fill out important forms rather than sending papers home which may not be understood.

The IRC maintains a strong commitment to supporting teachers throughout the UK. We recognise that for many newly arrived children school can often represent the only sense of normality and routine in their lives and that teachers are a fundamental part of helping them to recover and thrive.

We regularly update our website with new resources and hold monthly meetings where we invite guest speakers to share their expertise and experience. You can also request a 1-1 follow up call with one of our team to talk through your situation and provide tailored advice. You can find all this information and more on the Healing Classrooms UK website.

And finally, thank you for taking the time to complete this training and for your commitment to supporting refugee and asylum-seeking children and youth in the UK. Do not underestimate the impact a few small changes can have on a young person’s life.

Moving on

References

Bell Foundation. (2022) The Effective Teaching of EAL. Available at: https://www.bell-foundation.org.uk/eal-programme/ guidance/effective-teaching-of-eal-learners (Accessed 26 June 2025).

Dryden-Peterson, S. (2018) 'Inclusion of refugees in national education systems', UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266054.locale=en (Accessed 26 June 2025).

Hammond, Z. (2014) 'Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain', Corwin Publishers, USA.

Morrison, N. (2014) How schools are breaking down the language barrier for EAL students. Available at: https://www. theguardian.com/teacher-network/teacher-blog/2014/mar/05/teaching-eal-foreign-languages-students-integration-schools (Accessed 26 June 2025).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the real children and families whose stories inspired these case studies and all of the past participants who have shared their examples of good practice which have all helped feed into this course.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Important: *** against any of the acknowledgements below means that the wording has been dictated by the rights holder/publisher, and cannot be changed.

574048: Shukria Rezaei

574049: Adapted from noomtah/Flaticon

574051: Dashqin Huseynaliyev/Alamy

574050: Adapted from Deni/ Adobe stock

574052: Adapted from Huticon/Shutterstock

574055: Adapted from Freepik on Flaticon

574056: Adapted from COOL STUFF/Shutterstock

574057: Adapted from jihad/Shutterstock

574058: Adapted from Emil Mahsumov/Shutterstock

572934: Adapted from Kateryna Fedorova Art/Shutterstock

580013: Mariia Bashynska and Veronika Maksymiuk

574088: strichfiguren.de/ stock adobe

572932: Wirestock Creators/Shutterstock