Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 21 February 2026, 1:20 PM

Unit 4 50 shades of humour

Introduction

Welcome to Unit 4, ‘50 Shades of humour’. This unit explores the various functions and impacts of humour in online meetings.

After our welcome audio, you will learn about how humour is used and experienced in online interactions and how this relates to gender and other hierarchies in the workplace. The unit includes some activities, including videos where humour is used in different ways, followed by a reflection on your own experiences and use of humour. The unit will end, as usual, with a short quiz to check your learning.

Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

By the end of this unit, you should be able to:

- Understand how humour can be used in different ways in online meetings to promote effective and equitable online meetings.

- Understand that humour can be experienced in different ways.

- Develop the skills to identify how humour is being used to facilitate or hinder equitable interactions.

- Reflect on potential responses when humour is being used in positive and negative ways.

Welcome from the Unit 4 authors

Listen to one of the unit authors, Katrín Ólafsdóttir, introducing herself and sharing what she enjoyed most about the GEiO research project.

Note: In the audio below the author speaks in her first language. The transcript has been translated into English.

Next, go to 1 Humour at work.

1 Humour at work

Humour is a social phenomenon that people use to influence social settings. In the workplace, it often serves to help build relationships with colleagues and teams, so it can be a great tool for creating a sense of community and relieving stressful situations. However, it can also reinforce hierarchies by, for example, undermining junior colleagues, and can even become a means of bullying (Holmes and Marra, 2006; Kotthoff, 2022; Ólafsdóttir, Petúrsdóttir and Rúdólfsdóttir, forthcoming; Taylor, Simpson and Hardy, 2022).

Humour can serve many functions and it affects people differently – recipients as well as those who witness the humorous interaction. It can be used and experienced both positively and negatively (Holmes and Marra, 2006; Taylor, Simpson and Hardy, 2022).

Activity 1 What do you already know about humour at work?

Activity 1 What do you already know about humour at work?

Did you know that the lower a person’s status in the workplace, the more likely they are to laugh at a joke made by someone with a higher status? And that individuals with lower status are more likely to make a joke at their own expense?

Spend a moment thinking about why that might be and jot down some notes.

Feedback

The way humour is experienced can be quite different from how it was intended, and workplace hierarchies and other factors can influence the use of humour and how jokes are taken. For instance, it is often safer for lower status colleagues to make jokes at their own expense to avoid challenging workplace hierarchies. At the same time, a high-status colleague can do the same to minimise the difference in status.

This was just a short activity to get you thinking about the topic. In the next section we’ll draw on the existing research to explore things further.

2 Humour in online meetings

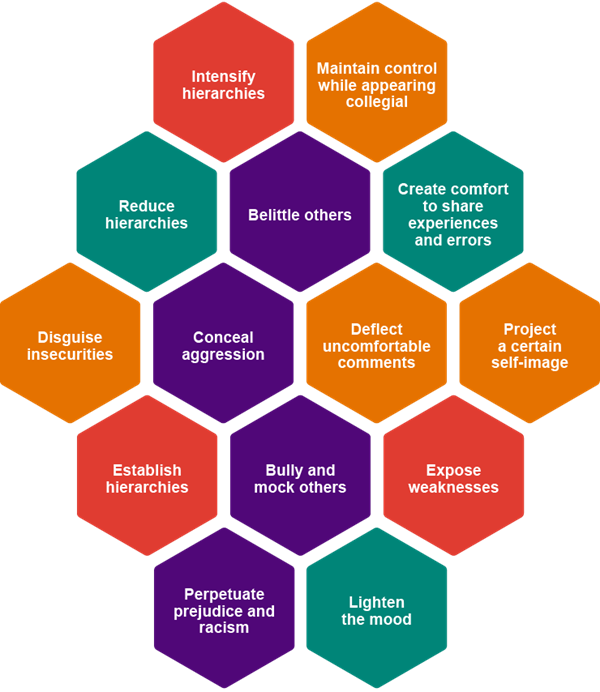

As you will know from experience, humour can affect the dynamics in online meetings. In Unit 3 you read about how the chair will often set the tone of a meeting, using humour to either intensify or reduce already existing hierarchies (Taylor, Simpson and Hardy, 2022).

By poking fun at their own abilities or making a humorous remark about a mistake, a chair can lighten the mood. By sharing their experiences and errors, they can encourage other participants to feel more comfortable (Holmes and Marra, 2006; Taylor, Simpson and Hardy, 2022). However, humour can also be used to help disguise insecurities by making light of one’s shortcomings in an attempt to ward off criticism from others (Holmes and Marra, 2006; Tabassum and Karakowsky, 2023).

Meeting participants can use socially accepted excuses in humorous ways to hide that they made a mistake or forgot to prepare something for a meeting (Holmes and Marra, 2006). Socially accepted excuses are dependent on the context, but may include having a child who is unwell, being held up due to a delay on public transport, or not having had your morning coffee. Leaders can use these excuses to distract from an error they’ve made and then use humour to reduce the embarrassment of admitting a mistake (Holmes and Marra, 2006). For colleagues with a lower status within an organisation, it is often safer to make a joke at their own expense so as not to challenge the workplace hierarchy (Kotthoff, 2022).

Humour can also be used to project one’s self-image, like when a more senior staff member wants to seem down-to-earth and ‘one of us’. At the same time, humour can help those in higher positions maintain control in online meetings while appearing collegial (Holmes and Marra, 2006; Kotthoff, 2022). For instance, giving an unwelcome instruction or request in a jokey way to minimise the unpleasant fact that refusal is not an option: ‘And as a special treat, lucky James will get to stay late to proofread and format the report’. Therefore, hierarchies, and power, can be established and reinforced through the use of humour (Downing, Marriott and Lupton, 2021; Karl, Peluchette and Aghakhani, 2022).

Figure 1 shows some of the effects of humour or ways that humour can be used. Some of these examples may be intentional or unintentional. Have a look – can you think of occasions when you have used, witnessed or been the recipient of any of these?

As discussed in Unit 2, some communication styles can negatively impact interactions in online meetings. If humour is used as a tool to mock or bully others, and if excessive mockery is directed at one person more than others, or if humour is used to belittle someone based on their gender, age or ethnicity, this humour will be experienced as aggressive (Kotthoff, 2022; Ólafsdóttir, Petúrsdóttir and Rúdólfsdóttir, forthcoming; Taylor, Simpson and Hardy, 2022). Humour can conceal the aggression behind a joke (Grugulis, 2002). This makes it difficult for the target to argue that it was offensive, as the typical response would be that it was ‘just a joke’ (Kotthoff, 2022).

Making fun of another’s abilities, belittling them, making jokes at their expense, or humorously exposing their weaknesses to a group is bullying. Moreover, this behaviour is detrimental, not only to the colleagues but also to a collegial and equitable work culture (Kotthoff, 2022).

2.1 Gender and humour

Have you ever noticed a gendered pattern in workplace humour? As we've discussed, who you are and your identity can affect how you use and experience humour, and you won’t be surprised to hear that gender plays a significant role in this context.

In group settings, men tend to make more jokes, while women are more likely to laugh at jokes that are made by others (Kotthoff, 2022). You may recall we mentioned above how this is also a pattern with higher and lower status colleagues. When women want to be funny, they often make jokes to lighten the mood or come across as collegial. Men's humour, however, tends to be more challenging and direct (Taylor, Simpson and Hardy, 2022). The gendering of meetings closely relates to gender stereotypes of abilities and skills (Dhawan et al., 2021; Pétursdóttir, 2009). As we saw in previous units, while women are often perceived as naturally suited to communication and caring roles, men are more often associated with leadership and technical capabilities (Dhawan et al., 2021; Pétursdóttir, 2009). This can be explained by societal expectations for women and men – how they are supposed to behave and act with regard to their gender (Williamson, Taylor and Weeratunga, 2024).

When it comes to sexist humour, women generally find it to be more offensive than men do (Tabassum and Karakowsky, 2023). Unsurprisingly, individuals with sexist attitudes tend to see it as perfectly acceptable (Kotthoff, 2022).

Interestingly, even senior women in leadership roles use humour to downplay their own abilities and express their frustrations, just as more junior members of staff often will, as this strategy helps them navigate the often tricky waters of gender stereotypes (Kotthoff, 2022). This allows them to be the boss but still come across as feminine.

Another gendered aspect of leadership is that technical issues in online meetings tend to reflect more negatively on women than men. This is because gender stereotypes encourage us to think women will be less technically able (Dhawan et al., 2021). It also taps into the societal expectations we mentioned above that women are good at caring and communication, while men are better leaders with technical abilities (Dhawan et al., 2021; Pétursdóttir, 2009).

2.2 Responding to humour

It is important to recognise that someone’s ability to respond to humour, particularly when it is aggressive, is shaped by both their position within the company hierarchy and their social identity characteristics such as gender, race, ethnicity, class and age (Taylor, Simpson and Hardy, 2022). These power dynamics can significantly limit someone's options for responding – a junior employee may feel unable to push back against a senior colleague's inappropriate joke, even if it causes discomfort (Kotthoff, 2022).

Challenges like these are even more pronounced in online environments, where the limits of videoconferencing can make it harder to respond effectively to humour (Williamson, Taylor and Weeratunga, 2024). It is harder to read subtle body language online, there are timing issues caused by audio delays, and it can be a challenge to follow multiple small screens (Karl, Peluchette and Aghakhani, 2022; Standaert, Muylle and Basu, 2021). All these intensify the existing power imbalances that already make it difficult to respond to workplace humour.

Although one may develop strategies to minimise or deflect jokes perceived negatively by, for instance, turning off the camera, thereby using the online environment as a shield (Gerpott and Kerschreiter, 2022; Ólafsdóttir, Petúrsdóttir and Rúdólfsdóttir, forthcoming; Karl, Peluchette and Aghakhani, 2022), managing these requires significant effort and time that could be used more productively (Pétursdóttir and Rúdólfsdóttir, 2022). Often, laughing along can be a useful way of dealing with aggressive humour, while in other situations, humour can be employed to ‘call out’ the person who initiated the joke (Ólafsdóttir, Petúrsdóttir and Rúdólfsdóttir, forthcoming). For instance, exaggerated saluting to allude to military discipline if the chair is using humour to be ‘bossy’. This response could come from the target of the humorous remark, but also the other participants in the online meeting (Standaert, Muylle and Basu, 2021). It is interesting to observe who laughs along, when, and with whom, as this can provide insight into power dynamics within online meetings and hierarchies in companies.

Company hierarchies can also impede the reporting of aggressions that are disguised as humour. Research shows that personal attributes can exaggerate the impact of this (Tabassum and Karakowsky, 2023). Employees in lower positions, women, disabled people, and other marginalised employees are less likely to report aggressions in general but particularly when the aggression is masked as a joke (Tabassum and Karakowsky, 2023). The humorous context of the aggression makes it harder to prove its aggressive intent (Kotthoff, 2022). To address this, organisations should support equity and inclusivity in the workplace, as in these organisations, women and other minoritised groups feel more confident to report and challenge aggressive humour.

Similarly, as you saw in Unit 3, during online meetings, chairing practices such as empathetic and respectful communication can foster more inclusive meeting environments where employees feel comfortable speaking up.

3 How humour is used in online meetings

So far this unit has covered the various ways in which humour can be used in online meetings, how gender and humour interact and how responding to humour can depend on company hierarchies and personal attributes. In this activity you will work through some videos where humour is used in online interactions and consider some of the implications.

Activity 2 Examples of how humour is used in online meetings

Activity 2 Examples of how humour is used in online meetings

Part 1 – Using humour in a positive way

Watch Video 1 below without interruption.

Transcript: Video 1 Using humour in a positive way

Now you have watched the video once, watch it again with these questions in mind:

Part 2 – Using humour in a less positive way

Watch Video 2 below without interruption.

Transcript: Video 2 Using humour in a less positive way

Now you have watched the video once, watch it again with these questions in mind:

Part 3 – Using humour in an aggressive way

Watch Video 3 below without interruption.

Transcript: Video 3 Using humour in an aggressive way

Now you have watched the video once, watch it again with these questions in mind:

Having watched the videos, we hope you will have gained further insight into the positive and negative ways humour can be used in online meetings. The flip cards explored those situations in more detail to support your interpretation of the videos. They highlight how company hierarchies and factors such as gender influence the use, perception and response to humour.

4 Time for reflection

Now it is time to reflect on what you have learned so far and relate it to your own experiences. In the following activity, you will receive prompts to help you reflect on your learning in this unit so far and particularly on the videos.

Activity 3 Connecting what you’ve learned to your own experiences

Activity 3 Connecting what you’ve learned to your own experiences

This session explored how humour shapes power dynamics in online meetings. It can be a powerful tool to either reduce or reinforce hierarchies. When used positively, humour can lighten the mood, defuse tension or make people feel more comfortable sharing mistakes. Chairs, in particular, can use humour to set a welcoming tone and encourage openness.

Humour can also be used to belittle others, conceal aggression, or maintain control while appearing friendly. It can also reinforce hierarchies, especially when used by those in senior roles. In these cases, it may perpetuate stereotypes and even prejudice.

You also looked at how humour is gendered. Research indicates that men tend to make more jokes, often in a direct or challenging style, while women are more likely to laugh along or use humour to build connections. These patterns reflect and reinforce broader stereotypes about gender roles and authority in the workplace.

Reflection is an important tool. It is useful to understand when humour is being used in a positive way or if it has been used to cause discomfort or offend others. Everyone has experienced occasions when things are said that may not be perceived the way they were intended. Reflection helps us work out how this has happened. In a workplace where equality is emphasised and sexism is condemned, it is important to also pay attention to our own behaviours.

Next, think about the varying social identities and how they may interplay with the different uses of humour in online meetings and work through the reflective questions in Activity 4.

Activity 4 Reflecting on your own use of humour in online meetings

Activity 4 Reflecting on your own use of humour in online meetings

Read through the next subsection which takes you through workplace humour and covers best practice for navigating this in online meetings.

4.1 Best practice – navigating workplace humour through an intersectional lens

Now that you have reflected on your own use and reception of humour, this section will provide you with an overview of best practices for creating an inclusive environment. These recommendations consider how people’s social identities and their roles within the workplace shape their experience of humour at work. They are based on what you have learned so far in the course and the most recent research in this area. The goal is to foster an inclusive environment where everyone can contribute effectively.

While you can develop your own skills in navigating workplace humour, your employer also has a role and should provide clear meeting guidelines and safe reporting processes. If your workplace does not provide any of this, consider discussing it with your manager. Below are three practical steps you can use as tools to foster a more intersectional awareness and develop your own responses and uses of workplace humour. Choose strategies that best suit your situation, capacity, safety considerations, and the specific context as you help create positive change.

Step 1: Building awareness on a daily basis

It is important for you to regularly consider your own social identities and position in the company and reflect on it in connection with the people you work with. Your position in relation to others changes rapidly depending on who you collaborate with and who you are meeting, etc. You can also encourage your colleagues to reflect on their social identities and roles within the workplace.

Discussing these topics during lunch breaks can be engaging. This can support the promotion of positive humour and help prevent negative humour that could be perceived as aggressive. You can use the assessment below to regularly reflect on your own use of humour in online meetings.

Mindful humour assessment

- What is my position in the company's hierarchy?

- What are my social identities?

- The last time I used humour in an online meeting, why did I make this joke?

- How did people react? Did they really laugh or just laugh along?

- Considering the Social Identity Wheel and company hierarchies, how do I relate to the person I directed this joke towards?

- Thinking about the last time someone made a joke during an online meeting at someone else, how did I react?

- Considering the Social Identity Wheel and company hierarchies, who was the recipient of this joke?

- Thinking about the last time I was the recipient of humour, who made the joke? How did it make me feel?

Step 2: Applying awareness in online meetings

The reflections on your social identities and position in the company are useful when entering online meetings, as they help you navigate your use and reception of humour. In this step, you shift from focusing on yourself to understanding the dynamics of the online meeting. Keep in mind that online meetings can mask or highlight certain aspects in comparison to in-person meetings, such as different cultural communication styles, visible and invisible aspects of identity, reading facial expressions and body language and technical accessibility issues. Try to understand others’ social identities and company roles, and how your position relates to them, as this influences the meeting dynamics and how humour is used and perceived.

Mindful online meeting assessment

- How do I relate to others in this meeting, considering the Social Identity Wheel and company hierarchies?

- Who is the chair of the meeting, and what is their role in the company’s hierarchy?

- Who is welcome to speak? Who is comfortable speaking? Who does not speak?

- Considering the Social Identity Wheel and company hierarchies, how do the different positions of the participants influence their ability to actively participate in the meeting?

Step 3: Practical skills to change meeting cultures in the workplace

By fostering intersectional awareness on a daily basis in both online and in-person meetings, you can positively impact meeting culture. Steps 1 and 2 should help you explore how intersectionality enables you to examine meeting spaces and create more inclusive environments in videoconferencing. Step 3 provides you with practical tools to navigate aggressive and negative humour. You can consider these response strategies based on your situational assessment.

Unit 4 conclusion

Humour in the workplace can do many things, including fostering community and relieving stress, but it can also reinforce hierarchies and contribute to bullying. The humour that is experienced can vary depending on the context and different identities, such as gender, race, class and socioeconomic status. This session has shown how these variations are not random – workplace humour operates as more than simple entertainment. It’s a complex social mechanism that both reflects and reinforces existing power structures.

The evidence shows that factors like gender, race and age, together with existing organisational hierarchies can significantly influence both how humour is deployed and how it can be received. Online environments amplify these dynamics in ways we are only beginning to understand, creating new challenges for reading social cues and responding appropriately.

Rather than viewing humour as inherently positive or negative, the research we have looked at throughout this unit suggests we should recognise it as a powerful workplace force that deserves thoughtful attention. Understanding these dynamics allows us to be more aware of the power dynamics in the workplace, be it as an observer, the joker or as the target of the joke.

Unit 4 practice quiz

Now have a go at the Unit 4 practice quiz – you can attempt the quiz as many times as you like.

After you have completed the Unit 4 quiz, move onto Unit 5 Could this meeting be an email?

References

Dhawan, N. et al. (2021) ‘Videoconferencing Etiquette: Promoting Gender Equity During Virtual Meetings’, Journal of Women’s Health, 30(4), pp. 460–465. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8881 (Accessed: 14 July 2025).

Downing, L., Marriott, H. and Lupton, D. (2021) ‘“'Ninja' levels of focus”: Therapeutic holding environments and the affective atmospheres of telepsychology during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Emotion, Space and Society, 40, 100824. Available at: 10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100824 (Accessed: 26 August 2025).

Gerpott, F. H. and Kerschreiter, R. (2022) ‘A Conceptual Framework of How Meeting Mindsets Shape and Are Shaped by Leader–Follower Interactions in Meetings’ Organizational Psychology Review, 12(2), pp. 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/20413866211061362 (Accessed: 26 August 2025).

Grugulis, I. (2002) ‘Nothing Serious? Candidates’ Use of Humour in Management Training’, Human Relations, 55(4), pp. 387–406. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726702055004459 (Accessed: 26 August 2025).

Holmes, J. and Marra, M. (2006) ‘Humor and leadership style’, HUMOR, 19 (2), pp. 119–138. Available at: https://doi.org/doi:10.1515/HUMOR.2006.006 (Accessed: 26 August 2025).

Karl, K. A., Peluchette, J. V. and Aghakhani, N. (2022) ‘Virtual Work Meetings During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Good, Bad, and Ugly’, Small Group Research, 53(3), pp. 343–365. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/10464964211015286 (Accessed: 26 August 2025).

Kotthoff, H. (2022) ‘Gender and humour: The new state of the art’, Linguistik Online, 118(6), pp. 57–80. Available at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.118.9084 (Accessed: 14 July 2025).

Ólafsdóttir, K., Petúrsdóttir, G.M and Rúdólfsdóttir, A.G. (forthcoming) ‘Gendered interactions in online meetings’.

Pétursdóttir, G. M. and Rúdólfsdóttir, A. G. (2022) ‘“When he turns his back to me, I give him the finger”: Sexual violations in work environments and women’s world-making capacities’, Journal of Gender Studies, 31(2), pp. 262–273. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1956443 (Accessed: 26 August 2025).

Pétursdóttir, G. M. (2009) Within the Aura of Gender Equality: Icelandic work cultures, gender relations and family responsibility: A holistic approach. PhD thesis. University of Iceland.

Standaert, W., Muylle, S. and Basu, A. (2021) ‘How shall we meet? Understanding the importance of meeting mode capabilities for different meeting objectives’, Information & Management, 58(1), 103393. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2020.103393 (Accessed: 26 August 2025).

Tabassum, A. and Karakowsky, L. (2023) ‘Do you know when you are the punchline? Gender-based disparagement humor and target perceptions’, Gender in Management: An International Journal, 38(3), pp. 273–286. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-01-2021-0026 (Accessed: 14 July 2025).

Taylor, S., Simpson, J. and Hardy, C. (2022) ‘The Use of Humor in Employee-to-Employee Workplace Communication: A Systematic Review With Thematic Synthesis’, International Journal of Business Communication, 62(1), pp. 106–130. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/23294884211069966 (Accessed: 26 August 2025).

Williamson, S., Taylor, H. and Weeratunga, V. (2024) ‘Working from home during COVID-19: what does this mean for the ideal worker norm?’, Gender, Work & Organization, 31(2), pp. 456–471. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.13081 (Accessed: 26 August 2025).