Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 21 February 2026, 1:27 PM

Unit 3 Leading the way – effective chairing

Introduction

In Unit 2 ‘Being a participant’, you looked at how to be an effective participant in online meetings. In this unit you will learn about how to be an effective chair and discover ways to promote inclusivity and fairness in online meetings, ensuring the views of all are heard and respected. At the same time, you will consider how some chairing styles get in the way of inclusive practice.

As with the other units, you will extend your understanding of the Social Identity Wheel by thinking about it within the context of chairing.

Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

By the end of this unit, you should be able to:

Differentiate between effective and ineffective chairing practices.

Compare and contrast different chairing styles, i.e. participative and directive leadership styles.

Discuss how social identity influences meeting dynamics and participant responses to the chair.

Identify chairing practices that encourage and hinder inclusive participation within online meetings.

Implement chairing practices that promote inclusivity within online meetings.

Welcome from the Unit 3 authors

Listen to the unit authors introducing themselves and sharing what they enjoyed most about the GEiO research project.

Note: In the audios below the authors speak in their first language. The transcript has been translated into English.

Next, go to 1 Introducing the chair.

1 Introducing the chair

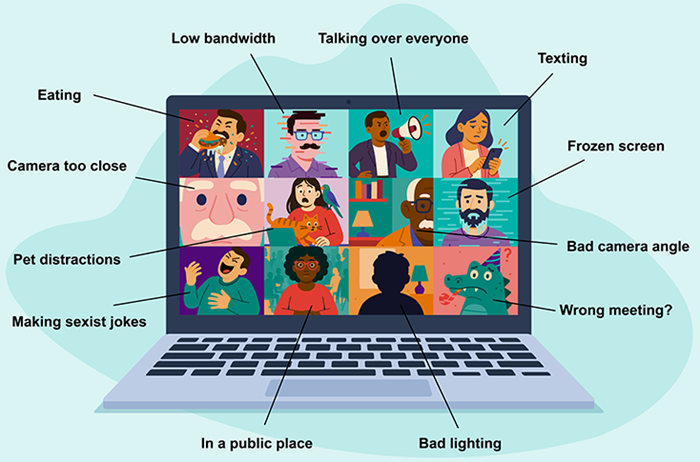

Have a look at the image above. You may recognise some, or all, of the issues represented here from your own experience of online meetings. These issues can be prevented or managed through effective chairing practices. In this section, you will distinguish between effective and ineffective chairing practices and styles.

1.1 Chairing practices

One way of thinking about chairing practices is to think about the rights and obligations that come with the role of chair.

Activity 1 The rights and responsibilities of chairing an online meeting

Activity 1 The rights and responsibilities of chairing an online meeting

Which of the following behaviours would you expect from a chair of an online meeting?

Decide:

- Yes

- No

- Maybe

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is b.

b.

The agenda should be sent well in advance to give participants enough time to prepare and raise points for discussion.

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is a.

a.

Communicate clearly what the purpose of the meeting is as people have given up their time to attend. Avoid the ‘let’s get this meeting over with as quickly as we can’ attitude.

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is c.

c.

While it’s great to have enthusiastic contributors, this shouldn’t be at the expense of the agenda. You could encourage comments in the chat box.

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is b.

b.

Some people may not want to contribute to the discussion but check with silent participants to make sure they don’t want to say something. Consider alternative methods of participating – e.g. chat boxes, polls, break-out room.

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is a.

a.

This is a key role of the chair. It’s a good idea to run through the ground rules for new participants, allowing any new suggestions.

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is b.

b.

Don’t wait until the end of the meeting to check your chat box as there may be too many comments. It is better to review as you go along.

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is c.

c.

On occasions, and if there is full consensus, this may be a viable option (especially during busy times). However, generally, this is not a good idea as it can discriminate against people who have other obligations outside work (e.g. parents, carers). Participants can reasonably expect to recoup the time spent on these meetings.

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is c.

c.

Some meetings are brief and there may not be time to receive feedback from everyone. However, research suggests eliciting input from others can help boost positive meeting outcomes.

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is a.

a.

The chair should manage the order and pace of the meeting and ensure enough time for feedback during and at the end of the unit.

a.

Yes

b.

No

c.

Maybe

The correct answer is b.

b.

It is the chair’s job to make sure all items on the agenda are given enough discussion time. Although it is important to include input from participants, it’s also important to manage timings.

How did you do?

It’s likely you found it quite straightforward to identify the duties of a chair. Of course, meetings can and do vary in form and function. Organisational culture, participant status, topic and meeting context can all influence the way a meeting develops. Yet, despite these differences, research indicates that participants have a shared understanding of how meetings ‘should’ operate (see Angouri and Marra, 2010). This includes chairing practices such as opening and closing meetings and how speaking turns are managed.

So, despite differences in corporate culture there are striking similarities in the expectations placed on chairs and the ways in which chair roles work.

1.2 Chairing as leadership

Since COVID-19, the number of online work meetings has multiplied (Standaert, Muylle and Basu, 2022). For many, this has resulted in too many unnecessary work meetings, with little structure or understood purpose, leading to the often-used question, ‘could we do this in an email?’ (see Unit 5 of this course).

However, under effective leadership, work meetings can be an important resource for an organisation, facilitating strong discussions that elicit a range of opinions and produce high-quality decisions (see Mroz, Yoerger and Allen, 2018). The way a chair interacts with other participants sets the tone for what is considered appropriate communicative behaviour. The position of chair is one that requires considerable organisation and communication skill to manage the different interests present within the meeting while also holding the interests of the organisation and managing their own identity as leaders (Rogerson-Revell, 2011).

Chairing styles

Depending on the context of the meeting, there is a great degree of flexibility in the way chairs carry out their role. Factors such as meeting purpose, topic, formality and participant relations all influence the way chairing is carried out.

Much of the literature around chairing practice identifies two predominant styles of chairing leadership. These will be referred to as ‘participative’ and ‘directive’ chairing. Table 1 below summarises the main features of each style, along with their corresponding positive and negative effects.

Participative chairing

| Directive chairing

| |

|---|---|---|

| Features |

|

|

| Positive and negative effects |

|

|

Of course, it’s easy to stereotype chairing styles and think about them in binary terms. There are many different forms and functions of meetings, which may require different styles of chairing. The reality is that effective chairs draw on different styles depending on what is appropriate or required for the given meeting.

So far, you have considered different aspects of chairing styles and practices. In Activity 2, you will consolidate this learning by reviewing some of the examples of effective and ineffective chairing practices.

Activity 2 Reviewing chairing practices – how not to chair a meeting

Activity 2 Reviewing chairing practices – how not to chair a meeting

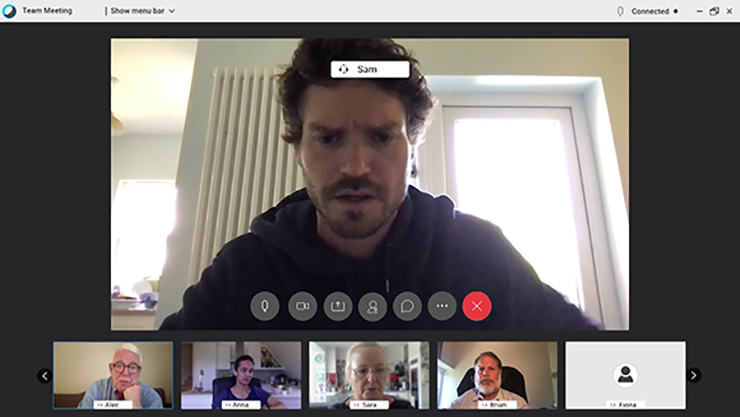

Watch Video 1 through once in full and then a second time while you make notes.

Transcript: Video 1 How not to chair a meeting

Make use of your learning on this course so far, and your own experiences of online meetings, and write down the examples of ineffective chairing you have noticed in the box below:

Discussion

Some of the ineffective practice examples are noted below – you may have noticed other examples too.

The chair:

- Is late. Being late is disrespectful to others and limits opportunities to fix any technical issues.

- Is unprepared.

- Dresses very casually and has stains on their hoodie.

- Is not clear to everyone due to poor lightning. This can disadvantage some participants e.g. those people who lipread.

- Doesn’t ask people to turn on their cameras at the start.

- Starts the meeting without an introduction and participants are given no time to ‘arrive’.

- Has not checked their microphone is working.

- Shows a lack of respect for Anna – is impolite to her and interrupts her.

- Did not send an agenda.

- Does not interrupt Alec when they keep talking for too long.

- Does not use professional language.

- Uses jokes or irony in the wrong situation.

- Does not prioritise raising an important topic 10 minutes before the end of the meeting.

- Asks Sarah for an opinion on the applications without giving her the chance to prepare.

- Interrupts Sarah several times disrespectfully during the discussion about the applications.

- Asks two people who remained silent for contributions after the end of the meeting.

- Does not check the chat box throughout the entire meeting.

- Shows little respect for others’ time – e.g. the meeting ends 10 minutes late.

Now that you have had a chance to consider different approaches to chairing and reflected on some of the problematic features, we’ll move on to some of the issues that can impact good and bad chairing.

2 Online meetings and social identities

In the previous section, you covered some features of best practice when chairing an online meeting and some different approaches to chairing.

In this section you will learn about how social identity influences meeting dynamics. Drawing on the Social Identity Wheel, you will consider how social identity influences the chair’s and participants’ experiences of being in a meeting. After this you will look at intersectionality and its relevance to the role and identity of the chair.

2.1 Analysing your online meeting experiences

Using the Social Identity Wheel, think about how your participation in meetings, either as a participant or as chair, is affected by your social identities. Activity 3 will guide your thinking around this.

Activity 3 Reflecting on your experiences of social identity in online meetings

Activity 3 Reflecting on your experiences of social identity in online meetings

Use the box below to write down your reflections on the following questions:

- Which of the identities are you most aware of about yourself (if any), when you attend an online meeting?

- Which of your identities, do you believe, have the greatest effect on how others perceive you?

- Do any of your identities support your participation in online meetings and do any hinder your participation?

- Can you think of any challenges that a chair might face in relation to their social identities?

Answer

There are no right or wrong answers here as this activity is an opportunity for reflection.

- Thinking about social identity can highlight how some identities are normalised within some contexts. For example, if you are a team member whose first language is not English you may have to work really hard to participate in meetings where everyone else speaks English as their first language. If you are someone who speaks English as a first language, you are less likely to have to think about your language within these contexts.

- Identities that are normalised can be understood to be privileged. When aspects of your identity are the norm, you are less likely to be confronted by them than when they diverge from the norm.

- Some identities are visible (race, gender) while others are not visible (some disabilities, religion, sexual orientation).

- People may choose to conceal some aspects of their identity for fear of discrimination or to avoid negative perceptions. For example, if you are in a same-sex relationship and haven’t shared this with everybody at work, it might be difficult for you to share that you are meeting up with your partner’s family in a discussion about weekend plans at the beginning of a work meeting.

- You may choose to reveal aspects of your identity in some contexts but not in others. For example, you might tell your family and friends you are neurodivergent but choose not to disclose that at work.

- Social identities are not static. Some social identities you may hold your whole life, while others may change throughout your life.

- The social identities that are prominent for you in online meetings are probably similar to the ones that are prominent for you in in-person meetings. However, some might be amplified. For example, a d/Deaf person might find it difficult to follow conversations if they rely on lip reading. Your social class might be more visible in online meetings as your home environment might be on display. If you divide your time between work and caring responsibilities, then your identity as a carer might be more visible if working online from home.

- The identity of chair confers certain institutional privileges (e.g. the right to open and close meetings). However, the chair may not be privileged in other aspects. Social identities are embedded within wider social and societal power relations and less privileged aspects of identity may coexist with privileged ones.

2.2 When the chair is a woman

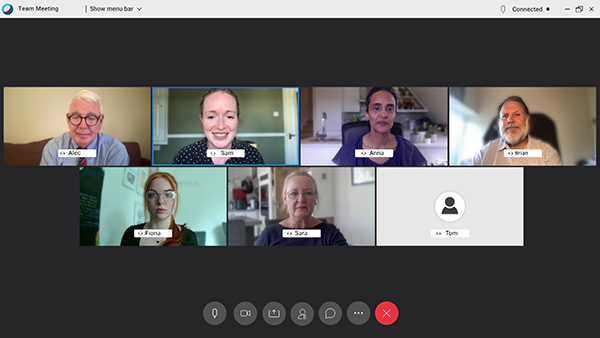

Chairing styles are shaped by factors such as the format of the meeting (e.g. whether it is a talk or a presentation), the type of meeting (entirely online or hybrid) and how familiar participants are with one another (Sarkar et al., 2021). It’s important to consider that participants also shape the way a chair carries out their role. Imagine you are chairing the meeting above – how do the expressions on the attendees' faces impact how you might feel and affect how you carry out your role?

It is likely that you would be affected negatively by the non-verbal communication of those online participants, perhaps impacting on your ability to chair effectively or with confidence.

The performance of leadership is as much affected by the response of participants as by any personality traits of the chair. This is particularly important when the chair is someone whose social characteristics may be subject to discrimination and bias (such as gender, skin colour, sexuality, age, class).

In Unit 2, you learned about gender stereotypes and how these influence attitudes and expectations of participant behaviour within workplace meetings. Gender dynamics also play out in various ways when the chair is a woman (see Dhawan et al., 2021). Here are some findings from existing research on gender and chairing/leadership:

- Within in-person meetings, women are sometimes not recognised as chairs, despite them sitting at the head of the table (Porter, Geis and Jennings, 1983).

- When speaking, female chairs are more likely to receive negative facial gestures such as frowning and head shaking than male chairs (Butler and Geis, 1990).

- Female leaders generally receive more non-verbal evaluative responses (positive and negative) than male leaders (Koch, 2005).

- Female leaders who talk a lot are judged more harshly than male leaders who talk a lot and female leaders who do not talk very much (Brescoll, 2011).

- Female chairs within corporate environments can find themselves in a double bind; they are encouraged to adopt behaviours associated with masculine leadership in management training courses (e.g. general assertiveness, speaking with authority, self-promotion) but are seen as controlling or aggressive when they do. Consequently, some women assume ‘invisibility’ when they are in leadership positions, seeking to reduce opportunities for interpersonal conflict with their work teams (Ballakrishnen, Fielding-Singh and Magliozzi, 2019).

Clearly, gender has an effect on people’s responses to chairs and therefore also affects the way chairing is performed.

The research above refers to in-person meetings. Online environments might be more equitable in some ways (e.g. the physical arrangement of online participants avoids having a ‘head of the table’) but online environments might amplify some negative responses. Online meetings might highlight and even support negative behaviours and facial gestures (see Dhawan et al., 2021).

What the research tells us is that the role and identity of the chair is relational, shaped as much by the responses and expectations of other people in the meeting as it is by the chair. It is important to recognise how people’s responses to the chair may be informed by discriminatory and biased opinions, and gender is just one characteristic that may be the subject of discrimination.

2.3 Intersectionality

You came across the concept of intersectionality briefly in Unit 2, Section 3.1. The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw and is an extremely useful one when thinking about any form of discrimination within the workplace (or anywhere for that matter). An intersectional approach is one that recognises that all people have more than one characteristic that may be subject to discrimination and hostility. For example, while a woman may experience sexism when chairing a meeting, a disabled woman of colour may also experience ableism and racism.

In this section you will start thinking about how the social identities of the chair impact the way they are responded to.

It is also the role of the chair to think about the social identities of those attending the meeting. The chair must ensure that they and all participants avoid acting in discriminatory or biased ways toward other attendees.

3 The importance of inclusive chairing

In the previous section, you learned about how social identity influences the experiences of online meetings for everyone. In this section, you will develop your understanding of how chairing practices can influence these experiences by encouraging or hindering inclusive participation.

First, you will check your understanding of some key terms related to equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI). Then you will consider ways in which chairs can promote inclusivity within online meetings, including the use of inclusive language.

3.1 What is meant by inclusion?

The terms equality, equity, diversity and inclusion often come as a package (e.g. EDI policies) but what is the meaning of each of these terms?

Activity 4 What do equality, equity, diversity and inclusion mean?

Activity 4 What do equality, equity, diversity and inclusion mean?

What do you understand by equality, equity, diversity and inclusion? Match the terms below to the correct definition (adapted from the United Nations, UN Global Compact, 2025).

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 3 items in each list.

Diversity

Inclusion

Equity

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.2. ______ is relational, it is about the experience of individuals and groups in the workplace. It is about feeling seen, understood and valued as an individual with a unique identity, skills and experience.

b.3. ______ recognises that each person has different circumstances, that historically, some groups of people have experienced discrimination and that reaching equal outcomes will not be achieved by treating everyone the same. The focus is on allocating resources and opportunities according to circumstance and need.

c.1. ______ often focuses on quantity and the representation of different groups in an enterprise. Within organisations, there will be a focus on equality of opportunity and treatment in access to employment, development, promotion and pay for a range of people.

- 1 = c,

- 2 = a,

- 3 = b

Answer

How did you do?

‘While diversity tends to focus on quantity, equity and inclusion are focused on quality’ (UN Global Compact, 2025).

Inclusion is not about simply tolerating differences, inclusion means actively ensuring that people feel welcomed, valued and respected for who they are. It means actively creating environments where everyone feels they are appreciated and can participate in whatever way they can.

Inclusion and equity at work involve ensuring as many people as possible can participate or be represented in work-based activities. In relation to chairing online meetings, this means being aware of what barriers there might be for attendees to participate.

3.2 Inclusion and participation in meetings

Besides being a human rights issue, inclusion benefits organisations. Inclusive practices at work and within meetings ensure maximum participation of all employees. This leads to the expression of a range of diverse points of view and thinking, which in turn leads to new insights and ultimately, helps organisations make better decisions. This corresponds with a participative style of leadership.

However, despite most organisations having EDI policies, research indicates participation and barriers to participation within meetings can still be problematic for certain groups:

What the research shows:

- Men speak for longer periods of time than women in meetings (Wang and Roubidoux, 2020).

- Women experience numerous negative interruptions (Krivkovich et al., 2024).

- In some professional contexts, women are more likely to be introduced by first name than by professional titles compared with their male counterparts. This reinforces gender hierarchy and may impact negatively on performance (Dhawan et al., 2021).

- Younger women find it difficult to be heard in meetings and use the chat function more for participating (Sarkar et al., 2021).

- In science and medical contexts, even in gender-balanced rooms, men ask up to 80% more questions than women (Howe et al., 2023).

- At medical conferences, when men ask the first question, women ask proportionately fewer subsequent questions. Barriers to asking questions include ‘not being able to work up the nerve’ (Howe et al., 2023, p. 4).

- Across 20 UK-based medical conferences, only 10% had an equal balance of speakers from white ethnic groups versus those from any other ethnic groups (Howe et al., 2023).

- Having more diversity on panels at conferences might lead to increased participation from females and ethnic minorities in the audience (Howe et al., 2023).

- Disabled people within the workplace experience barriers to participation due to inaccessible technologies, e.g. technologies not compatible with assistive technologies (Alharbi, Tang and Henderson, 2023).

- The responsibility of sorting out accessibility falls on disabled people rather than organisations (Alharbi, Tang and Henderson, 2023).

- A barrier to disabled people’s participation in online meetings is the extra work required to be able to participate (e.g. processing parallel sources in multiple modalities can be challenging for people with a sensory disability) (Sarkar et al., 2021).

4 The importance of inclusive language

The use of inclusive language is really important for fostering a respectful and fair working environment. Inclusive language shows a commitment to avoiding discrimination and (un)intentional biases and ensuring people don’t feel excluded or marginalised in any way. It also promotes an inclusive culture, shaping what is acceptable within the meeting and also within the organisation.

It’s the responsibility of the chair to use inclusive language and to call out inappropriate language. It is recommended that you look to your organisation’s guidance on inclusive language.

The example in Activity 5 focuses on gender to exemplify the importance of inclusive language in meetings.

Activity 5 Language and gender

Activity 5 Language and gender

With regards to gender, most EDI policies/frameworks refer to concepts such as gender-discriminatory, gender-neutral and gender-sensitive language. Read the following definitions, then complete the multiple choice activity underneath.

- Gender-discriminatory language includes language that promotes stereotypes or demeans or ignores any person based on their gender.

- Gender-neutral language is a way of talking about people without assuming or specifying their gender. For example, avoiding language which can be interpreted as biased, discriminatory or demeaning by implying that one gender is the norm – e.g. using ‘people’ instead of ‘men’ as the default.

- Gender-sensitive language respects the diversity of gender identities. It promotes gender equality by addressing all people as individuals of equal value, dignity, integrity, and respect. In some contexts, however, it is important to identify gender, for example, when describing relative (dis)advantage.

Choose the correct term to identify what the following sentences are examples of:

a.

Gender-discriminatory language

b.

Gender-neutral language

c.

Gender-sensitive language

The correct answer is b.

b.

Gender-neutral language as it used the term ‘people’ which is inclusive.

a.

Gender-discriminatory language

b.

Gender-neutral language

c.

Gender-sensitive language

The correct answer is b.

b.

Some people assume that an engineer is a man. It is important to avoid indicating that bias in language by using the neutral pronoun ‘they’.

a.

Gender-discriminatory language

b.

Gender-neutral language

c.

Gender-sensitive language

The correct answer is a.

a.

Gender-discriminatory language as it excludes non-binary people.

a.

Gender-discriminatory language

b.

Gender-neutral language

c.

Gender-sensitive language

The correct answer is c.

c.

In some contexts, it’s important to acknowledge the relevance of gender, especially regarding issues of relative disadvantage.

a.

Gender-discriminatory language

b.

Gender-neutral language

c.

Gender-sensitive language

The correct answer is a.

a.

The stereotype assumption here is that a secretary is a woman.

a.

Gender-discriminatory language

b.

Gender-neutral language

c.

Gender-sensitive language

The correct answer is a.

a.

It is important to refer to women in their own right and not in relation to men. Better to say ‘Psychology researchers, John and Sarah contributed an interesting article to the journal’.

Gender-neutral and gender-sensitive language are sometimes used interchangeably (with gender-neutral language being considered an example of gender-sensitive language). They have been separated here to illustrate that sometimes it is necessary to identify a particular gender.

5 Inclusive practice: chairing skills for online meetings

Now you’ve covered the fundamentals of effective chairing, in this section you will review what you have learned and add further inclusive chairing skills to your practice.

Ensuring inclusive online meetings

Some of the key aspects of chairing an inclusive online meeting are summarised below. Click on the cards below to reveal some ideas – do you have any other ideas?

This is not an exhaustive list of considerations, but hopefully it highlights how many things a chair has to keep in mind before, during and after a meeting.

Now you have thought about inclusivity in online meetings, the next activity looks at all the various factors involved in effective chairing practice and how to chair a productive and inclusive online meeting.

Activity 6 Leading the way

Activity 6 Leading the way

Watch Video 2 through once without interruption, then a second time while you make notes.

Transcript: Video 2 Leading the way

The second time you watch it note down all the examples of effective chairing practice you notice in the box below:

Answer

Some noticeable effective chairing actions are listed below. Do you agree with them and would you add any others?

The chair:

- Tests the meeting software and their devices ahead of the meeting.

- Makes sure that their video setting is up and especially that there is a bright light. This ensures that every participant can see them properly on the screen in case lip-reading is needed.

- Has sent around a structured agenda ahead of the meeting.

- Is dressed professionally.

- Opens the meeting with some short small talk, giving everyone the chance to arrive.

- Asks people to put their camera on, if possible.

- Shows empathy.

- Sets boundaries/rules around the meeting.

- Politely interrupts Alec when he starts talking too much.

- Makes sure the debate is going into the right direction.

- Keeps to time and covers all important points of the meeting.

- Calms the debate down when necessary.

- Starts to wrap up the meeting 10 minutes before the announced end.

- Sums everything up at the end.

Unit 3 conclusion

In this unit you have differentiated between effective and ineffective chairing practices and learned about the differences between participative and directive leadership styles. Although there can be benefits and drawbacks of each depending on the context and function of the meeting, a participative style of leadership contributes to a more inclusive experience for everyone at the meeting.

You read through research showing that participation in meetings is impacted by social identities, with some groups of people being less likely to participate than others. Social identities also impact on the way the chair is responded to, with research showing that female chairs are judged more harshly than male chairs. The concept of intersectionality is a useful one for thinking about how multiple social identities interact to produce unique experiences of discrimination.

Inclusive chairing means having an awareness of the range of social identities within meetings and ensuring that the views and contributions of all are invited and valued. You have learned that some chairing practices promote inclusive participation, like using inclusive language, and some discourage it.

Now move on to complete the unit by checking what you've learned in the Unit 3 practice quiz.

Unit 3 practice quiz

Now have a go at the Unit 3 practice quiz – you can attempt the quiz as many times as you like.

After you have completed the Unit 3 practice quiz move onto Unit 4 50 shades of humour.

References

Alharbi, R., Tang, J. and Henderson, K. (2023) ‘Accessibility barriers, conflicts, and repairs: understanding the experience of professionals with disabilities in hybrid meetings’, in Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York: ACM, pp. 1–15

Angouri, J. and Marra, M. (2010) ‘Corporate meetings as genre: a study of the role of the chair in corporate meeting talk’, Text & Talk, 30(6), pp. 615–636. Available at: https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A8%3A30647064/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A57647024&crl=c&link_origin=scholar.google.com (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Ballakrishnen, S., Fielding-Singh, P. and Magliozzi, D. (2019) ‘Intentional invisibility: Professional women and the navigation of workplace constraints’, Sociological Perspectives, 62(1), pp. 23–4. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121418782185 (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Brescoll, V. L. (2011) ‘Who takes the floor and why: Gender, power, and volubility in organizations’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 56(4), pp. 622–641. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839212439994 (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Butler, D. and Geis F. L. (1990) ‘Nonverbal affect responses to male and female leaders: Implications for leadership evaluations’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(1), pp. 48–59. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.48 (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Dhawan, N. et al. (2021) ‘Videoconferencing Etiquette: Promoting Gender Equity During Virtual Meetings’, Journal of Women's Health, 30(4), pp. 460–465. Available at: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jwh.2020.8881 (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Howe, A. et al. (2023) ‘Gender and ethnicity intersect to reduce participation at a large European hybrid HIV conference’, BMJ Leader, 8, pp. 227–233. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/leader-2023-000848 (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Koch, S. C. (2005) ‘Evaluative affect display toward male and female leaders of task-oriented groups’, Small Group Research, 36(6), pp. 678–703. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247720413 (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Krivkovich, et al. (2024) Women in the workplace 2024: the 10th‑anniversary report. McKinsey & Company. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/women-in-the-workplace (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Mroz, J. E., Yoerger, M. and Allen, J. A. (2018) ‘Leadership in workplace meetings: The intersection of leadership styles and follower gender’, Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(3), pp. 309–322. (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2024) ‘The nature of violent crime in England and Wales: year ending March 2024’, 26 September. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/thenatureofviolentcrimeinenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2024 (Accessed: 28 July 2025).

Porter N., Geis F. L. and Jennings, J. (1983) ‘Are women invisible as leaders?’ Sex Roles, 9, pp. 1035–1049. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00289420 (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Rogerson-Revell, P. (2011) ‘Chairing international business meetings: Investigating humour and leadership style in the workplace’, in Constructing identities at work (pp. 61–84). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Sarkar, A. et al. (2021) ‘The promise and peril of parallel chat in video meetings for work’, in Extended abstracts of the 2021 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–8). Available at: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3411763.3451793 (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Standaert, W., Muylle, S. and Basu, A. (2022) ‘Business meetings in a postpandemic world: When and how to meet virtually’, Business Horizons, 65(3), pp. 267–275. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36062237/ (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

United Nations (UN) Global Compact (2025) Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. Available at: https://unglobalcompact.org/take-action/action/dei (Accessed: 26 June 2025).

Wang, S. S. and Roubidoux, M. A. (2020) ‘Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), videoconferencing, and gender’, Journal of the American College of Radiology, 17(7), pp. 918–920. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32479796/ (Accessed: 26 June 2025).