Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 21 February 2026, 11:52 AM

Unit 2 Being a participant – how to play nicely!

Introduction

Online meetings allow us to participate in different ways. Some participants may be highly involved, actively contributing and engaging in discussions with other attendees, while others might choose to keep a low profile and make minimal contributions. These are two sides of the same participation coin.

This unit is about how people participate, negotiate or withdraw in online meetings and how gender and power can play out in these situations. The aim of this unit is to reflect on how the many different ways people participate in these meetings can help create a fairer workplace. Creating an atmosphere where everyone feels comfortable to speak, respecting everyone’s turn and avoiding any signs of disrespect or aggression are essential to foster meaningful interactions.

Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes

By the end of this unit, you should be able to:

- Identify how gender and power influence the success of online work meetings.

- Assess the influence of different communication styles on building equitable online working relationships.

- Recognise different forms of microaggressions that might arise in an online meeting and familiarise yourself with the strategies you can use to resist them.

Welcome from the Unit 2 authors

Listen to the unit authors introducing themselves and sharing what they enjoyed most about the GEiO research project.

Note: In the audios below the authors speak in their first language. The transcript has been translated into English.

Next, go to 1 Gender and power relationships in online meetings.

1 Gender and power relationships in online meetings

In everyday life gender can affect work interactions. Research indicates that communication, power dynamics and participation are shaped by gender, as society assumes men and women will behave differently. Stereotypes about men and women are based on historical and cultural differences. Traditionally, men have been expected to go out to work, while women were expected to work in the home (the first being more public and the second more private). Men are expected to be providers, while women are seen as caregivers. Society is generally used to seeing men as competitive, task-oriented and logical, while women are viewed as nurturing, intuitive and relationship-focused.

According to research by Tannen (2006), in everyday talk men are expected to use direct and factual language, while women tend to use indirect and polite expressions. Men typically exhibit a ‘report talk’ style, prioritising content, status and direct problem solving. Women on the other hand, engage in ‘rapport talk’, focusing on building relationships, empathy and collaborative problem solving. People tend to believe that women are more skilled at interpreting non-verbal cues and maintaining eye contact, using gestures and facial expressions to convey emotions, whereas men tend to be more reserved in non-verbal communication, reflecting dominance and hierarchical tendencies.

In the workplace men and women are expected to handle conflicts and decision making differently, with men often internalising the process and women seeking collaborative input. Female managers are generally perceived as better communicators due to their openness and emotional connection.

Workplace interactions like videoconferencing reflect existing hierarchies, which can reinforce gender norms. For instance, women are often expected to take notes. However, while these structures can contribute to unequal relationships they can just as easily support equal ones. Online meetings can reproduce traditional power imbalances or offer opportunities to reshape these, where turn taking, interruptions and visibility play crucial roles. Addressing these processes is critical in fostering equitable participation and challenging structural inequalities in remote working environments.

However, it is essential to recognise that these patterns may vary. Understanding these differences and embracing new possibilities by fostering collaboration and adapting communication strategies can improve workplace harmony and productivity.

Now click on the headings in Figure 1 below to find short explanations for each communication category.

Now that you’ve had a chance to review communication categories, reflect further on your experiences in Activity 1 below.

Activity 1 Ensuring equal participation

Activity 1 Ensuring equal participation

2 Communication styles

How can different communication styles be effectively used to promote more equitable interactions in business videoconferencing?

Workplace communication has unique characteristics that set it apart from other types of social interactions. The language and dress code observed as well as the roles, actions and activities involved in this type of communication involve a set of norms that manifest themselves interactively. When this takes place through a screen it requires the display of additional skills by those in the meeting to ensure the smooth functioning and shared understanding among the attendees. In these cases, verbal and embodied behaviour becomes particularly significant and can lead to the expression of different communication styles.

A communication style can be defined as the linguistic and non-linguistic repertoire that a speaker brings into play when interacting with others (Mohindra and Azhar, 2012). Depending on their audience and position, the speaker can strategically adapt different skills to successfully meet the communicative demands of the situation. Additionally, as these styles are not inherently gender-based, they can be intentionally shaped and adjusted to promote gender equity in the workplace, helping to ensure that all voices in the organisation are heard.

There are (at least) four communication styles that can be identified and performed in professional meetings. The styles described below are not entirely discrete though; their features can be combined and varied based on the contexts and demands of interaction. What is crucial in practical terms is that the display of specific features can be detrimental to equitable interaction if:

- it causes certain voices or views to be silenced

- certain persons or positions are prevented from voicing their positions

- others are repeatedly interrupted, causing them to withdraw from participation.

The four most common communication styles that include both spoken and body language are shown below – click on each heading in Figure 2 to learn more.

Next, see if you can recognise these communication styles in Activity 2.

Activity 2 Recognising communication styles

Activity 2 Recognising communication styles

a.

Submissive

b.

Confrontational

c.

Assertive

d.

Cooperative

The correct answer is b.

b.

Your answer is correct. The use of foul language, an authoritarian tone and derogatory remarks towards others are typical of confrontational styles.

a.

Confrontational

b.

Submissive

c.

Cooperative

d.

Assertive

The correct answer is c.

c.

Your answer is correct. A cooperative style is often characterised by engaging in dialogue, acknowledging others’ views, contributions and needs, and seeking consensus.

a.

Confrontational

b.

Submissive

c.

Cooperative

d.

Assertive

The correct answers are b and d.

b.

This answer is correct. Isabel has some submissive ways of interacting; however, she also expresses opinions and ideas clearly, and respects others, so she mainly exemplifies an assertive style.

d.

This answer is correct. Expressing opinions and ideas clearly, while respecting others and asserting one’s own needs, exemplifies an assertive style. Nonetheless Isabel also shows some traits of the submissive communication approach.

3 Microaggressions

The European Commission has had specific regulations to address sexual violence and harassment since 2019. It recognises that this problem is directly related to gender bias. For this convention to be applied and respected, states and unions must collaborate. This can be seen in the following quote:

Violence and harassment at work is a widespread is a persistent phenomenon, with substantial adverse impacts for employees. This issue is entrenched in gender biases and stereotypes, and disproportionately affects women.

In September 2023, the Council adopted a position […] to ratify the Violence and Harassment Convention (ILO Convention 190)[35]. The 2019 Convention is the first international instrument setting out minimum standards on tackling work-related harassment and violence. Through effective cooperation with the International Labour Organization (ILO), the EU and its Member States played a crucial role in the adoption of the Convention.

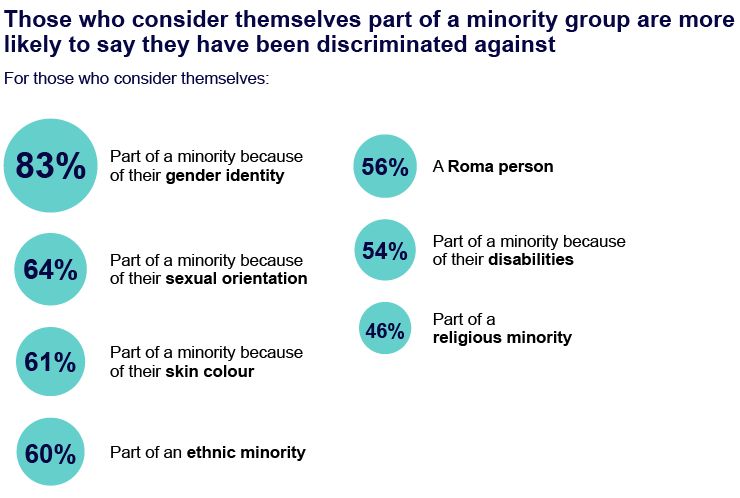

Violence and harassment at work are based on discrimination that can have multiple causes, among which are gender stereotypes and prejudices. The graph below illustrates the main reasons people report discrimination according to data from Eurostat (2022).

Note: The image below is an interactive ‘hover to reveal’ graph. Additional bar chart information for each discrimination group appears when you hover over the different coloured sections of each bar.

It's important to emphasise in this regard that discrimination is not just an interpersonal issue, but rather that organisational culture itself fosters the emergence of multiple instances of discrimination and violence. For example, workplace bullying is closely related to organisational culture and is expressed through various practices, many of which are verbal.

Workplace bullying is closely bound up with organizational culture, the social position of the target, and her or his role within the community. It can comprise a vast array of behaviour or tactics that can be explicit and visible or subtler and hidden, including public ridicule and humiliation, unfair treatment and criticism, emotional attacks, verbal and physical abuse, professional discrediting and devaluation, intimidation, withholding of information, and excessive monitoring.

In fact, many studies show that this is not an isolated phenomenon. For example, 73% of UK civil servants claim to have been bullied or harassed at least once (Cabinet Office, 2018).

The seriousness of the phenomenon led the United Nations to consider that this problem should be understood and addressed within the framework of respect for human rights, as it affects the worker's rights to health, safety and dignity which are recognised through the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The various international instruments designed in this regard serve as an umbrella for the development of specific national legislation that requires organisations to implement measures to protect this right.

In this context, the European Union recognises gender discrimination and sexual harassment in the workplace as particularly important problems and dictates that organisations are obligated to establish mechanisms for effectively addressing bullying and protecting those affected by it.

Sexual harassment at work is considered as a form of discrimination on the grounds of sex by Directives 2004/113/EC, 2006/54/EC and 2010/41/EU. Sexual harassment at work has significant negative consequences both for the victims and the employers. Internal or external counselling services should be provided to both victims and employers, where sexual harassment at work is specifically criminalised under national law. Such services should include information on ways to adequately address instances of sexual harassment at work and on remedies available to remove the offender from the workplace.

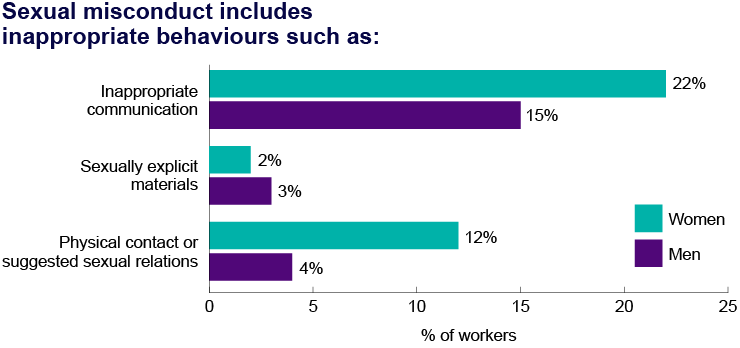

Sexually degrading attitudes and behaviours can be expressed in various ways at work and, as a Canadian study (Statistics Canada, 2021) illustrates, can affect one in four women and one in six men.

The severity of sexual harassment is also related to the fact that this problem tends to be persistent and widespread. As a statistic from the Australian Human Rights Commission (2018) shows, in more than half of cases the harassment lasts for more than six months, and 41% of those who experienced it were aware that other coworkers had experienced or were experiencing a similar situation.

This type of violence is taking on new nuances in work contexts mediated by new technologies. The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) asserts the seriousness of gendered hate speech in virtual environments, such as the use ICT to direct degrading and hateful language towards woman and girls and pointing out the victim’s gender (EIGE, 2022).

The general recommendation is to recognise cyberviolence against women and girls, adopt shared definitions to be able to identify and report it, and understand the continuum of violence between physical and virtual spaces.

This recognition, however, is even more difficult when the attacks occur in the form of microaggressions.

3.1 Microaggression in videoconferencing

The term ‘microaggressions’ was coined to identify every day and ‘normalised’, even if sometimes unintentional, expressions of racism – including verbal, behavioural or environmental indignities, slights and insults toward people of colour (Sue, Capodilupo and Torino, 2007).

It was later found that it could also be useful to identify:

Gender microaggressions as intentional or unintentional actions or behaviors that exclude, demean, insult, oppress, or otherwise express hostility or indifference toward women.

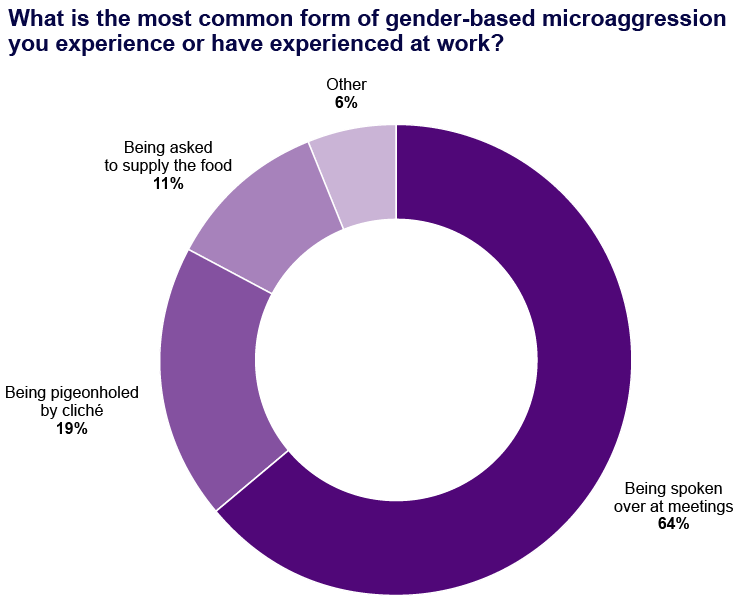

As the quote implies, this is a complex phenomenon that can take different forms as can be seen in this graph from the WomenTech Network (2025) – Figure 5.

In video conferencing spaces, this from of aggression can take on different forms, becoming more serious the more persistent or repeated they are over time. These include:

- Micro assault: for example, name-calling.

- Microinsults or ‘subtle snubs’.

- Microinvalidation of someone’s voice or knowledge.

- Abrupt interruption when someone is speaking.

- Patronising gendered communication like ‘mansplaining’ – this is a pejorative term used for when a man explains something, usually to a woman, in an overconfident, condescending manner, without regard to their expertise.

In Unit 1, Section 4, you were introduced to the Social Identity Wheel and the idea that different identities impact the ways you experience the world and how others might see and treat you. We all have many social identities that come together or intersect in ways that shape our experiences of privilege and discrimination. The idea that different social identities intersect is known as ‘intersectionality’. You will learn more about this idea in Unit 3.

How microaggressions are performed or experienced is shaped by different, intersecting social identities (e.g. gender, race, sexuality and so on). It is important to highlight that some people, namely those from minoritised groups, are not only targeted more often but are less likely to be given social support from their peers and are met with more negative consequences after enduring this type of assault (Biglia and Toledo, 2020).

Data from a survey carried out by an American company, Lean In (2024), shows how intersectionality is a key factor in the triggering of these microaggressions and that, contrary to what might be expected, there are several cases where these have increased from 2019 to 2024. The questioning of the expertise of women with disabilities and/or those belonging to the LGBTQI+ community, for example, is extremely high and shows an upward trend in the case of LGBTQI+ women.

3.2 The dimensions of the problem

Now work through the videos in Activity 3 to listen and reflect on the microaggression examples shown.

Activity 3 The dimensions of the problem

Activity 3 The dimensions of the problem

Watch the videos through without interruption.

Choose two and then watch them again, reflecting on what is happening by answering the questions that follow.

Note: If you are not familiar with the language being spoken, turn the subtitles on using the ‘CC’ button at the bottom right of the video player. You can also use the video transcript which is in English to help you make sense of the interactions.

4 Preparing to make a difference

In the preceding sections you covered gender and power relations, as well as the various communication styles and microaggressions present in the workplace. The following activity will allow you to reflect on the issues raised in the unit and your own ways of communicating.

Activity 4 Reflect on your own ways of communicating

Activity 4 Reflect on your own ways of communicating

Answer the questions in the table below and consider your experience in online meetings. Note that, along with the questions, some clues are included that may make it easier for you to reflect on your ways of communicating.

| Question | Some clues to answer | Reflection notes |

|---|---|---|

1. How do I talk to the other attendees? |

| |

2. How do I take and/or follow the lead? |

| |

3. Do I tend to interrupt the speaker frequently? |

| |

4. Do I get distracted and take the opportunity to engage in other activities or carry out internet research while the meeting is in progress? |

| |

5. How do I deal with a possible argument? |

|

Now you've reflected on your own ways of communicating in meetings, in the next section you will focus on how to respond to other peoples’ behaviour.

4.1 Responding to microaggressions

In Activity 5 you will build your toolkit resource for note taking and responding to microaggressions.

Activity 5 Building your toolkit

Activity 5 Building your toolkit

Here you can create your own resource sheet with relevant details on microaggressions, with space to develop the toolkit and add further information and notes on instances of microaggressions. If you find it useful you can share the resource with your colleagues.

Start by opening a note taking or word processing application like Microsoft Word and make notes based on the details in a–g below.

a. The EU Directive on combating violence against women and domestic violence (7 May 2024), including measures to prevent and protect against gender violence and harassment at work, has to be transposed by the member states into their domestic legislation and policy before 14 June 2027.

Check if they have done it in your country or what legislation is in use and save the reference

b. By law, companies are responsible for sexism and microaggressions. They should have a department in place to prevent and report it, as well as a protocol for intervention. If there is an organisational norm or protocol for dealing with microaggressions, read it and note the relevant data in your resource sheet in particular:

- Where this document can be found.

- Which department is in charge of intervening.

- What behaviours are included as microaggressions in the protocol.

- How can you contact the specific department or the person in charge (telephone number, email, app etc.)

c. Determine whether your company has a psychological support service in place, how it can be accessed, and/or who is responsible for health support services.

d. Look for materials that can help you better understand what constitutes a microaggression and why it is essential to address this issue or raise awareness among your colleagues – some examples are:

- How microaggressions are like mosquito bites – Fusion Comedy (2016)

- How I deal with microaggressions at work – BBC video (2024)

- Gender related Microaggressions – Royal Pharmaceutical Society Posters (n.d.)

e. If you experience a microaggression during a videoconference:

- Write down some sentences you can use to interrupt it or prevent it from going further. Options could include directly addressing the person responsible (only in situations that make you feel safe), responding with irony or humour (see Unit 4) to the aggression, communicating that you are feeling uncomfortable, taking time to relax, turning off your camera, or providing a plausible justification to leave the meeting.

- If you anticipate that someone might be aggressive towards you in a meeting, you can prepare some strategies with colleagues that can help to interrupt or reduce the effect of the microaggression. Identify which colleagues could be helpful and how their position and communication skills might help to develop a strategy; if the potential aggressor is not the chair or line manager, consider if you would feel comfortable speaking to your line manager or chair to prevent the situation.

- Think about a trusted person you could speak with afterwards for support.

- Identify some managers you may want to inform about the situation and ask them to support you in any action you decide to take.

f. If you witness a microaggression during an online meeting (remembering that you should always respect the person affected):

- Consider ways of interrupting the microaggression (e.g. validating the person targeted or what they have said, pointing out that what has been said is inappropriate; invalidating the aggressive discourses, not the person who has produced them, indicating your support to the person who has been targeted, with a private message or with a gesture).

- You may want to speak privately to the person who has been aggressive to make them aware of what has occurred and your discomfort with it (take some notes that can help you to communicate this).

- Ask the person targeted how they feel and what kind of support and help you might offer (take some notes that will help you to communicate this, and you may also want to share your resource sheet).

g. Identify services in your community that can provide support to persons who have suffered (micro)aggression:

- Women's support services.

- Hate prevention groups.

- LGBTQI+ support centres.

- Labour unions.

- Employment law firms.

Links to support services

Unit 2 conclusion

Throughout this unit you’ve explored how gender and power dynamics shape participation in online meetings and learned to recognise different communication styles and their impact on team equity. You also examined how microaggressions can emerge in workplace videoconferences, as well as looked at strategies to resist them.

Now is the time to reflect on what you’ve learned and consider how these insights may be relevant to your own virtual interactions. Think about how you can help foster a respectful, equitable, and effective online working environment by taking a few minutes to test your learning in the Unit 2 practice quiz.

Unit 2 practice quiz

Now have a go at the Unit 2 practice quiz – you can attempt the quiz as many times as you like.

After you have completed the Unit 2 quiz move onto Unit 3 Leading the way – effective chairing.

References

Australian Human Rights Commission (2018) National survey. Available at: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-01/Stats%20workplace%20sexual%20harassment_infographic.pdf (Accessed: 21 July 2025).

Basford, T.E., Offermann, L.R. and Behrend, T.S. (2013) ‘Do you see what I see? Perceptions of gender microaggressions in the workplace’, Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(3), pp. 340–349. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313511420 (Accessed: 21 July 2025).

BBC (2024) How I deal with microaggressions at work [Video]. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/videos/cek91zpzp7ro (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

Biglia, B. and Toledo, P. (2020) ‘Workplace bullying’, in The SAGE encyclopedia of higher education. Vol. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 1684–1685. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529714395 (Accessed: 21 July 2025).

Cabinet Office (2018) Bullying, harassment and misconduct survey. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b9fc10ce5274a55c816f6e1/2018-07-20_Sue_Owen_Review_-_Annex_Survey.pdf (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

European Commission (2024) 2024 report on gender equality in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/965ed6c9-3983-4299-8581-046bf0735702_en?filename=2024%20Report%20on%20Gender%20Equality%20in%20the%20EU_coming%20soon.pdf (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) (2022) Combating cyber violence against women and girls. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available at: https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/publications/combating-cyber-violence-against-women-and-girls (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

European Union (2024) Directive (EU) 2024/1385 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 May 2024 on combating violence against women and domestic violence. Official Journal of the European Union, L 1385. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401385 (Accessed: 1 December 2025).

Eurostat (2022) Self-perceived discrimination at work – statistics. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Self-perceived_discrimination_at_work_-_statistics (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

Fusion Comedy (2016) Microaggressions are like mosquito bites [Video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDd3bzA7450 (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

International Labour Organization (ILO) (2019) Violence and Harassment Convention, 2019 (No. 190). Available at: https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C190 (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

Lean In (2024) Women in the workplace – the 10th anniversary report. McKinsey & Company. Available at: https://cdn-static.leanin.org/women-in-the-workplace/2024-pdf (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

Mohindra, V. and Azhar, S. (2012) ‘Gender communication: a comparative analysis of communicational approaches of men and women at workplaces’, Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(1), pp. 18–27. Available at: https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-0211827 (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

Royal Pharmaceutical Society (n.d.) Royal Pharmaceutical Society posters: how to recognise gender related microaggressions, and what do gender related microaggressions look like? Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/recognition/inclusion-diversity/microaggressions/gender (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

Statistics Canada (2021) Sexual misconduct and gender-based discrimination at work, 2020. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/11-627-M2021061 (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

Sue, D.W., Capodilupo, C.M. and Torino, G.C. (2007) ‘Microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice’, American Psychologist, 62(4), pp. 271–286. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. (Accessed: 24 July 2025).

Tannen, D. (2006) ‘Put down that paper and talk to me: rapport-talk and report-talk’, in Monaghan, L. and Goodman, J.E. (eds) A cultural approach to interpersonal communication: essential readings. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 179–194.