Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 23 February 2026, 2:35 PM

Integrated Management of newborn and Childhood Illness Module: 2. Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

Study Session 2. Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

Introduction

Health statistics show that world wide about 4 million newborn babies die each year; another 4 million babies each year are stillborn; most die in late pregnancy or labour and most newborn deaths occur in developing countries. The same statistics show that about two-thirds of deaths in the first year of life occur in the first month of life; of those who die in the first month, about two-thirds die in the first week of life and of those who die in the first week, two-thirds die in the first 24 hours of life. Eighty-five percent of newborn deaths are due to three main causes: infection, birth asphyxia, and complications of prematurity and low birth weight (LBW).

In addition to the direct causes of death, many newborns die because of their mother’s poor health (see Box 2.1), or because of lack of access to essential care. Sometimes the family may live hours away from a referral facility or there may not be a skilled health worker in their community. The newborn child is extremely vulnerable unless he or she receives appropriate basic care, also called essential newborn care. When newborns don’t receive this essential care, they quickly fall sick and too often they die. For premature or LBW babies, the danger is even greater.

Box 2.1 Newborn care starts before birth

As a Health Extension Practitioner you need knowledge and skills to give essential newborn care and to recognise and manage common newborn problems. It is also essential for you to understand that good newborn health depends on good maternal health and nutrition, especially during pregnancy, labour and postpartum, and you are well placed to help families adopt healthy practices.

In the Antenatal Care, Labour and Delivery Care and Postnatal Care Modules you have learned about focused antenatal care, the skills you need to provide safe and clean delivery and the content and timing of postnatal care. We believe that you have gained understanding that care for the newborn and care for the mother are always integrated and that it is important for you to know how to provide effective health services in a holistic way that takes into account the needs of both the mother and her newborn.

In this study session you are going to learn about the knowledge and skills you need to provide essential newborn care and your role in supporting the mother and her new baby. You have already covered some of the issues in the Postnatal Care Module; however newborn care is such a crucial part of your work as a Health Extension Practitioner that it is useful for you to revisit some of the key points, as well as learn new information that will help you carry out your role as effectively as possible.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 2

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

2.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3)

2.2 Describe how to give essential newborn care. (SAQs 2.1 and 2.2)

2.3 Explain how to assess, classify and treat a young infant for birth asphyxia. (SAQs 2.1 and 2.2)

2.4 Explain how to assess and classify and treat low birth weight babies. (SAQs 2.2 and 2.3)

2.5 Describe how to provide postnatal follow-up care. (SAQ 2.3)

2.1 Essential newborn care

The majority of babies are born healthy and at term. The care they receive during the first hours, days and weeks of life can determine whether they remain healthy. All babies need basic care to support their survival and wellbeing. This basic care is called essential newborn care (ENC) and it includes immediate care at birth, care during the first day and up to 28 days.

Most babies breathe and cry at birth with no help. Remember that the baby has just come from the mother’s uterus, an environment that was warm and quiet and where the amniotic fluid and walls of the uterus gently touched the baby. You too should be gentle with the baby and keep the baby warm. Skin-to-skin contact with the mother keeps her baby at the perfect temperature, so you should encourage and help the mother to keep the newborn baby warm in this way.

The care you give the baby and mother immediately after birth is simple but important. In this study session you will learn about the steps of immediate care which should be given to all babies at birth. You will look at how to assess, classify and treat newborns for birth asphyxia and low birth weight as well as how to monitor the mother’s condition closely in the minutes and hours after the birth.

2.2 The eight steps of essential newborn care

Before you look at the eight steps of essential newborn care (ENC) you need to remember the importance of the ‘three cleans’ that you learned in Study Session 3 of the Labour and Delivery Care Module. These are clean hands, clean surface and clean equipment. Your equipment should include two clean dry towels, cord clamps, razor blade, cord tie, functional resuscitation equipment, vitamin K, syringe and needles, and tetracycline eye ointment.

Step 1 Deliver the baby onto the mother’s abdomen or a dry warm surface close to the mother.

Continue to support and reassure the mother. Tell her the sex of the baby and congratulate her.

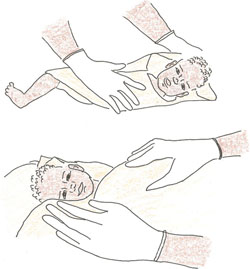

Step 2 Dry the baby’s body with a dry warm towel as you try to stimulate breathing. Wrap the baby with another dry warm cloth and cover the head (Figure 2.1).

Dry the baby well, including the head, immediately and then discard the wet cloth. Wipe the baby’s eyes. Rub up and down the baby’s back, using a clean, warm cloth. Drying often provides sufficient stimulation for breathing to start in mildly depressed newborn babies. Do your best not to remove the vernix (the creamy, white substance which may be on the skin) as it protects the skin and may help prevent infection. Then wrap the baby with another dry cloth and cover the head.

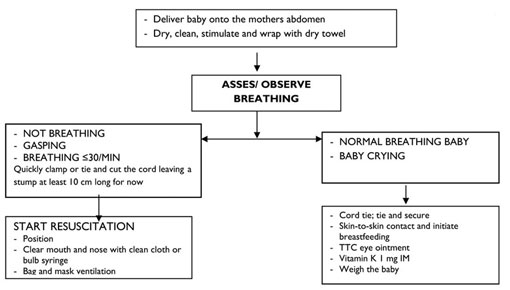

Step 3 Assess breathing and colour; if not breathing, gasping or there are less than 30 breaths per minute, then resuscitate.

You will remember that you learned how to manage a newborn baby with birth asphyxia in Study Session 7 of the Labour and Delivery Care Module.

As you dry the baby, assess its breathing. If a baby is breathing normally, both sides of the chest will rise and fall equally at around 30–60 times per minute. Thus, check if the baby is:

- Breathing normally

- Having trouble breathing

- Breathing less than 30 breaths per minute, or

- Not breathing at all.

![]() Resuscitation of a baby who is not breathing must start within one minute of birth.

Resuscitation of a baby who is not breathing must start within one minute of birth.

If the baby needs resuscitation, quickly clamp or tie and cut the cord, leaving a stump at least 10 cm long for now and then start resuscitation immediately. Functional resuscitation equipment should always be ready and close to the delivery area since you must start resuscitation within one minute of birth. It may sound as if you have a lot to do in one minute, but the steps described here are ones that you can take simultaneously. That is, while you are delivering the baby onto the mother’s abdomen and drying the baby, you can assess breathing and colour and take urgent action if necessary.

Step 4 Tie the cord two fingers’ length from the baby’s abdomen and make another tie two fingers from the first one (Figure 2.2). Cut the cord between the first and second tie. If the baby needs resuscitation, cut the cord immediately. If not, wait for 7–3 minutes before cutting the cord.

- Tie the cord securely in two places:

- Tie the first one two fingers away from the baby’s abdomen.

- Tie the second one four fingers away from the baby’s abdomen.

- Make sure that tie is well secured; the thread you use to tie the cord must be clean.

- Cut the cord between the ties:

- Use a new razor blade, or a boiled one if it has been used before, or sterile scissors.

- Use a small piece of cloth or gauze to cover the part of the cord you are cutting so no blood splashes on you or on others.

- Be careful not to cut or injure the baby. Either cut away from the baby or place your hand between the cutting instrument and the baby.

- Do not put anything on the cord stump.

Step 5 Place the baby in skin-to-skin contact with the mother, cover with a warm cloth and initiate breastfeeding.

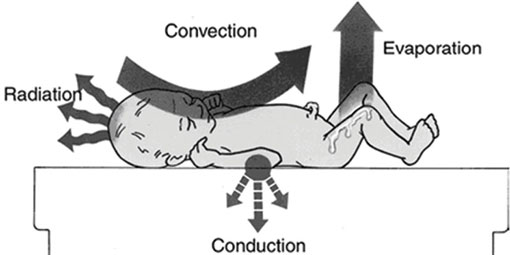

The newborn loses heat in four ways (see Figure 2.3 below):

- Evaporation: when amniotic fluid evaporates from the skin.

- Conduction: when the baby is placed naked on a cooler surface, such as the floor, table, weighing scales, cold bed.

- Convection: when the baby is exposed to cool surrounding air or to a draught from open doors and windows or a fan.

- Radiation: when the baby is near cool objects, walls, tables, cabinets, without actually being in contact with them.

The warmth of the mother passes easily to the baby and helps stabilise the baby’s temperature.

- Put the baby on the mother’s chest, between the breasts, for skin-to-skin warmth.

- Cover both mother and baby together with a warm cloth or blanket.

- Cover the baby’s head.

The first skin-to-skin contact should last uninterrupted for at least one hour after birth or until after the first breastfeed. The baby should not be bathed at birth because a bath can cool the baby dangerously. After 24 hours, the baby can have the first sponge bath, if the temperature is stabilised.

If everything is normal, the mother should immediately start breastfeeding.

For optimal breastfeeding you should do the following:

- Help the mother begin breastfeeding within the first hour of birth (Figure 2.4).

- Help the mother at the first feed. Make sure the baby has a good position, attachment, and is sucking well. Do not limit the length of time the baby feeds; early and unlimited breastfeeding gives the newborn energy to stay warm, nutrition to grow, and antibodies to fight infection.

The steps to keep the newborn warm are called the warm chain.

- Warm the delivery room.

- Immediate drying.

- Skin-to-skin contact at birth.

- Breastfeeding.

- Bathing and weighing postponed.

- Appropriate clothing/bedding.

- Mother and baby together.

- Warm transportation for a baby that needs referral.

Step 6 Give eye care (while the baby is held by its mother).

Shortly after breastfeeding and within one hour of being born, give the newborn eye care with an antimicrobial medication. Eye care protects the baby from serious eye infection which can result in blindness or even death.

The steps for giving the baby eye care are these:

First, wash your hands, and then using tetracycline 1% eye ointment:

- Hold one eye open and apply a rice grain size of ointment along the inside of the lower eyelid. Make sure not to let the medicine dropper or tube touch the baby’s eye or anything else (see Figure 2.5).

- Repeat this step to put medication into the other eye.

- Do not rinse out the eye medication.

- Wash your hands again.

Step 7 Give the baby vitamin K, 1 mg by intramuscular injection (IM) on the outside of the upper thigh (while the baby is held by its mother).

After following correct infection prevention steps, with the other hand stretch the skin on either side of the injection site and place the needle straight into the outside of the baby’s upper thigh (perpendicular to the skin). Then press the plunger to inject the medicine. You will be learning more about safe injection techniques in your practical skills training sessions. There is also a study session on routes of injection in the Immunization Module.

Step 8 Weigh the baby.

Weigh the baby an hour after birth or after the first breastfeed. If the baby weighs less than 1,500 gm you must refer the mother and baby urgently.

![]() Newborn babies who weigh less than 1,500 gm must be referred urgently to a hospital.

Newborn babies who weigh less than 1,500 gm must be referred urgently to a hospital.

Why do you need to give essential newborn care?

At birth the newborn must adapt quickly to life outside the uterus. As a trained Health Extension Practitioner, you can take steps to ensure the baby is breathing well, kept warm and receives breastmilk from the mother.

2.3 Newborn danger signs

Although many babies will have a healthy birth and will breathe easily and begin feeding soon after being placed on the mother’s breast, other babies will have a range of needs, some urgent, in order to ensure their safety and wellbeing.

It is very important that you check the newborn for the danger signs listed in Box 2.2, as the actions you take to help the newborn are crucial to ensure prompt and safe care. You also need to teach the mother to look for these signs in the newborn and advise her to seek care promptly if she observes any one of the danger signs.

The axillary temperature is measured with a thermometer in the baby’s armpit.

Box 2.2 Newborn danger signs

Newborn danger signs; refer baby urgently if any of these is present:

- Breathing less than or equal to 30 or more than or equal to 60 breaths per minute, grunting, severe chest indrawing, blue tongue and lips, or gasping.

- Unable to suck or sucking poorly.

- Feels cold to touch or axillary temperature less than 35°C.

- Feels hot to touch or axillary temperature equal to or greater than 37.5°C.

- Red swollen eyelids and pus discharge from the eyes.

- Convulsion/fits/seizures.

- Jaundice/yellow skin (at age less than 24 hours or more than two weeks) involving soles of the feet and palms of the hands.

- Pallor.

- Bleeding.

- Repeated vomiting, swollen abdomen, no stool after 24 hours.

2.4 Birth asphyxia

As a Health Extension Practitioner you might be the only person present able to help the baby start breathing and prevent complications caused through lack of oxygen to the brain in the first few minutes after delivery. You therefore have an important role in the early moments and hours after birth. After completing this section you will understand the causes of birth asphyxia and be able to assess, classify and manage a newborn baby for birth asphyxia.

You may recall that you first learned about birth asphyxia in Study Session 7 of the Labour and Delivery Care Module. You should remember that birth asphyxia is when the baby receives too little oxygen because it does not begin or sustain adequate breathing at birth. Birth asphyxia can occur for many reasons. For example:

During pregnancy the mother may have:

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Diabetes

- Infection

- Asthma.

During delivery complications may include:

- Preterm labour

- Prolonged or obstructed labour

- Cord coming down in front of the baby (prolapsed cord)

- Placenta covering, or partially covering, the cervix instead of being near the top of the uterus where it should be (placenta praevia)

- Detached placenta (placental abruption).

There are also other factors such as the baby being born preterm or post-term, the mother having had multiple gestations, or cord or placenta problems which prevent blood flow to the baby.

If you need to remind yourself about these problems, you should go back to Study Sessions 17–21 in the Antenatal Care Module, and Study Sessions 7–11 in the Labour and Delivery Care Module.

2.4.1 Assess and classify birth asphyxia

If you are attending a delivery or a baby is brought to you immediately after birth, you should assess for birth asphyxia. Assess the baby after drying and wrapping him or her with a dry cloth. To assess for birth asphyxia, you need to look and listen for breathing patterns.

Assess asphyxia

- No breathing: the newborn has not cried or there are no spontaneous movements of the chest.

- Gasping: the newborn attempts to make some effort to breathe with irregular and slow breathing movements.

- Breathing poorly: count breaths in one minute. The normal breathing rate of a newborn baby is 30‒60 per minute. If the breathing rate is less than 30 per minute it is a sign of asphyxia.

Classify asphyxia

There are two possible classifications:

- Birth asphyxia

- No birth asphyxia.

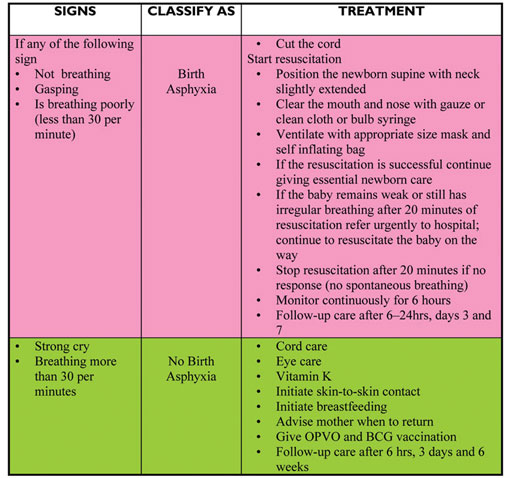

It is critical that you treat birth asphyxia quickly; if you don’t, the baby may die or may develop complications from which he or she never fully recovers. Table 2.1 sets out a summary of the signs of asphyxia and the treatment that should be given.

Table 2.1 Assessment, classification and management of birth asphyxia.

If you need to remind yourself about the detail of how to manage birth asphyxia you should revisit Study Session 7 of the Labour and Delivery Care Module.

If there is no birth asphyxia and the baby is crying strongly or breathing more than 30 breaths per minute you should continue with essential newborn care, as summarised in Figure 2.6.

2.5 Assess, classify and manage low birth weight babies

In this section you will learn about problems associated with prematurity (preterm, born before 37 weeks of pregnancy) and low birth weight (LBW) (a small for gestational age baby who did not grow well enough in the uterus during pregnancy) and how to manage these. This is important because LBW babies are more likely to have breathing and feeding problems and develop infection and die than babies with a birth weight of 2,500 gm or more. LBW babies who survive are likely to have more medical and developmental problems than normal term babies. Most communities believe that these babies are born to die. As a Health Extension Practitioner you have an important role to change this belief and help mothers and family members to provide the extra care the LBW baby needs. Box 2.3 sets out some of the common problems for premature or LBW babies.

What is low birth weight? What is very low birth weight?

You learned the definition of LBW and very LBW in Study Session 8 of the Postnatal Care Module.

Low birth weight is where a baby weighs less than 2,500 gm at birth. A very low birth weight baby is one who weighs less than 1,500 gm at birth. A LBW baby can be premature, or small for gestational age.

Box 2.3 Low birth weight babies: problems and explanations

| Problems | Explanations |

|---|---|

| Breathing problems: | - Immature lungs - Hypothermia (baby too cold) - Infections |

| Low body temperature: | - Immature body temperature regulating system - Low body fat |

| Low blood sugar: | - Low energy store |

| Feeding problem: | - Inability to suck or coordinate breathing and swallowing - Small size - Low energy - Small stomach |

| Infections: | - Not well developed immune system |

| Jaundice: | - Not well developed liver to break down bilirubin (the substance found in blood that gives it red colour and helps in oxygen transport) |

| Bleeding problem: | - Not well developed clotting mechanisms. |

2.5.1 Characteristics of premature babies

Premature babies have a number of characteristics depending on their gestational age:

- Skin: may be reddened. The skin may be thin so blood vessels are easily seen.

- Lanugo: there is a lot of fine hair all over the baby’s body.

- Limbs: the limbs are thin and may be poorly flexed or floppy due to poor muscle tone.

- Head size: appears large in proportion to the body. The fontanelles (open spaces where skull bones join) are smooth and flat.

- Chest: no breast tissue before 34 weeks of pregnancy.

- Sucking ability: weak or absent.

- Genitals: in boys the testes may not be descended and the scrotum may be small; in girls the clitoris and labia minora may be large.

- Soles of feet: creases are located only in the anterior (front) of the sole, not all over, as in the term baby.

2.5.2 Assess birth weight and gestational age

If you are attending delivery or a baby is brought to you within seven days of birth, you must assess for birth weight and gestational age. You can do this in the following way:

Assess

You should ask the mother about the gestational age; that is, the duration of the pregnancy in weeks when the baby was born. Use the mother’s word or recollection of the time of her last normal menstrual period (LNMP) if she can remember this, to estimate gestational age. If this is not possible you should use the baby’s weight to do the classification.

Then weigh the baby; if you do not have the birth weight (weight taken within 24 hrs of birth), the weight taken in the first seven days of life may be used for the classification of birth weight.

Classify

There are three possible classifications:

- Very low birth weight and/or very preterm

- Low birth weight and/or preterm

- Normal weight and/or term.

2.5.3 Treatment for low birth weight babies

The death rate for LBW babies is very high. With simple care you can support and advise the family how to care for a LBW baby and improve greatly their chances of survival.

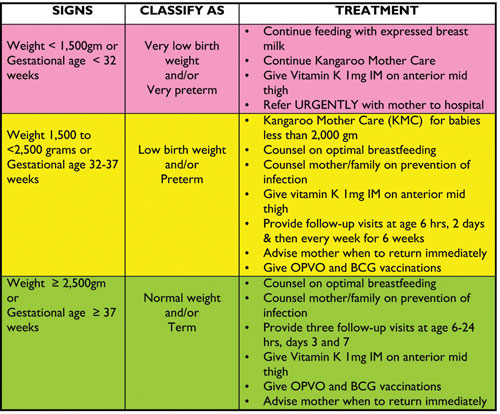

Table 2.2 describes the treatment that you should give a LBW baby and the advice that you should give the baby’s mother.

Table 2.2 Assessment, classification and treatment of low birth weight babies.

2.5.4 Kangaroo mother care (KMC)

Kangaroo mother care has three main components. KMC is also covered in Study Session 8 of the Postnatal Care Module; however as it is such an important aspect of newborn care we have also included it in this study session. You will also learn more about KMC in your practical skills sessions.

1 Continuous skin-to-skin contact between the baby’s front and the mother’s chest: skin-to-skin contact starts at birth and is continued day and night. There may be brief interruptions such as when the baby is being bathed. The baby wears only a hat or cloth, to keep its head warm, and a nappy/diaper (see Figure 2.7).

2 Exclusive breastfeeding: the baby breastfeeds within one hour after birth and then every two to three hours (see Figure 2.8). The baby is unlikely to be able to suck the breast properly so you will need to support the mother to express milk so that she can also cup feed her baby.

3 Support to the mother: the mother can continue to do what she normally does while providing KMC, for example cook, clean and sleep. However she needs support from you as the health worker, as well as her family and others in the community; by keeping the baby skin-to-skin for short periods while the mother rests or takes care of other duties.

How does KMC help the baby and the mother?

KMC helps the baby in stabilising its temperature, making the breathing stable and regular, improving immunity, reducing infection and enabling it to feed better and gain weight faster. KMC helps the mother in becoming more attached to her baby emotionally; gives her confidence and ability to care for her small baby.

2.6 Newborn postnatal follow-up home visits

The postnatal period (the first six weeks after birth) is critical to the health and survival of a mother and her newborn. Sixty percent of maternal and 75% of newborn deaths occur during the first postpartum week. Lack of care in this period may result in death or disability as well as missed opportunities to promote healthy behaviour, affecting women, newborns and children. As around 94% of the mothers in your community deliver at home, it is important to provide three home visits for postnatal care for normal weight babies at the critical times and arrange for the mother to come to the health post at six weeks for the fourth visit. You will need to make one extra home visit for low birth weight babies.

During these visits your role as a Health Extension Practitioner is to undertake a range of tasks aimed at ensuring the health of the baby and mother, and to do what you can to support the mother’s care of her new baby. The following section outlines your main tasks during the first six weeks after the baby’s birth. You have learned this in more detail in the Postnatal Care Module.

2.6.1 Six to 24 hours’ visit and evaluation

- Check for danger signs in the newborn and in the mother

- Counsel the mother/family to keep the newborn warm

- Counsel the mother/family on optimal breastfeeding

- Check the baby’s umbilicus for bleeding

- Counsel the mother to keep umbilicus clean and dry and take infection prevention precautions

- Weigh the newborn, if not weighed at birth

- Immunize the newborn with oral polio vaccine (OPV) and BCG vaccine to protect against tuberculosis

- Give the newborn vitamin K, 1 mg (IM) if it has not been given before

- Give one capsule of 200,000 IU (International Units) vitamin A to the mother

- Counsel the lactating mother to take at least two more meals than usual every day.

Vaccination with OPV and BCG is taught in the Immunization Module.

2.6.2 Two days’ visit to low birth weight/preterm, low body temperature babies

- Check for danger signs in the newborn

- Counsel and support optimal breastfeeding

- Follow-up of kangaroo mother care

- Follow-up of counselling to the mother given during previous visits

- Counsel mother/family to protect the newborn from infection

- Give one capsule of 200,000 IU vitamin A to the mother if not given before

- Immunize the newborn with OPV and BCG if not given before now.

2.6.3 Three days’ visit

- Check for danger signs in the newborn

- Counsel and support optimal breastfeeding

- Follow-up of kangaroo mother care

- Follow-up of counselling given during previous visits

- Counsel mother/family to protect the newborn from infection

- Give one capsule of 200,000 IU vitamin A to the mother if not given before

- Immunize the newborn with OPV and BCG if not given before

- Counsel mother/father on healthy birth spacing, on return of fertility and postpartum family planning.

2.6.4 Seven days’ visit

- Check for danger signs in the newborn

- Counsel and support optimal breastfeeding

- Counsel mother/father on healthy birth spacing, on return of fertility and postpartum family planning

- Follow-up of kangaroo mother care

- Follow-up of counselling given during previous visits

- Counsel mother/family to protect the newborn from infection

- Give one capsule of 200,000 IU vitamin A to the mother if not given before

- Immunize the newborn with OPV and BCG if not given before.

You have now covered the immediate newborn care that you will need to provide in your role as the Health Extension Practitioner. You have also seen how timing and home visits are crucial for both the immediate care and postnatal care. Your support for and advice to the mother and family of the newborn is very important and can make a big difference to the health of the mother and her new baby.

Summary of Study Session 2

In Study Session 2, you have learned that:

- The majority of newborn deaths occur during the first week and first 24 hours.

- Birth asphyxia and prematurity/low birth weight are two of the three major causes of newborn deaths (infections are the third cause and you will learn more about these in the next study session).

- Basic care of the newborn is called essential newborn care and it includes immediate care at birth, care during the first day, and up to 28 days.

- Birth asphyxia is when a baby does not begin or sustain adequate breathing at birth. There are a number of causes of birth asphyxia including prolonged labour, the cord or placenta problems, and premature birth.

- If the newborn is not breathing, or is gasping, or is breathing poorly (less than 30 breaths per minute) you should classify as birth asphyxia and start resuscitation immediately. The first minutes are crucial moments to prevent brain damage.

- LBW refers to a newborn who weighs less than 2,500 gm at birth and a very low birth weight baby is one who weighs less than 1,500 gm at birth. A LBW baby can be premature or small for gestational age. These babies need special care in order to have a better chance to live and be healthy.

- Kangaroo mother care is a simple and safe way that mother and family can provide to help the low birth weight baby adjust to life outside the uterus. The three main components are continuous skin-to-skin contact, exclusive breastfeeding and family support to the mother.

- It is important to check the newborn at every visit for general danger signs such as difficult breathing, low or high body temperature, difficulties in feeding and a range of possible infections.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 2

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the questions below. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

Read Case Study 2.1 and answer the question below.

Case Study 2.1

You are called to Workitu’s home because the delivery is delayed. You help Workitu and she delivers a baby girl. The baby is breathing less than 30 breaths per minute.

SAQ 2.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3)

What do you do?

Answer

You need to start resuscitation immediately. Clear the baby’s mouth and nose and position her correctly. Then start bag and mask ventilation.

SAQ 2.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 2.1, 2.2, 2.3 and 2.4)

What do you think is the best kind of care for a low birth weight baby? Explain your answer.

Answer

Kangaroo mother care is best because it means the baby is always in contact with the mother and feeds frequently so it will grow stronger. It also means the mother is able to carry on with her usual life as much as possible.

SAQ 2.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 2.1, 2.3 and 2.5)

Why is it so important to visit the mother and baby at home during the six weeks after the baby’s birth?

Answer

These visits are important because lack of care just after the baby is born can result in death or disability. So danger signs need checking for. You also need to counsel and give advice to the mother on how to look after the child. The baby will also need immunizations, and mother and baby will need vitamin A.