Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 3 December 2025, 2:06 AM

Integrated Management of newborn and Childhood Illness Module: 3. Management of Bacterial Infection and Jaundice in the Newborn and Young Infants

Study Session 3. Management of Bacterial Infection and Jaundice in the Newborn and Young Infants

Introduction

As a Health Extension Practitioner you will encounter young infants who need your care. Young infants’ illness forms a major part of health problems for children under five years old in Ethiopia, and your skills in being able to assess, classify and treat young infants is a crucial aspect of your role. In this study session you will learn how to manage a sick young infant from birth up to two months old.

Young infants have special characteristics that must be considered when classifying their illness. They can become sick and die very quickly from serious bacterial infections. They frequently have only general signs, such as few movements, fever, or low body temperature. This study session will teach you how to assess, classify and treat a young infant. In particular, it focuses on how to assess and classify bacterial infection and jaundice in a young infant, when you need to refer a young infant for other urgent medical services and, as a Health Extension Practitioner, what pre-referral treatment (one dose of treatment) you can provide just before sending a young infant to a referral facility.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 3

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

3.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 3.1 and 3.2)

3.2 Assess and classify a young infant for possible bacterial infection and jaundice. (SAQs 3.1and 3.2)

3.3 Determine if urgent referral of the young infant to hospital for medical treatment is needed. (SAQ 3.2)

3.4 Identify what pre-referral treatments are needed for young infants who need urgent referral. (SAQ 3.2)

3.5 Write a referral note. (SAQ 3.2)

3.6 Identify the range of treatment for young infants with local bacterial infection or jaundice who can be looked after at home. (SAQ 3.1)

3.7 Provide follow-up care for the young infant. (SAQ 3.1)

3.1 Assess and classify the young infant

Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs. Sepsis occurs when infection spreads to the bloodstream. Meningitis is an infection of the thin tissues that cover the brain and spinal cord.

A young infant can become sick and die very quickly from serious bacterial infections such as pneumonia, sepsis and meningitis. Therefore if a young infant is brought to you because they are, or appear to be, sick it is important that you assess the infant carefully.

3.1.1 Gaining the mother’s trust

When you see the mother and her sick child you should begin by greeting the mother appropriately and ask her to sit with her child. You should ask the mother if this is the first visit or a follow-up visit (unless you know this already) and ask her what the young infant’s problems are. You need to know her child's age so you can choose the right case management chart (which you will come to later in this study session). As you may recall from Study Session 1, children from birth up to two months will be assessed and classified by you according to the steps on the young infant chart.

You do not need to weigh the young infant or measure their temperature until later in the visit when you assess and classify the young infant’s main symptoms. At the early stage in the visit, you do not need to undress or disturb the baby.

3.1.2 Good communication skills

An important reason for asking the mother a few simple questions at the beginning of the visit is to open good communication with her. This will help to reassure the mother that her baby will receive good care. When you treat the infant’s illness later in the visit or during any follow-up visits, you will need to teach and advise the mother about caring for her sick infant at home. You will learn more about how to communicate with and counsel the mother effectively about home treatment in Study Session 14 in this Module. The key point is that it is important to establish good communication with the mother from the beginning of the visit.

Good communication involves using several skills. You should:

- Listen carefully to what the mother tells you. This will show her that you are taking her concerns seriously.

- Use words the mother understands. If she does not understand the questions you ask her, she cannot give the information you need to assess and classify the infant correctly.

- Give the mother time to answer the questions. For example, she may need time to decide if the sign you asked about is present.

- Ask additional questions when the mother is not sure about her answer. When you ask about a main symptom or related sign, the mother may not be sure if it is present. Ask her additional questions to help her give you clearer answers.

Because a young infant’s illness can rapidly develop into serious life-threatening conditions, effective communication skills with the mother are crucial when assessing her young infant. In the next section you are going to look at the steps you need to follow when assessing a young infant.

3.2 Assessment

Depending on whether it is an initial visit or a follow-up visit, there is a sequence of steps that you need to follow to assess a young infant. The assessment steps described below must be done for every sick young infant. First, you are going to look at how to conduct an initial visit assessment.

3.2.1 Initial visit assessment

To assess a young infant you should:

- Check for signs of possible bacterial infection and jaundice.

- Ask about diarrhoea. If the infant has diarrhoea, assess the related signs, including whether the young infant is dehydrated. Also classify whether the diarrhoea is persistent and whether dysentery is present (you will learn how to assess for dysentery in Study Session 5 of this Module).

- Check for feeding problems or low weight. This includes assessing breastfeeding (which you will learn in Study Session 5 of this Module).

- Check the young infant’s immunization status (which you will learn in Study Session 12 of this Module).

- Assess any other problems, for example birth trauma and birth defects.

If it is clear that a young infant needs urgent referral, because you have classified serious bacterial infection or jaundice or another serious illness, there may not be time to do the breastfeeding assessment.

You need to be aware of the importance of assessing the signs in the order set out in Box 3.1 below, and to keep the young infant calm while you do the assessment. The young infant may be asleep while you assess the first three signs: that is, counting breathing, looking for chest in-drawing and grunting. When you assess the signs in relation to the umbilicus, temperature, skin pustules and jaundice, you will need to pick up the infant and then undress him, so that you can look at the skin all over his body and measure his temperature. By this time he will probably be awake so you can then observe his movements.

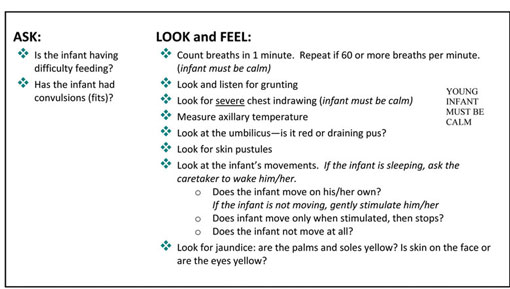

Box 3.1 sets out the steps you need to take to assess the young infant for bacterial infection and jaundice at the initial visit.

Box 3.1 How to check for possible bacterial infection and jaundice at an initial visit

You are now going to look at each of these steps in more detail, first in relation to assessing for bacterial infection.

3.3 Assess for bacterial infection

There are a number of questions you should ask, and signs that you should look for, to assess whether or not a young infant or child has bacterial infection. For example:

ASK: Is there any difficulty feeding?

Ask the mother this question. Any difficulty mentioned by the mother is important. She may need counselling or specific help with any problems she is experiencing when feeding her baby. If the mother says that the young infant is not able to feed, assess breastfeeding or watch her try to feed the young infant with a cup to see what she means by this. Any young infant who is not able to feed may have a serious infection or other life-threatening problem.

ASK: Has the infant had convulsions?

Convulsions can be generalised or focal (an abnormal body movement that is limited to one or two parts of the body, such as twitching of the mouth and eyes, arms or legs). Focal convulsions can be faint and can easily be missed. They can present with twitching of the fingers, toes or mouth or rolling of the eyes.

LOOK: Count the breaths in one minute. Repeat the count if the infant’s breathing is fast

You must count the breaths the young infant takes in one minute to decide if the infant has fast breathing. Sixty breaths per minute or more is the cut-off used to identify fast breathing in a young infant. The child must be quiet and calm when you look at and listen to his breathing. Tell the mother you are going to count her infant’s breathing. Remind her to keep her infant calm. If the infant is sleeping, do not wake him.

To count the number of breaths in one minute:

- Use a watch with a second hand or a digital watch, look at the infant’s chest and count the number of breaths in 60 seconds.

- Look for breathing movement anywhere on the child’s chest or abdomen. You can usually see breathing movements even in an infant who is dressed. If you cannot see this movement easily, ask the mother to lift the infant’s shirt. If the infant starts to cry, ask the mother to calm the infant before you start counting.

If you are not sure about the number of breaths you counted (for example, if the infant was actively moving and it was difficult to watch the chest, or if the infant was upset or crying), repeat the count.

If the first count is 60 breaths or more, repeat the count. This is important because the breathing rate of a young infant is often irregular. A young infant will occasionally stop breathing for a few seconds, followed by a period of faster breathing. If the second count is also 60 breaths or more, the young infant has fast breathing.

LOOK for severe chest in-drawing

If you did not lift the infant’s shirt when you counted the infant’s breaths, ask the mother to lift it now.

Look for chest in-drawing when the infant breathes in. Look at the lower chest wall (lower ribs). The infant has chest in-drawing if the lower chest wall goes in when the infant breathes in. Chest in-drawing occurs when the effort the infant needs to breathe in is much greater than normal. In normal breathing, the whole chest wall (upper and lower) and the abdomen move out when the infant breathes in. When chest in-drawing is present, the lower chest wall goes in when the infant breathes in. Chest in-drawing is also known as subcostal in-drawing or subcostal retraction.

If you are not sure that chest in-drawing is present, look at the infant again. If the infant’s body is bent at the waist, it is hard to see the lower chest wall move. Ask the mother to change the infant’s position so he is lying flat in her lap. If you still don’t see the lower chest wall go in when the infant breathes in the infant does not have chest in-drawing.

For chest in-drawing to be present, it must be clearly visible and present all the time. If you only see chest in-drawing when the infant is crying or feeding, the infant does not have chest in-drawing.

If only the soft tissue between the ribs goes in when the child breathes in (also called intercostal in-drawing or intercostal retraction), the infant does not have chest in-drawing.

Mild chest in-drawing is normal in a young infant because the chest wall is soft. Severe chest in-drawing is very deep and easy to see. Severe chest in-drawing is a sign of pneumonia and is serious in a young infant.

How do you decide whether a two-week-old infant has a mild or severe chest in-drawing?

If you look carefully at the young infant’s bare chest and see the lower chest wall going in when the infant breathes in, and the infant is calm, you will know this is severe chest in-drawing. It is more than the mild chest in-drawing you might see simply because the chest wall is soft in a young infant.

LOOK and LISTEN for grunting

Grunting is the soft, short sounds a young infant makes when breathing out. Grunting occurs when an infant is having trouble breathing.

LOOK at the umbilicus — is it red or draining pus?

There may be some redness of the end of/around the umbilicus or the umbilicus may be draining pus (Figure 3.1). The cord usually drops from the umbilicus by one week of age.

Feel and measure

Measure the axillary (underarm) temperature (or feel for fever or low body temperature). Fever (where the axillary temperature is 37.5°C or more) is uncommon in the first two months of life. If a young infant has a fever, this may mean the infant has a serious bacterial infection. A fever may be the only sign of a serious bacterial infection. Young infants can also respond to infection by developing hypothermia (dropping of body temperature to below 35.5°C). Low body temperature is defined as body temperature between 35.5 and 36.4°C.

If you do not have a thermometer, feel the infant’s stomach or axilla (underarm) and determine if it feels hot or unusually cool.

LOOK for skin pustules

Examine the skin on the entire body. Skin pustules are red spots or blisters which contain pus.

LOOK at the young infant’s movements. Are they fewer than normal?

Young infants often sleep most of the time, and this is not a sign of illness. Even when awake, a healthy young infant will usually not watch the mother and a health worker while they talk, as an older infant or young child would. If a young infant does not wake up during the assessment, ask the mother to wake him.

A young infant who is awake will normally move his arms or legs or turn his head several times in a minute if you watch him closely. You should observe the infant’s movements while you do the assessment. Look and see if the young infant moves when gently shaken by the mother, or when you clap your hands or gently stimulate the young infant. If the young infant moves only when stimulated, or does not move even when stimulated, this is a sign that the young infant could have an infection.

3.4 Assess for jaundice

When you assess for jaundice, you look to see whether the child has yellow discolouration in the eyes and skin (for example, look at the infant’s palms and soles to see if they are yellow).

Jaundice is yellow discolouration of skin. Almost all newborns may have ‘physiological jaundice’ during the first week of life due to several physiological changes taking place after birth. Physiological jaundice usually appears between 48 and 72 hours of age; maximum intensity is seen on the fourth or fifth day (the seventh day in preterm newborns) and disappears by 14 days. It does not extend to the palms and soles, and does not need any treatment. However, if jaundice appears on the first day, persists beyond 14 days and extends to the young infant’s palms and soles of the feet, it indicates pathological jaundice, which could lead to brain damage.

To look for jaundice, you should press the infant’s forehead with your fingers to blanch the skin, then remove your fingers and look for yellow discolouration under natural light. If there is yellow discolouration, the infant has jaundice. Look at the eyes of the infant for yellowish discolouration as well. To assess for severity, repeat the process with the infant’s palms and soles too.

How would you look for jaundice in a newborn baby?

As you read, there are several ways you could do this, for example looking for signs on the infant’s forehead by pressing the skin there, and also looking at the infant’s eyes, palms and soles to see if there is any discolouration.

3.5 Classify bacterial infection and jaundice

If you have assessed a young infant as having bacterial infection and/or jaundice, you will need to classify the level of seriousness so you know whether to make an urgent referral for relevant medical treatment, or whether you can provide the right treatment yourself.

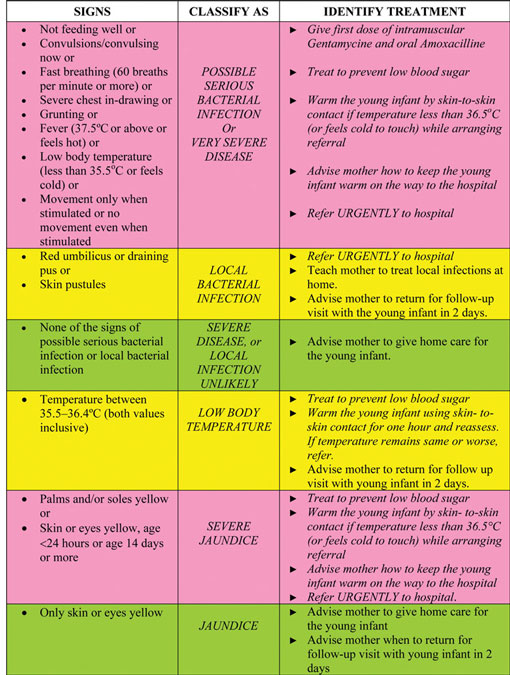

As you have learned in the study session on immediate newborn care, most classification tables have three rows. Classifications are colour-coded into pink, yellow or green. The colour of the row tells you if the young infant or the child has a serious illness. You can then quickly choose the appropriate treatment.

- A classification in the pink row means that the young infant needs urgent attention and referral or admission for in-patient care. This is a severe classification.

- A classification in the yellow row means that the young infant needs an appropriate antibiotic or other treatment. The treatment includes you teaching the mother how to give the oral drugs or to treat local infections at home and advising her about caring for the young infant at home and when she should return for a follow-up visit.

- A classification in the green row means the young infant is unlikely to have serious bacterial infection and will therefore not need specific medical treatment such as antibiotics. You will need to teach the mother how to care for her young infant at home. For example, you might advise her on feeding her sick young infant or giving fluid for diarrhoea (you will find out more about how to advise and counsel the mother on treating her child at home in Study Session 14 in Part 2 of this Module).

When you are making the postnatal home visit on the third day, you find that the baby has a respiratory rate of 70 breaths per minute and an axillary temperature of 35°C. What other signs should you look for? How would you classify the baby’s illness?

You should ask whether the young infant is feeding poorly, check for severe chest in-drawing, look to see if the baby moves only when stimulated and check for jaundice. Even if the young infant has only two of these signs you would classify the case as possible serious bacterial infection or very severe disease.

In Table 3.1, you can see how bacterial infection and jaundice are classified according to particular signs in the young infant. The most urgent actions that need to be taken are in italics (in the third column).

Table 3.1 Classification and treatment of bacterial infection and jaundice.

3.6 Identify appropriate treatment

You are now going to learn how to identify and give pre-referral treatment when a young infant has signs of possible serious bacterial infection and how to treat the young infant who does not need referral. You will also look at how to treat for jaundice.

3.6.1 Possible serious bacterial infection or very severe disease

![]() A young infant with signs of possible serious bacterial infection may be at a high risk of dying.

A young infant with signs of possible serious bacterial infection may be at a high risk of dying.

An infant may have pneumonia, sepsis or meningitis, and it can be difficult to distinguish between these infections. It is not necessary for you to make this distinction, however, since your responsibility for a young infant with any sign of possible serious bacterial infection is to refer the young infant to hospital as a matter of urgency. Before referral, there are several things you can do to minimise the risk to the young infant’s health. For example:

- Give a first dose of intramuscular and oral antibiotics.

- Treat to prevent low blood sugar; this can be done by:

- the mother breastfeeding the child

- if the young infant is unable to breastfeed, offering expressed breastmilk or a breastmilk substitute

- offering sugar water if neither of the above options is available.

- The young infant should have 30‒50 ml of milk or sugar water before departure for medical treatment.

To make sugar water: Dissolve four level teaspoons of sugar (20 gm) in a 200 ml cup of clean water.

- Keep the young infant warm. Advising the mother to keep her sick young infant warm is very important. Young infants have difficulty in maintaining their body temperature. Low temperature alone can kill young infants.

Malaria is unusual in young infants, so you don’t need to give any treatment for possible severe malaria.

3.6.2 Local bacterial infection

Young infants with local bacterial infection usually have an infected umbilicus or a skin infection. The young infant needs to be referred to the health centre to get an appropriate oral antibiotic which can be administered by the mother for five days. The mother should therefore treat the local infection at home and give home care to her child and then return for a follow-up visit to the health post within two days to be certain the infection is improving. Bacterial infections can progress rapidly in young infants, so it is important that the mother understands she must return for you to check her young infant’s progress. You will learn in Study Session 14 of this Module how to teach mothers to treat local infections at home.

3.6.3 Severe disease or local infection unlikely

A young infant who is unlikely to have either severe disease or local infection does not require any specific treatment. Advise the mother to give home care for her young infant.

3.6.4 Low body temperature

In the absence of signs of possible serious bacterial infection and severe jaundice, if the axillary temperature of a young infant is between 35.5 and 36.4°C, the baby is probably not be sick enough to be referred. Low body temperature in such a case may be due to environmental factors and may not be due to infection. Such an infant should be warmed using kangaroo mother care (skin-to-skin contact) for one hour. First you should treat the young infant to prevent low blood sugar in one of the ways outlined above. You should reassess the young infant after one hour for signs of possible serious bacterial infection and record the infant’s temperature again.

3.6.5 Severe jaundice

A sick young infant with jaundice may have physiological jaundice. As you read earlier in this study session, this kind of jaundice can become worse, so you need to follow this up. You should give the mother advice on home care for the young infant, and ask her to return for a follow-up visit in two days so you can re-assess the level of jaundice present in the child.

A sick young infant with severe jaundice is at risk of suffering from bilirubin (a yellowish bile pigment that is an intermediate product of the breakdown of haemoglobin in the liver) which can cause brain damage. Therefore, you would need to refer a young infant with severe jaundice to an appropriate health facility for investigation and appropriate treatment. Before you arrange for the young infant to be referred to hospital you should ensure that he is treated to prevent low blood sugar, and that he is kept warm, both while referral is being arranged and on the way to the hospital.

Robel is a sick young infant with the classification possible serious bacterial infection or very severe disease and you decide that he needs urgent referral. What would you do before the mother takes Robel to the health centre?

The two main points to advise the mother are for her to breastfeed Robel or to give him expressed breastmilk to prevent low blood sugar, and to keep him warm to prevent low body temperature.

You are now going to do an activity which will help you to review the steps for assessing and classifying sick young infants and give you an opportunity to practise entering information about a young infant on a recording form.

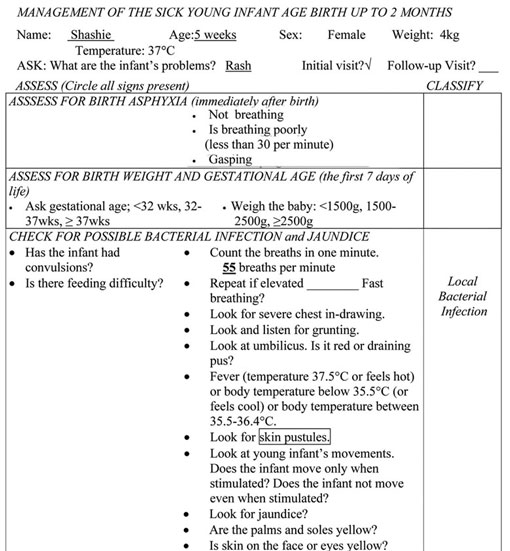

Activity 3.1 Assessing, classifying and recording information

A copy of a recording form has been reproduced in Box 3.2. Look at this form now. You will notice that the information which is required on the form is similar to that set out in the chart booklet in your health post. As you can see, details such as age, weight and temperature have been entered for the young infant Shashie, whose case is set out below (Case Study 3.1). Read Shashie’s case study now, and then look at how the recording form has been completed.

Case Study 3.1 Shashie’s story

Shashie is five weeks old. Her weight is 4 kg. Her axillary temperature is 37°C. Her mother brought her to the clinic because she has a rash. The health worker assesses for signs of possible bacterial infection. Shashie’s mother says that she hasn’t seen any convulsions. Shashie’s breathing rate is 55 per minute. She has no chest in-drawing, and no grunting. Her umbilicus is normal. The health worker examines Shashie’s entire body and finds a red rash with just a few skin pustules on her buttocks. Shashie is awake, and her movements are normal. She does not have diarrhoea.

When asked if Shashie has any difficulty feeding, the mother says no. She says that Shashie breastfeeds 9‒10 times in 24 hours and drinks no other fluids. The mother empties one breast before switching to the other and says that she breastfeeds Shashie more frequently during and after illness.

Box 3.2 Recording form for Shashie

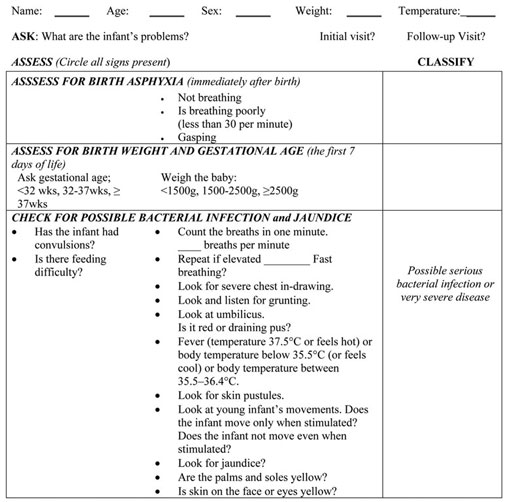

Now look at Case Study 3.2. Imagine you are the Health Extension Practitioner in this case and complete the recording form provided in Box 3.3 for Ababu.

- Label the recording form with the young infant’s name.

- From the case information, write the infant’s age, weight; temperature and problem and check the box for an ‘initial visit’.

- Record the assessment results on the form.

- Classify the infant for possible bacterial infection.

Case Study 3.2 Ababu’s story

Ababu is a three-week-old infant. His weight is 3.6 kg. His axillary temperature is 36.5ºC. He is brought to the health post because he is having difficulty breathing. You first check him for signs of possible bacterial infection. His mother says that Ababu has not had convulsions. You count 74 breaths per minute and repeat the count. The second count is 70 breaths per minute. He has mild chest in-drawing. He has no grunting, the umbilicus is normal and there are no skin pustules. Ababu is calm and awake, and his movements are normal. He does not have diarrhoea.

Box 3.3 Ababu’s record form

Comment

You should have recorded all of the information provided in the Case Study 3.2 on the recording form in Box 3.3. If you were not sure about how to do this you should talk to your Tutor at your next Study Support Meeting.

You are now going to look at the procedures you might follow if a young infant needs to be referred to hospital.

3.7 Referral

The procedures used for referring a young infant to hospital are the same as those for referring an older infant or young child. You need to prepare a referral note and explain to the mother the reason you are referring the young infant. You should also teach her anything she needs to do on the way, such as keeping the young infant warm, breastfeeding and giving sips of oral rehydration solution (ORS).

In addition, you should explain to the mother that young infants are particularly vulnerable. When they are seriously ill, they need hospital care and need to receive it promptly. Many cultures have reasons not to take a young infant to hospital. The mother may also be concerned about who is going to look after any other children at home if she is away. In all cases you will need to listen to the reasons and explain to the mother that her infant’s illness can best be treated at the hospital.

As you read earlier in this study session there are a number of situations where a young infant should be referred urgently to hospital. These include possible serious bacterial infection and severe jaundice (they also include asphyxia and low birth weight and when the baby is very preterm).

When referring a young infant urgently to hospital, there are a number of pre-referral treatments that you should give. You will find these urgent pre-referral treatments printed in bold on the chart booklet in your health post. Some treatments should not be given before referral because they are not urgently needed and would delay referral. For example, when you’re referring an infant urgently you would not spend time at that point teaching the mother how to treat a local infection, or giving the young infant immunizations.

3.7.1 Urgent pre-referral treatment

Urgent pre-referral treatments for a young infant are set out below (You will learn more about these in your practical skills training sessions.) You should:

- Give the first dose of intramuscular antibiotics.

- Give an appropriate oral antibiotic. If the infant needs an oral antibiotic for a local bacterial infection, give a first dose before referring the infant to the hospital.

- Advise the mother how to keep the infant warm on the way to the hospital. If the mother is familiar with wrapping her infant next to her body, this is a good way to keep him warm on the way to the hospital. Keeping a sick young infant warm is very important.

- Treat the young infant to prevent low blood sugar.

- Refer the young infant urgently to hospital, with the mother giving frequent sips of ORS on the way. For an infant with diarrhoea, advise the mother to continue breastfeeding.

3.7.2 Treatment for a young infant who does not need urgent referral

You can identify the appropriate treatment for each classification by reading the chart in your health post. You should enter on the record form what treatment you give the young infant. When you advise the mother on how to care for her young infant at home you should also tell her when she needs to return for a follow-up visit. A young infant who receives antibiotics for local bacterial infection should return for a follow-up visit in two days.

Follow-up visits are especially important for a young infant. If you find at the follow-up visit that the infant’s condition is worse, you must refer the infant to the hospital.

Oral antibiotics

For local bacterial infection you should give the young infant an appropriate oral antibiotic. Give amoxicillin as indicated in Table 3.2 below. However you should avoid giving cotrimoxazole to infants less than one month of age who are premature or jaundiced. Instead you should give the young infant amoxicillin.

AGE or WEIGHT | AMOXYCILLIN Give three times daily for five days | |

|---|---|---|

TABLET 250 mg | SYRUP 125 mg in 5 ml | |

Birth up to one month (<3 kg) |

| 1.25 ml |

One month up to two months (3‒4 kg) | ¼ | 2.5 ml |

Give first dose of intramuscular antibiotics

Table 3.3 below sets out the appropriate dose of intramuscular gentamycin that you should give the young infant with possible serious bacterial infection or very severe disease.

| WEIGHT | GENTAMYCIN Dose: 2.5 mg per kg body weight (IM) |

|---|---|

Use the undiluted 20 mg/2 ml formulation or dilute the 80 mg/2 ml formulation by adding 6 ml of sterile water | |

1 kg | 0.25 ml* |

2 kg | 0.50 ml* |

3 kg | 0.75 ml* |

4 kg | 1.00 ml* |

5 kg | 1.25 ml* |

Footnotes

*Avoid using undiluted 40 mg/ml Gentamycin. The dose is a quarter of that listed above and will be very difficult to measure accurately.Referral is always the best option for a young infant classified with possible serious bacterial infection. However as taking the child to hospital is not always an option, or if you know that the mother is unlikely to take the child to hospital, the guidelines on Where referral is not possible state that you should advise the mother that she must treat the young infant with amoxycillin every eight hours and gentamycin every 12 hours for at least seven days. You would also tell her to come back for a follow-up visit in two days, so that you can check whether the infant is making progress. When the baby is a newborn you should explain to the mother the circumstances when she should bring her baby back to the health post immediately.

3.8 Follow-up visits and care for the sick young infant

Follow-up visits are recommended for young infants who are classified as having local bacterial infection and jaundice. You assess a sick young infant differently at a follow-up visit from how you do at an initial visit. Once you know that the young infant has been brought to the clinic for a follow-up visit, you should ask the mother whether there are any new problems. If the infant has a new problem then you should carry out a full assessment as if it were an initial visit.

If the young infant does not have a new problem and was previously assessed as having a local bacterial infection then you should follow the steps outlined in Box 3.4 below.

The instructions for follow-up care of local bacterial infection and jaundice can be found in the ‘young infant’ chart.

Box 3.4 Follow-up care for a young infant with local bacterial infection

Two days after initial assessment:

- Look at the umbilicus. Is it red or draining pus? Does the redness extend to the skin?

- Look at the skin pustules. Are there many or severe pustules?

Treatment:

- If the pus or redness remains the same or is worse, refer the infant to hospital.

- If the pus and redness have improved, tell the mother to continue giving the five days of antibiotic and treating the local infection at home.

If the young infant was previously assessed for jaundice, follow the steps in Box 3.5 below.

Box 3.5 Follow-up care for a young infant with jaundice

If the young infant was previously assessed as having jaundice then you should follow the steps outlined below.

Two days after initial assessment:

- Check for danger signs in the newborn

- Counsel and support optimal breastfeeding

- Follow-up of kangaroo mother care

- Follow-up of counselling given during previous visits

- Counsel mother/family to protect baby from infection

- Give one capsule of 200,000 IU vitamin A to the mother if not given before

- Immunize the baby with OPV and BCG if not given before.

Ask about new problems.

Look for jaundice — are the palms and soles yellow?

- If the palms and soles are yellow, or the infant is aged 14 days or more, refer the infant to hospital.

- If the palms and soles are not yellow and the infant is less than 14 days old, and jaundice has not decreased, advise the mother on home care, when to return immediately and ask her to return for a follow-up visit in two days.

- If the jaundice has started decreasing, reassure the mother and ask her to continue home care. Ask her to return for a follow-up visit when the infant is two weeks old. If the jaundice continues beyond two weeks of age, refer the infant to the hospital.

In this section you have looked at how to provide follow-up care for the sick young infant. During the follow-up visit you should see if the mother is following your advice from the previous visits and ask her if there any new problems. If there are, then you will need to do another full assessment of the young infant.

Summary of Study Session 3

In Study Session 3, you have learned that:

- There are certain assessment steps that you must carry out for every sick young infant so you can identify the signs of bacterial infections, especially a serious infection, and jaundice.

- A young infant can become sick and die very quickly from serious bacterial infections such as pneumonia, sepsis and meningitis.

- Any one of the following signs are signs of possible serious bacterial infections or very severe disease: not feeding well, convulsions, fast breathing, severe chest in-drawing, grunting, fever or low temperature and the infant moving only when stimulated or not moving even when stimulated.

- Assessment, classification and treatment of young infants with local bacterial infections and jaundice are key tasks for a Health Extension Practitioner.

- You must enter relevant information on the young infant recording form.

- You should give follow-up care, two days after the initial visit, for a young infant who has local bacterial infection and/or jaundice.

- Effective communication with the mother is an important part of being able to carry out assessment of a young infant and when discussing with the mother how a young infant can be treated at home.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 3

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

You will recall reading about Shashie in Activity 3.1 in this study session. We have reproduced the facts of her case here and you can also look back to Case Study 3.1 in this study session to remind yourself where the information about Shashie was entered on her recording form.

Read the Case Study 3.3 below and then answer the questions that follow.

Case Study 3.3 for SAQ 3.1

Shashie is five weeks old. Her weight is 4 kg and her axillary temperature is 37°C. Her mother has brought her to the clinic because she has a rash. You assess her for signs of possible bacterial infection. Shashie’s mother says that the baby has not had any convulsions. Her breathing rate is 55 per minute; she has no chest in-drawing and is not grunting. Her umbilicus is normal. You examine her entire body and find a red rash with just a few skin pustules on her buttocks. Shashie is awake, and her movements are normal. She does not have diarrhoea.

SAQ 3.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.1, 3.2, 3.6, and 3.7)

- a.How would you classify Shashie’s illness and how would you treat her?

- b.What advice would you give to the mother about how she should treat Shashie at home?

- c.When should Shashie return for a follow-up visit?

Answer

- a.You should have classified Shashie as having a local bacterial infection that can be treated by giving her antibiotics. You should have noted that Shashie also needs treatment at home for the pustules on her buttocks.

- b.Your advice to the mother would include telling her that it is always important to wash her hands when treating Shashie’s skin pustules. You would explain to her that she should treat Shashie twice a day and show her how to gently wash the pus and crusts with soap and water then dry the area before painting it with 0.5% gentian violet. Tell the mother that she should wash her hands again after giving this treatment to prevent spreading the infection to herself or anyone else she comes into contact with. You might also have remembered that you should tell the mother to breastfeed Shashie exclusively at least eight times in every 24 hours on demand and that it is important for her to keep Shashie warm. If the weather is cool, the mother can keep her young infant warm by covering her head and feet and dressing her in extra clothing.

- c.The mother should return for a follow-up visit immediately if Shashie shows signs of feeding poorly, becomes sicker, develops a fever or feels cold to touch, develops fast breathing, difficult breathing, blood in stool, deepening of yellow colour of the skin, redness, swollen discharging eyes, redness, pus or foul odour around the cord. Otherwise, she should return for a follow-up visit two days after the initial one.

Read this Case Study 3.4 and then answer the questions below.

Case Study 3.4 for SAQ 3.2

Robel is a five-day old, full term newborn whose weight is 3 kg, axillary body temperature 38.5°C. He is attending the health post for an initial visit. When you ask the mother what the problem is, she tells you that her baby is breathing with difficulty and that he has stopped breastfeeding. When you ask her if he has had convulsions she answers no. When you examine Robel for possible bacterial infection, he is breathing 80 breaths in one minute. When you count again, his breathing rate is still 80 in one minute; in addition you can hear he is grunting. Robel does not move even when you stimulate him, and the palms of his hands and soles of his feet are yellow. There are no other signs of illness.

SAQ 3.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4 and 3.5)

- a.How would you classify Robel’s illness and what would you do next?

- b.Write a referral note for Robel which you will show to your clinical mentor for comment at your IMNCI practical skills training session.

Answer

- a.You should have classified Robel’s illness as possible serious bacterial infection or very severe disease and severe jaundice. He will need urgent hospital treatment. However, before sending Robel to the health centre or hospital there are life-saving actions that you would take (i.e. give Robel pre-referral oral Amoxicillin and Gentamycine injection as well as treat him to prevent low blood sugar). You would need to explain to the mother the need for referral and that her baby will receive better care at the health centre or hospital. You would also need to advise the mother how to keep her young infant warm on the way to hospital.

- b.Show Robel’s referral form to your clinical skills mentor.