Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 8 March 2026, 9:23 AM

Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness Module: 5. Management of Diarrhoeal Disease in Young Infants and Children

Study Session 5. Management of Diarrhoeal Disease in Young Infants and Children

Introduction

If you have access to your Assess and Classify booklet you should have the section on diarrhoea open for this study session.

You may recall from Study Session 1 of this Module that diarrhoea is the second most important cause of death among children under the age of five years. As a Health Extension Practitioner, therefore, you need to know how to assess and classify a sick child with diarrhoea. This study session includes case studies based on common experiences which will also help you understand how to treat a sick child with diarrhoea and what follow-up care is required. This study session is in two parts; the first six sections deal with management of diarrhoeal disease in children and the last section looks at how you manage diarrhoea in young infants. Although the classification is the same for both age groups, the treatment is different and you need to be aware of this difference.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 5

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

5.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 5.1, 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4)

5.2 Assess a child presenting with diarrhoea. (SAQ 5.1)

5.3 Classify the illness in a child who has diarrhoea. (SAQs 5.2 and 5.3)

5.4 Treat the child with diarrhoea. (SAQ 5.3)

5.5 Give follow-up care for a child with diarrhoea. (SAQ 5.3)

5.1 Assess and classify diarrhoea

There are different kinds of diarrhoea and you will need to know how to identify and assess these. Diarrhoea may be loose or watery, with blood in the stool and may be with or without mucus. It frequently leads to dehydration in the child, and can be serious enough to lead not only to malnutrition but also to the child’s death. It may be acute or persistent (you will learn about the difference between these below) and can be linked to a number of diseases, including cholera and dysentery. The most common cause of dysentery is Shigella bacteria (amoebic dysentery is not common in young children).

Shigella bacteria and other infectious agents that cause diarrhoea are described in Study Sessions 32 and 33 of the Communicable Diseases Module.

A child may have both watery diarrhoea and dysentery. The death of a child with acute diarrhoea is usually due to dehydration.

- Diarrhoea is the passage of three or more loose or watery stools per day.

- Persistent diarrhoea: diarrhoea which lasts 14 days or more (in a young infant this would be classified as severe persistent diarrhoea).

- Dysentery: diarrhoea with blood in the stool, with or without mucus.

5.2 Assess diarrhoea in children

All sick children that come to your health post should be checked for diarrhoea.

ASK: Does the child have diarrhoea?

- If the mother answers no, ask about the next main symptom, fever. You do not need to assess the child further for signs related to diarrhoea.

- If the mother answers yes, or if the mother said earlier that diarrhoea was the reason for coming to the health post, record her answer. Then assess the child for signs of dehydration, persistent diarrhoea and dysentery.

You need to assess the following:

- How long the child has had diarrhoea

- Whether there is blood in the stool to determine if the child has dysentery, and

- Any signs of dehydration.

Box 5.1 sets out the signs you need to ask about and look for when assessing a child who has diarrhoea.

Box 5.1 Assessing diarrhoea in a child

| Does the child have diarrhoea? IF YES ASK: | LOOK AND FEEL |

|---|---|

● For how long? ● Is there blood in the stool? | ● Look at the child’s general condition. Is the child: - Lethargic or unconscious? - Restless and irritable? - Look for sunken eyes. ● Offer the child fluid. Is the child: - Not able to drink or drinking poorly? - Drinking eagerly, thirsty? ● Pinch the skin of the abdomen. Does it go back: - Very slowly (longer than two seconds)? - Slowly? |

You will now look at the steps for assessing diarrhoea in a child in more detail.

ASK: For how long has the child had diarrhoea?

- Give the mother time to answer the question. She may need time to recall the exact number of days.

ASK: Is there blood in the stool?

- Ask the mother if she has seen blood in the stools at any time during this episode of diarrhoea.

Next, you need to check the child for signs of dehydration.

A child who becomes dehydrated is at first restless and irritable. If dehydration continues, the child becomes lethargic or unconscious. As the child’s body loses fluids, the eyes may look sunken. When pinched, the skin will go back slowly or very slowly. To assess whether the child is dehydrated, and how seriously, you need to look and feel for the following signs.

LOOK at the child's general condition

LOOK to see if the child is lethargic or unconscious. Or, is the child restless and irritable?

When you checked for general danger signs, you checked to see if the child was lethargic or unconscious. If the child is lethargic or unconscious, he has a general danger sign. Remember to use this general danger sign when you classify and record the child’s diarrhoea.

![]() If a child is lethargic or unconscious this is a general danger sign.

If a child is lethargic or unconscious this is a general danger sign.

The sign restless and irritable is present if the child is restless and irritable all the time or every time he is touched and handled. If an infant or child is calm when breastfeeding, but again becomes restless and irritable when breastfeeding stops, he has the sign ‘restless and irritable’. However, many children are upset just because they are in the health post and in unfamiliar surroundings. Usually these children can be consoled and calmed. They do not have the sign ‘restless and irritable’.

LOOK for sunken eyes

- The eyes of a child who is dehydrated may look sunken. Decide if you think the eyes are sunken. Then ask the mother if she thinks her child’s eyes look unusual. Her opinion helps you confirm whether the child’s eyes are sunken.

- You should note that in a severely malnourished child who is visibly wasted, the eyes may always look sunken, even if the child is not dehydrated. However, although sunken eyes is less reliable in a visibly wasted child, you should still use the sign to classify the child’s dehydration.

OFFER the child fluid. Is the child not able to drink or drinking poorly? Or, is the child drinking eagerly, thirsty?

- Ask the mother to offer the child some water in a cup or spoon. Watch the child drink. A child is not able to drink if he is not able to suck or swallow when offered a drink. A child may not be able to drink because he is lethargic or unconscious.

- A child is drinking poorly if the child is weak and cannot drink without help. He may be able to swallow only if fluid is put in his mouth.

- A child has the sign drinking eagerly, or thirsty if it is clear that the child wants to drink. Look to see if the child reaches out for the cup or spoon when you offer him water. When the water is taken away, see if the child is unhappy because he wants to drink more.

- If the child takes a drink only with encouragement and does not want to drink more, or refuses to drink, he does not have the sign ‘drinking eagerly, thirsty’.

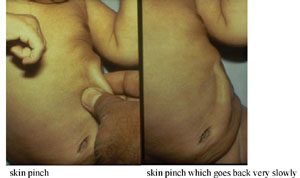

PINCH the skin of the abdomen. Does it go back very slowly (longer than two seconds) or slowly?

- Ask the mother to place the child on the examining table so that the child is flat on his back with his arms at his sides (not over his head) and his legs straight. Or, ask the mother to hold the child so he is lying flat on her lap. Locate the area on the child’s abdomen halfway between the umbilicus and the side of the abdomen. To do the skin pinch, use your thumb and first finger. Do not use your fingertips because this will cause pain. Place your hand so that when you pinch the skin, the fold of skin will be in a line up and down the child’s body and not across the child’s body. Firmly pick up all of the layers of skin and the tissue under them. Pinch the skin for one second and then release it. If the skin stays up for even a brief time after you release it, decide that the skin pinch goes back slowly.

- When you release the skin, look to see if the skin pinch goes back:

- very slowly (longer than two seconds)

- slowly

- immediately.

The photographs in Figure 5.1 show you how to do the skin pinch test and what the child’s skin looks like when the skin pinch does not go back immediately.

The skin pinch test is not always an accurate sign of dehydration because in a child with severe malnutrition, the skin may go back slowly even if the child is not dehydrated. In an overweight child, or a child with oedema, the skin may go back immediately even if the child is dehydrated. However even though skin pinch is less reliable in these children, you should still use it to classify the child's dehydration.

What are the possible assessments you might make for a child with diarrhoea?

You might assess the child for dehydration. If the child has had diarrhoea for 14 days or longer you would assess persistent diarrhoea, and if you see blood in the stool or if the mother tells you that there has been blood in the stool, you would record that the child might have dysentery.

How can you assess whether a child has dehydration?

If the child is irritable and restless, not able to drink or drinks poorly, these are all signs of dehydration. Another sign is a skin pinch that returns slowly or very slowly. You should also remember that if a child is lethargic or unconscious this is one of the general danger signs as well as a possible sign of dehydration.

Following your assessment of the child for diarrhoea and dehydration, your next step is to classify the diarrhoea. How you do this will depend on the age of the child, and you are going to look at this next.

5.3 Classifying diarrhoea

There are three classification tables for classifying diarrhoea:

- All children with diarrhoea are classified for dehydration.

- If a child has had diarrhoea for 14 days or more, the child should be classified as having persistent diarrhoea.

- If a child has blood in the stool, the child should be classified as having dysentery.

You are now going to look at each of these classifications in turn, beginning with classifying dehydration.

5.3.1 Classifying dehydration

There are three possible classifications of dehydration in a child with diarrhoea:

- Severe dehydration

- Some dehydration

- No dehydration.

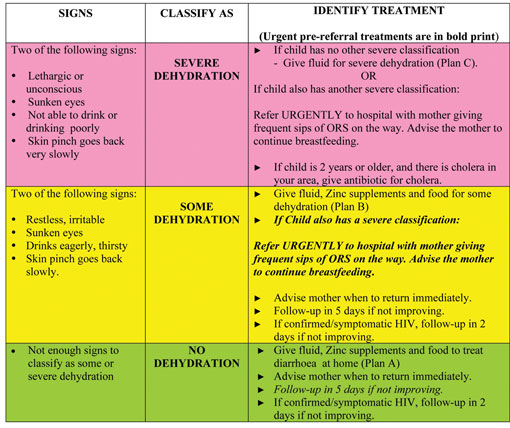

The relevant section from the Assess and Classify chart booklet is set out in Table 5.1. The treatment plans A, B and C referred to in the third column are explained in Section 5.4 below.

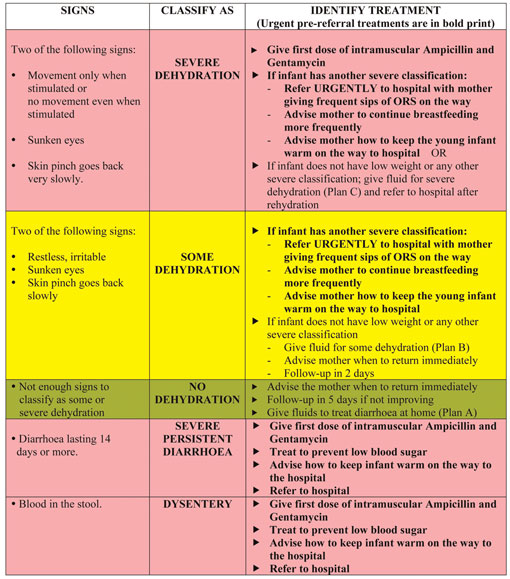

Table 5.1 Classification of dehydration in a child (1).

To classify the child’s dehydration, begin with the top (pink) row.

- If two or more of the signs in the pink row are present, you should classify the child as having SEVERE DEHYDRATION.

- If two or more of the signs are not present, look at the middle (yellow) row. If two or more of the signs are present, you should classify the child as having SOME DEHYDRATION.

- If two or more of the signs from the yellow row are not present, classify the child has having NO DEHYDRATION (bottom, green row). The child does not have enough signs to be classified as having SOME DEHYDRATION.

Case Study 5.1 below provides an example for you to see how you would classify a child in practice.

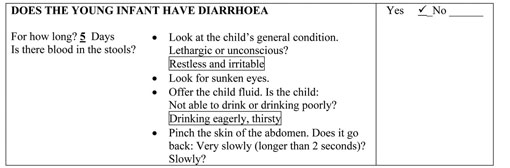

Case Study 5.1 Amina’s story

A four-month-old child named Amina was brought to the health post because she had had diarrhoea for five days. She did not have danger signs and she was not coughing. However Amina was restless and irritable every time the health worker touched her and would not settle even when her mother tried to soothe her. The only time she was calm was when her mother was breastfeeding her. Amina was able to feed strongly. The health worker assessed the child’s diarrhoea. She recorded the following signs:

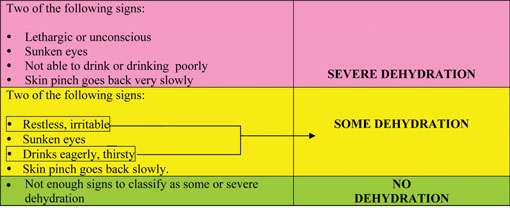

Look at Table 5.2 below. Amina does not have any signs in the pink row. Therefore Amina does not have SEVERE DEHYDRATION.

Table 5.2 Classification of dehydration in a child (2).

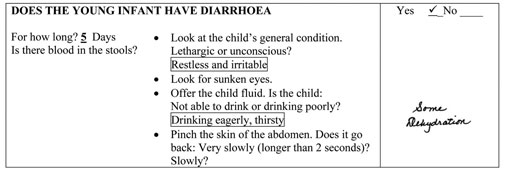

Amina had two signs from the yellow row. Therefore the health worker classified Amina's dehydration as SOME DEHYDRATION.

The health worker recorded Amina’s classification on the recording form which is reproduced in Box 5.2 below.

Box 5.2 Recording form for Amina

Now complete Activity 5.1.

Activity 5.1 How to assess a child with severe dehydration

Look back at Table 5.1 and answer the following questions.

- a.Describe the signs that would lead you to assess a child as having severe dehydration.

- b.How would you know if the child had some dehydration?

- c.What classification would you give for a child who has sunken eyes, appears restless and irritable except when breastfeeding and whose skin pinch goes back slowly? Give reasons for your answer.

Comment

- a.As you can see from the top (pink) row in Table 5.1, if the child has any two of the signs in this row then you should classify the child as having severe dehydration. One of the signs is ‘lethargic or unconscious’ and you should remember that this is also a general danger sign and requires the child to be referred urgently.

- b.The middle row (yellow) sets out the signs leading to classification of ‘some dehydration’. You should remember however that even if a child does not have signs of dehydration it does not mean that the child has not lost fluids. If the diarrhoea persists, dehydration is a risk to the child so you should advise the mother when she should return to the health post.

- c.A child with the signs in (c) above has one sign from the top (pink) row and has three signs from the middle (yellow) row. Therefore you should classify this child as having some dehydration.

You are now going to look at what treatment can be provided for a child with diarrhoea, depending on the level of dehydration you have classified.

5.4 Treatment for dehydration

There are three treatment plans for treating children with dehydration and for diarrhoea: Plan C sets out the steps for treating children with severe dehydration, Plan B is for children with some dehydration, and Plan A sets out home treatment for children with diarrhoea but no dehydration.

First you are going to look at how to treat severe dehydration, using Plan C.

5.4.1 Severe dehydration

Any child with dehydration needs fluid replacement. A child classified with severe dehydration needs fluids quickly. ‘Plan C: Treat Severe Dehydration Quickly’ describes how to give fluids to severely dehydrated children and is set out in Box 5.3 below.

Note that giving intravenous (IV) fluid therapy through a sterile tube and cannula into a small child’s vein requires special training in addition to any training you may have received on giving IV fluids to adults.

Box 5.3 Plan C: Steps for treating severe dehydration

Activity 5.2 Steps for treating severe dehydration

Look at the information in Box 5.3 and then make notes in your Study Diary in answer to the following questions.

- a.When should you refer a child urgently to hospital for treatment?

- b.If there is no IV line available, or you have not been trained to insert one, what options could you follow?

- c.How often would you assess the child after rehydration? Give reasons for your answer.

Comment

![]() If IV fluid cannot be given immediately to a child with severe dehydration, but treatment is available nearby, you should refer the child urgently.

If IV fluid cannot be given immediately to a child with severe dehydration, but treatment is available nearby, you should refer the child urgently.

You can see that the guidance in Box 5.3 sets out a series of questions that take you through a range of options depending on your training and what resources are available in your health post, such as IV fluids or naso-gastric (NG) tube. The essential points are these:

- a.A child with severe dehydration needs to be treated as quickly as possible.

- b.If you are not able to rehydrate the child using an IV line, naso-gastric tube, or because the child is unable to take fluids by mouth, you must refer the child urgently to a hospital.

- If there is an IV facility which the mother can reach in less than 30 minutes you should refer the child urgently, giving sips of ORS during the trip.

- If the health facility is more than 30 minutes away you should still refer if you are not able to rehydrate the child using a naso-gastric tube or orally.

- c.If you are able to rehydrate the child but his hydration status does not improve after three hours, you should refer the child.

You are now going to look at how to treat a child classified with some dehydration.

5.4.2 Some dehydration

Although this is not as serious as ‘severe dehydration’ it is still important that you treat a child who has ‘some dehydration’ in order to prevent his situation becoming worse. Box 5.4 below sets out Plan B: the steps to take to treat a child with some dehydration.

Box 5.4 Plan B: Treatment of a child with some dehydration

Give in clinic recommended amount of ORS over 4-hour period DETERMINE AMOUNT OF ORS TO GIVE DURING FIRST 4 HOURS | ||||

| AGE | Up to 4 Months | 4 months up to 12 months | 12 months up to 2 years | 2 years up to 5 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight in kg | < 6 kg | 6–10 kg | 10–12 kg | 12–19 kg |

| ORS in ml | 200–400 | 400–700 | 700–900 | 900–1400 |

Use the child’s age only when you do not know the weight. The approximate amount of ORS required (in ml) can also be calculated by multiplying the child’s weight (in kg) times 75. ● If the child wants more ORS than shown, give more. ● For infants under 6 months who are not breastfed, also give 100–200 ml clean water during his period. SHOW THE MOTHER HOW TO GIVE ORS SOLUTION. ● Give frequent small sips from a cup or cup and spoon (one spoon every 1–2 minutes). ● If the child vomits, wait 10 minutes. Then continue, but more slowly. ● Continue breastfeeding whenever the child wants. | ||||

AFTER 4 HOURS: ● Reassess the child and classify the child for dehydration. ● Select the appropriate plan to continue treatment. ● Begin feeding the child in clinic. | ||||

IF THE MOTHER MUST LEAVE BEFORE COMPLETING TREATMENT: ● Show her how to prepare ORS solution at home. ● Show her how much ORS to give to finish 4-hour treatment at home. ● Give her enough ORS packets to complete rehydration. Also give her a box of 10 packets of ORS as recommended in Plan A. ● Explain the 4 Rules of Home Treatment; these are: 1 GIVE EXTRA FLUIDS 2 GIVE ZINC SUPPLEMENTS 3 CONTINUE FEEDING 4 WHEN TO RETURN | ||||

5.4.3 No dehydration

A child with diarrhoea, even if classified as having no dehydration, still needs extra fluid to prevent dehydration occurring. A child who has no dehydration needs home treatment and the steps for this are set out in Plan A in Box 5.5.

Box 5.5 Plan A: Treatment for a child with diarrhoea but no dehydration

Give Extra Fluids, Give Zinc Supplements, Continue Feeding, When to Return 1 Give extra fluids (as much as the child will take): Tell the mother: – To breastfeed frequently and for longer at each feed. – If the child is exclusively breastfed, give ORS in addition to breastmilk. – If the child is not exclusively breastfed, give one or more of the following: ORS solution, food-based fluids (such as soup, rice water and yoghurt drinks), or clean water. It is especially important to give ORS at home when: – The child has been treated with Plan B or Plan C during this visit. – The child cannot return to a clinic if the diarrhoea gets worse. ● Teach the mother how to mix and give ORS. ● Give the mother 2 packets of ORS to use at home. ● Show the mother how much fluid to give in addition to the usual fluid intake: | ||

| Up to 2 years | 50 to 100 ml after each loose stool | |

| 2 years or more | 100 to 200 ml after each loose stool | |

Tell the mother to: – Give frequent small sips from a cup. – If the child vomits, wait 10 minutes. Then continue, but more slowly. – Continue giving extra fluid until the diarrhoea stops. | ||

2 Give zinc supplements: ● Tell the mother how much zinc to give: | ||

| Up to 6 months | 1/2 tablet for 10 days | |

| 6 months or more | 1 tablet for 10 days | |

● Show the mother how to give Zinc supplements – Infants — dissolve tablet in a small amount of expressed breastmilk, ORS or clean water in a cup; – Older children — tablets can be chewed or dissolved in a small amount of clean water in a cup. 3 Continue feeding 4 Tell her when to return | ||

You should now have a good understanding of how to treat a child with any of the three dehydration classifications. Next you are going to look at how to classify diarrhoea, beginning with persistent diarrhoea.

5.5 Classify persistent diarrhoea

After you have classified a child’s dehydration, you need to classify what kind of diarrhoea the child has. As you read earlier in this study session, a child who has had diarrhoea for 14 days or more should be classified as having persistent diarrhoea. There are two classifications of persistent diarrhoea, which are linked to the level of dehydration in the child (Box 5.6):

- severe persistent diarrhoea and

- persistent diarrhoea.

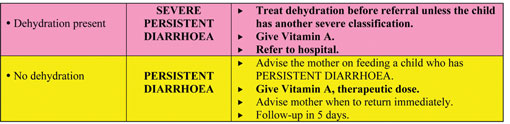

Box 5.6 Classification of persistent diarrhoea

5.5.1 Severe persistent diarrhoea

![]() A child who has had diarrhoea for 14 days or longer, and is also dehydrated, must be referred to hospital.

A child who has had diarrhoea for 14 days or longer, and is also dehydrated, must be referred to hospital.

If a child has had diarrhoea for 14 days or more and also has some or severe dehydration, you should classify the child’s illness as severe persistent diarrhoea.

Treatment

Children with diarrhoea lasting 14 days or more, who are also dehydrated, need to be referred to hospital. They may need laboratory tests of stool samples to identify the cause of the diarrhoea.

Treatment of dehydration in children with severe diarrhoea can be difficult and it is much more likely that a hospital will be able to treat such children more effectively. Therefore you should always refer these children, first giving a therapeutic dose of vitamin A before the child leaves your health post.

5.5.2 Persistent diarrhoea

A child who has had diarrhoea for 14 days or more but who has no signs of dehydration is classified as having persistent diarrhoea.

Treatment

Special feeding is the most important treatment for a child with persistent diarrhoea. Feeding recommendations for persistent diarrhoea are given in more detail later in this Module. Box 5.7 summarises how a child with persistent diarrhoea should be treated. You can see that it is important to treat the child with the recommended dose of vitamin A. Zinc supplements should also be given.

Box 5.7 Treatment for persistent and severe persistent diarrhoea.

| Give vitamin A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

For MEASLES, MEASLES with EYE/MOUTH complications and PERSISTENT DIARRHOEA give three doses. ● Give first dose in clinic. ● Give two doses in the clinic on days 2 and 15. | |||

For a child with SEVERE MALNUTRITION, SEVERE COMPLICATED MEASLES or SEVERE PERSISTENT DIARRHOEA give one dose in clinic and then refer. ● For a routine Vitamin A supplementation for children six months up to five years give one dose in clinic if the child has not received a dose within the last six months. | |||

| AGE | VITAMIN A CAPSULES | ||

| 200,000 IU | 100,000 IU | 50,000 IU | |

| Up to 6 months | ½ capsule | 1 capsule | |

| 6 months up to 12 months | ½ capsule | 1 capsule | 2 capsules |

| 12 months up to 5 years | 1 capsule | 2 capsules | 4 capsules |

5.5.3 Follow-up care for persistent diarrhoea

Children who have been classified with diarrhoea will need follow-up care to ensure that rehydration/hydration is maintained and to assess that the diarrhoea has stopped. You should give follow-up care after five days:

Ask:

- Has the diarrhoea stopped?

- How many loose stools is the child having per day?

Treatment:

![]() If diarrhoea does not stop after five days, do a full reassessment, treat and refer the child to hospital.

If diarrhoea does not stop after five days, do a full reassessment, treat and refer the child to hospital.

If the diarrhoea has not stopped (the child is still having three or more loose stools per day), do a full reassessment of the child, give any treatment needed and then refer the child to hospital.

If the diarrhoea has stopped (the child is having less than three loose stools per day), you should tell the mother to follow the usual feeding recommendations for the child’s age. You will learn more about feeding recommendations in Study Sessions 10 and 11 of this Module.

5.6 Classify dysentery

There is only one classification for dysentery; see Box 5.8 below:

Box 5.8 Classification for dysentery

Classify a child with diarrhoea and blood in the stool as having dysentery.

Treatment

You should treat the child’s dehydration in the same way as outlined earlier in this study session and give cotrimoxazole. Table 5.3 below sets out which antibiotics should be given and the correct dosage according to the weight (or age) of the child.

| Age (weight in kg) | Adult tablets | Paediatric tablets | Syrup in ml |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 months up to 12 months | ½ | 2 | 5 |

| 12 months up to 5 years | 1 | 3 | 7.5 |

5.6.1 Follow-up care for dysentery

For a child classified with dysentery, you need to provide follow-up care two days after the initial visit. Box 5.9 sets out the questions you need to ask at the follow-up care visit and what treatment should be provided. If you find the child’s symptoms are the same or have got worse, you should refer the child to hospital.

Box 5.9 Follow-up care for dysentery

Give follow-up care after two days as follows:

Ask:

- Are there fewer stools?

- Is there less blood in the stool?

- Is there less fever?

- Is there less abdominal pain?

- Is the child eating better?

Assess the child for diarrhoea. (Use the Assess and Classify chart to help you.)

Treatment:

- If the child is dehydrated, treat dehydration.

- If the number of stools, amount of blood in stools, fever, abdominal pain or eating problems are the same or worse: refer to hospital.

- If there are fewer stools, or there is less blood in the stools, less fever, less abdominal pain, and the child is eating better, continue giving the same antibiotic until finished. Review with the mother the importance of the child finishing the antibiotics.

5.7 Classify diarrhoea in young infants

![]() A young infant who has had diarrhoea lasting for 14 days or more should be referred to hospital.

A young infant who has had diarrhoea lasting for 14 days or more should be referred to hospital.

Diarrhoea in a young infant (below two months) is not classified in the same way as in an older infant or young child (two months to five years). The main difference is that for a young infant with diarrhoea lasting for 14 days or more the only classification is severe persistent diarrhoea. This is because 14 days represents a significant amount of time in a young infant’s life and they should be referred to hospital for treatment.

The main differences between classification and treatment for a young infant are the following:

- Movement only when stimulated or no movement even when stimulated (compared with lethargic or unconscious in a child).

- Treatment for a young infant with severe or some dehydration includes advising the mother how to keep her baby warm on the way to hospital.

- A young infant with diarrhoea lasting for 14 days or more is always classified as severe persistent diarrhoea (in a child, there also needs to be some or severe dehydration for a classification of severe persistent diarrhoea).

Table 5.4 sets out the classification and treatment of dehydration, dysentery and diarrhoea in the young infant. As you can see from Table 5.4, dysentery in a young child is a severe classification.

Table 5.4 How to classify and treat dehydration, diarrhoea and dysentery in a young infant.

In this study session you have looked at how to assess, classify and treat children and young infants with diarrhoea and dehydration. As you read in the introduction, diarrhoea is the second major cause of death in Ethiopia of children under five years old. Your role as a Health Extension Practitioner is therefore crucial in identifying the severity of the diarrhoea and dehydration in the sick child or young infant brought to your health post and in providing the best possible treatment and follow-up care for them. Knowing when to refer a child or young infant urgently to hospital is also important, since in some cases the special treatment available there is more likely to be effective than the treatment you can provide in a health post, in particular if you have limited resources available.

Summary of Study Session 5

In Study Session 5, you have learned that:

- Diarrhoea is a common illness among children under five years of age in Ethiopia.

- To assess diarrhoea in a child or young infant the steps you should take are:

- look for general danger signs

- ask for duration of diarrhoea

- assess for signs of dehydration

- ask about blood in the stool.

- Based on your findings on assessment, you classify the child for:

- Dehydration

- Persistent or severe persistent diarrhoea

- Dysentery.

- The classification and treatment in a child and a young infant are different; if a young infant has had diarrhoea for 14 days or more they should always be classified as having severe persistent diarrhoea.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 5

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 5.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3)

Why is it important to check for diarrhoea in all sick children who come to the health post?

Answer

All children must be checked because diarrhoea can lead to dehydration and is the second most important cause of death among children under five in Ethiopia.

SAQ 5.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 5.1, 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4)

Under what circumstances would you refer to hospital an infant or child who is dehydrated with diarrhoea or dysentery?

Answer

You should have thought of some of the following circumstances:

- If you have classified the child as having severe dehydration, the child is unable to take fluids by mouth, and you are not able to treat him yourself with an IV line or naso-gastric tube

- If you are able to rehydrate the child but his hydration condition does not improve after three hours

- If you have classified the child as having severe persistent diarrhoea (i.e. some dehydration and diarrhoea lasting more than 14 days)

- If a child has persistent diarrhoea and it has not stopped five days after treatment

- If a child with dysentery does not improve or gets worse after treatment

- If a young infant has diarrhoea for 14 days or more.

Read Case Study 5.2 and then answer the questions below.

Case Study 5.2 for SAQ 5.3

Sora is 10 months old. He weighs 8 kg. His temperature is 38.5°C. He is here today because he has had diarrhoea for three days. His mother has noticed blood in Sora’s stool. Sora does not have any general danger signs. He does not have cough or difficult breathing. The health worker assesses Sora for diarrhoea. He is not lethargic or unconscious. He is not restless or irritable. He does not have sunken eyes. Sora drank normally when offered some water and did not seem thirsty. The skin pinch goes back immediately.

SAQ 5.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 5.1, 5.3, 5.4 and 5.5)

- a.How do you classify Sora’s illness? Write down the reasons for your answer.

- b.How would you treat Sora and what advice would you give to the mother about follow-up care?

Answer

- a.The classification for Sora is dysentery. This is because he has had blood in his stool. Sora has only had diarrhoea for three days so he does not come within the classification of persistent diarrhoea. He does not have any of the signs for some or severe dehydration, so he would be classified as no dehydration.

- b.You should have written down the treatment for Sora as being the following:

- Cotrimoxazole: half adult tablet, or two paediatric tablets, or 5 ml syrup, twice daily for five days

- Give follow-up care after two days according to the guidelines in Box 5.9. Advise the mother to bring the child sooner if the symptoms get worse.