Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 3 December 2025, 2:06 AM

Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness Module: 6. Management of Sick Children with Fever

Study Session 6. Management of Sick Children with Fever

Introduction

Fever is a common symptom in many sick children. Think about your health post — many of the mothers who bring their children to see you are likely to say that the reason for their visit is that the child has fever. Being able to assess fever and classify the illness that is causing the fever is therefore an important task for you as a Health Extension Practitioner.

This study session will introduce you to the common causes of fever in children. A child with fever may just have a simple cough or other viral infection. However fever may also be caused by a more serious illness, such as malaria, measles or meningitis.

Malaria is a major cause of death in children so it is important that you are able to identify the symptoms and ensure the sick child receives urgent treatment as quickly as possible.

In this study session you will learn how to recognise and assess fever and which focused questions to ask so that you are able to classify the illness causing the fever. You will also learn how you treat the illness as effectively as possible and to support the mother in providing home care for her child.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 6

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

6.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 6.1 and 6.3)

6.2 Assess a child with fever. (SAQs 6.1, 6.2 and 6.3)

6.3 Classify the illness in a child with fever. (SAQs 6.2 and 6.3)

6.4 Treat and give follow-up care for very severe febrile illness, malaria, measles and other causes of fever. (SAQ 6.3)

6.1 Assess and classify fever

Malaria and measles are the two major illnesses where fever is likely to be a symptom (although you should not rule out either illness even if fever is not present).

Measles and malaria are both described in Communicable Diseases, Part 1; see Study Sessions 4 and 8 respectively.

Box 6.1 outlines the key symptoms and signs of malaria and the complications that can arise in an infant or child who has malaria.

Box 6.1 Malaria symptoms and possible complications

Fever is the main symptom of malaria. It can be present all the time or recur at regular intervals during the illness. Other signs of malaria are shivering, sweating and vomiting. A child with malaria may have chronic anaemia (with no fever) as the only sign of illness.

In areas with very high malaria transmission, malaria is a major cause of death in children. A case of uncomplicated malaria can develop into severe malaria within 24 hours of onset of the illness. The child can die if urgent treatment is not given.

Measles is another cause of fever. It is a highly infectious disease with most cases occurring in children aged between six months and two years. Box 6.2 below outlines the main symptoms and possible related infections that you need to be aware of if you are treating a child with measles.

Box 6.2 Measles: symptoms and complications

Fever and a generalised rash are the main signs of measles. Most cases occur in children between six months and two years of age. Measles is highly infectious. Overcrowding and poor housing increases the risk of measles occurring early in a child’s life.

Measles affects the skin and the layer of cells that line the lung, gut, eye, mouth and throat. The measles virus damages the immune system for many weeks after the onset of measles. This leaves the child at risk of other infections.

Complications of measles occur in many cases. The most important are: diarrhoea (including dysentery and persistent diarrhoea), pneumonia, stridor, mouth ulcers, ear infection and severe eye infection and blindness.

Measles also contributes to malnutrition because it causes diarrhoea, high fever and mouth ulcers, all of which can interfere with feeding. Malnourished children are more likely to have severe complications due to measles. This is especially true for children who are deficient in vitamin A. One in ten severely malnourished children with measles may die. For this reason, it is very important to help the mother to continue to feed her child during measles.

6.2 Assess fever

Whether or not the mother says the child has fever, it is important that you assess all sick children for fever.

A child has the main symptom of fever if:

- the child has a history of fever or

- the child feels hot or

- the child has an axillary temperature of 37.5°C or above.

ASK: Does the child have fever?

Check to see if the child has a history of fever, feels hot or has a temperature of 37.5°C or above.

The child has a history of fever if the child has had any fever with this illness. Use words for ‘fever’ that the mother understands. For example, ask the mother if the child’s body has felt hot. Feel the child’s abdomen or armpit and determine if the child feels hot.

If the child’s temperature has not been measured, and you have a thermometer, measure the child's temperature.

If the child has fever, assess the child for additional signs related to fever (if the child has no fever you should ask about the next main symptom, which is an ear problem. You will learn how to assess and classify ear problems in Study Session 13).

When a child presents with fever you should assess the child following the steps set out in Box 6.3 below. You will see that it lists the steps for assessing a child for fever and what the related illness may be.

The fontanelle is the ‘soft spot’ on top of an infant’s head where the skull bones have not yet fused. Meningitis is described in detail in Study Session 3 of Communicable Diseases, Part 1.

There are two parts to the box. The top section (above the broken line) describes how to assess the child for signs of malaria, measles, meningitis and other causes of fever. In meningitis there will be bulging fontanelle in infants and stiffness of the neck. The bottom section of the box describes how to assess the child for signs of measles complications if the child has measles now, or has had measles within the last three months.

Therefore, if your assessment is that the child does have fever, you should follow the steps in Box 6.3:

Box 6.3 Assessing for fever and possible related illnesses

Decide malaria risk: high or low or no.

If ‘low or no’ malaria risk, then ask:

- Has the child travelled outside this area during the previous 15 days?

- If yes, has the child been to a malarious area?

| THEN ASK | LOOK AND FEEL: |

|---|---|

● For how long has the child had fever? ● If more than seven days, has the fever been present every day? ● Has the child had measles within the last three months? | ● Look or feel for stiff neck ● Look or feel for bulging fontanelles (under one year old) ● Look for runny nose ● Look for signs of MEASLES ● Generalised rash and one of these: cough, runny nose, red eyes |

| If the child has measles now or within the last three months | ● Look for mouth ulcers Are they deep and extensive? ● Look for pus draining from the eye ● Look for clouding of the cornea |

You are now going to look in more detail at how to classify illnesses associated with fever.

6.2.1 Assessing for malaria

You need to decide whether the malaria risk is high or low. The practical criteria for classification of risk of malaria in Ethiopia, where malaria is seasonal, should be based on altitude and season.

- a.High risk: areas at altitude range of less than 2,000 metres above sea level, especially during the months of September to December and from April to June.

- b.Low risk: areas at altitude range of 2,000–2,500 metres above sea level, especially during the months of September to December and from April to June.

- c.No risk: areas at altitude range of above 2,500 metres above sea level.

If you are not sure whether the child has been to a malarious area you should assume the malaria risk is high.

If the malaria risk in the local area is low or absent, ask whether the child has travelled outside this area during the previous 15 days. If yes, then you should ask if the child has been to a malarious area. You should identify the malaria risk as high if there has been travel to a malarious area.

If the mother does not know or is not sure, ask about the area and use your own knowledge of whether the area has malaria. If you are still not sure, then you should assume the malaria risk is high.

Why do you think it is important to assess all sick children for fever?

Although fever may be caused by a simple cough or other virus infection, it can also be caused by a more serious illness, such as measles or malaria. As you read, malaria is a major cause of death for children so it is important than you know how to identify the signs.

6.2.2 Assessing for other diseases

If you assess the child as not having malaria, you need to consider other possible causes for the child’s fever.

ASK: How long has the child had fever?

If the fever has been present for more than seven days, ask if the fever has been present every day.

Most fevers due to a virus infection go away within a few days. A fever which has been present every day for more than seven days can mean that the child has a more severe disease. In this case you should refer the child for further assessment.

ASK: Has the child had measles within the last three months?

A child with fever and a history of measles within the last three months may have an infection due to complications of measles.

LOOK or FEEL for stiff neck

A child with fever and a stiff neck may have meningitis. A child with meningitis needs urgent treatment with injectable antibiotics and referral to a hospital.

While you talk with the mother during the assessment, look to see if the child moves and bends his neck easily as he looks around. If the child is moving and bending his neck, he does not have a stiff neck.

If you did not see any movement, or if you are not sure, draw the child’s attention to his umbilicus or toes. For example, you can shine a flashlight on his toes or umbilicus or tickle his toes to encourage the child to look down (see Figure 6.1). Look to see if the child can bend his neck when he looks down at his umbilicus or toes.

If you still have not seen the child bend his neck himself, ask the mother to help you lie the child on his back. Lean over the child; gently support his back and shoulders with one hand. With the other hand, hold his head. Then carefully bend the head forward toward his chest (see Figure 6.2). If the neck bends easily, the child does not have a stiff neck. If the neck feels stiff and there is resistance to bending, the child has a stiff neck. Often a child with a stiff neck will cry when you try to bend his neck.

LOOK or FEEL for bulging fontanelle (age less than 12 months)

Hold the infant in an upright position. The infant must not be crying. Then look at and feel the fontanelle. The fontanelle is the soft (not hard or bony) part of the head normally found in infants. If the fontanelle is bulging rather than flat, this may mean the young infant has meningitis.

LOOK for runny nose

A runny nose in a child with fever may mean that the child has a common cold. When malaria risk is low, a child with fever and a runny nose does not need antimalarial drugs. The fever is probably due to the common cold.

6.2.3 Assessing measles

Assess a child with fever to see if there are signs suggesting measles. Look for a generalised rash and for one of the following signs: cough, runny nose or red eyes.

Generalised rash

In measles, a red rash begins behind the ears and on the neck. It spreads to the face first and then over the next 24 hours, the rash spreads to the rest of the body, arms and legs. After four to five days, the rash starts to fade and the skin may peel.

Measles rash does not have blisters or pustules. The rash does not itch. You should not confuse measles with other common childhood rashes such as chicken pox, scabies or heat rash. Chicken pox rash is a generalised rash with vesicles (raised, fluid-filled spots). Scabies occurs on the hands, feet, ankles, elbows and buttocks, and is itchy. Heat rash can be a generalised rash with small bumps and is also itchy. A child with heat rash is not sick. You can recognise measles more easily during times when other cases of measles are occurring in your community.

Cough, runny nose or red eyes

To classify a child as having measles, the child with fever must have a generalised rash and one of the following signs: cough, runny nose or red eyes.

If the child has measles now or within the last three months:

LOOK to see if the child has mouth or eye complications

You have already looked at how to assess other complications of measles, such as stridor in a calm child, pneumonia and diarrhoea, in earlier study sessions in this Module. You will learn about other complication such as malnutrition and ear infection in later study sessions.

LOOK for mouth ulcers. Are they deep and extensive?

Mouth ulcers are common complications of measles which interfere with the feeding of a sick child. Look for mouth ulcers in every child with measles and determine whether they are deep and extensive.

The mouth ulcers should be distinguished from Koplik spots. Koplik spots occur inside the cheek during the early stages of measles infection. They are small irregular bright spots with a white centre. They do not interfere with feeding.

LOOK for pus draining from the eye

Pus draining from the eye is a sign of conjunctivitis. If you do not see pus draining from the eye, look for pus on the eyelids.

Often the pus forms a crust when the child is sleeping and seals the eye shut. It can be gently opened with clean hands. Wash your hands before and after examining the eye of any child with pus draining from the eye.

LOOK for clouding of the cornea

The cornea is the transparent covering of the front part of the eye.

Look carefully for corneal clouding in every child with measles. The corneal clouding may be due to vitamin A deficiency which has been made worse by measles. If the corneal clouding is not treated, the cornea can ulcerate and cause blindness.

A child with clouding of the cornea needs urgent referral and treatment with vitamin A.

What kinds of complications might a child have who had measles a month ago?

If a child has had measles at any time in the past three months you should check to see if he has any mouth complications such as ulcers, which interfere with feeding if they are deep and extensive. You should also look to see if the child has eye problems such as conjunctivitis or corneal clouding which can ulcerate and cause blindness.

6.3 Classifying fever

The next step after assessing for fever and measles is to classify the illness. If the child has fever and no signs of measles, classify the child for fever only. If the child has signs of both fever and measles, classify the child for both.

Activity 6.1 Assess and classify fever (1)

This activity will help you to check your understanding of what you have learned so far. Make notes in your Study Diary in answer to the following questions:

- a.How would you classify a child with fever who lives in a low risk malaria area, and who does not have measles or a runny nose?

- b.If a child brought to your health post with fever has recently travelled to another area, but neither his mother nor you know the malaria risk for that area, how would you classify the child?

- c.What is the classification in all cases when a child has a fever and a stiff neck, bulging fontanelle or any general danger sign?

Comment

As you may recall, the Assess and Classify chart has three tables for fever classification. One is for classifying fever when the risk of malaria is high; the second is for when the risk of malaria is low and the third is for classifying fever when there is no malaria risk.

Therefore, to classify fever, you must know if the malaria risk is high, low or none and then select the appropriate table.

For the child in question (a) above, you would use the ‘low risk’ table and classify for ‘malaria low risk’.

![]() All children with fever and a stiff neck, bulging fontanelle or any general danger sign must be referred urgently.

All children with fever and a stiff neck, bulging fontanelle or any general danger sign must be referred urgently.

The child in question (b) will need to be classified according to the high risk malaria table. You read that if you do not know the risk of malaria in an area a child has visited, you should assume ‘high risk’. Therefore this child should be classified as ‘malaria high risk’.

(c) In all cases where a child with fever also has a stiff neck, bulging fontanelle or any general danger sign, they must be classified as very severe febrile disease. In such cases you must refer the child urgently.

You will now look in more detail at how to classify malaria.

6.3.1 Classification of malaria

High malaria risk

There are two possible classifications of fever when the malaria risk is high:

- Very severe febrile disease

- Malaria.

When the risk of malaria is high, the chance is also high that the child's fever is due to malaria.

If the child with fever has any general danger sign or a stiff neck, classify the child as having very severe febrile disease (High Malaria Risk).

If a general danger sign or stiff neck is not present but the child has fever (by history, feels hot, or temperature 37.5°C or above) in a high malaria risk area, you should classify the child as having malaria (High Malaria Risk).

Low malaria risk

If you see children for whom the risk of malaria is low, use the Low Malaria Risk classification table. There are three possible classifications of fever in a child with low malaria risk:

- Very severe febrile disease

- Malaria

- Fever – malaria unlikely.

If the child has any general danger sign or a stiff neck, and the malaria risk is low, classify the child as having very severe febrile disease (Low Malaria Risk).

If the child does not have signs of very severe febrile disease and the risk of malaria is low, a child with fever and no runny nose, no measles and no other cause of fever is classified as having malaria (Low Malaria Risk).

When signs of another infection are not present, and blood film and rapid diagnostic test (RDT) for malaria are not available, you should classify and treat the illness as malaria even though the malaria risk is low.

If the child does not have signs of very severe febrile disease or of malaria and the malaria risk is low and the child has a runny nose, measles or other cause of fever, classify the child as having fever – malaria unlikely.

No malaria risk

There are two possible classifications of fever in a child with no malaria risk:

- Very severe febrile disease

- Fever – no malaria.

If the child has any general danger sign or a stiff neck, and there is no malaria risk, classify the child as having very severe febrile disease (No Malaria Risk).

![]() A child with any general danger sign, stiff neck or bulging fontanelle should be classified as very severe febrile disease and referred urgently.

A child with any general danger sign, stiff neck or bulging fontanelle should be classified as very severe febrile disease and referred urgently.

When there is no malaria risk, a child with fever who has not travelled to a malarious area should be classified as fever — no malaria.

6.4 Treatment for fever and malaria

The treatment for fever or malaria is not based on classification of malaria risk. Therefore once you have classified for fever, the treatment is the same. The exception is where there is no malaria risk when you do not have to treat the child with an antimalarial drug.

Treatment for malaria is described in detail in Study Session 8 of Communicable Diseases, Part 1. All the drugs and dosages are listed there, including for children aged over 4 months, and adults.

6.4.1 Very severe febrile disease or severe malaria

A child with fever and any general danger sign or stiff neck may have meningitis, severe malaria (including cerebral malaria) or sepsis. It is not possible to distinguish between these severe diseases without laboratory tests.

A child classified as having very severe febrile disease needs urgent treatment and referral. Before referring urgently, you should give a dose of paracetamol if the child’s temperature is 38.5°C or above, and prevent low sugar by ensuring the child has food on the journey to hospital. You should administer artesunate rectally as indicated in Table 6.1 below.

| Weight (kg) | Age | Artesunate dose (mg) | Regimen (single dose) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5–8.9 | 0–12 months | 50 | One 50 mg suppository |

| 9–19 | 13–41 months | 100 | One 100 mg suppository |

| 20–29 | 42–60 months | 200 | Two 100 mg suppositories |

6.4.2 Malaria

Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax are the commonest species of malaria parasite in Ethiopia.

Treat a child over 4 months of age, classified as having P. falciparum malaria, with Coartem (or chloroquine if RDT confirms P. vivax malaria). You should give paracetamol if the child has a fever. If the fever has been present every day for more than seven days, you should refer the child for assessment.

6.4.3 Fever (no malaria)

If the child’s fever is high, give paracetamol. Advise the mother to return for a follow-up visit in two days if the child’s fever persists. If the fever has been present every day for more than seven days, then you should refer the child for assessment.

6.4.4 Follow-up care and treatment for fever or malaria

The follow-up care for high and low risk malaria is set out in Box 6.4. If the child’s fever persists after two days, or returns within 14 days of the initial classification, you should do a full re-assessment of the child. You should consider whether there are other causes of the fever.

Box 6.4 Follow-up care for malaria (low or high risk)

If the fever persists after two days, or returns within 14 days:

- Do a full reassessment of the child.

- Use the Assess and Classify chart.

- Assess for other causes of fever.

Treatment

- If the child has any general danger sign or a stiff neck, treat as very severe febrile disease.

- Ask if the child has actually been taking his antimalarial drugs. If he hasn’t, make sure that he takes it.

- If the child has any cause of fever other than malaria, provide treatment.

- If malaria is the only apparent cause of fever, refer the child to hospital.

6.5 Classifying measles

A child with fever and who has measles, or has had measles within the last three months, should be classified both for fever and for measles.

There are three possible classifications of measles:

- Severe complicated measles

- Measles with eye or mouth complications

- Measles.

6.5.1 Severe complicated measles

Children with measles may have other serious complications. A child with any general danger sign, clouding of the cornea or deep and extensive mouth ulcers will be classified as ‘severe complicated measles’.

6.5.2 Measles with eye or mouth complications

If the child has pus draining from the eye or mouth ulcers which are not deep or extensive, you should classify the child as having measles with eye or mouth complications. A child with this classification does not need referral.

6.5.3 Measles

All children with measles should receive a therapeutic dose of vitamin A.

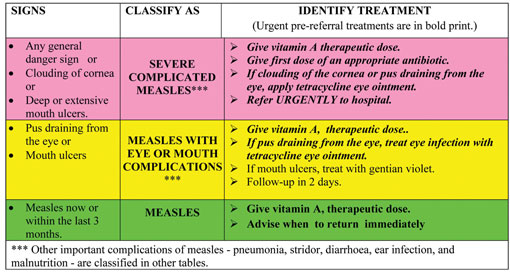

A child with measles now or within the last three months and with none of the complications listed in the pink or yellow rows is classified as having measles. You should give the child a therapeutic dose of vitamin A to help prevent measles complications from developing. Table 6.2 summarises these classifications and also indicates what treatment should be provided according to the classification.

Table 6.2 Assess and classify table for measles.

You are now going to look at how you treat measles and associated complications.

6.6 Treatment of measles

6.6.1 Severe complicated measles

All children with severe complicated measles should receive urgent treatment and referral. Give the first dose of vitamin A to the child and an appropriate antibiotic and then refer the child urgently. If there is clouding of the cornea, or pus draining from the eye, apply eye ointment.

6.6.2 Measles with eye or mouth complications

Identifying and treating measles complications in infants and children in the early stages of the infection can prevent many deaths. As you read earlier, these children should be treated with vitamin A. It will help decrease the severity of the complications as well as correct any vitamin A deficiency. The mother should be taught how to treat the child’s eye infection or mouth ulcers at home.

Eye infections should be treated as follows:

- If pus is still draining from the eye, ask the mother to describe how she has treated the eye infection. If treatment has been given correctly, you should refer the child to hospital. If not, teach the mother the correct treatment; this may help to solve the problem.

- If the pus is gone but redness remains, tell the mother to continue the treatment.

- If no pus or redness, tell the mother she can stop the treatment.

Mouth ulcers should be treated with gentian violet twice daily as follows:

- Wash hands.

- Clean the child’s mouth with a clean soft cloth wrapped around a clean stick or the end of a spoon and wet with salt water.

- Paint the mouth with half strength gentian violet.

- Wash hands again.

Treating mouth ulcers helps the child to resume normal feeding more quickly.

6.6.3 Follow-up care for measles with eye or mouth complications

You should give follow-up care to the child after two days: you should look for red eyes and/or pus draining from the eyes and you should check to see whether the child still has the mouth ulcers. If the child’s mouth ulcers are worse, or there is a very foul smell from the mouth, you should refer the child to hospital. If the mouth ulcers are the same or better, you should tell the mother that she must continue to use the gentian violet for a total of five days.

You are now going to do a short activity which will help you to understand the main points that you have covered in this study session.

Activity 6.2 Assess and classify fever (2)

Read Case Study 6.1 and then answer the questions below. You should either have a copy of the Assess and Classify chart to help you with this activity, or you could refer to the sections from the chart that are reproduced in this study session.

Case Study 6.1 Pawlos’s story

Pawlos is ten-months-old. He weighs 8.2 kg. His temperature is 37.5°C. His mother says he has a rash and cough.

The health worker checked Pawlos for general danger signs. Pawlos was able to drink, was not vomiting, did not have convulsions and was not lethargic or unconscious.

The health worker next asked about Pawlos’s cough. The mother said Pawlos had been coughing for five days. The health worker counted 43 breaths per minute. She did not see chest in-drawing nor hear stridor. Pawlos did not have diarrhoea.

The mother said Pawlos had felt hot for two days and that they lived in a high malaria risk area. Pawlos did not have a stiff neck. He has had a runny nose with this illness.

Pawlos had a rash covering his whole body. Pawlos’s eyes were red. The health worker checked the child for complications of measles. There were no mouth ulcers. There was no pus draining from the eye and no clouding of the cornea.

- a.Does Pawlos have severe febrile disease? Write down your reasons for your answer.

- b.What malaria classification would you record on Pawlos’s form and why?

- c.How would you classify Pawlos’s measles? Write down reasons for your answer.

Comment

To help you understand the process of classification for Pawlos, we have set out below how the health worker classified Pawlos’s fever, using the table for classifying fever when there is a high malaria risk. (If you have your chart booklet with you, you should open it on page 24.)

- a.First, the health worker checked to see if Pawlos had any of the signs in the pink row. She thought, ‘Does Pawlos have any general danger signs or a stiff neck? No, he does not. Pawlos does not have any signs of severe febrile disease.’

- b.Next, the health worker looked at the yellow row. She thought, ‘Pawlos has a fever. His temperature measures 37.5°C. He also has a history of fever because his mother says Pawlos felt hot for two days. He is from a high malaria risk area’. She classified Pawlos as having malaria.

- c.Because Pawlos had a generalised rash and red eyes, Pawlos has signs suggesting measles. To classify Pawlos’s measles, the health worker looked at the classification table for classifying measles.

- She checked to see if Pawlos had any of the signs in the pink row. She thought, ‘Pawlos does not have any general danger signs. The child does not have clouding of the cornea. There are no deep or extensive mouth ulcers. Pawlos does not have severe complicated measles.’

- Next the health worker looked at the yellow row. She thought, ‘Does Pawlos have any signs in the yellow row? He does not have pus draining from the eye. There are no mouth ulcers. Pawlos does not have measles with eye or mouth complications.’

- Finally the health worker looked at the green row. Pawlos has measles, but he has no signs in the pink or yellow row. The health worker classified Pawlos as having measles.

In this study session you have learned about assessing fever in children. As you read earlier, fever may be caused by a serious illness such as malaria, measles or meningitis, and therefore it is critical that you are able to classify these conditions and ensure the sick child receives the correct treatment as quickly as possible.

Summary of Study Session 6

In Study Session 6, you have learned that:

- Fever is a symptom of both simple and serious diseases.

- Identifying serious disease is very important to prevent death among children.

- To assess for fever you need to determine the malaria risk, ask about the duration of any fever, ask about and look for measles, look and check for signs of meningitis.

- Malaria, measles and other severe febrile diseases like meningitis should be classified to give appropriate and prompt treatment.

- Infants and children with severe febrile diseases and severe complicated measles should be referred urgently.

- Malaria and measles with eye or mouth complications can be treated at the health post, while measles and fever with no malaria can be treated at home.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 6

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 6.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 6.1 and 6.2)

If a child is brought to the health post with a fever, what would you need to do immediately and why?

Answer

You need to decide the cause of the fever: whether it is due to malaria, meningitis, measles, or another cause. This is because the treatment you give in each case will be different and may involve urgent referral.

Read Case Study 6.2 and then answer the questions below.

Case Study 6.2 for SAQ 6.2

Abdi is three years old. He weighs 9.4 kg. He feels hot and has also had a cough for three days. Abdi is able to drink, has not vomited, has not had convulsions, and has not been lethargic or unconscious during the visit to the health post. His breathing rate is 51 a minute. The health worker did not see chest in-drawing or hear stridor when he is calm. Abdi does not have diarrhoea.

The mother says Abdi has felt hot for five days. The risk of malaria is high.

Abdi has not had measles within the last three months. He does not have a stiff neck; there is no runny nose, and no generalised rash.

SAQ 6.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 6.2 and 6.3)

- a.What are the child’s signs?

- b.How would you classify his illness?

Answer

- a.You should have noted that the signs present in Abdi’s case are: fever, cough and fast breathing.

- b.Therefore you should have classified his illness as pneumonia because he has cough and fast breathing. And malaria because he has fever and he is living in a high risk malaria area.

Read Case Study 6.3 and answer the questions below.

Case Study 6.3 for SAQ 6.3

Lemlen is three years old. She weighs 10 kg. Her temperature is 38°C. She has been coughing for two days, has a generalised rash and has felt hot for three days. She is able to drink, has not been vomiting and does not have convulsions. She is not lethargic. The health worker counts 42 breaths per minute. There is no chest in-drawing or stridor when she is calm. She has no diarrhoea. She does not have a stiff neck or runny nose, or mouth ulcers or pus draining from the eye. There is no clouding of the cornea.

SAQ 6.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 6.1, 6.2, 6.3 and 6.4)

- a.How would you classify Lemlen’s illness?

- b.How would you treat her illness?

Answer

- a.You should have classified Lemlem’s illness as pneumonia because she has a cough and fast breathing; and measles because she has fever, generalised rash and red eyes.

- b.The treatment for Lemlen is:

- Cotrimoxazole: one adult tablet or three paediatric tablets or 7.5 ml syrup twice daily for five days

- Vitamin A: give 200,000 IU on Day 1, repeat same dose on Day 2 and Day 15

- Paracetamol: one tablet of 500 mg every six hours for reducing the fever.