Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 8 March 2026, 6:28 AM

Labour Delivery and Care Module: 3. Care of the Woman in Labour

Study Session

Introduction

In the previous session of this Module you were introduced to the definitions, signs and symptoms, and stages of normal labour. Labour and birth of the baby is a unique experience in the life of any family and one of special personal significance for the mother. Your constant companionship and skilful management of the birth can contribute much to the harmonious atmosphere and feeling of trust during labour and delivery, which favours a good outcome. Caring for the woman in labour demands sensitivity from you as the birth attendant, and awareness of the mother’s perception of her labour and of her needs, as they relate to her experience.

In this session you will learn about ways that you can support a woman all through the birth of the baby. You will also be introduced to the basic principles of maternal and fetal monitoring during labour, and learn about standard hygiene for infection prevention and the equipment you need to prepare for a delivery at home or in a health facility.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 3

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

3.1 Define and use correctly all of the key terms printed in bold. (SAQ 3.7)

3.2 Assess the individual needs of the woman in labour and provide care accordingly. (SAQs 3.1 and 3.7)

3.3 Provide emotional and psychological support for the woman in labour. (SAQ 3.1)

3.4 Perform proper maternal and fetal monitoring and recording in the first and second stages of labour. (SAQs 3.2, 3.3, 3.5 and 3.6)

3.5 Prepare delivery equipment for a normal birth. (SAQ 3.4)

3.6 Adopt standard hygiene precautions and infection prevention in delivery care. (SAQs 3.4 and 3.7)

3.1 Assessing the needs of the woman in labour

Every woman needs a different kind of support. But all women need kindness, respect and attention. Watch and listen to her to see how she is feeling. Encourage her, so she can feel strong and confident in labour. Help her relax and welcome her labour.

3.1.1 Support the labour

When you support the mother’s labour, you help her relax instead of fighting against it (Figure 3.1). Although labour support will not make labour painless, it can make labour easier, shorter and safer. You will learn many ways to support the labour in this study session, including by physical actions (touch, sounds, etc.) and giving psychological and emotional support.

3.1.2 Guard the labour

When you guard the labour, you protect it from interference.

Keep rude and unkind people away. The mother should not have to worry about family problems. Sometimes even supportive and loving friends can interfere with the labour. At some births, the best way to help is to ask everyone to leave the room so that the mother can labour without being distracted.

![]() Do not use unnecessary drugs or procedures! Do not give the mother drugs to hurry the labour — they add useless risks.

Do not use unnecessary drugs or procedures! Do not give the mother drugs to hurry the labour — they add useless risks.

Some people believe that more drugs, tools and examination of the mother will make the birth safer. But that is usually not true — they can make the birth harder or cause problems. Injections or pills that are supposed to hurry the birth can make labour more painful, and can kill both the mother and the baby.

3.1.3 Position and mobility

Several considerations govern the choice of position during the first stage of labour. Of these the most important is that of maternal preference — how she prefers to give birth. But some women need your encouragement to try different positions.

Help the woman move during labour. She can squat, sit, kneel or take other positions (Figure 3.2). All of these positions are good. Changing positions helps the cervix open more evenly.

3.1.4 Helping the mother to manage her contractions

In early labour she may be able to sleep. Many women feel very tired when their contractions are strong. They may fear they will not have the strength to push the baby out. But feeling tired is the body’s way of making the mother rest and relax. If everything is all right, she will have the strength to give birth when the time comes.

To save her strength, the mother should rest between contractions, even when labour first begins. This means that when she is not having a contraction, she should let her body relax, take deep breaths, and sometimes sit or lie down.

3.1.5 Touch

![]() Do not massage the belly. It will not speed labour and can cause the placenta to separate too soon. (You already learned about premature separation of the placenta and late pregnancy bleeding in Study Session 21 of the Antenatal Care Module, Part 2. It can also happen too soon during labour.)

Do not massage the belly. It will not speed labour and can cause the placenta to separate too soon. (You already learned about premature separation of the placenta and late pregnancy bleeding in Study Session 21 of the Antenatal Care Module, Part 2. It can also happen too soon during labour.)

Labour can be more difficult when the woman is afraid or tense. Reassuring the woman that the pain she has is normal can help lessen that fear. Touch can help a woman in labour, but find out what kind of touch she wants. Here are some examples of touch that women often like:

- A firm, still hand pressing on the lower back during contractions

- Massage between contractions, especially on the feet or back

- Hot or cold cloths on the lower back or belly (Figure 3.3). If the mother is sweating, a cool wet cloth on the forehead usually feels good.

3.1.6 Sounds

Making sounds in labour can help women to allow the birth canal to open. Not all women want to make noise, but encourage women to try. Low sounds, like growling animal noises or humming, can be very helpful. Some women chant or sing. The woman can be as loud as she wants to be.

Some noises can make women feel more tense. High-pitched sounds and screams usually do not help. If she starts to make high, tense sounds, ask her to make low sounds (Figure 3.4).

3.1.7 Breathing

The way a woman breathes can have a strong effect on how her labour will feel. In the first stage of labour, there are many kinds of breathing that may make labour easier. Try these ways of breathing yourself and show the mother how to do it. Help her to choose which one works best to minimise the pain. Encourage mothers to try different ways of breathing throughout labour:

- Slow blowing. Ask the woman to take a long, slow breath. To breathe out she should make a kiss with her lips and slowly blow. Breathing in through the nose can help her breathe slowly.

- Hee breathing. The woman takes a slow deep breath and then blows out short, quick breaths while she makes soft ‘hee, hee’ sounds.

- Panting. The woman takes quick, shallow breaths.

- Strong blowing. The woman blows hard and fast.

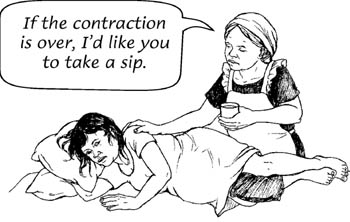

3.1.8 Drinking fluids during labour

A woman in labour uses up the water in her body quickly and she also uses up a lot of energy. During the first stage of labour, she should drink at least 1 cup every hour of a high calorie fluid such as tea, soft drinks, soup, or fruit juice. If she does not drink enough, she may get dehydrated (not enough water in the body). This can make her labour much longer and harder. Dehydration can also make a woman feel exhausted.

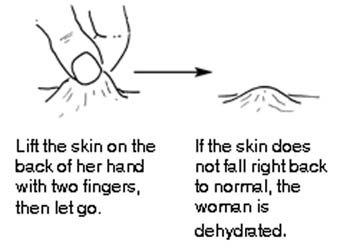

Signs of dehydration include:

- Dry lips

- Sunken eyes

- Loss of stretchiness of skin

- Mild fever (up to 38°C)

- Fast, deep breathing (more than 20 breaths a minute)

- Fast, weak pulse (more than 100 beats a minute)

- Baby’s heartbeat faster than 160 beats a minute.

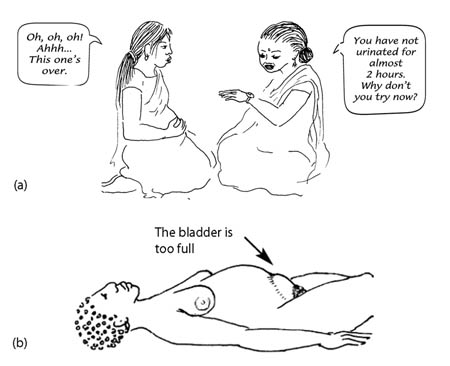

3.1.9 Bladder care

Encourage the woman to urinate at least once every 2 hours (Figure 3.5a). If her bladder is full, her contractions may get weaker and her labour longer. A full bladder can also cause pain, problems with pushing out the placenta, and bleeding after childbirth. Remind the mother to urinate – she may not remember.

To check if the bladder is full, feel the mother’s lower belly. A full bladder feels like a plastic bag full of water. When the bladder is very full, you can see the shape of it under the mother’s skin (Figure 3.5b). Do not wait until her bladder gets this big.

If the mother’s bladder is full, she must urinate. If she cannot walk, try putting a pan or extra padding under her bottom and let her urinate where she is. It may help her to begin to urinate if you dip her hand in warm water.

Why do you think a full bladder can interfere with the normal progress of labour? (Think back to what you know from the previous two study sessions.)

During the first and second stage of labour, a full bladder interferes with the normal uterine contraction and inhibits the baby’s head from entering the pelvic brim.

As you will see in Study Session 6, during the third stage of labour it can also delay delivery of the placenta, which increases the risk of post-partum haemorrhage (Study Session 11).

3.1.10 Emotional and psychological support for the woman in labour

Emotional and psychological support for the woman in labour consists of helping the mother to feel in control of herself, to feel accepted whatever her reactions and behaviour may be and to complete her labour feeling that she is a success, even if the outcome was not what she hoped for. There are several ways you can help her to achieve this.

Companion in labour

You do not have to work alone to give support to the mother during labour. There is evidence that the presence of constant support from the woman’s husband, close relatives or friends in labour favours good progress. There is no rule about who should support her if they care about her and are willing to help her. Most important, they should be people the mother wants to have at the birth.

Good communication

Keep the woman informed about the progress of labour. The woman has the right to know about the progress of labour and the condition of herself and the baby. Counsel the woman and her support person about ongoing care such as physical care, comfort and emotional support.

Counsel the woman (and her support person) what to expect early in labour, before contractions become too painful, and later when contractions become stronger (where feasible). Explain about the contractions getting stronger and closer together as she gets closer to the time to deliver baby. Explain what to expect during the delivery. Reassure the woman that you will be with her throughout the process of giving birth.

3.2 Maternal and fetal monitoring during labour

Proper maternal and fetal monitoring during labour is very important as this is the only way to assess the progress of labour and to identify deviations from normal.

3.2.1 Assessing the progress of labour

Labours are all different. Some are fast, some are slow. This is normal. But in a healthy labour, there should be progress. Progress means that labour should be getting stronger and the cervix should be opening. Box 3.1 summarises the main features of a labour that is progressing normally.

Box 3.1 Gradual progress of normal labour

- Contractions get longer, stronger and closer together.

- The uterus feels harder when you touch it during a contraction (Figure 3.6).

- Amount of ‘show’ increases.

- The bag of waters breaks.

- The mother burps, sweats and vomits, or her legs shake.

- The mother feels she wants to push down through her lower abdomen.

In Study Session 4 you will learn how to use a chart called a partograph to assess the progress of labour and record your observations and measurements accurately. But first we are going to describe what happens in the woman’s body to introduce you to the important features that need to be assessed during labour.

3.2.2 Uterine contractions

The frequency, length and strength of the contractions should be monitored and recorded every half hour. Frequency indicates the number of contractions the woman has in ten minutes. Count them. Length refers to the amount of time each contraction lasts. Measure the time on your watch (if you have one). Strength indicates the severity of pain experienced during each contraction; ask the mother to tell you about this.

In normal labour, as the labour progresses the contractions become more frequent, they last longer, and they feel stronger to the mother (more painful).

3.2.3 Dilatation of the cervix

The progress of labour is usually assessed by the degree of dilatation of the cervix. Cervical dilatation is assessed by doing a vaginal examination every four hours and using your fingers to estimate how wide the cervix has opened. (We described how to do this in Study Session 2). In normal labour the average rate for cervical dilatation is one centimetre every hour (1 cm per hour).

3.2.4 Descent of the presenting part

You measure descent of the presenting part of the fetus by abdominal palpation in relation to the pelvic brim. The descent of the presenting part can also be detected by vaginal examination. This should be assessed and recorded every two hours during the labour.

3.2.5 Discharges from the vagina

Show is the name given to the blood-stained mucus seen in early labour. Towards the end of the first stage a trickle of blood may appear. Amniotic fluid may be seen trickling from the vagina after the membranes have ruptured. The presence of mechonium (mechonium is pronounced ‘mee-koh-nee-um’). Mechonium (dark-green coloured discharge, which is the first stool of the baby) in the amniotic fluid suggests fetal distress as it does not normally pass stool until after the birth. Later in this Module, you will learn what actions to take if the fetus or the mother is endangered.

3.2.6 Fetal condition

The fetal condition during labour can be assessed by obtaining information about the fetal heart rate (the number of beats per minute) and its pattern in relation to the mother’s contractions. Check the fetal heart rate every 30 minutes by listening (auscultation), which you learned to do in Study Session 11 of the Antenatal Care Module using a fetoscope or stethoscope.

Do you remember what is the normal range of the fetal heart rate?

Normal fetal heart rate ranges from 100–180 beats per minute.

3.2.7 Maternal condition

Count the woman’s pulse rate every 30 minutes and measure her blood pressure and temperature every four hours, as you learned how to do in Study Session 9 of the Antenatal Care Module. Additionally, document on your labour monitoring chart how often the mother eats, drinks and urinates.

Blood pressure goes down

![]() If the woman’s blood pressure suddenly drops, she needs to go to the hospital immediately!

If the woman’s blood pressure suddenly drops, she needs to go to the hospital immediately!

If her diastolic blood pressure (the bottom number) suddenly drops 15 points or more, this is a dangerous warning sign. This usually means that the mother is bleeding heavily. If you do not see any bleeding from her vagina, her placenta may have detached and she might have bleeding inside (intrapartum haemorrhage).

Blood pressure goes up

Blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg or higher is a warning sign. The woman may have pre-eclampsia, which can cause convulsions (eclampsia), detached placenta, bleeding in the brain, or a severe haemorrhage. The baby may die and the mother may die as well. You learned all about eclampsia and pre-eclampsia in Study Session 19 of the Antenatal Care Module, Part 2. Blood pressure and all the other measurements outlined above are recorded on the partograph, as you will learn in the next study session.

Next we turn to the equipment you will need to prepare for the delivery.

3.3 Preparing to conduct a delivery

When the woman is approaching the second stage of labour you should prepare for the delivery of the baby.

3.3.1 Signs of second stage labour

- Contractions becomes stronger and more expulsive.

- Dilation and ‘gapping’ of the anus (the anal sphincter opens during the contraction).

- Appearance of the presenting part of the fetus under the vulva.

- Full dilation of the cervix to a diameter of 10 cm.

3.3.2 Preparing the birthing place

Once the onset of the second stage has been confirmed you should make preliminary preparations for the delivery. The room should be warm and well lit so that the perineum and vulva can be easily observed. A clean surface should be prepared to receive the baby (Figure 3.7) using the infection control procedures described in Section 3.5. Spread waterproof covers to protect the bed and the floor. Make sure there is a warm coat and clothes for the baby.

3.3.3 Equipment and supplies needed to conduct delivery

You should always have all the supplies and tools you will need for the birth (Box 3.2 and Figure 3.8) ready at the Health Post and you should take them to the woman’s home if the delivery is going to happen there. She may be able to provide some of the simplest things, like soap and clean cloths, but you should always be fully prepared. Use Box 3.2 as a checklist — tick each item as you pack it to go to a birth.

Box 3.2 Checklist of birthing equipment

- Clean water, soap and hand towel.

- Apron, goggle, face mask and gown.

- Sterile gloves.

- Sterile or very clean new string to tie the cord.

- New razor blade or sterilised scissors.

- Two sterile clamp forceps, for clamping the umbilical cord before you cut it.

- Mucus trap or suction bulb to suck mucus from the baby’s airways (if needed).

- Sterile gauze, cotton swab and sanitary pad for the mother.

- Two dry, clean baby towels and two drapes.

- Blood pressure cuff and stethoscope.

- Antiseptic solution for cleaning the mother’s perineum and genital area.

- 10 IU (international units) of the injectable drug called oxytocin, or 600 µg (microgram) tablets of misoprostol. These drugs are used for the prevention of post-partum haemorrhage. Oxytocin is the preferred drug for this purpose, but if you don’t have it then misoprostol can be used. (You will learn all about this in Study Session 6.)

- Tetracycline eye ointment (antibiotic eye ointment used for the prevention of eye infection in the newborn; you will learn about this in the next Module, on Postnatal Care).

- Three buckets or small bowls each with 0.5% chlorine solution, or soap solution and clean water. (To prepare 0.5% chlorine solution you can use the locally available Berekina. Read the concentration from the bottle — if it is 5% you can make a solution of 0.5% strength by mixing one cup of Berekina with nine cups of clean water.)

- Plastic bowl to receive the placenta.

3.4 Preventing infection during delivery

Infection makes people sick and can even kill them. It is one of the most common causes of death after childbirth. Most of your actions during labour and delivery can be safe only if you are able to follow the basic rules to prevent infection, as outlined in this section. You can summarise these rules as the ‘three cleans’: clean hands, clean surface (for the delivery) and clean equipment. You already know you must thoroughly clean the place where the baby will be born. In addition, you should follow other standard hygiene measures as described below.

3.4.1 Handwashing

How can you prevent infection by washing your hands?

Washing your hands is one of the most important things you can do to prevent infection. It prevents you from spreading germs to another person, and it helps protect you from germs, too.

If you can do nothing else to prevent infection, you must wash your hands (see Figure 3.9 and Box 3.3).

Box 3.3 Always do a 2-minute handwash

| Before you | After you |

|---|---|

Touch the mother’s vagina | Clean up after the birth |

Do a vaginal or pelvic examination | Touch any blood or other body fluids |

Deliver the baby | Urinate or pass stool |

Check the newborn |

Alcohol and glycerine hand cleaner

You can make a simple hand cleaner (rub) to use if you do not have water to wash your hands. When used correctly, this cleaner will kill most of the germs on your hands.

Mix 2 ml (millilitres) of glycerine with 100 ml of ethyl or isopropyl alcohol (strength 60% to 90%) or any alcohol used for skin cleaning before an injection.

To clean your hands, rub about 5 ml (1 teaspoon) of the hand cleaner into your hands, rub them together thoroughly and make sure to clean between your fingers and under your nails. Keep rubbing until your hands are dry. Do not rinse your hands or wipe them with a cloth.

Wash your hands with soap and water after every 5–10 uses of the hand cleaner solution to reduce the build-up of hand softeners.

Do not use a hand rub if your hands are contaminated with body fluids or are visibly dirty; instead wash your hands with soap and water.

3.4.2 Wear protective clothing

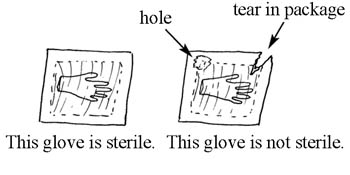

Gloves

There are different kinds of gloves for different purposes. Utility or heavy duty gloves are used for touching dirty instruments, linens and waste; doing housekeeping; and cleaning contaminated surfaces. Sterile, single-use clean examination gloves are used when you will come into contact with unbroken mucus membranes (when you are doing a vaginal examination), or when you are at risk of exposure to blood or other body fluids. Sterile (germ-free) surgical gloves are used for all procedures having contact with tissues under the skin or with the bloodstream.

Wear gloves whenever you touch the mother’s genitals, or any blood or body fluid. After use, discard the gloves safely.

Face mask, eye protection and apron or gown

A face mask, eye protection and a very clean apron or gown are worn for sorting and cleaning instruments and linens, attending a vaginal delivery, and cutting the umbilical cord. Eye protection can include goggles, face shields or plain glasses.

Feet protection

Feet protection should be a closed shoe or boot made from rubber or leather. If leather, cover the shoes with plastic bags. Shoes or boots protect the wearer from injury by sharp or heavy items, and the plastic bags protect you from blood or other body fluids on the floor.

3.4.3 Clean and high-level disinfect your tools

Before and after the baby has been born, decontaminate (remove germs) from all instruments with a 0.5% chlorine solution. First, soak them for 10 minutes, then wash with a soapy solution and lastly with clean water. You can use a small brush to scrub them clean. After decontamination make the instruments sterile (germ-free) by using a steriliser machine, or boil them for 20 minutes. (If you have access to a steriliser machine, follow the instructions carefully.)

3.4.4 Clean surface for delivery and safe disposal of birth wastes

Make sure the area where the mother will give birth is scrubbed clean, and that all cloths, towels or drapes are clean and dry — particularly those the mother lies on and the cloths you wrap around the newborn baby to clean it.

Put all wastes after the birth (blood, contaminated cloths, membranes and the placenta) in a leak-proof container such as a tin with a tight-fitting lid, and dispose of it safely in a proper place where it is unlikely to be found. It is usually recommended to bury wastes in the ground or burn them. It is very important to prevent other people in the community from getting sick from the germs left on these wastes.

Be careful with needles. When you have finished using a disposable syringe, put the needle into the safety box. Do not leave needles lying around.

3.5 In conclusion

Now that you know how to support the woman in labour, what equipment is needed and how to dispose of wastes, we can progress to teaching you about the delivery itself. In the next study session you will learn how to use the partograph.

Summary of Study Session 3

In Study Session 3 you have learned that:

- All women during labour and delivery need individualised care. Pregnant women should be encouraged to seek support from a skilled birth attendant.

- Provide physical and psychological support to the woman in labour and the trusted support person who is with her.

- Assist her to adopt different positions, try different breathing patterns, be massaged on her back and make low sounds during labour, as this helps her to relieve pain and manage the contractions.

- Encourage her to take one cup of fluid at least every hour and assist her to empty her bladder at least once every two hours.

- Keep her informed about the progress of her labour, so she remains relaxed and confident.

- Monitor fetal condition by checking the fetal heart beat every 30 minutes; it should be within the normal range.

- Monitor maternal condition by measuring her blood pressure and temperature every 4 hours, and her pulse rate every 30 minutes.

- Assess the progress of labour by checking uterine contractions (length, strength and frequency) every 30 minutes, descent of the head every two hours and cervical dilatation every four hours.

- Prepare the equipment you will need for the birth, including protective clothing for yourself; scrub or sterilise everything that will come into contact with tissue or body fluids.

- Hand washing with soap and clean water is the most important way to reduce the risk of infection being passed to the mother and baby during labour and delivery.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 3

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the questions below Case Study 3.1. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

First read Case Study 3.1 and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 3.1 Woizero Almaz

Woizero Almaz is a full term pregnant woman who came to the Health Post with pushing down pain and blood stained vaginal discharge which began five hours earlier. This is her first pregnancy and she is very anxious about it. On examination you found she is in first stage of labour.

SAQ 3.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.2 and 3.3)

What support can you give her to alleviate Woizero Almaz’s fear about her condition?

Answer

To reassure Almaz, be kind and respect her and her culture and norms. Show interest in her. Explain what is happening and how the labour will progress. Encourage her to ask questions and express her ideas and worries. Tell her about the condition of her baby. Allow a trusted support person to be with her. Explain each procedure before you do it.

SAQ 3.2 (tests Learning Outcome 3.4)

What assessment tools and means will you use to assess the progress of Almaz’s labour? How will these assessments help you?

Answer

Measuring Almaz’s blood pressure, temperature and pulse helps you to know about her condition. By checking the fetal heartbeat it is possible to identify the presence of fetal distress. Monitoring the contractions, cervical dilatation and descent of the baby’s head all help to assess the progress of labour. (When you have learned about the partograph in Study Session 4, you will know that it is the best tool to follow the progress of labour and to detect any abnormality on time).

SAQ 3.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.5 and 3.6)

During the first stage of labour, what type of food will you recommend to her? And how often will you try to get her to eat something?

Answer

During the first stage of labour, a high calorie fluid diet is recommended. Some examples are tea, soft drinks, soup, and fruit juice. Almaz should drink at least one cup every hour.

SAQ 3.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.5 and 3.6)

When you are providing care to Almaz during her labour, how do you prevent infection being transmitted to her and her baby?

Answer

Adopt standard precautions and infection prevention procedures during vaginal examinations and conducting the delivery. Wash your hands before and after each procedure for at least 2 minutes, using soap and clean water or an alcohol hand cleaner. Wear clean protective clothing such as an apron, goggles, mask, gloves and shoes. Use safe waste disposal methods (burying or burning). Scrub, decontaminate and sterilise metal or glass instruments using a 0.5% chlorine solution for 10 minutes, then cleaning with soapy water and boiling or using a sterilisation machine.

SAQ 3.5 (tests Learning Outcome 3.4)

What will you assess (and how often) to check whether Almaz’s labour is progressing normally?

Answer

You would measure vital signs in the mother: blood pressure and temperature every 4 hours, pulse every 30 minutes.

You would monitor the frequency, length and strength of her contractions every 30 minutes; in normal labour, as the labour progresses, contractions become faster, stronger and more frequent.

Cervical dilatation is assessed by doing a vaginal examination every 4 hours; in normal labour the average rate for cervical dilatation is at least 1 cm per hour.

You would measure the descent of the presenting part every 2 hours by abdominal palpation of the fetal head in relation to the pelvic brim, or by vaginal examination.

SAQ 3.6 (tests Learning Outcome 3.4)

What would indicate that Almaz’s baby is showing signs of fetal distress?

Answer

The presence of dark-green meconium in the amniotic fluid leaking from Almaz’s vagina during labour suggests fetal distress; meconium is the baby’s first stool and it does not normally pass stool until after the birth. The fetal heart rate in a distressed baby during labour and delivery could either be significantly above or below the normal range of 100–180 beats per minute.

SAQ 3.7 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.1, 3.2 and 3.6)

Which of the following statements is false? In each case explain what is incorrect.

A Maternal preference means respecting how the mother wants to give birth.

B In the first stage of labour the mother should not drink anything in case she vomits.

C The frequency of contractions refers to how painful the contractions become.

D Meconium discharging from the vagina is a sign of fetal distress.

E The ‘three cleans’ are clean hands, clean surface for the delivery and clean equipment.

Answer

A is true. Respecting maternal preferences includes how she wants to give birth.

B is false. During the first stage of labour the mother should drink at least one cup of fluid every hour to prevent dehydration.

C is false. The frequency of contractions refers to how often they come in every 10 minute period during the labour; it does not refer to how painful they become, which is the strength of contractions.

D is true. Meconium discharged from the vagina is a sign of fetal distress.

E is true. The ‘three cleans’ are clean hands, clean surface for delivery and clean equipment.