Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 8 March 2026, 5:11 AM

Labour and Delivery Care Module: 7. Neonatal Resuscitation

Study Session 7 Neonatal Resuscitation

Introduction

The moment when a baby is born is also the time when the birth attendant has to make a very rapid assessment of the condition of the newborn to decide whether it needs helping to breathe. Within a few seconds you have to be able to identify the general danger signs in a newborn that tell you to intervene quickly to protect it from developing serious complications, or even dying, because it is not able to get enough oxygen into its body. Of course, most babies breathe spontaneously as soon as they are born and all you need to do is follow the steps of basic newborn care, which were briefly outlined in Study Session 5 of this Module. You will learn them in much greater detail in the Module on Postnatal Care and the steps will be covered again in the Module on Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness.

However, in this study session our focus is on newborns who are not breathing well, and what you need to do in order to resuscitate them and get them breathing normally. You will learn how to distinguish between a healthy baby and one that is moderately or severely asphyxiated (i.e. short of oxygen due to breathing problems), and the correct action that you should take. This study session is unusual in that much of it is taught through diagrams.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 7

When you have studied this session you should be able to:

7.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 7.2)

7.2 Summarise the most important signs of neonatal asphyxia that mean you should begin neonatal resuscitation. (SAQ 7.1)

7.3 Explain how newborns can be helped to breathe by applying standard resuscitation techniques. (SAQs 7.1 and 7.2)

7.4 Identify the equipment you will need to give newborn resuscitation and how it should be used correctly. (SAQ 7.3)

7.5 Describe the things you should not do when assessing a newborn for possible breathing difficulties. (SAQ 7.4)

7.6 Summarise the main health risks to newborns and the activities that form the basis of essential newborn care. (SAQ 7.5)

7.1 Newborn respiration and resuscitation

We begin by briefly summarizing what usually happens when a newborn makes the transition from life in its mother’s uterus, to life in the outside world, where it must breathe for itself.

7.1.1 Breathing in a healthy newborn

Normally, a healthy baby starts to breath spontaneously immediately after delivery (Figure 7.1). If the breathing started spontaneously and is sustained by the baby without assistance, it indicates that:

- The fetus was not asphyxiated while in the uterus

- The respiratory system is functioning well

- The cardiovascular system (heart and blood vessels) is functioning well

- There is coordination by the brain of the movements required for sustained rhythmical breathing (brain is functioning well).

How do you check fetal wellbeing during labour and delivery?

A healthy fetus has a heart rate between 120–160 beats/minute. When the fetal membranes rupture, the amniotic fluid that leaks from the mother’s vagina is clear, not heavily blood-stained or coloured greenish-black by meconium — the baby’s first stool.

If you checked the fetal heart rate at regular intervals all through the mother’s labour, and recorded the result on the partograph (as you learned in Study Session 4), you should have referred any mother whose unborn baby showed signs of fetal distress. Therefore, it should be relatively uncommon for you to deliver an asphyxiated baby. However, complications in childbirth can develop unpredictably, or you may be called to a woman who is already far advanced in the second stage of labour when you reach her. Therefore, you need to know how to provide neonatal resuscitation in case you deliver an asphyxiated baby.

7.1.2 Newborn asphyxia

As you learned in Study Session 4 of this Module, asphyxia (shortage of oxygen) in the uterus is due to an inadequate supply of oxygen from the mother’s blood or a problem in the placenta. This may result in:

- Asphyxia at birth (mild, moderate or severe)

- Learning difficulties or cognitive impairment, which become apparent during childhood development; they are due to brain cells being destroyed by lack of oxygen during labour and delivery.

- Death of the newborn.

Gas exchange is when oxygen from the inhaled air is absorbed into the blood as it passes through the lungs, and waste carbon dioxide is released from the blood into the air that is breathed out

However, neonatal asphyxia is mainly due to failure of the newborn to breathe after birth, or its heart fails to pump enough blood to the lungs for gas exchange, or it has low haemoglobin levels (anaemia) so it cannot deliver enough oxygen around the body. The baby who cannot breathe cannot establish independent life outside the mother. Therefore, the purpose of neonatal resuscitation is to help the newborn to establish spontaneous breathing and facilitate oxygen delivery to its organs and tissues – particularly the brain, which is very quickly damaged by oxygen shortage. You may also need to resuscitate any baby that is severely anaemic due to blood loss during labour and delivery, or that continues to be cyanotic despite established breathing. Cyanosis is a bluish discolouration of the lips and skin, which occurs when there is insufficient oxygen in the blood (Figure 7.2).

To avoid the immediate and long-term complications of asphyxia, in addition to the labour and delivery care that you provide to the mother, and the routine newborn care of the baby (e.g. cutting the cord, keeping the baby warm), you also have to provide life-saving interventions for any newborn who cannot breathe properly.

7.2 Types of neonatal resuscitation

There are three techniques that you will learn about in this study session and in your practical skills training. They are:

- Ventilation: using a hand-operated pump called an ambu-bag (Figure 7.3), which pumps air into the baby’s lungs through a mask fitted over its nose and mouth. (You may hear health professionals referring to ventilation as ‘ambu-bagging’.)

Figure 7.3 Resuscitation technique practiced with a ventilator (ambu-bag) on a training doll. (Photo: Dr Yifrew Berhan)

Figure 7.3 Resuscitation technique practiced with a ventilator (ambu-bag) on a training doll. (Photo: Dr Yifrew Berhan) - Suctioning: using a device called a bulb syringe to extract mucus and fluid from the baby’s nose and mouth.

- Heart massage: pressing on the baby’s chest in a rhythmic way to stimulate the heartbeat (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4 Cardiac massage technique practiced on a training doll. You can see a ventilator at the top right of the picture. (Photo: Dr Yifrew Berhan)

Figure 7.4 Cardiac massage technique practiced on a training doll. You can see a ventilator at the top right of the picture. (Photo: Dr Yifrew Berhan)

7.2.1 Basic equipment needed for newborn resuscitation

- Two clean linen/cotton cloths: one to dry the newborn and one to wrap him or her afterwards

- Plastic bulb syringe to remove secretions from the mouth and nose, especially when meconium is present

- Ambu-bag and mask to give oxygen directly into the baby’s lungs

- A person trained in neonatal resuscitation (like you)

- Heat source (lamp) to provide warmth, if possible.

7.2.2 Before you start resuscitation

Before you apply any form of resuscitation, make sure that:

- The baby is alive: If the newborn doesn’t appear to be alive, FIRST listen to its chest with a stethoscope. If there is no heartbeat, the baby is already dead (see Table 7.1 below).

- You graded the extent of asphyxia: If you can hear a heartbeat, but you estimate it to be less than 60 beats/minute, apply heart massage first, then ventilate alternately on and off, till the heartbeat is above 60 beats/minute (see Table 7.1 below).

- The baby is not deeply meconium stained: If the baby’s skin is stained with meconium, or the oral and nasal cavities are filled with meconium-stained fluid (Figure 7.5), you should not resuscitate before suctioning the oral, nasal and pharyngeal areas. Ventilation will aggravate the baby’s breathing problem because it will force the meconium-stained fluid deep into the baby’s lungs, where it will block the gas exchange.

7.3 Assessing the degree of asphyxia

Moderate to severely asphyxiated babies usually require intensive resuscitation, so the next thing you have to learn is how to grade asphyxia in a newborn. Within no more than 5 seconds after the birth, you should make a very rapid assessment to find out whether the baby is alive or dead, and (if it is alive) to assess whether it has any degree of asphyxia. A severely asphyxiated baby may not breathe at all, there may be no movement of its limbs (arms and legs), and the skin colour may be deeply blue or deeply white. A baby who is not breathing at all after birth, or who is only gasping for breath, or who is breathing less than 30 breaths per minute needs help immediately. If a baby does not breathe soon after birth, it may get brain damage or die. Most babies who are not breathing can be saved if resuscitated correctly and quickly.

From Table 7.1, you can learn how to assess a newborn’s degree of asphyxia. Also look again at the three photos of newborns with different level of asphyxia (Figures 7.1, 7.2 and 7.5).

Gasping is when the newborn can take only a few breaths with difficulty and with wide gaps in between; it is usually a sign that the baby is close to death.

| Signs | No asphyxia | Mild asphyxia | Moderate asphyxia | Severe asphyxia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate | Above 100 beats/minute | Above 100 beats/minute | Above 60 beats/minute | Below 60 beats/minute |

| Skin colour | Pink | Mild blue | Moderately blue | Deeply blue |

| Breathing pattern | Crying | Crying | Breathing but not strong | Not breathing, or gasping type |

| Limb movement | Moving well | Weakly moving | Floppy | Floppy |

| Meconium-stained | No | No | Maybe | Usually |

| Resuscitation | No need | Fast response | Good response | Takes a long time to respond |

![]() Assessment of the degree of asphyxia should not take you more than 5 seconds. Do it fast but don’t panic.

Assessment of the degree of asphyxia should not take you more than 5 seconds. Do it fast but don’t panic.

Since neonatal resuscitation is an action that you need to perform rapidly (within one minute after delivery), it is better to estimate than to count the heart rate, and to observe the pattern of breathing rather than to count the respiratory rate. Table 7.2 gives you a simplified description of the signs that indicate what is normal and abnormal immediately after birth.

| Signs | Normal findings | Abnormal findings |

|---|---|---|

| Colour | Should be pink | Blue or cyanosed (shortage of oxygen) White, pallor (anaemia) Yellowish (jaundice) |

| Breathing | 40–60 breaths/minute | No breathing Breathing rate less than 30/minute Gasping (very few breaths with difficulty breathing) |

| Heart rate | 120–160 beats/minute | No heartbeat at all Heartbeat less than 100/minute |

| Muscle tone | Full term newborn has semi-flexed arms and legs (Figure 7.1) | Poor flexion of the limbs; arms and legs floppy (Figure 7.2), indicates moderate to severe asphyxia affecting the brain |

| Reflexes | Baby responds to a finger put into the roof of its mouth | No response to touching the roof of the baby’s mouth |

‘Less than’ can be replaced by the < symbol, as in <30/min. ‘More than’ can be replaced by the > symbol, as in >30/min.

7.4 Neonatal resuscitation procedures

Before you go to attend any delivery, you should make certain that you have prepared the equipment necessary to apply neonatal resuscitation and give immediate care to the newborn if required. In this section we move on to the actions that you should take once you have assessed the degree of asphyxia.

7.4.1 The first five seconds

Table 7.3 summarises what you should do in the first 5 seconds after the baby is born if the signs of asphyxia are present. After you have seen this overview, we will look at the specific actions in detail.

| What is the newborn doing? | Assessment | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Crying and moving limbs | Probably a healthy baby | Resuscitation not needed |

| Weak breathing, not moving limbs, moderate cyanosis | Probably moderately asphyxiated | Assist breathing by on and off ventilation (as described in Section 7.4.8) |

| Not crying, breathing or gasping; not moving limbs/floppy; may be cyanosed or meconium stained | Probably severely asphyxiated | Estimate heart rate Call an assistant (family member or other) Suction the oral, nasal and pharyngeal area in less than 5 seconds using a bulb syringe On and off ventilation |

| As above | Heart rate above 60 beats/minute | |

| As above | Heart rate below 60 beats/minute | As above, but with the addition of cardiac massage (see Figure 7.4) |

7.4.2 Checking the newborn’s heart rate

The apical heartbeat (or AHB) is just another name for the heartbeat heard through a stethoscope over the area of the heart on the left side of the chest, as shown in Figure 7.6. It is called ‘apical’ because the heartbeat is heard directly from the surface of the heart.

What is the name given to the number of heartbeats per minute measured away from the the heart?

It is called the pulse rate.

The newborn’s heartbeats can also be counted by feeling the pulse at the base of the umbilical cord, as shown in Figure 7.6.

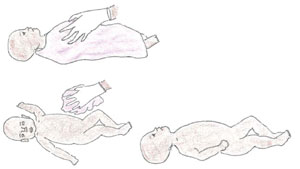

7.4.3 The initial actions

The list below sets out the actions you should take for all newborns in the sequence shown, irrespective of the degree of asphyxia:

- Fast drying as shown in Figure 7.8

- Keeping the baby warm.

- Clearing the mouth and nose as shown in Figure 7.9

- Apply gentle tactile stimulation to initiate or enhance breathing as shown in Figure 7.10

- Simultaneously assessing the degree of asphyxia as shown earlier in Tables 7.1 to 7.3

- Positioning the baby for resuscitation if there are signs of asphyxia, as shown in Figure 7.11

Now study each of these figures in turn. Look at them carefully and make sure that you read the captions and other notes associated with them.

7.4.4 Dry the baby quickly and keep it warm

Lay the baby on a warm surface away from drafts. Use a heat lamp or other overhead warmer, if available. Then dry the baby as shown in Figure 7.8.

Place the baby in skin-to-skin contact with the mother, covered by a warm blanket. Place a warm cap or shawl to cover the baby’s head.

7.4.5 Clearing the mouth and nose

If a bulb syringe is available:

![]() Suction the mouth first, then the baby’s nose (‘m’ before ‘n’) — see Figure 7.9.

Suction the mouth first, then the baby’s nose (‘m’ before ‘n’) — see Figure 7.9.

No deep suctioning with a bulb syringe! It can cause slowing of the heart rate (bradycardia).

If no bulb syringe:

Clear secretions from the mouth and nose with a clean, dry cloth.

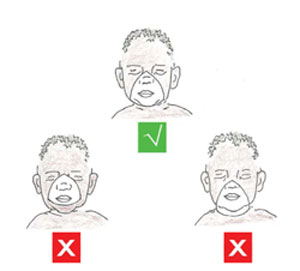

7.4.6 Apply gentle tactile stimulation to initiate or enhance breathing

![]() DO NOT stimulate by:

DO NOT stimulate by:

These types of stimulation are dangerous and can damage the newborn.

- Slapping the back

- Squeezing the rib cage

- Forcing the baby’s thighs into its abdomen

- Dilating the anal sphincter (the ring of muscle that closes the anus)

- Hot or cold compresses or baths

- Shaking the umbilical cord.

7.4.7 If you diagnose asphyxia, start resuscitation!

Position the newborn on his or her back with the neck slightly extended as shown in the top picture in Figure 7.11. Open the airway by clearing the mouth and nose with suction using the bulb syringe as you saw previously in Figure 7.9.

- Position yourself at the head of the baby (see Figure 7.12).

If the apical heartbeat is > (more than) 60 beats/minute:

- Ventilate with the appropriate size of mask and a self-inflating ambu-bag. The mask should be fitted as shown in Figure 7.13. Make a firm seal between the mask and the baby’s face, so air cannot escape from under the edges of the mask. But don’t force the mask down onto the baby’s face, because this could push its chin down towards its chest (bottom diagram in Figure 7.11) and compress its airway.

If the apical heart beat is < (less than) 60 beats/minute:

- Apply heart massage (look back at Figure 7.4) and ventilate alternately (on and off ventilation) with the ambu-bag.

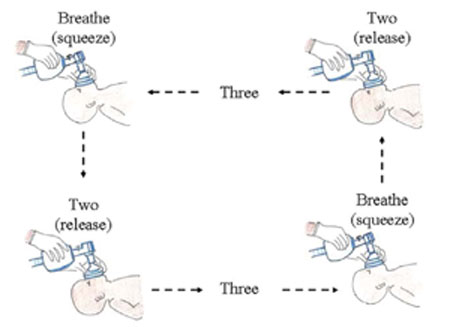

7.4.8 Ventilate at 40 breaths per minute

Count out loud: ‘Breathe — two — three’ as you ventilate the baby (see Figure 7.14). Squeeze the bag as you say ‘Breathe’ and release the pressure on the bag as you say ‘two — three’. This helps you to ventilate with an even rhythm, at a rate that the newborn’s lungs are naturally adapted to.

The amount of air you are moving into and out of the lungs is the equivalent of about 40 breaths per minute. Apply enough pressure to create a noticeable, gentle rise and fall in the baby’s chest. The first few breaths may require higher pressures, but if the baby appears to be taking a very deep breath, you are using too much pressure.

7.4.9 Evaluate the baby during ventilation

The best sign of good ventilation and improvement in the baby’s condition is an increase in heart rate to more than 100 beats/minute.

What other change would you expect to see in the baby while you are ventilating it, if the resuscitation is going well?

You would expect to see the baby’s skin colour change from bluish or very pale, to a healthier pinkish colour. You may also see the baby begin to move a little bit, beginning to flex its limbs and look less floppy.

When you stop ventilating for a moment, is the baby capable of spontaneous breathing or crying? These are good signs. Many babies recover very quickly after a short period of ventilation, but keep closely monitoring the baby until you are sure it is breathing well on its own.

If the baby remains weak or is having irregular breathing after 30 minutes of resuscitation, refer the mother and baby urgently to a health centre or hospital where they have facilities to help babies who are having difficulty breathing. Go with them and keep ventilating the baby all the way. Make sure it is kept warm at all times. Newborns easily lose heat and this could be fatal in a baby that can’t breathe adequately on its own.

Figure 7.15 summarises the steps in newborn resuscitation which you have learned in Section 7.4.

7.5 Immediate essential newborn care

We end this study session with a reminder about essential newborn care, which you should conduct with all babies, regardless of whether they have any signs of asphyxiation. When the baby’s umbilical cord is cut, there are many physiological changes inside the baby’s body to allow it to make the necessary adaptation to life outside its mother. It is generally tougher to survive in the outside world than in the relative safety of the uterus, so we need to provide basic care to the newborn to help it resist some potential health risks listed in Box 7.1.

Box 7.1 Health risks to newborns

Newborns need additional care to prevent:

- Spontaneous bleeding, usually from the gastrointestinal tract, due to Vitamin K deficiency

- Bleeding due to birth trauma (usually manifested late after delivery with swelling over scalp that requires immediate referral)

- Eye infections due to Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea (bacteria which are common causes of sexually transmitted infections; the baby can acquire these infections as it passes through the birth canal)

- Some vaccine preventable diseases such as poliomyelitis and tuberculosis

- Hypothermia (becoming too cold)

- Hypoglycaemia (low blood glucose level)

- Mother-to-child transmission of HIV, if the mother is HIV-positive.

Vaccine preventable diseases are discussed in detail in the Communicable Diseases Module, Study Sessions 3 and 4.

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV is covered in the Antenatal Care Module, Study Session 17; the drugs and procedures for PMTCT are given in the Communicable Diseases Module, Study Session 27.

With the health risks in Box 7.1 in mind, make sure that you give all newborn babies the following essential care:

- Tie the umbilical cord two finger-widths from the baby’s abdomen and place a second tie two finger-widths away from the first one. Cut the cord between the first and second ties. Check that the umbilical cord stump is not bleeding and is not cut too short

- Apply tetracycline eye ointment once only, to prevent eye infections.

- Inject vitamin K (1 mg, intramuscularly) into the front of the baby’s mid-thigh to prevent spontaneous bleeding.

- Give the first dose of oral polio vaccine and BCG vaccine (against tuberculosis) according to the guidelines in the Ethiopian Expanded Programme of Immunization (EPI).

- The body temperature of the newborn must remain above 36oC. Place the baby on the mother’s abdomen in skin-to-skin contact with her, where it can breastfeed. Cover them both with a blanket and put a warm hat or shawl over the baby’s head.

- Ensure that the baby is suckling well and the mother’s breast is producing adequate milk. If breastmilk is not preferred, make sure that adequate replacement feeding is ready. Initiate early and exclusive breastfeeding unless there are good reasons to avoid it, e.g. in an HIV-positive mother.

- The baby should get preventive treatment to protect it from HIV if its mother is HIV-positive.

The vaccination schedule for all the vaccines in the EPI are described in full in the Immunization Module.

You will learn all about breastfeeding in the Postnatal Care Module. Breastfeeding and HIV are covered in the Communicable Diseases Module, Study Session 27.

Summary of Study Session 7

In Study Session 7, you have learned that:

- The most important signs of asphyxiation in newborns at delivery are: difficulty breathing, gasping or no breathing; abnormal heart beat; poor muscle tone (floppy limbs); lack of movement; bluish skin colour (cyanosis), and being stained with meconium.

- Assessment of the degree of asphyxia should be done in the first 5 seconds after the birth, at the same time as commencing basic newborn care (e.g. drying the baby, keeping it warm, tying and cutting the cord, etc).

- Swift action is necessary to begin resuscitating a baby who is not breathing well, after you have suctioned its mouth and then its nose.

- Check that the baby is alive (listen for an apical heartbeat); that the heart rate is above 60 beats/minute (begin heart massage before resuscitation if the heart rate is less than 60 beats/minute); and that the baby is not stained with meconium, which must be suctioned out before resuscitation can begin.

- Position the baby with its neck extended to open the airways; place a correctly fitting ventilation mask over the baby’s mouth and nose, and begin ventilating at a rate of about 40 breaths per minute.

- Watch for signs of improvement: e.g. pinkish colour, movement, ability to breathe unaided, etc. Refer urgently if this has not been achieved after 30 minutes of ventilation.

- Remember to conduct all the activities of essential newborn care, including cord care, giving a vitamin K injection and tetracycline eye ointment, establishing early and exclusive breastfeeding, and ensuring that anti-HIV medication is given to prevent mother-to-child-transmission.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 7

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

First read Case Study 7.1 and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 7.1 Atsede’s baby can’t breathe

A 25 year-old woman called Atsede was brought to your Health Post after being in labour for 38 hours at home. Soon after she reached you, she gave birth to a full term baby boy. You assessed the baby and found he was not making any breathing effort, he had no movement of his limbs and his whole body was covered with meconium-stained amniotic fluid. When you dried him and applied tactile stimulation, the baby still didn’t show any effort to breathe.

SAQ 7.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 7.2 and 7.3)

- a.Is this baby asphyxiated? If yes, what is the degree of asphyxia?

- b.What are your immediate next steps? Then what do you do?

- c.Could the birth complication in this newborn have been prevented, and if so, how?

Answer

- a.Atsede’s baby is severely asphyxiated. The danger signs are that he was not making any breathing effort, or moving his limbs, he was covered with meconium and tactile stimulation had no effect.

- b.Your next step is to dry him quickly, wrap him warmly, and remove meconium from his mouth and nose with the bulb syringe and a clean cloth. Listen for an apical heartbeat and if it is below 60 beats/minute, begin heart massage, alternating with ventilating the baby at about 40 breaths per minute.

- c.The birth complication in this newborn could have been prevented by Atsede receiving skilled birth attendance much earlier in her labour from someone who could monitor the signs of fetal distress and refer her for emergency care; 38 hours is too long to wait.

SAQ 7.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 7.4

List the basic equipment you will need in order to resuscitate a newborn with breathing difficulties.

Answer

The basic equipment you will need in order to resuscitate a newborn with breathing difficulties are:

- Two clean linen/cotton cloths: one to dry the newborn and one to wrap him or her afterwards

- Plastic bulb syringe to remove secretions from the mouth and nose, especially when meconium is present

- Ambu-bag and mask to give oxygen directly into the baby’s lungs

- A person trained in neonatal resuscitation (like you)

- Heat source (lamp) to provide warmth, if possible.

SAQ 7.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 7.1, 7.2, 7.4, 7.5 and 7.6)

Which of the following statements is false? In each case say what is incorrect.

A If a newborn cries soon after birth, it is a sign of asphyxia occurring before delivery.

B Cyanosis means being covered with meconium all over the body.

C The apical heartbeat can be detected by listening to the baby’s chest with a stethoscope.

D Gas exchange in the lungs happens when carbon dioxide is breathed in and oxygen is breathed out.

E Giving the newborn a Vitamin K injection is to prevent eye infections.

F The recommended ventilation rate for newborns is 40 breaths/minute.

Answer

A is false. If a newborn cries soon after birth, it is a sign of asphyxia occurring before delivery.

B is false. Cyanosis means having a bluish colour to the skin because of oxygen shortage (asphyxia).

C is true. The apical heartbeat can be detected by listening to the baby’s chest with a stethoscope.

D is false. Gas exchange in the lungs happens when carbon dioxide is breathed out and oxygen is breathed in.

E is false. Giving the newborn a vitamin K injection is to prevent spontaneous bleeding; tetracycline ointment is given to prevent eye infections.

F is true. The recommended ventilation rate for newborns is 40 breaths/minute.

SAQ 7.4 (tests Learning Outcome 7.4)

Which of the following ways of stimulating the newborn are recommended, and which are dangerous and not allowed?

- Slapping the back

- Rubbing the abdomen gently up and down

- Squeezing the rib cage

- Forcing thighs into the abdomen

- Flicking the underside of the baby’s foot with your fingers

- Dilating the anal sphincter

- Hot or cold compresses or baths

- Shaking the umbilical cord.

Answer

Only two of the ways in the list are recommended for gentle tactile stimulation of the baby:

- Rubbing the abdomen gently up and down

- Flicking the underside of the baby’s foot with your fingers.

All the other ways listed are dangerous and should not happen.

SAQ 7.5

Table 7.1 summarises some common health risks to newborns and the immediate essential care to prevent those complications. Some of the boxes have been left blank for you to complete.

| Newborn health risk | Essential newborn care |

|---|---|

| Eye infection |

|

| Spontaneous bleeding |

|

| Hypothermia |

| Hypoglycaemia |

Answer

The completed Table 7.1 is below.

| Newborn health risk | Essential newborn care |

|---|---|

| Eye infection | Apply tetracycline eye ointment |

| Spontaneous bleeding | Inject 1 mg vitamin K intramuscularly |

| Skin-to-skin contact with mother, blankets and cap | Hypothermia |

| Early breastfeeding or adequate replacement feeding | Hypoglycaemia |