Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 8 March 2026, 5:11 AM

Labour and Delivery Care Module: 10. Ruptured Uterus

Study Session 10 Ruptured Uterus

Introduction

Ruptured uterus is a tearing or bursting of the uterus due to the pressure exerted by an obstructed labour. Uterine rupture is very prevalent in developing countries like Ethiopia, where around 94% of deliveries occur at home with no skilled health professional attending the labour. When labour ends with a ruptured uterus, the usual consequences for the woman (if she survives), are losing her baby and losing her uterus.

Almost all cases of uterine rupture occur among multiparous women, who have previously given birth at least once after their baby reached 28 weeks of gestation. You will find out why this is so later in this study session. Uterine rupture can also occur among women with a scarred uterus, if the scar tissue tears open. However, in Ethiopia and other developing countries, almost all cases of uterine rupture occur in women with an unscarred uterus whose labour became obstructed when noone was present to intervene. In this study session you will learn about the risk factors and clinical features of ruptured uterus, its consequences for the mother and the baby, and how to institute life-saving interventions.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 10

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

10.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 10.1 and 10.2)

10.2 Describe the predisposing factors for uterine rupture and explain why multiparous women are at greater risk than first-time mothers. (SAQ 10.2)

10.3 Describe the warning signs and clinical features of uterine rupture and the common complications that result from it. (SAQs 10.3 and 10.4)

10.4 Explain how you would perform life-saving interventions for women with a ruptured uterus, and what actions you would take to reduce the risk of uterine rupture during labour. (SAQ 10.4)

10.1 Predisposing factors for a ruptured uterus

The uterus of a woman in labour may rupture if the delivery is obstructed (for any reason) while the uterus continues contracting until it tears or bursts. You already know a lot about the complications of labour and delivery from Study Sessions 8 and 9, so you should be well prepared to answer the following question.

What factors can you suggest that would increase the risk of a ruptured uterus occurring?

Uterine rupture may occur if the labour is obstructed due to:

- Cephalopelvic disproportion (the fetal head is too large or the mother’s pelvis is too small to allow the baby to descend down the birth canal).

- Persistent malpresentation or malposition of the fetus (e.g. breech, face, brow or shoulder presentation, or the baby is head down (vertex presentation) but in the occipito-posterior position (with the back of its skull towards the mother’s back).

- Multiple pregnancy (twins or more babies, especially if they are ‘locked’ at the neck or conjoined/fused together).

- Physical obstruction preventing the baby from descending (e.g. a tumour in the abdomen or uterus).

- Scarring of the uterus (which we referred to in the introduction to this study session).

The first four causes have already been covered in detail in earlier study sessions, but there is more to be said about uterine scarring and some other reasons why uterine rupture may occur.

10.1.1 Uterine scarring

A woman who has had previous surgery on her uterus – for example, to deliver a baby by caesarean section, or to remove a uterine tumour – will be left with scar tissue where the severed uterine wall has healed. Scar tissue is less flexible than the intact wall of the uterus and it cannot stretch evenly during labour contractions. If the labour is obstructed for a long time, the powerful contractions of the muscle layer in the uterine wall may cause the scar tissue to tear open. Another reason for scarring of the uterus is if it was perforated during an abortion for a previous pregnancy.

10.1.2 Scarred cervix

The cervix may also have been damaged during a previous delivery, for example by forceps used to help deliver a baby that was failing to make progress after the head had crowned. Or cervical damage may have resulted if surgical instruments were inserted into the uterus via the vagina, for example to control postpartum haemorrhage, or to treat a problem in the uterus such as inflammation of the uterine lining. In any of these cases the injured cervix will develop scar tissue after healing that may burst open during an obstructed labour.

Do you recall from the Antenatal Care Module, what names are given to the muscle layer in the uterus and the inner lining of the uterus (where the placenta forms)?

The muscle layer is called the myometrium, and the inner lining is the endometrium.

10.1.3 Previously repaired fistula

You learned about fistula in Study Session 9. It is one of the most serious complications of obstructed labour and is highly prevalent in the rural areas of Ethiopia. If a woman developed a fistula during a previous labour, which was then surgically repaired, the scarring that developed as the fistula healed may have been so extensive that it obstructs the delivery of the next baby.

Which part of the birth canal will be scarred by a repaired fistula?

The vagina: a fistula is a torn opening between the vagina and either the urinary bladder, the rectum, the urethra or the ureter.

![]() Women who are known to have a scarred uterus, cervix or vagina should be strongly advised to deliver their next baby in a health facility with a blood transfusion service and the surgical equipment and expertise to perform a caesarean delivery if the need arises.

Women who are known to have a scarred uterus, cervix or vagina should be strongly advised to deliver their next baby in a health facility with a blood transfusion service and the surgical equipment and expertise to perform a caesarean delivery if the need arises.

10.2 Why are multiparous women more at risk of uterine rupture?

A multiparous woman is one who has previously given birth to at least one baby after 28 weeks of gestation. The gestational age is significant, because by 28 weeks the fetus will have reached a substantial size and weight, so the multiparous woman’s uterus will already have been stretched. One result of this stretching is that the delivery is expected to be easier in subsequent pregnancies – which is, indeed, usually the case. Despite this fact, multiparous women are more likely than primiparous (first-time) mothers to experience uterine rupture if their labour is obstructed.

Can you suggest a reason for this unexpected finding?

One reason is that first-time mothers do not have a previous history of complicated delivery, whereas a woman who has given birth before may have already had complications which caused scarring of the uterus or other parts of the birth canal. Such scarring is a risk factor for a ruptured uterus.

10.2.1 Uterine inertia

Another reason why multiparous women with prolonged or obstructed labours are more at risk of uterine rupture relates to the fact that they continue experiencing powerful labour contractions for much longer than first-time mothers.

In primiparous women, the uterine contractions remain relatively strong only for about the first 24 hours of labour, after which the contractions become weaker in intensity and shorter in duration. After about 36 hours, in the majority of primiparous women, the uterus is exhausted and they develop uterine inertia, which is when the contractions become very weak in intensity, with a short duration and long intervals between them. For such first-time mothers, because uterine contractions have almost ceased, uterine rupture is a rare phenomenon. By contrast, the risk to multiparous women whose labour is obstructed is that the uterine contractions remain forceful and frequent for very much longer, and as a result the uterus is more likely to rupture.

Primiparous women do face other serious problems, however, because uterine inertia means that the fetal head will stay in the maternal pelvis for a long time. This increases the risk of fetal hypoxia (oxygen shortage), and fistula formation, retention of urine and infection in the obstructed bladder of the mother.

10.2.2 Traditional abdominal massage

In some parts of Ethiopia, abdominal massage during labour is a common cultural practice, particularly when labour is prolonged. Traditional birth attendants or village women use butter and other lubricants to rub the abdomen and apply pressure on the fundus (rounded top) of the uterus to try to push the baby downwards. This is an extremely harmful traditional practice since it can lead to a ruptured uterus, especially in multiparous women (for the reasons given above).

10.2.3 Inappropriate use of uterotonic agents

Whenever you use a uterotonic drug (drugs that cause uterine contraction, e.g. misoprostol, oxytocin or ergometrine) for active management of the third stage of labour (recall Study Session 6), you must first check that there is no other fetus in the uterus. This is because if you mistakenly administer a uterotonic agent when there is still a fetus in the uterus, it will contract so powerfully that it can easily rupture, especially in the case of multiparous women. Also it is likely to asphyxiate the baby.

Why are multiparous mothers at greater risk of a ruptured uterus than primiparous women?

Scarring of the uterus is a major risk factor in uterine rupture, because scar tissue is less flexible and may tear open during contractions. A multiparous woman may have scars from a caesarean, or from a complicated earlier delivery which damaged the birth canal. Also, her uterus will go on contracting for a long time without developing uterine inertia, even if the labour is obstructed.

10.3 Clinical features and consequences of ruptured uterus

Uterine rupture is totally preventable if all cases of prolonged labour are managed effectively and appropriate action is taken before the uterus spontaneously ruptures.

10.3.1 Warning signs of imminent uterine rupture

Box 10.1 shows the common warning signs of imminent uterine rupture. These are the best indicators that the labour is obstructed and that, unless the baby is quickly delivered by surgical operation, the uterus is very likely to rupture soon.

Box 10.1 Warning signs of uterine rupture

- Frequent, strong uterine contractions, occurring more than 5 times in every 10 minutes, and/or each contraction lasting 60–90 seconds or longer.

- Fetal heart rate above 160 beats/minute, or below 120 beats/minute, persisting for more than 10 minutes – this is often the earliest sign of obstruction affecting the fetus.

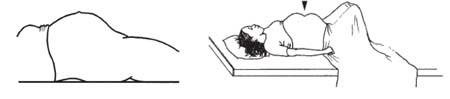

- Bandl’s ring formation (see Study Session 9 and Figure 10.1).

- Tenderness in the lower segment of the uterus.

- Possibly also vaginal bleeding.

How can the partograph aid you in spotting the potential imminence of uterine rupture?

Since you use it to chart the frequency and duration of contractions, as well as changes to the fetal heartrate, you will quickly see if either of these is in the warning zone indicated in Box 10.1 above.

10.3.2 Signs that the uterus has ruptured

The first sign that the uterus has ruptured is that the contractions stop completely. Other signs rapidly follow.

Tender swollen abdomen

Tenderness is pain elicited when you touch the abdomen. The abdomen is tender because of the rupture in the uterus and irritation caused by blood accumulating in the abdominal cavity. The abdomen appears distended (swollen) because the uterus is initially totally wrapped around the fetus and blood is escaping into the abdominal cavity. Bowel movement will be reduced or absent (paralytic ileus) so you will not be able to hear bowel sounds with your stethoscope. The bladder may also be obstructed, which contributes to the swelling and tenderness. As time passes, infection may develop in the abdomen, which will cause additional swelling.

Easily palpable fetal parts, absent movement and fetal heart sounds

The fetus cannot survive long in a ruptured uterus. After the initial wrapping of the uterus tightly around its body, parts of the fetus may emerge through the rupture, or the entire fetus may escape from the uterus into the abdominal cavity. When this happens, if you palpate the abdomen, only the abdominal wall will be between your hand and the fetus, so you will be able to feel the fetal parts easily. If the baby has died, the mother will not feel it moving, and you will not be able to hear a fetal heartbeat.

10.3.3 Consequences for the mother

The consequences of the rupture for the mother depend on the extent of the blood loss, how much time has passed since the rupture occurred, and whether her abdominal cavity and blood system are infected.

Extent of blood loss

Uterine rupture by its nature is a trauma to the uterine tissue where there will be tearing of uterine muscles and blood vessels. If the rupture involves major blood vessels, particularly uterine arteries, the blood loss will be massive. Unless rapid emergency intervention occurs, the blood loss will almost certainly cause the death of the fetus, and the mother will be in severe haemorrhagic shock (described below), which will be followed by her death. If the rupture occurs in an area of the uterus where major blood vessels aren’t involved, the woman has a greater chance of survival.

The duration of the rupture

It often happens that rural women, who are not haemorrhaging excessively and whose condition does not appear to them or their families to be immediately life-threatening, will remain at home for hours, even days, after the uterus has ruptured. However, the longer the woman remains untreated with a ruptured uterus, the higher the chance of greater blood loss, acute kidney failure and infection which has disseminated (spread) throughout her body.

Presence of established infection

A ruptured uterus means there is direct communication between the birth canal and the abdominal cavity. Other internal organs, including parts of the intestines, rectum and bladder may also have been damaged and be leaking their contents into the abdomen. As a result, microorganisms can easily spread around the whole of the abdominal cavity, and enter the blood circulation through the ruptured blood vessels. The development of infection in the abdominal cavity is called peritonitis; infection disseminated around the body in the blood circulation is called septicaemia. If the woman survives the initial rupture but remains untreated for more than about 6 hours, the risk of one or both of these conditions occurring is very high indeed. Therefore, early recognition that a rupture has occurred and early referral are of paramount significance in saving the life of the mother.

Depending on the extent of blood loss, duration of time since the rupture and status of any infection, the woman with a ruptured uterus may develop some or all of the complications described below.

Haemorrhagic shock

The signs of this rapidly fatal condition are that the mother has or feels:

- Faint, dizzy, weak or confused

- Pale skin and cold sweats

- Fast pulse (above 100 beats/minute) or too fast to be recordable

- Rapidly dropping or unrecordable blood pressure

- Fast breathing (above 30 breaths/minute)

- Sometimes loss of consciousness

- Significantly reduced or absent urine output.

Septic shock

This occurs if the rupture and haemorrhage have resulted in septicaemia. The signs are the same as for haemorrhagic shock, but with the addition of high grade fever (above 38oC).

Other complications

- Peritonitis: infection in the abdominal cavity.

- Acute kidney failure due to low blood volume.

- Almost all cases coming to hospitals will be managed by removing the uterus (a hysterectomy), so the woman will be unable to have more children.

What happens to the fetus at the stage of an imminent ruptured uterus and immediately afterwards?

Before the rupture its heart rate is persistently above 160 beats/minute, or below 120 beats/minute. After the rupture the uterus wraps itself around the fetus, and with blood draining into the abdominal cavity, it quickly dies unless there is immediate surgery to remove it.

10.4 Interventions in ruptured uterus

The following guidelines will help you to prevent or reduce the risk of ruptured uterus occurring in labouring women in your community:

- Use the partograph to follow the progress of a woman in labour, to ensure you get early warning if the labour is not progressing normally (you learned how to use the partograph in Study Session 4 of this Module).

- Refer women quickly if you suspect the labour is prolonged or obstructed (see referral criteria below).

- Advise all multiparous women with a potentially scarred uterus (because of complications with an earlier birth) to deliver in a health facility with the capacity for blood transfusion and caesarean delivery. Give the same advice to any woman who has had a uterine tumour removed.

- Explain to community members why it is important not to massage the uterus during labour, or apply pressure on the uterus to try to hasten delivery; ask them not to do this even though it is a traditional practice.

- Use uterotonic drugs to help deliver the placenta, but only after checking that the last fetus has been delivered.

10.4.1 Referral criteria for prolonged labour

Do not allow a woman to remain for a long time in the first or second stages of labour without making an efficient referral.

When should you refer a multiparous or primiparous woman whose labour is prolonged? (Think back to Study Session 9.)

Referral for prolonged labour should happen for all women if:

- The latent first stage of labour lasts more than 8 hours before entering into the active first stage

- The active first stage lasts more than 12 hours before entering into the second stage

- The second stage of labour lasts more than one hour in a multiparous woman, or more than two hours in a primiparous woman, unless the birth of the baby seems to be imminent.

Your major role is primary prevention – in this case, making sure that if there is obstructed labour, you can get the woman to a health facility for emergency care in time to prevent uterine rupture. However, there are many reasons why you may have to give emergency care yourself to a woman with a ruptured uterus, where your role will be secondary prevention of the complications associated with uterine rupture.

10.4.2 Primary prevention: getting to a health facility for emergency care before uterine rupture

Think back to what you learned in the Antenatal Care Module (Study Session 13) and the discussion there about making a referral. What must you remember to do?

You should:

- Write a referral note with as much detail as possible.

- Mobilise the community’s emergency transport plan for the mother. Go with her if you can.

- If possible, warn the health facility to expect her. If there is a choice of health facility at roughly equal distance, check which one has facilities for emergency surgery and blood transfusion and send her there.

10.4.3 Secondary prevention: emergency care for a woman in shock

![]() A woman in shock needs help fast. You must treat her quickly to save her life.

A woman in shock needs help fast. You must treat her quickly to save her life.

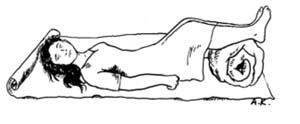

Shock is an inevitable consequence of a ruptured uterus. So you refer her quickly to the nearest health facility with the necessary emergency care services. On the way, have the woman lie with her feet higher than her head, and her head turned to one side (Figure 10.2). Keep her warm and calm.

If you have been trained to do so, begin to give her intravenous fluids. You learned how to do this in the Antenatal Care Module, Study Session 22, and in your practical skills training. If she is conscious, she can drink water or rehydration fluids (oral rehydration salts, ORS). If she is not conscious, do not give her anything by mouth - no medicines, drink or food.

Other important preparations that you should already have put in place are to:

- Ensure that your antenatal advice explained clearly to the woman the importance of having skilled help when she goes into labour

- Persuade the woman’s family and her community to make a plan in advance for possible emergencies, including transport and financial support

- Make sure that you are well versed and skilled in making an early diagnosis and conducting pre-referral emergency procedures

- Make sure the woman goes to the health facility accompanied by at least two fit adult persons who can be potential blood donors, and go with her if you can.

Finally, try to reduce the possibility of any delay, which can mean the difference between life and death. The reasons why so many Ethiopian women die of a ruptured uterus are reluctance to seek skilled help at birth and then delay in seeking medical help following a rupture; further delay in getting treatment because of distance to a health facility; or lack of equipment and appropriately trained personnel when the woman arrives for emergency care.

If you remember all these points you will have the best possible chance of ensuring that the woman is quickly referred to the most appropriate facility for emergency intervention and care.

Summary of Study Session 10

In Study Session 10 you have learned that:

- In Ethiopia, uterine rupture most often occurs because of neglected obstructed labour. With early intervention and appropriate care, uterine rupture is almost entirely preventable.

- More cases of uterine rupture occur among multiparous women than among primiparous women. One reason is that in primiparous woman uterine intertia acts to prevent contractions remaining forceful and frequent for such a long time that uterine rupture occurs.

- Uterine inertia in primiparous women has other risks: because the fetal head stays in the pelvis for a long time there is increased risk of fetal hypoxia, fistula formation, retention of urine and infection of the bladder.

- The main predisposing factor for uterine rupture is an obstructed labour, which may be due to cephalopelvic disproportion, malpresentation/malposition of the fetus, multiple pregnancy, a uterine tumour, or scarring. Other factors increasing the risk of rupture include a previously repaired fistula, injudicious use of uterotonic drugs, and abdominal massage during labour by traditional healers.

- The clinical features of imminent uterine rupture are persistent uterine contractions of 60–90 seconds duration or longer, occurring more than 5 times in every 10 minutes, fetal heartbeat derangement (persistently above 160 beats/minute or below 120 beats/minute), Bandl’s ring formation, abdominal tenderness, and maybe vaginal bleeding.

- The key sign that a uterus has ruptured is that contractions stop completely.

- Other signs of a ruptured uterus may include abdominal tenderness, easily palpable fetal parts, abdominal distension, absence of fetal kick and absence of fetal heartbeat.

- The clinical condition of a woman with a ruptured uterus depends on the extent of blood loss, duration of rupture and presence of established infection.

- Common complications of uterine rupture are fetal death, maternal death, infection and haemorrhagic and/or septic shock, peritonitis, acute kidney failure, and surgical removal of the uterus

- Some reasons why so many Ethiopian women die of a ruptured uterus are: reluctance to seek skilled help at birth and then delay in seeking medical help following a rupture; further delay in getting treatment because of distance to a health facility; or lack of equipment and appropriately trained personnel when the woman arrives for emergency care.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 10

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 10.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1 and 10.2)

What are the main factors that may predispose a woman to develop a uterine rupture?

Answer

Factors predisposing a woman to develop a uterine rupture (key words in bold) are:

- Obstructed labour caused by: the fetal head being too large or the mother’s pelvis being too small for the baby to descend through the birth canal (cephalopelvic disproportion); malpresentation and malposition of the fetus; or multiple pregnancy (see Study Session 8 for details of all these).

- Other physical obstructions such as a tumour, or scarring from damage at a previous birth (e.g. a fistula, a torn opening between the vagina and bladder, rectum, urethra or ureter).

- Traditional practices, e.g. inappropriate abdominal massage or pushing down on the fundus during labour.

- Inappropriate use of a uterotonic drug (used to cause contractions).

SAQ 10.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1 and 10.2)

Why are multiparous women at greater risk of uterine rupture than primiparous women?

Answer

Primiparous women are giving birth for the first time. In a first birth there is the likelihood of a longer labour. However, in primiparous women, uterine inertia (contractions become weaker and shorter, with longer intervals) occurs after about 36 hours, greatly reducing the risk of uterine rupture.

In contrast, in multiparous women have had at least one baby after 28 weeks’ gestation, the uterus will go on contracting strongly for much longer than the primiparous uterus. If obstruction prevents delivery for a long time, particularly if there is scarring from a complicated earlier birth, the uterus is much more likely to rupture.

SAQ 10.3 (tests Learning Outcome 10.3)

Complete Table 10.1 below by adding details of the warning signs of a possible uterine rupture.

| Actions | Warning signs |

|---|---|

| Timing the stages of labour |

|

| Timing the uterine contractions |

|

| Checking the fetal heart rate |

|

| Checking the abdomen |

|

Answer

The completed version of Table 10.1 appears below.

| Actions | Warning signs |

|---|---|

| Timing the stages of labour | Labour is prolonged: latent first stage lasts more than 8 hours; active first stage lasts more than 12 hours; second stage lasts more than 1 hour in a multipara, or more than 2 hours in a primipara |

| Timing the uterine contractions | Persistent uterine contractions of 60-90 seconds duration or longer, occurring more than 5 times in every 10 minutes |

| Checking the fetal heart rate | Fetal heart rate persistently above 160 beats/minute or below 120 beats/minute |

| Checking the abdomen | Lower segment of the uterus is tender on palpation; Bandl’s ring is present |

| Checking the vagina | Vaginal bleeding may be present |

SAQ 10.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.3 and 10.4)

- a.What complications may follow uterine rupture?

- b.What actions should you take if uterine rupture occurs?

Answer

- a.Complications of uterine rupture include:

- Death of the fetus unless there is immediate surgery to remove it.

- Severe haemorrhage and haemorrhagic shock for the mother (identified by faintness, pale skin, fast pulse, dropping blood pressure, fast breathing, lapses into unconsciousness, reduced urine output) leading to death of the mother unless she gets immediate treatment.

- Infection: peritonitis (infection of the abdominal cavity) and/or septicaemia (bacterial infection of the blood), leading to potentially fatal septic shock.

- Acute kidney failure (because of loss of blood volume).

- Hysterectomy.

- b.The most important action is to get the woman to the nearest health facility capable of dealing with a ruptured uterus as quickly as possible; she needs to be kept warm and calm, lying down with feet higher than ‘her’ head and her head on one side. You should give her intravenous fluids. If she is unconscious do not give anything by mouth.