Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 12 February 2026, 5:07 PM

Non-Communicable Diseases, Emergency Care and Mental Health Module: 10. Assessing a Person with Mental Illness

Study Session 10 Assessing a Person with Mental Illness

Introduction

Mental disorders vary in degree or severity from a mild illness that causes limited suffering to severe conditions that cause marked distress to the person with the illness and their families. The more extreme and distressing disorders are simply termed severe mental illness (SMI). Individuals with SMI are those with an illness that severely restricts their day-to-day activities, such as working in the fields, attending expected community activities like funerals, and carrying out their family responsibilities.

Like many healthworkers, you have probably come across individuals with SMI (Figure 10.1) and may have felt you cannot properly assess or speak to them. This feeling may partly be because you think it is difficult to make sense of what a person with SMI says, or you may feel intimidated by thinking that their behaviour can be unpredictable. These feelings and thoughts are not unique to you. Many health professionals without experience in mental health feel this way. This study session will help you to see mental health problems – including SMIs – more realistically.

We begin with describing the most common mental illnesses in communities like yours, and give their classification in terms of severity. We will then describe how you can detect people with mental illness in your community. You will also learn about the common risks associated with mental disorders and how you can assess these risks, with the main focus on self-harm and suicide. Further details on general assessment of mental illness will be provided in Study Session 11.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 10

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

10.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 10.1 and 10.2)

10.2 List the common symptoms that people with one of the main categories of severe mental illness may have. (SAQ 10.1)

10.3 Describe the main ways in which the more serious mental illnesses are classified, including the priority mental health disorders. (SAQ 10.1)

10.4 Describe the main risks associated with mental disorders, particularly those relating to self-harm and suicide. (SAQ 10.2)

10.5 Describe how mental disorders and the risks associated with them can be assessed by careful questioning. (SAQ 10.2)

10.1 How common are mental health problems?

People often think that a person with mental illness is someone who speaks nonsense, is unpredictable and behaves in strange or bizarre ways. But people with mental illness are not different to other ‘ordinary’ people. They are ordinary people with a condition. Evidence also tells us that people with mental illness are no more violent or dangerous than people that have malaria or back pain (Figure 10.2).

Mental disorders are relatively common in every community. For every ten people that you see on your house-to-house visits, at least one will have some form of mental health problem. For every 50 adults that you see in your house-to-house visits, one will have an SMI. You will also come across individuals with an SMI who are chained (see Figure 10.3), neglected or not well looked after. This means that every encounter you have is an opportunity to screen for mental disorder. For the most part, assessing for the presence of mental disorders is not too difficult and your skills will improve with experience.

10.1.1 The severity of mental illnesses

Mental illnesses are often classified according to their severity, which is estimated in terms of:

- the distress the symptoms of the illness cause

- the impact the symptoms have on the individual’s behaviour

- whether the symptoms affect the day to day functioning of the individual

- whether the symptoms also have broader effects on the family and society.

The majority of mental health disorders cause some level of distress to the individual concerned, but they have limited broader effects on the person’s day-to-day life, work, family or society. But about 5% of the population (1 in 20 individuals) have conditions that affect or interfere with their life seriously. Of those with a mental illness, almost one-third (3 in 10) are severely affected — in other words they have an SMI.

10.1.2 Priority mental health disorders

Severe mental illnesses, such as psychosis, depression, epilepsy and disorders that are common in children and elderly people, are collectively referred to as priority mental health disorders (Box 10.1) by the World Health Organization (WHO). The eight conditions listed in Box 10.1 require special focus from the health service, not only because they cause a lot of suffering to individuals, but also because they are treatable or can be modified through treatment. You will learn about them all, either in this study session or in a later one.

Box 10.1 Priority mental health disorders (WHO)

- Psychosis: this is the collective name for a group of serious disorders characterised by changes in behaviour (for example poor self-care, restlessness), strange thoughts or beliefs (for example believing that others wish to do the individual harm) and related dispositions. Psychosis is covered in Study Session 13.

Mania: a form of severe mental illness in which a person is excessively happy or irritable (experiences extreme mood swings), appears over-active and sleeps poorly. People with mania have poor reasoning skills (they have difficulty understanding what is good and what is bad), and display excessive self-confidence. Mania is covered in Study Session 13.

Mania is included under psychosis in the WHO list. The two are separated here for clarity.

- Depression: this is the most common priority disorder and is characterised by excessive sadness, loss of interest, lack of energy and related symptoms. It is covered in Study Session 12.

- Suicide: this will be discussed in more detail in this session and refers to the intentional ending of one’s own life.

- Abuse of alcohol and other substances: this is covered in Study Session 14 and refers to excessive use of these substances to the detriment of one’s health.

- Childhood mental disorders: these are covered in Study Session 17.

- Dementia: this condition is more common in older people and is characterised by memory problems and broader problems with thinking and understanding. Dementia will be discussed in Study Session 15.

- Epilepsy: this is a chronic or longstanding condition caused by abnormal electrical conductions in the brain. In its most obvious form, it is characterised by episodic loss of consciousness and repetitive jerky movements of the body. The various forms of epilepsy are described in Study Session 15.

Methods of assessment for all the conditions listed in Box 10.1 are detailed in their respective study sessions and some general assessment principles are provided in Study Session 11.

10.2 When to suspect a mental health problem

All encounters with people in your community should be taken as an opportunity to assess for the presence of a possible mental disorder. Usually a brief conversation during your house-to-house visits should give you some clue as to whether there might be a problem with mental illness.

In many cases, you will find that there are social factors that are causing the person distress, such as conflict within the family, problems with neighbours, loss (e.g. someone dying), unemployment or financial difficulties. Some people will have experienced serious problems while growing up. Others will be affected by a chronic medical condition or chronic pain that leaves them in a state of constant stress. In a very few cases, you may also find that there is a history of mental disorder in the family.

When circumstances like those described above are present, it is legitimate to suspect a mental disorder. For example, when someone comes to you complaining of persistent headaches, backache and/or abdominal discomfort, and medical investigations have eliminated any physical cause of the problems, you should consider the possibility that these might be symptoms of a mental disorder. A mental disorder is particularly likely when these complaints are combined with difficult social circumstances.

10.3 Common symptoms of severe mental illness

As the name indicates, a person with SMI has a severe illness that interferes with their life in a substantial way. Only a small proportion of those with mental disorder have an SMI. The symptoms and features of SMI are described in Box 10.2.

Box 10.2 Common symptoms of a person with SMI

- Delusions: believing things that are untrue, for example that people are in love with them, or that people are trying to poison them

- Hallucinations: hearing or seeing things that no one else can hear or see

- Agitation and restlessness

- Withdrawal and lack of interest

- Increased speed of talking

- Irritable mood (getting angry easily)

- Grand ideas (out of keeping with reality)

- Talking in a way that does not seem to make sense

- Poor self-care (not related to poverty).

When you find two or more of the symptoms listed in Box 10.2, an SMI is likely. However, you need to retain an open mind because it is also the case that, when these symptoms occur acutely, i.e. they arose all of a sudden and have been present for less than a week, these same symptoms could be due to another serious medical condition such as malaria, meningitis or pneumonia. Alternatively, when these symptoms are exhibited by a person who drinks a lot of alcohol, they could also be due to changes in the brain caused by drinking. Therefore, it is very important that your assessment is thorough and that you do not confuse physical illness and mental illness in identifying the underlying causes of severe symptoms. The failure to detect and treat malaria, meningitis or pneumonia quickly could result in the patient dying within hours or days.

10.3.1 What to look out for in a person with SMI

This is very similar to what you do when you meet someone you have not seen for a long time. You are curious and you want to find out what has changed in that person over the years. You notice the way they approach you, whether they look interested in you, how they are dressed and how they appear more generally (whether they have taken good care of themselves, whether they have lost or put on weight, etc.), whether they seem kind or careless and so on. Similarly, it is important to be natural and have some curiosity when you see someone whom you suspect to have a mental illness. The main difference is that you try to be more systematic in your approach when you see someone with a potential mental illness. The following guidelines will help you to do this.

Appearance

How does the person appear? Are they calm and dressed appropriately? Are they as clean and tidy as you would expect them to be? Do their actions seem restless and agitated or, the opposite, tired and seemingly slowed down? Do they look physically sick? Do they behave aggressively? Do they appear suspicious of you or others? Do they look at you openly or do they look down or away all of the time, avoiding eye contact? Do they seem to talk or laugh to themselves for no obvious reason?

Speech

Does the person speak at all? Can you make sense of what they say, and how easy is it to understand what they are saying? Do they speak too loudly or too quietly, or does the volume of their voice seem normal?

Emotion

Does the person appear or act in a way that is unusually or inappropriately over-cheerful (too happy), or do they seem very sad for no clear reason? Do they behave in a fearful or aggressive manner?

Thinking

Listen carefully to the content of what people say, because this provides a clue to how they are thinking. What does the person worry about? How much do they worry? Are these worries common to most people, or do they seem extreme or at odds with reality?

Perception

This refers to the person’s ability to connect with the outside world through their sensory organs (eyes, ears, etc.). You should attend carefully to find out whether the patient’s hearing, sight, smell, taste, touch and/or other sensations have been affected. When a person perceives things that are not really happening this is usually called a hallucination (look back at Box 10.2). Ask the person and/or their family if he or she sees or experiences things that might indicate they are having hallucinations.

Insight

This refers to whether the person is aware that they have a problem. For example, the man who fears his wife is being unfaithful may believe this is true, even when the evidence strongly contradicts him. In such circumstances he is likely to be unaware that what he thinks about his wife is a symptom of his mental illness: he lacks insight.

There are many more abnormalities a person with mental illness may have, but most people with SMI tend to have one or more of those listed above. You will learn more about what you should do when you suspect someone has a mental illness in Study Session 11. Mental illnesses are not without risk. We will now first discuss how you can manage the risks associated with mental illness.

10.4 Assessing the general risks from mental illness

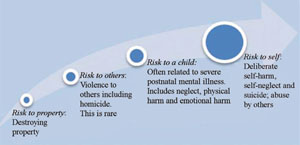

Concerns about risk in relation to mental illness relates to the management of potential harm. Here ‘harm’ has several distinct meanings, depending on the form it takes and at whom it is directed. There are three broad categories of risk: risk to self, risk to others and risk to property. Hence, risk management means thinking about the harm posed to the mentally ill person as a direct or indirect result of their mental illness (including self-inflicted injury and harm caused to the ill person by others), and about the harm that those with mental illnesses might pose to other people or property (Figure 10.4). These risks are more common in people with SMI, although they can occur with any form of mental illness.

It is important to realise that the fear of people with mental illness is far worse than the evidence suggests it should be. People with mental illness rarely pose a risk to others, although this is unfortunately not understood by many of the general public, who continue to hold irrational fears about people with mental illness. In fact, people with mental illnesses are far more likely to be attacked and abused by others than they are to behave aggressively or violently themselves. In Ethiopia, people with SMI tend to die from injury-related causes much more often than others in the general population. This is also reflected in the fact that the most common form of harm associated with mental illness is self-harm through neglect.

10.4.1 The main risks in mental illness

However, this does not mean that risks to others, though rare, should be dismissed from the mind altogether. For example, if a new mother experiences a severe mental disorder, such as acute postnatal depression, you must keep in mind the potential risk to the newborn baby. The mother may fail to look after or feed the baby as she would otherwise do (Figure 10.5) and, without the support of others (including yourself), the baby could be at risk of neglect. In the most extreme (and rarest) of cases, the mother may also harm or even kill her baby. When a mother has such severe symptoms of mental illness, you should try to locate other family members or close friends who can offer the mother support by taking on some caring responsibilities for the baby.

The main risks arising from mental illness are summarised in Table 10.1, together with a brief indication of how you would assess them. You will learn about risk assessment in more detail in Study Session 11.

| Risk | Risk assessment |

|---|---|

| Risk of suicide | Any mental disorder increases risk of suicide. Ask gently but directly about it (see Study Session 18). |

| Risk of self-neglect | In this case, the person may not eat and drink enough or dress appropriately, wander the streets disregarding the weather, sleep rough and so on (see Figure 10.6). Such self-neglect is more common with severe mental disorders. You can ask the family or the patient directly if they are eating enough and/or looking after themselves. |

| Risk of violence | Very uncommon. Ask what triggers the violence and explore past history. If there is a past history of violence, or if violence occurs for no obvious reason, this increases the risk of further violent behaviour in the future. Also check if incidents of violence have been related to the misuse of substances such as alcohol or khat. Addressing this misuse may substantially reduce the risk posed. |

| Risk to children and other dependents | If children or other dependents (for example elderly or sick people) are living in a house alongside someone with serious mental illness, ask how they find living with this person. Specifically, ask if there are frequent conflicts, any assaults or times when they feel particularly threatened; try to involve the neighbours in answering these questions. If you find there is a risk to children or other dependents, ask what is being done to address it. Make sure the person is receiving the appropriate treatment. |

| Risk of abuse | Commonly, persons with SMI are likely to be the victims of abuse or violence. Many are stigmatised, insulted and even physically abused because of their condition. This risk is primarily tackled by educating the community about mental health issues. |

10.5 Assessing the risk of suicide and self-harm

Assessing the risk of suicide is perhaps the most important part of risk assessment. Suicide is an act that cannot be reversed. You cannot do anything for the person once they are dead. The main strategies for suicide, therefore, emphasise effective prevention by identifying and treating people early when they are at risk of committing suicide.

The need to assess the risk arises in two situations:

- when someone has indications of significant mental illness, such as depression or alcohol abuse

- after someone has tried to end their life in the past.

In both these situations, there are some common risk indicators, for example being jobless, of lower educational status and being in either a younger or an older age group. These are discussed in more detail in Study Session 18. The risk of suicide has to be considered to some extent in all cases of mental illness, particularly those priority conditions listed in Box 10.1. The main risk indicators for someone with mental illness are shown in Box. 10.3.

Box 10.3 Suicide risk indicators in people with mental illness

- Suicidal thoughts: if a person tells you they are thinking about suicide, you should take this very seriously; about 66% of those who commit suicide have previously told someone about their intention.

- Severity of mental illness: the more severe the illness, the higher the risk of suicide. Someone young with a severe mental illness like psychosis, may be at increased risk if they have developed awareness about how ill they are; this is particularly the case if they also develop depressive symptoms (Study Session 12).

- Substance misuse: the risk increases when the person also misuses substances like alcohol and khat.

- Social isolation and lack of support: for example, when someone does not have family to care for them, is single, and/or jobless. Marriage reinforced by children is thought to be a protective factor in relation to the risk of suicide.

History of suicide attempts or self-harm: the risk is increased if there have been previous attempts.

The terms ‘self-harm’ and ‘suicide attempt’ are used here interchangeably.

When someone has already attempted suicide, their risk of suicide is about 100 times higher than that in the general population. This risk is particularly high in the first year after the original attempt. It is therefore crucial that you closely monitor the risk of suicide after an attempt has been made. Be open with the patient, asking about the risk as a matter of fact.

Most people who self-harm do not intend to kill themselves or end their life. In low-income countries like Ethiopia, many die even when they don’t intend to do so. This is because the methods they use to self-harm are dangerous. For example, certain poisons, such as pesticides used by farmers, are fatal if swallowed unless the person gets immediate medical help – which is not available in most rural communities.

In Ethiopia, up to 20% of individuals self-harming may end up dying. This figure is about 1% in high-income countries. It is therefore important to identify people who self-harm. Box 10.4 lists some factors that indicate a risk for serious self-harm. Establishing the intent of the person when they self-harmed (whether they were intending to die, or self-harming to indicate their mental distress), gives you a good clue about future risk. If there are indicators of a serious intent to end their life, the risk of successful suicide in the future is high.

Box 10.4 Risk indicators for life-threatening self-harm

- Preparation for self-harm: someone who has taken time to plan, considered the consequences of their actions, said goodbye to people or taken precautions to avoid being discovered by others represents a much higher risk than a person who self-harms without much thinking about it (i.e. self-harm as an ‘impulsive’ act).

- Seriousness of the method used to self-harm: violent methods such as hanging, stabbing or throwing oneself into deep water are considered serious and indicate higher risk.

- Current mental illness: at least 60% of people who self-harm have some form of mental illness.

- Factors that reduce self-control: the use of alcohol or other drugs, or having an impulsive personality, reduce self-control and increase the risk of serious self-harm.

- Presence of ongoing ‘real life’ difficulties: marital problems, financial problems, difficulties at work, or other problems in daily life increase the risk of self-harm.

Note that the factors described in Box 10.3 are also important.

10.5.1 Questions to ask someone who has self-harmed

You need to be both sensitive and direct when you ask about suicide. Suicide is a difficult or ‘taboo’ issue which many people find difficult to talk about, particularly in public. You should talk to the person alone and question them gently. If you are talking to the person after they have just attempted suicide, they are likely to be feeling a range of powerful emotions, including shame and despair. Other people may make these feelings worse by criticising them for being cruel and/or selfish. It is important that you counteract this. Tell the person that things must have been tough for them to try to end their life. After listening carefully to their response, you can proceed to ask them direct questions about the suicide attempt. Asking about suicide does not increase the risk of suicide. In fact, some people feel relieved they are being asked.

Activity 10.1 Posing questions based on the self-harm risk indicators

Read the risk indicators for self-harm in Box 10.4 once again. Then write down some appropriate questions to ask a person who has self-harmed, based on each of the five indicators highlighted in the bullet points. Then compare your questions with our suggestions below.

Answer

You may have suggested equally good (or better) questions than those below:

Preparation: What triggered this action? How long did it take you to attempt it from the time you actually thought about it? Did you worry that people might find out? Did you say goodbye to your loved ones?

Method: At this stage you would know what method they used but you would not necessarily know the details. Ask about these details. If you did not know the method, you should also ask: what did you use to injure yourself? You can then ask if they required treatment for the injury, and if so, what it was. You may also ask if the person has ever done something similar in the past. This assesses the history of self-harm (see Box 10.3).

Current mental illness: Has anyone ever discussed the possibility that you might have a mental health problem?

Factors causing loss of control: Were you drinking alcohol or chewing khat before you tried to injure yourself?

Ongoing difficulties: Are there stresses or difficulties in your life, for example, problems at home or not having enough money?

Additionally, ask them about their intention when they self-harmed. You can, for example, ask: What did you hope would happen when you cut yourself with a knife? Now that you have survived, what do you think about what you did? Are you relieved that you did not die? If the person tells you that they are disappointed that they survived, this indicates a continuing high risk.

Study Session 18 (Section 18.4) includes practical advice on how to reduce the risk of suicide.

10.5.2 Asking about possible suicide when someone has a mental illness

As stated earlier, suicide and self-harm are significant risks in people with SMIs. In order to investigate the risk in an individual patient, you should gently ask about their view of the future, their sense of self-worth and, when your relationship of trust is well established, whether they experience upsetting or persistent thoughts about death, including possible suicide. Examples of questions you can use to help investigate these difficult issues are provided in Box 10.5.

Box 10.5 Questions to help assess the risk of suicide in someone with a mental illness

- How do you see the future?

- Do you think things will get better for you?

- Are there times when you feel you have had enough of life itself?

- Are there times when you wish you were dead, or when you feel it would be better if you had died?

- I know this may be a difficult question, but have you even considered ending your own life?

- If you have thought of suicide, have you thought how you might do it?

If the person answers yes to any of the last three questions, you must refer them to a higher health facility for further assessment.

In this study session you have learned some important principles of mental health assessments, especially about the risks associated with mental illness. In the next study session we continue the theme of mental health assessment more generally.

Summary of Study Session 10

In Study Session 10, you have learned that:

- People with severe mental illness (SMI) pose more of a threat to themselves, through neglect and self-harm, than they are a risk to others; and they may be at significant risk of abuse by others.

- The WHO priority mental disorders identified as treatable or capable of being modified by treatment are psychosis and mania, depression, suicide, substance abuse, childhood mental disorders, dementia and epilepsy.

- The main purpose of your discussions with a person with a possible or actual mental illness is to understand their problems and to assess the risk they may pose to themselves or to others.

- When talking to a person with a possible SMI, pay attention to their appearance, speech, emotions, thinking, perception and insight, and their intentions if they have self-harmed.

- Careful and sensitive questioning can help to screen a person for the possible signs of mental illness and assess the risks of self-harm or suicide.

- The risk indicators for repeated self-harm include making preparations for suicide, previous attempts, using a violent method, substance abuse, and presence of ongoing difficulties in their life.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 10

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of the Module.

First read Case Study 10.1 and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 10.1 Mrs Chaltu’s story

Mrs Chaltu is a 30-year-old woman living on the outskirts of Adama city. She went to Adama when she was 20 after a hasty marriage to a man she had known only briefly. The family were not happy with the marriage, believing that a longer engagement would have been more appropriate. Lacking support from the family, the marriage has proven difficult and her husband has struggled to sustain paid employment. Mrs Chaltu has become more worried about her life and future in general. They do not have any children and this is a source of sadness to Mrs Chaltu.

Recently, her elder sister – whom she loves very much – told her she was going to visit. They had not seen each other for two years because they live far away from each other, the bus journey takes several hours. Mrs Chaltu was very excited about seeing her sister, but when she was preparing the house before going to the bus station, she received a phone call from her sister saying she could not come because of some personal difficulties. Chaltu was so upset by this that she picked up the berekina (chlorinated bleaching liquid) she was using to clean the house and began drinking it. Chaltu was found by her husband before she had drunk very much of the liquid, and she received prompt medical treatment which saved her life.

SAQ 10.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1, 10.2 and 10.3)

Describe the main symptoms that Mrs Chaltu presents with and identify to which priority mental health disorder(s) they are likely to relate.

Answer

Mrs Chaltu seems unhappy and sad, and worried about her life and her future. Her sadness could be an indication of depression. Depression is a priority mental health disorder. After her sister could unexpectedly not visit her, Mrs Chaltu tried to end her own life by drinking Berekina. Suicide is also included in the list of priority disorders.

SAQ 10.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.4 and 10.5)

What more do you need to know about Mrs Chaltu before you can assess the level of suicide risk more accurately? Describe some of the questions you would ask Mrs Chaltu to try to assess the level of future risk of self-harm or suicide.

Answer

There are several aspects that you need to know more about before you can assess the level of suicide risk more accurately:

- You need to know more about the incident of self-harm. It seems that it was not a pre-planned suicide attempt, but you need to establish whether the Berekina drinking was a serious attempt at suicide and how she feels about this now. To understand more about this, you could ask questions such as: ‘what did you think would happen when you drank Berekina?’ ‘How much of it did you take?’ ‘Did you believe the amount you took would kill you?’

- You need to find out if there is any past history of self-harm. If she has such a history, the risk of future suicide is greater. You can assess this by asking questions such as: ‘Have you ever tried to harm yourself before?’

- You need to know more about whether Mrs Chaltu has suicidal thoughts more often. You can assess this by asking general questions about how she sees the future, and more direct questions such as, ‘Are there times when you wish you were dead?’(See also Box 10.5).

- You need more details about Mrs Chaltu’s social circumstances. It appears that Mrs Chaltu has some social problems, including family problems and financial worries. You can get to understand Mrs Chaltu’s situation better by asking her questions like: ‘Are there things in life that you worry about?’ ‘Do you have enough support from family and friends?’